Benjamin Lignel is curator of Also Known As Jewellery*, an exhibition of French contemporary jewelry that has been traveling the world. AJF asked him some questions about the exhibition and the work featured in it.

Damian Skinner: What is Also Known As Jewellery*?

Where has it traveled?

Benjamin Lignel: The exhibition was launched in March 2009, at Flow in London and was then hosted by Alternatives in Rome and Velvet da Vinci in San Francisco. Our last host will be Idar-Oberstein’s Villa-Bengel, where the show will spend the summer, after a brief but most exciting stop at the Institut Francais of Munich, where it is currently presented to coincide with the famed Handwerksmesse in March.

To show in such different places – different both in terms of gallery set-up and audience – almost means doing five different shows: for even if the pieces had remained the same throughout (they did not), the exhibition itself would have been re-configured to suit each gallery and re-modeled – as it were – by the very contrasted expectations of each population of visitors.

Benjamin Lignel: I suggested the idea for a ‘French’ show to Yvonna Demczynska, the owner of Flow gallery, during the vernissage of an Italian show she hosted in 2008. No one participating in the conversation could remember seeing a French show: in fact, very few knew the work of more than a couple of French jewelers. This in turn determined the dual agenda of the project: give French jewelers as much exposure abroad as possible and provide visitors with a comprehensive critical tool to access their work. Hence the long tour on the one hand and the catalog on the other.

The original plan also included a French stopover, for our French contemporaries are painfully ignorant of the fact that such a thing as contemporary jewelry exists. (There are exceptions – you know who you are!) Things are improving slightly, but there is quite some way to go. This has not yet materialized and may prove to be the one big frustration of the project.

Why did you think it was important to undertake this project?

How did you select the jewelers for the exhibition? The writers for the catalog?

As said before, producing a catalog was fundamental to the project. We wanted to provide visitors (or readers) with multi-layered information about each artist and chose an editorial approach that favored individual practice over a group study. In effect, the catalog is made up of seventeen folded and rubber-bound posters. It can be read as you would a book, by leafing through the pages in sequence, or taken apart and enjoyed as a set of posters.

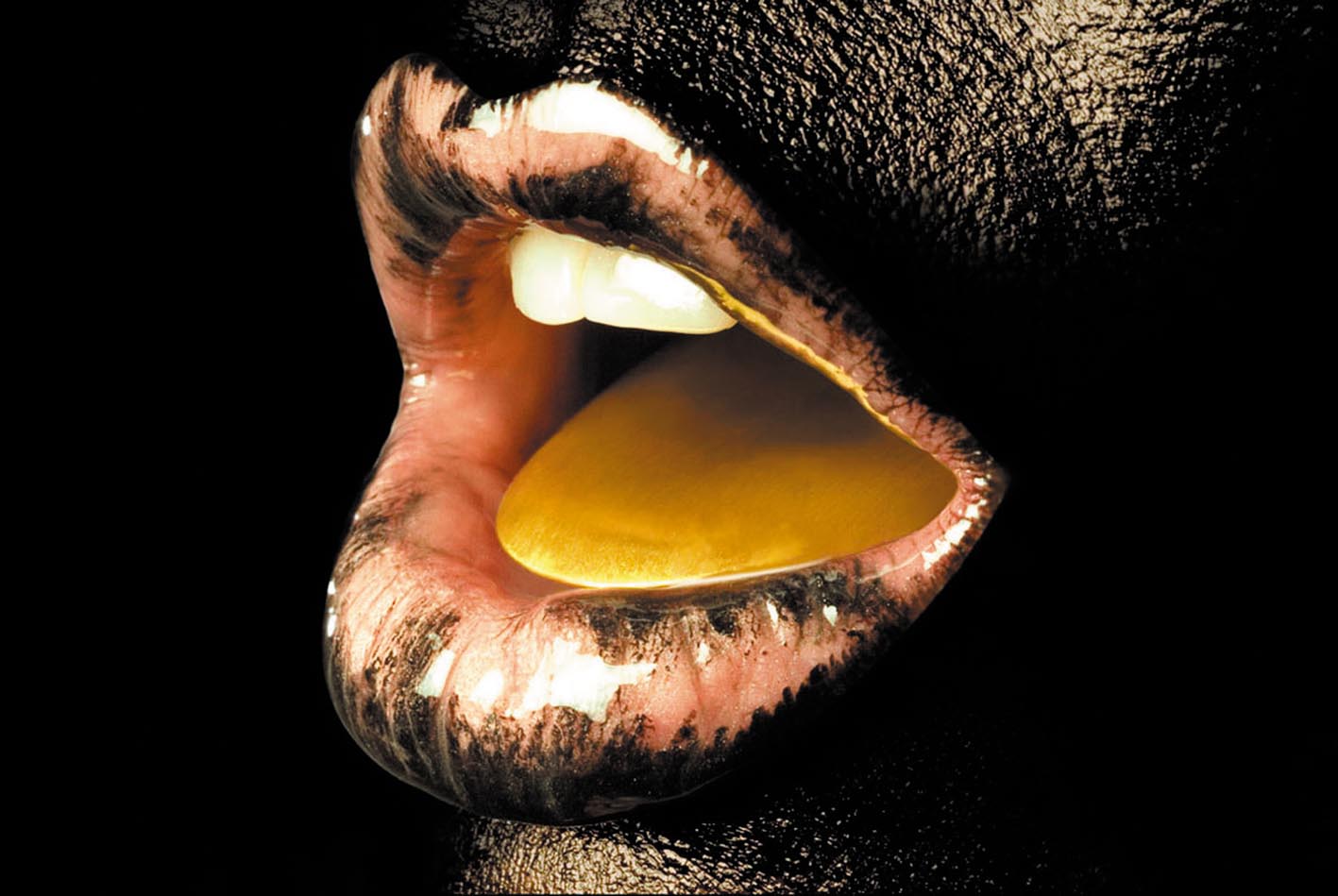

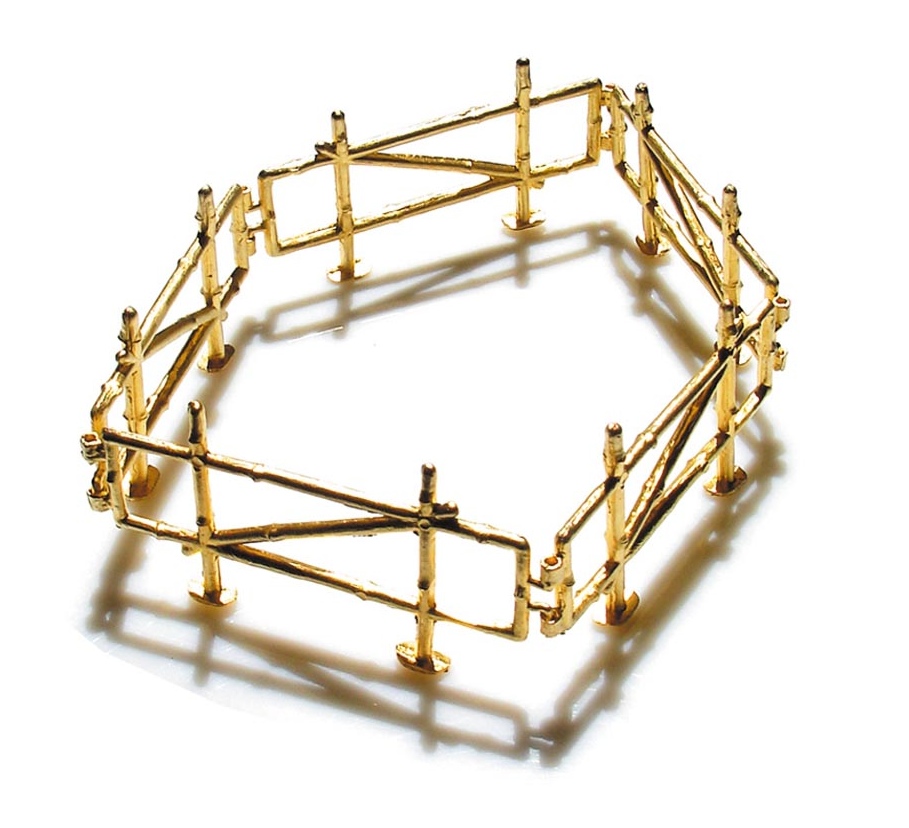

Each poster is treated as a self-standing publication, featuring a series of studio pictures shot specially for the catalog (and, in some cases, pictures of older work for added background) a portrait of the individual artists wearing one of their pieces, a short CV and a 500-words essay written for the publication. Makers were offered the possibility of suggesting a writer (some did) but in most cases they were ‘matched’ with writers we felt would do their work justice, chosen from a wide range of disciplines: poet, artist, sociologist, philosopher, historian, anthropologist, gallery owner, curator. While looking for seventeen writers, coming at them with the bargaining power of two beggars on the dole, we found, surprisingly, that a lack of institutional interest for jewelry whetted the appetite of researchers. It afforded them a sort of intellectual terra incognita with more than circumstantial relevance to their ‘legitimate’ areas of research. Only two people turned us down out of nineteen who were approached.

Benjamin Lignel: I don’t think it makes one argument about contemporary jewelry in France; it makes seventeen of them – each one with its own history and very individual ways to relate to the larger phenomenon of international contemporary jewelry. (They had been starved, now they want food.)

Do you think that nationality is a very useful way to think about contemporary jewelry? What is French about French contemporary jewelry?

If there is such a thing as heritage, or lineage, I would argue that its strands are best seen in the tutor/student relationship. Contemporary jewelry is unusual (compared to design, say, or the fine arts) as long teaching tenures on the one hand and a relative scarcity of schools on the other have allowed teachers to thrive and their varied influence on students to be both quite visible and visible over time. Brune Boyer and Sophie Hanagarth in France, OttoKünzli in Germany, Caroline Broadhead in England are good examples of a ‘background’ that informs the way students approach the trade, and allows them to bloom.

Has the exhibition been successful?

Benjamin Lignel: Contrary to popular wisdom, I believe that translation is invigorating for any work of art – showing work coming from place A in place B and finding how relocation has affected its capacity to inspire. From that point of view, the show’s success has been spectacular, as it engaged – and was commented on by – three very different crowds at its openings. A very academic crowd in London, necessarily well equipped to ‘get’ the show as a whole and to relate to individual pieces; they were kind enough to acknowledge that French jewelry did, in fact, exist, bless them. In Rome, a mix of regular clients and uninitiated guests, who found themselves irked and excited in almost equal measures by conceptual propositions that are quite alien to the subtle material poems and technical pyrotechnics that are the hallmark of the Padua school. A roster of militant collectors and jewelry lovers in San Francisco, very sympathetic to the agendas of some of the makers (gender, corporeal identity) and quite committed to saying so.