Now in his fiftieth year as a jeweler artist-designer, Goph Albitz has traversed a range of aesthetics, from clean and precise jewelry informed by his background in precision machining to his more recent organic jewelry, which is reminiscent of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon. In this interview, we talk about his holistic approach to creating the one-of-a-kind jewelry that is featured at J. Cotter Gallery in Colorado.

Olivia Shih: Could you talk a bit about your education and eventual path to becoming a jewelry artist?

Goph Albitz: I served a five-year apprenticeship as a toolmaker in the aerospace industry in Santa Monica, then two more years as a journeyman toolmaker. At that time, I studied industrial design at Santa Monica Community College and took some classes in architecture at El Camino College.

Later on, and to date, I continue to take workshops by professionals when I need to learn a skill for a project in mind. On the other side of that I have taught some workshops and taught a lapidary class at Monterey Peninsula College.

What is it about jewelry making that draws you in and excites you?

Goph Albitz: With sculpture, I create my concept in three dimension and in metal—an idea of colors, balance, something that portrays a feeling and overall beauty. In jewelry, the thing that is even more exciting is that it is on such a small scale and is made with precious and semiprecious stones, gold, and other fine metals. Plus you can wear it.

What might a day in the studio be like for you?

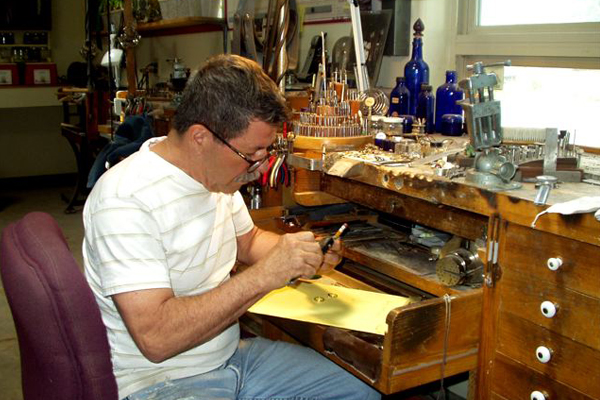

Goph Albitz: A day starts about 6:00, 6:30. I stroll down the path on our 10 acres to the studio. The only traffic is rabbits, deer, and an occasional owl sitting in a tree. Then to my espresso bar for coffee, with maybe a bit of dark chocolate. Then I fire up the studio (2,000 square feet) by lighting the wood stove, turning on pickle pots, and checking the Internet for any news coming in and my fans on FB. Post new work, then go over what I was working on the day before or start some sketches of what I will begin today.

Then comes the journey back to the house; by now my wife, Lorry, is up, and I have breakfast and coffee with her. Then I begin making the pieces of the day. After 48 years of doing this, it is still exciting every new day because the possibilities are endless.

Where do you live now, and does your environment seep into your jewelry work? Your current work, with its asymmetrical and organic lines, reminds me of Big Sur, where you spent some time in the 60s and 70s.

Goph Albitz: I’ve lived in Bend, Oregon, since 1998. My studio looks out on the Cascade Mountains and my beautiful garden, both of which take me back to a similar environment as I had in Big Sur. I’ve included pictures.

I find inspiration from nature in general, and the natural osmosis or evolution of organic matter, but also the breakdown of the industrial, as in “Retro-Industrial.” I love the look and textures of raw concrete or rusted steel and rotted wood, and chipped eroded layers of paint.

Here in Bend (in central Oregon), we are surrounded by black lava flows, and I love the contrast of the rough texture of the lava against the bright greens and colors of the flora.

The cracks in my work are stress cracks created by overworking the metal until it hardens and starts to come apart. This becomes the center of the design. Like our lives, some of our character and focal points come from what we take or learn from the flaws, mistakes, and stressful events.

You’re an artist who at one time showcased jewelry in more than 50 galleries and department stores but ultimately chose to cut back to a three-person studio. What led you to this decision? What were the trade-offs?

Goph Albitz: Showcasing in the 80s to now: To point out here and not to mislead, I was in 50 stores and galleries, but 20 of those were combinations of department stores—12 Nordstroms, three Neiman Marcus, and five Saks.

I wouldn’t characterize it as a trade-off, but more like returning to my original goals! I got caught up (as so many do) in becoming BIG, getting rich and famous, and I lost the joy of being an artist; I no longer actually made anything. I was a director of a staff of jewelers making what sold and not what I wanted to create each morning.

So now I have cut back to solely ME. I conceive and make each one-of-a-kind piece from start to finish, i.e. alloying the metal, pouring the ingots, fabricating and texturing the metal, fusing the gold, setting the stones, and doing a final polish. Now I am in 10 fine galleries and do three international art and jewelry shows, and I’m represented by Oliver & Espig of Montecito, California. The showcases allow me a market that appreciates and can afford my finer work, thus fulfilling my goals to create my ideas.

In 1980, you created a series called Stacking Rings, in which you created stackable rings with gemstone inlays. What led you to do this design? Any thoughts on the current stackable rings trend?

Goph Albitz: In the 70s there was a popular jewelry book out, I think it was titled Modern Jewelry, maybe? On the cover was the work of Wendy Ramshaw. She did a collection of rings that fit on a stand as a sculpture and that you wore all together. I liked the idea of many making one, so I came up with my version of inlaid stone rings in multiple colors that you could pick and arrange in your own style of a stack of rings. Collecting many colors, one could then pick a color combo to go with the day’s apparel. So though I didn’t invent the concept, I did pioneer my version of the stacking rings, now made by so many.

Could you name three emerging jewelry artists whose work excites you?

Goph Albitz:

Valerie Ostenak (though not emerging) combines forged steel, gold, and pearls.

Marcos Rosemberg from Brazil makes amazing sea fantasy jewelry.

Greg Franke of “Alex and Lee” (also not emerging), but he makes such unique fiber and stones jewelry.

Finally, Birgit Kupke-Peyla.

Have you seen, heard, or read anything interesting that you would like to share?

Goph Albitz: A wonderful book by Hans Silvester, Immortal Angels, features years of photos of the natives of the Omo River region in Ethiopia.

Thank you.

The price range for the work in this exhibition is $900 to $8,500.