Body Alchemy

November 7–19, 2015

China Academy of Art’s Contemporary Art Museum, Hangzhou, China

It started with an egg, I was told, as many things do. All things have to start somewhere, and finding just the right departure point when organizing a cross-cultural exhibition of over 80 international artists is a crucial first step. The theme, Body Alchemy, though rather fitting with curator Ruudt Peters—who has circled back, both as curator and artist, to this subject and has spent extensive time in China doing research—was actually chosen by the show’s host institution. The 35 Chinese artists included were picked from an initial larger list provided by co-curator Zhou Wu, the dean of the College of Crafts at China Academy of Art (CAA), from which Peters made final selections. And the 51 remaining artists who fulfilled the western counterpart of the exhibition (plus their specific pieces) were picked by Peters with free reign. So somewhere in the Internet space hovering between the Netherlands and China, this exhibition was organized in virtual cooperation. The timeline from conception to debut: three short months. Exhibition length: 12 days. Seminar length: two days. But the budget? B I G. Six figures big.

Body Alchemy, though not exactly a groundbreaking concept, was an appropriate choice to accommodate the many individual voices the show aspired to showcase. That’s mainly because it is an easy choice for a show consisting of contemporary jewelry (primarily) and hollowware: By nature, the work, in all its diversity, cannot turn its back on the body. The show’s title poetically admits this, but also risks seeming just a convenient umbrella under which to place a lot of different jewelry.

When investigating how the idea of “Body Alchemy” underscores a more Chinese sensibility and relationship to jewelry and art in general, easy starts to drift to apt. Chinese art is still arguably very much a national art, coming from a unique and specific cultural history that’s difficult to strip away. Whatever the vantage point, the theme ultimately does ask the viewer to re-acknowledge jewelry’s unique symbiosis with the body, and it reminds the artist and student alike to be appreciative of it, to not forget it. This is not a bad thing. It also kept even the most conceptual work on exhibition humble.

So back to the egg, or rather, Carrying Device for an Egg, by Sigurd Bronger (Norway). This was the first piece of jewelry Peters selected for the show, and the rest of the selection was built up from there. Were the chosen artists the best qualified to speak on behalf of jewelry’s bodily role? Out of all the work that makes up this world of contemporary jewelry, were these 200+ pieces our best and most diverse examples?

Many of the included pieces required the viewer to figure out how exactly they played with, or adhered to, the theme, in all of the infinite and subtle possibilities. I certainly found myself trying to crack some code of why certain work was there, or with what aim Peters called on particular pieces. Some work that at first seemed out of place came to make more sense with time and reflection. Wen Hsien Hsu’s (Taiwan) Between Series brooches—silk stitched cotton fabric rolled like measuring tape, used to determine the figurative distance between things like passion and apathy—are a good example; the work only begins to make sense after learning the artist’s full intentions. Some of the other work, meanwhile, seemed completely out of context: Norman Weber’s (Germany) gold brooches from the Bijou Series (2015) come to mind (though his Flocked Balls, 2014, did work), as do Benedict Fischer’s (Austria) bright-colored, large plastic brooches (2014). I recall being particularly baffled when I found Peter Skubic’s (Austria) Pedestals for an Invisible Ring (2015), made of colorfully painted cardboard—but we’ll let that one slide, given its charm.

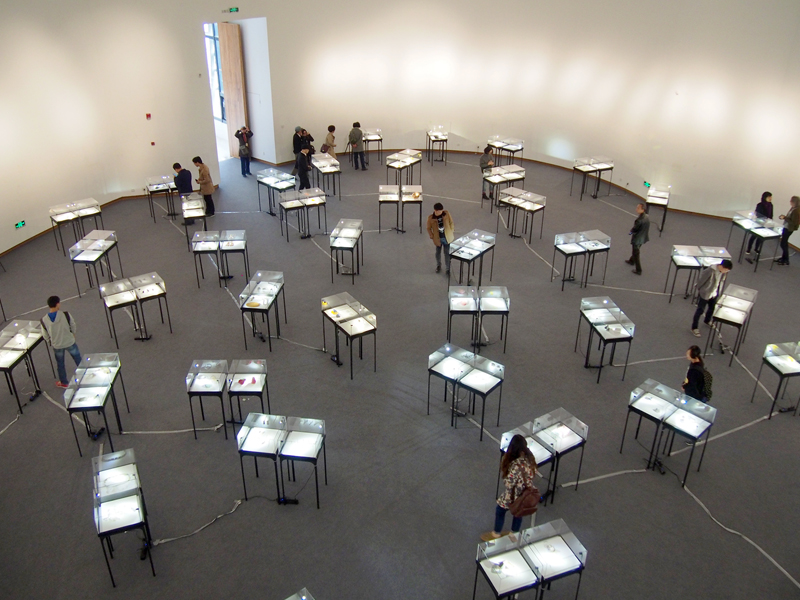

Some of the more formally sculptural jewelry struggled to speak loudly among other conceptual contributions; certain pieces from Estela Saez (Spain) and Annamaria Zanella (Italy), for example, felt too industrial to relate to the theme. At times, while walking around the two enormous oval-shaped spaces that housed the exhibition, I got the sense that the lineup of artists had to fulfill some kind of international prerequisite, that some selections were consequently checks off a set list of countries. Whether that was CAA’s or Peters’s striving for diversity, it was both good and bad, and for every downswing in this exhibition there was an upswing: While some of the inclusions felt like too much of a stretch, others may have mistakenly been left out otherwise. Carine Terreblanche (South Africa) comes to mind, whose carved jelutong wood pieces, Clues and Indie Pendant (2013), were a positive addition to the selection, and work I’ve never seen before.

Finding pieces that truly fit the theme’s bill took some time but wasn’t difficult. Christoph Zellweger (Switzerland), who often speaks about the natural versus cultured body and the blurred line between, had some of the more literal successes in the show. His leather works from the Hip Piece series (2002)—which welcomed the visitor into the first room—and his transparent blown-glass blobs from the series Excess (2012) were perfect anchors for the exhibition. More symbolic examples came from Ted Noten (Netherlands) with objects ranging in materials from the series Crosses from Tokyo to Moscow (2015). Although placed far apart and not visually similar, I found them to be a nice complement to Guo Xin’s (China) filigree and clay Metamorphosis pendants, which reflect the meditative qualities of jewelry and speak about sincerity.

Although it could be of value in this text to continue to describe other successful pieces similarly, it just can’t happen. There’s too much work, and yet another code to crack: Each piece was paired with another, placed in binary display cases. More often than not, an Asian artist was paired with a non-Asian artist. A dialogue was meant to be created between each pairing, between East and West, Peters told me, and the pairings were sometimes laborious, sometimes serendipitous. Trying to discover the relationship between the pieces—whether it was more formal, conceptual, or emotional—was often fun.

There were hits and some real misses. The sign of a good match is when both entities are lifted up via their association to one another. Ke Zhen Wang’s (China) impressive silver Bone Artifacts (2008) were the perfect visual consequence to Aaron Decker’s (United States) Tank (2014), a brooch that is part of a series that includes Debris and Bomb. Lucy Sarneel’s (Netherlands) Grey Beady brooch (2013) gave Donghyun Kim’s (Korea) tin-plated copper vessel, Rising (2012), the contemporary twist it deserved; his immaculate craftsmanship was luscious and overwhelming in all of his pieces.

A surprising but solid pairing: Christiane Förster’s (Germany) lightly enameled silver pieces (2015), delicate like fragile folded paper, were not particularly interesting or relevant to the show until I saw one next to Xiao Liang’s (China) work. His intestinal stuffed-silk brooches, dusted with colored growths, similarly came alive through the association. The rest of the pieces of both artists then earned another look—especially Liang’s. His Incessantly Chatter series (2015), in particular, turned out to be one of the most curious and fresh inclusions in the whole exhibition.

Having the right lens with which to look through is a vital component of good exhibition making. Because the lack of context and stark environment did nothing for the many works, the pieces were even more reliant on the right pairing, like in the last examples, to be seen and understood. Unfortunately this didn’t happen every time and some good work consequently suffered: Although beautiful, Tore Svensson’s (Sweden) giant raised iron bowls (2013) did nothing for Jing He’s (China) Potential Pins 1-3 (2014), for example. Which is a pity: Jing’s work is super-relevant and refreshing in the world of contemporary jewelry, not to mention some of the smartest work in the room. There were just too many pairs.

Big shows are often bad or boring shows because they lack vision, appearing as a survey of Contemporary Jewelry 101, and at times feel like work, with so many individual pieces that deserve attention. Going in initially I was afraid of this. An overriding question when visiting the show was indeed why Peters would associate his name to such a formless curatorial project in comparison to what he is known for. His far more complex past curatorial endeavors, like Lingam, or any number of his own exhibitions for that matter, usually take every last detail into account while utilizing some relatively innovative display mechanism. Some of the things that were skimped (missing labels, bad carpet, banal display cases, etc.) probably fell through the cracks of time constraints, co-organization, and compromise. I do know that Peters had other ideas in mind for what the jewelry should be displayed on, but a bunch of Plexi boxes he got instead. Did this setup manage to communicate a basic understanding or appreciation of all the pieces, or lend them a collective meaning regardless? I can’t say I know, and perhaps it is a moot point anyway, considering there are hardly any alternatives when it comes to displaying that many individual works securely.

But let’s ignore all that; there are bigger fish to fry. The show’s real purpose goes far beyond examining “the spiritual chemistry between body and jewelry,” as Peters says the show does. The money for this expensive project was spent elsewhere; many of its international artists were flown in to attend the opening—as I was—and with that came a costly seminar. The speakers: Carin Reinders, director of CODA Museum (Netherlands); Liesbeth den Besten (Netherlands), historian and writer; Guo Xin (China), head of the jewelry and metals studio in the College of Fine Arts at Shanghai University; Zheng Hong Wang (China), head of the jewelry studio at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou; Fan Zhang (China), artist; David Huycke (Belgium) artist; Tanel Veenre, artist (Estonia); Tarja Tuupanen, artist (Finland); and Christoph Zellweger.

If Body Alchemy worked as a title for the exhibition, it was more confusing for the seminar, as was the program itself: a combination of traditional artists talks, museum introductions, a random-seeming video by Hilde De Decker (Belgium) and a talk from Peters about his own work—and not the show—that left me puzzled as to what the takeaway should be, or the point of it all. Finding common ground? Sharing cultural tendencies? Establishing universal values in jewelry? The contributions from the West tended to be convoluted, not to say self-centered. In contrast, the Chinese contributions by Xin, Fang, and Wang felt they were more about sharing and broadening their own perspectives and that of others: They were quite enlightening, providing a real window through which to see and better understand jewelry from a scene we still know very little about. It was only during the post-presentation Q&A that the relationship between East and West in contemporary jewelry became a real point of debate, and concepts like shared identities, distance, communication, and otherness were discussed.

But by trying to assess whether the seminar of the exhibition “did well,” this review might miss the bigger point made by our hosts. What should probably go on record here is a $100,000 indication that China wants to play in the contemporary jewelry big leagues. CAA isn’t the only one in China flexing its muscles: In late October of 2015, the Beijing International Contemporary Metal & Jewellery Art Exhibition (BIC.MAJA) opened at the China Millennium Monument Museum of Art, apparently displaying more than 300 works from artists of more than 20 countries. The pieces were selected via a juried submission process, and people like artist and gallerist Sofia Björkman (Sweden) and artists Lauren Kalman and Timothy Veske-McMahon (both United States) were flown out to attend the opening. The show lasted 16 days. Then, following in December, the similarly titled Beijing International Jewelry Art Exhibition was opened at the Innovation Park of Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology, as part of Beijing Design Week. In this case many renowned international schools with contemporary jewelry programs—like the Royal College of Art (United Kingdom), the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich (Germany), Alchimia Contemporary Jewelry School in Florence (Italy), and many more—were part of the organization committee. The selections were again made by submission, the show lasting 14 days (why all these spectacularly expensive shows only lasted a few weeks at the most is beyond me).

But Hangzhou’s insight to invite a sole European curator to organize their lineup signifies a greater respect for what’s happening elsewhere in the world, that they want to really connect to that. An easy assumption to make is that this gesture is also an accord. China wants to properly introduce “Western” contemporary jewelry to Chinese students and the Chinese public. And in return, it wants to be invited to play on Europe’s playground.

But what if it was in fact about bringing attention to its very own playground, asking international eyes to look at what’s been happening there all along? What if we were the ones who have the most to learn, and to gain? The relatively short history of China’s contemporary jewelry education programs makes it hard for some to accept that this is a history worth learning about. CAA, for example, only began to incorporate jewelry into its curriculum in 2004. Like in other schools, many of its current professors got their jewelry education in Europe or the US before returning to implement similarly structured programs into Chinese institutions. But a shorter history doesn’t necessarily make the work any less relevant. Maybe “we” just don’t yet know how to see it, and paying attention includes trying to empathize with cultures far away from what’s familiar or more accessible. We have to hold on to the fact that contemporary jewelry is academic, yes, but nothing without recognizing individual culture or identity.

Accordingly, the discovery of new work should also be in clear focus. And that’s what’s actually good about a big and seemingly boring survey; when paying attention there are many exciting things to be discovered.

A lot of the more intriguing pieces I discovered in the Body Alchemy exhibition did indeed come from Chinese artists. It seems right to conclude by briefly discussing some here—though most of the whys and hows of their origins remain a mystery to me. Chai Jichang’s enigmatic spikey, curly, black found-object brooches called The Series of Ruin—Heavy Metal (2013), seemed from another, darker universe. Ming Gu’s blobby neon, creature-like silicone objects (each called Miss.Guan (2013) and designated as rings yet strangely not identifiable as such) were freshly otherworldly and exciting. I just wished I could have picked them up! Xiao Liu’s Immortal Symbol Series (2012–2013) exerted a more subtle fascination; plastic shopping bags were completely transformed into 20 multicolored geometric forms. When the individual pendants are laid out symmetrically in the right way, the shapes—that I’m told are related to cut jade—create the figure of some kind of head totem …

By placing talented Chinese artists like these on the same list of big names from the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, the US, New Zealand, etc., the Chinese organizers of Body Alchemy are being smart. Their decision demonstrates that the sphere that’s been created around this field elsewhere in the world is appreciated. Europe should show mutual appreciation. That’s where the opportunity lies, I think, for galleries, museums, and collectors … It is beneficial for everyone to be more inclusive of Chinese and Asian jewelers and metalsmiths, to learn more about the contexts from where that work originates, and to take new initiative in seeking new work without having to be invited on a free ticket. Because much of what is being done over there is good and it doesn’t matter if there’s European influence or training in the mix or not, the work is still Chinese. Peters himself even said something of this nature to me, during an interview: “When a cat gives birth in an oven they will not be born small breads. They will still be cats.”[1]

[1] Ruudt Peters in conversation with author, June 2012.