Brooklyn Metal Works (BKMW), in New York, and WALKA Jewelry School, in Chile, are hubs of sorts, bringing jewelers together to learn new skills, show work, and support one another. As such, they’re important members of our jewelry community. In this interview, the founders of both businesses—who are all friends—talk about how they came into being, what they do, and how they do it, revealing similarities and differences in their teaching practices and how they run their respective organizations.

Both WALKA and BKMW comprise two key people as founders and collaborators. Tell us how working as a small team came about, and how and why it works for you.

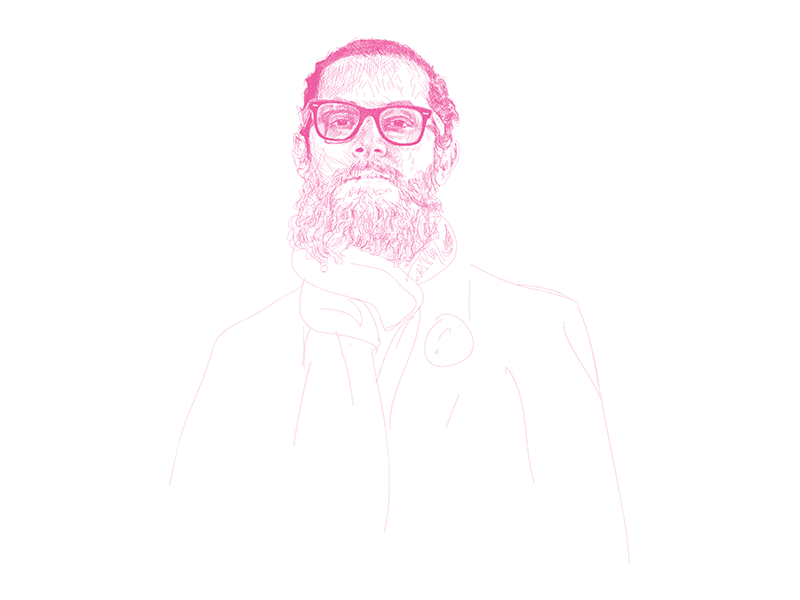

Brian Weissman: Erin and I met in grad school at SUNY New Paltz. Afterward, we moved to NYC where we worked, taught, and lived for about six years before Brooklyn Metal Works came into existence. During that entire time—grad school and living in NYC—we had been talking about what we could do to create community. After so many years of honing this idea, which became Brooklyn Metal Works, and discussing variations and moderations of this vision, we have an excellent understanding of what we want BKMW to be and what we hope it will evolve into.

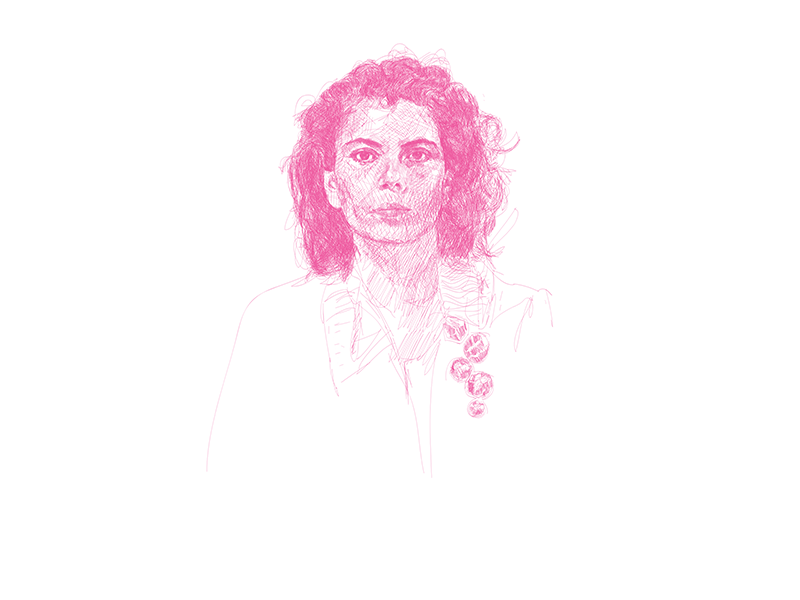

Erin S. Daily: Brian and I have lived and worked together in some capacity since grad school. We first taught together in the summer of 2003 at Snow Farm, in Massachusetts. These were formative years figuring out who we were as artists and what we wanted for our futures. This time laid the groundwork for understanding that we’re very different people in some ways, very similar in others, and complementary in our strengths and deficits. We’re able to continue working together on all fronts because this is how we’ve grown our relationship.

WALKA Jewelry School: We started as a very small studio in 2003. At the very beginning, Claudia was making jewelry using ox horn, leather, and small amounts of metal. She started teaching jewelry-making to Nano as a hobby. Because that was taking place at the beginning of our relationship, jewelry-making was the perfect “excuse” to spend more time together. We weren’t considering jewelry as a business project, so without a business plan we started working 12 hours per day, but we were happy, young, and in love with each other, and in love with jewelry as well.

Before jewelry-making, Claudia had trained in tourism business administration, so we applied our knowledge and backgrounds to our emerging small studio. After a few years, the studio got quite well known in Chile. Business-wise it was quite a successful venture, and we started making money. But we felt in our bellies—an intuition—that we were only producing jewelry like mad, and our souls and the creative depths of our work felt quite empty. We realized we want to do something more transcendental and profound, but weren’t sure what it was.

Then we found the book New Directions in Jewellery and realized a different kind of jewelry is possible! That year—2006—we meet Kevin Murray, Roseanne Bartley, and many artists from New Zealand and Australia who were in Santiago for The South Project Seminar. They presented Make the Common Precious. So again we thought, “that’s the thing we want to make.”

The following year we start planning an “iniciatical” trip to Melbourne. We closed our atelier to undertake a one-year self-funded and organized art residence in jewelry. We met amazing and generous colleagues and friends. We gave jewelry workshops for kids—our first teaching experience in jewelry. Claudia worked for Roseanne Bartley and Vicki Mason, learning tons from both of them (deep gratitude to both great makers!) and Nano did an art-cultural management internship at The South Project, then directed by Magdalena Moreno. We set up the exhibition Melbourne by WALKA at Craft Victoria Gallery and gave a handful of presentations and lectures about our work and experiences there.

When we returned to Santiago, we wanted to share this know-how and experience about contemporary jewelry. There was no such space in Santiago then, so we said, let’s make a space like that happen! We started to teach jewelry classes to very small groups of six students in 2008. After 10 years, WALKA Jewelry School has evolved a lot.

Did you model your businesses on other metal art studios or private schools you knew of? And how did you come to be running your schools and businesses?

Brian Weissman: Our biggest inspiration was UrbanGlass, in Brooklyn. We first came across this organization in graduate school. We both were really impressed with their gallery, studio spaces, their publication—Glass Quarterly—and the UrbanGlass mission. We kept wondering why something like this didn’t exist in the metals field. We were aware of several other spaces in the US for glass, metal, and ceramics, and the big craft schools, but none was exactly what we envisioned Brooklyn Metal Works would be.

During our first years in NYC, we realized many of our students would never mature into working artists because they couldn’t find a space to work independently. It’s hard to find an appropriate space to have a metals/jewelry studio in NYC. So most of our students became perpetual students—always taking classes just to have studio access. This meant they were working on class projects and not their own work.

Students would ask us what they could do to find studio space. There were no good answers. We didn’t want them working out of their apartments with compressed gasses or investing thousands of dollars in equipment they might only use four times a year.

We also felt Brooklyn needed a professional, safe, clean, and well-organized jewelry/metal studio . We had made a lot of connections throughout various facets of the jewelry, education, manufacturing, tools, and supply worlds, and wanted to help bring them all together and share this information, which historically is often hoarded or kept secret.

Erin S. Daily: We had always known we wanted to develop a studio/community in some capacity since grad school. It wasn’t until we moved to NYC that we understood it needed to be in Brooklyn, and why. One of our main goals was to raise the bar for health and safety standards. We kept seeing too many people working without much regard for, or understanding of, the environmental and physical impact. I like to think we’re moving the conversation in the right direction now and trying to model good working habits.

Another goal was to give jewelers a place to come together, share resources, and get acquainted. There wasn’t really such a location for people to find each other, and that seemed strange for NYC, a city with virtually everything. We looked for it, but couldn’t find it, so we tried to build it. Now BKMW is a hub of sorts.

WALKA Jewelry School: From the beginning we asked for help on this topic from Chilean government organizations, but we could only find a business model for creative business from David Parrish (UK). We felt we were doing well, but wanted some professional feedback. So we tried different possibilities. We worked with business students from the university in a collaborative project financed by a Chilean bank, we took marketing classes, and we joined a business incubator to develop our own business model in 2010. Since neither of us has any education in jewelry, craft, design, or art, we didn’t have any reference program to follow.

It was good to see our own business from a different perspective—from the outside—and we understand how the school and studio were working as a business. We confirmed that our way of learning and thinking works in a systemic way (we did things very intuitively at the beginning and still do now).

Both of your organizations offer teaching programs. What do you think makes you effective educators, and how do you measure this?

Brian Weissman: Because Erin and I have been living, working, teaching, and making work in NYC for so long and have worked in many different aspects of the metal and jewelry fields, we know where to send students and when. A lot of teachers in the city know just one aspect of the field, but Erin and I have diverse backgrounds and friends in all mediums. We also like introducing people and making connections. Our students and members are a great gauge of our effectiveness as teachers, but also of how great BKMW is for its members. So many members and students have launched and/or grown successful practices with us.

Erin S. Daily: I’ve been teaching art in some capacity since my early 20s. I was raised by teachers/professors who regularly discuss education in all aspects of life, and I was fortunate to have excellent role models. I’ve always been interested and engaged in the concepts and practices of teaching. It almost sounds cliche, but I did go to graduate school with the hopes of someday becoming a professor. The reality of finding a good teaching job in 2004 was laughably slim, and I eventually stopped applying. Besides, it wasn’t an option for one of us to take a job at a small school somewhere and hope the other person could find fulfilling work in our field. NYC afforded us the option to both have various jobs related to our profession.

After grad school I did teach for seven years at 92Y and for a year at University of the Arts. Currently, beyond all of the classes I teach at BKMW, I also teach Intro to Non-Ferrous Metals courses at Parsons The New School. I measure success as an effort to always do more, try something new, and base it on the outcome of past endeavors.

WALKA Jewelry School: Is there a way to measure how you teach jewelry making? If there is, it’s through the results of the alumni. Their projects and experience. Building the student’s self-confidence is important, but it’s a relationship that depends on the aims of each student. Every person is different and while at the beginning everyone learns the same basic metal techniques, what happens next? The teacher needs to find the strengths of each student; through this they can find their own voices. The teacher needs to be open and connected with the students, and by using psychological, creative, teaching, and couching methodologies, this is possible. Maybe it’s a bit early yet for us to measure. We need to keep working. Maybe in five years we’ll be ready to make that evaluation.

Do you have a teaching philosophy?

Brian Weissman: We embrace several teaching philosophies. First and foremost is that you should always be teaching the safest and most up-to-date practices available for the process or material you’re working with. Students are looking for different things, and it’s important to understand their needs both in and out of the studio. We get to know students and try not to force them through an educational meat grinder that might not actually prepare them for what they want—be it at the bench, in their art, or as a business.

Erin S. Daily: Brian and I are always in dialogue about how and why we teach, what we want our classes to cover, how we want BKMW to grow. In our advertising we say, “Our goal is to teach creative problem-solving through process and technique-based explorations, with projects designed to stimulate independent growth and learning. At BKMW students learn how to apply critical thinking and technical mastery to metalsmithing and jewelry making.” The takeaway: We want to teach not only how to do something, but also why. The why is important and often overlooked in many small jewelry/metals education settings, either due to lack of understanding by the instructor or lack of interest. To our way of thinking, the why is vital. If students can’t answer the why, they can’t reliably discern options or outcomes to help solve technical problems or cultivate dynamic designs.

WALKA Jewelry School: Every person learns in different ways. We develop a way of learning and seeing the world because of our family history, DNA, and traumas, for example. So you can use that information for creating something if you want it. We teach through our learning experience, so we don’t teach something that we haven’t experienced before. Our teaching philosophy? Embrace the moment.

The focus for your teaching programs seems slightly different. WALKA, you mention (on your website) non-traditional materials as being key to your offerings. BKMW, you talk about metal as being core to your suite of classes. How does this play out long-term in the type of jewelry produced by your students? For example, would you say your school produces a style of work or is known for particular materials and techniques?

Brian Weissman: While “metal” is definitely in our name, it’s by no means our only focus. One of my favorite thing to show guests when they visit is the diversity of types of jewelry made at BKMW and how no two artists’ work looks the same. With that said, however, we do an excellent job of facilitating classes in jewelry and metal. For students interested in more traditional and fine jewelry techniques, we’re able to prepare them to work well in that aspect of the jewelry world. Because of our friendships around NYC we can also help them explore and learn about almost any material they’re interested in.

Erin S. Daily: Metalsmithing is central to our studio/facility focus. It’s exactly our tools and equipment that are the foundation of our physical space. It’s the FDNY permits that we maintain, and the M-1 manufacturing zone that lets us keep compressed gases on site that is important to our artists and students. It’s our ventilation system, our chemical cabinets, our extensive array of stakes and hammer, our rolling mills and shears. This is what’s hard to come by in NYC and a very valuable service that we provide. So in this way, yes, metalsmithing is central. Because of this intense focus, many of our classes are geared toward metals, and we teach a wide variety of metalsmithing techniques and processes. It’s not our intention to teach an aesthetic style for students to adopt. Rather, we aim to give our students the necessary tools and critical thinking skills to develop their own creative approaches to jewelry.

Outside of the studio and conceptually, our relationship to materials is a different story. We’re all for people working across disciplines and creating art from a variety of materials. This is why we continue to develop relationships with other arts organizations and give students an opportunity to work outside metals. Our popular collaborations with UrbanGlass have been ongoing for years. This is one of the most exciting aspects of building BKMW—growing our community in diverse ways. We hope to soon incorporate clay and fiber collabs into our course offerings. Stay tuned!

WALKA Jewelry School: We’re known in Chile because our students can find their own voices. They apply all that they know to achieve a creative purpose. To have the opportunities to learn how you can melt different materials or disciplines is a privilege that our students have and, as teachers, we facilitate this process of self-knowledge. Hopefully our school doesn’t “produce” students with a style of work, or isn’t known for particular materials and techniques.

What would you like to do less of and more of where your schools are concerned?

Brian Weissman: Running a school and a business is a brutal process of learning everything the hard way. My biggest goal is to do less lease negotiating and one day own our own building.

Erin S. Daily: We recently hired MJ Tyson as our education coordinator. In that role, she has come in with great enthusiasm and energy and taken a lot of weight off of my shoulders.

Have your spaces, your curriculum offerings, and the focus for your businesses morphed and changed organically over time, or do you set in motion preplanned initiatives to move the schools and businesses in directed ways?

Brian Weissman: We’re always changing and evolving. I definitely have a vision for what I hope Brooklyn Metal Works will one day be, but every day you find out that you might not be able to take the direct path, you might need to go the long way.

Erin S. Daily: From the beginning we considered BKMW a grand experiment. We had no idea if it would work, or if what we thought it would be would in fact happen as imagined. So we always had a sense of flexibility and the possibility of change in mind. Too much rigidity could have killed the business and our spirits. Of course we have designs and try our best to steer the ship—it’s important to forge a path and stay strong in the process. We also want to stay in tune with potential alterations, to keep a read on what may need to change or grow.

We continue to reinvest in our tools and equipment, we continue our outreach to other institutions, we develop new curricula, we bring in new teachers, we host new events. Our physical space has evolved as well—we’ve taken new space in our building and created more studio space for artists. Also, importantly, we’ve hired several studio monitors who regularly make our lives more manageable.

WALKA Jewelry School: We believe in our intuition and we trust our way of doing projects. We think of the school as a community and as a “Make-Tank,” where we always discuss and take opinions from our students. For example if they want or need to learn a technique that isn’t in the program, we teach them anyway. And of course we as teachers learn a lot in this process. Maybe when we stop learning, that will be the time to close the school.

Your businesses differ in a variety of ways. Can you identify what your core business streams and areas are, and why you chose one type of thing over another? Do you think your location, your audience, or your own preferences or strengths and weaknesses, for example, have influenced these business choices?

Brian Weissman: Our two primary focuses right now are our members, to whom we rent dedicated space, and our students, who take classes and workshops with us. NYC has definitely inspired the studio aspect of BKMW because studio space is important in a city where space is limited. NYC also tends to have students who are more interested in fine, fashion, and limited-production jewelry, so some of our classes focus on the skills needed to make that type of work.

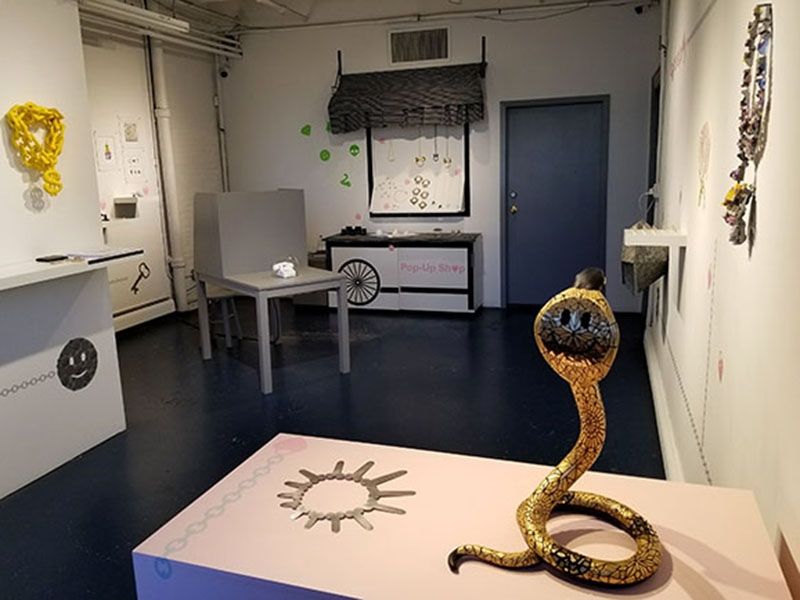

Our exhibition space is our mouthpiece. We use it to promote what we consider interesting and important. I would say that location has little influence on the exhibition space because it deals with our interest in contemporary jewelry and art, which goes far beyond NYC. Side note: Because we often have students who are interested in more traditional jewelry, we see the gallery as an opportunity to expose them—via the exhibition space, instructors, or sample projects—to more diverse work.

Erin S. Daily: One main feature of our business is our Artist Lecture Series, and it certainly relies on our location. We have relationships with contemporary art jewelry galleries in the Northeast, and since NYC is a travel hub/destination with artists often traveling through or to NYC, we take advantage of this proximity to invite artists to give a lecture or workshop. We’ve been so fortunate to have support from the galleries as well as artists to develop this lecture series. Over the past seven years we’ve had over 70 artists speak here.

WALKA, can you tell us how you exhibit your own and students’ and others’ work?

WALKA Jewelry School: We offer the space to visiting teachers and colleagues (especially for the WE WALKA International Workshop Educational Program). We’ve had exhibitions by Iris Eichenberg, Caroline Broadhead, Jorge Manilla, Mia Maljojoki, Mari Ishikawa, Anastasia Young, Sayumi Yokouchi, Marta Mattson, Klara Brynge, Jiro Kamata, and Tanel Veenre, among others. We periodically exhibit our students’ work. We don’t show too much our own work in this space.

BKMW alluded to New York having a strong metalsmithing history and community. It’s exciting having New York Jewelry Week added to the mix. WALKA, can you give us some background on metalworking in your city?

WALKA Jewelry School: Our strongest metalsmithing history is based in Mapuche jewelry, aboriginal pre-Columbian body adornment. Before the dictatorship, Arts and Crafts had a very strong scene here (in the 60s and 70s), then after 40 years of cultural blackout we slowly started recovering old crafts techniques, materials, and arts-related disciplines. During the 90s, Victor Muñoz, a Chilean jewelry teacher who studied in Denmark, arrived in Santiago and started a private jewelry school. Now some of their students make and teach. He was Claudia’s teacher.

But the event that creates a “before and after” in the Chilean scene was The Grey Area Symposium, in Mexico in 2010, organized by curator Valeria Vallarta. It was the first time that jewelers from all of Latin America came together in the same place. We start creating jewelers’ associations and exhibitions. The most important thing was discussing and learning what contemporary jewelry means. Our scene is therefore still young and evolving.

BKMW, in your interview with AJF back in 2016 you spoke about not having much time for your own work because the school, your many projects, and business is all-consuming. Has this changed?

Brian Weissman: We have even less time as we continue to push forward in every direction. I’m personally at a point where I’d really like more time to develop my “macaroni art.” I have several pieces I’ve started but only a few failed samples to show for my last year of working at the bench.

Erin S. Daily: In the past two years Brian and I have had the good fortune to be included in several museum shows. Considering that both of us create objects more than jewelry, this is an accomplishment. I do make jewelry, of course, but it isn’t always my main consideration for art explorations, and it’s harder to show objects than jewelry. We’re working on changing this lack of representation in the field. It’s difficult to keep up an art practice no matter the circumstances. It really is a matter of priority, and the tide is shifting back toward us having more dedicated time to make art. We recently moved our private studio off of the main floor of BKMW. I’m also looking forward to a residency this January in which I hope to kick-start a new creative project.

What plans do you all have for your respective schools and businesses heading into the future, and how do you negotiate what to pursue if you have divergent views?

Brian Weissman: We’re scheduled to take more space in the building. We hope to offer more classes and more studio space. We’re also launching our Specific Gravity online store to promote the artists who work out of Brooklyn Metal Works. My hope is that one day it will become a brick and mortar location. We also have a bunch of other projects that it’s still too early to speak about.

WALKA Jewelry School: Our strategy: Keep working for years. Our solution to divergent views: discussion, love, and patience.

What do you most love about your businesses and teaching practices?

Brian Weissman: The community we’ve built is wonderful. People share with each other, help each other out, and become great friends and collaborators. It’s a really beautiful thing to be a part of.

WALKA Jewelry School: This is a constant learning process for us. We can just be deeply grateful to craft/art/design. They give us freedom and purpose.