New York-based jewelry artist Annie Fensterstock is known for her intricate, richly adorned designs which utilize ancient goldsmithing techniques and traditional materials such as gold, silver, and precious stones. Her work, while undeniably fresh in its approach, also frequently references popular Renaissance, Baroque, or Art Nouveau styles. This was evident in the jewelry on view in her one-woman show at de novo. In this conversation, we not only discuss Fensterstock’s background, influences, and inspiration, but the work in this exhibition.

Allie Farlowe: Annie, did you know at a young age that you would pursue a creative career? What kindled your initial desire to make jewelry?

Annie Fensterstock: I grew up in a family of artists. My grandmother was a painter and my mother was an art teacher. My grandmother taught me how to draw at an early age and my mother kept our house stocked with art supplies. I learned early on that I felt most comfortable and empowered with pens and paper. I went to art school thinking I would go into illustration. I stumbled upon jewelry in an attempt to learn how to make a proper clasp for the beaded necklaces I was making for friends and family, and for my brothers to sell at Grateful Dead shows. I never turned back.

In 1993 you received a BFA from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. You studied there under Eugene Pijanowski and Hiroko Sato Pijanowski. The Pijanowskis are known for their explorations of Japanese metalsmithing techniques, and they are credited for introducing these approaches to American artists. Please tell us how you feel the Pijanowskis have influenced your work. Also, was there one important lesson that you learned during those years as a student?

Annie Fensterstock: The Pijanowskis’ influence is probably less obvious in my actual work than in how I approach the creative process. Hiroko Sato Pijanowski, in particular, challenged me on every level—from research to design to execution. She forced me to question my motives, my approach, and how I see things—externally and internally. She encouraged me to explore further, search harder, and question the idea of what is precious. The most important lesson? Embrace failure.

Your work reflects a love of ancient styles and techniques. The bracelets, earrings, rings, and necklaces in the de novo exhibition reveal connections to Renaissance, Baroque, and Art Nouveau jewelry. This historical style-hopping is quite unique in the studio jewelry field, and brings to mind the versatility of restorers. How would you describe the relationship that you have to jewelry history?

Annie Fensterstock: I’ve always loved studying art history and learning how technological advances have shaped design throughout the years. My profound connection to art history and jewelry history has always permeated my own explorations of adornment and ornamentation. Written and visual history informs our ideas, values, and beliefs. By using ancient goldsmithing techniques in a distinctly modern fashion, I am able to expand upon these existing ideas, push our cultural limitations, and discover a new vantage point.

The work at de novo dates from 2013–2016. Does this body of work represent any new directions or developments in your jewelry?

Annie Fensterstock: Through my work, I am continuously investigating the relationship between adornment and beauty, fashion and history, tradition and trend. Each body of work is an extension of its predecessor, with a distinct evolution and a fresh vocabulary of expression. This current body of work plays with the juxtaposition of contrasting lines—sharp, jagged edges against soft yet dramatic feminine curves. There’s a particular focus on lockets—modern heirlooms. I’ve always been intrigued by the historical significance of lockets—keepers of photographs, memories, hair, ashes, or even poison. Through my lockets, I seek to create intricate vessels for keeping secrets—sentimental mementoes that protect and transport stories through generations.

The piece Aria Cuff stood out among those included in the exhibition. This cuff is a richly adorned, intricate work. Like many examples of your jewelry, it combines multiple metals, precious stones, and a dramatic playfulness of light and dark. Is creating this sense of drama important to you? Also, can you talk a little about Aria Cuff’s inspiration, the design process, and the significance of the title?

Annie Fensterstock: With the Aria Cuff, I attempted to create a piece that strongly embodies glittering, dynamic beauty along with its darker, mysterious underlinings. There are subtleties of these components throughout most of my work, but the Aria Cuff is quite fierce in its expression. An aria is an accompanied elaborate melody sung (as in an opera) by a single voice. Creating a sense of drama in this melody is not so important to me; rather I hope it evokes emotion in some way. The rhythm and movement of the Aria Cuff truly comes to life when the piece is put on. The interaction with the human body when it’s worn is meant to create an experience much like a song that resonates.

You often utilize asymmetry in your work, as seen in Mismatch Earrings. Could you explain why incorporating asymmetry is appealing to you?

Annie Fensterstock: I’ve always been drawn to the idea of balance through asymmetry. Asymmetrical balance challenges both the artist and the viewer to explore negative space, darkness/light, and spatial relations. Deliberately disturbing balance altogether further engages the viewer (or wearer) to step outside of their natural comfort zone and either question or embrace the disorder.

In your artist statement, you state that you alloy your own gold to create custom colors for specific works. When and why did you begin doing this? Is there a particular alloy that you’re drawn to, and why?

Annie Fensterstock: I learned about alloying gold while studying at the Jewelry Arts Institute in New York during my college summers. We alloyed our metal to create the ideal 22-karat gold for granulation. Alloying my own gold now allows me to control the color of the metal. I often employ several colors of gold in one piece—shades of yellow, pink, and white. Balancing colors, along with texture, pattern, and weight, creates dimension and energy that permeates the work.

Your work can be found in many galleries and boutiques. Online searches of your jewelry produced abundant results. Could you share with us how you balance time for creativity with the production side of your business?

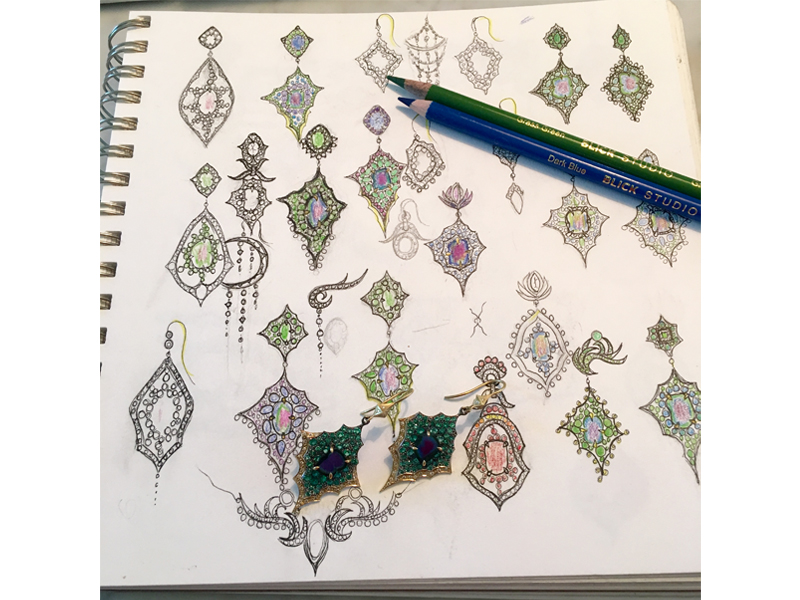

Annie Fensterstock: I am lucky to have a fantastic team of goldsmiths working with me. Most of my time now is spent focusing on design, choosing stones, and managing the production team. My hands are still on every piece that comes out of the studio—I do all of the finishing myself. My husband manages the business, so we get to spend our days together. He plays a big part in helping to choose which pieces from my sketch book get executed, and then prices them out to make sure they make sense!

What’s next for you? Any new explorations, projects, or directions?

Annie Fensterstock: My exploration is continuous. One project directs to the next—it’s not predetermined. I sketch and sketch and sketch and then create. I’m constantly growing as an artist and as a designer, and I hope to continue creating jewelry that empowers and celebrates the wearer.

You’ve said that music is among the things that provide “continuous inspiration.” What music are you listening to now? Do you listen to music while you work? Is David Bowie still an inspirational figure?

Annie Fensterstock: I’ve always listened to music while I work, and it always varies. I’ll roam from Yo La Tengo to The Velvet Underground to Billie Holiday to The National to my kids’ current obsession (the Hamilton soundtrack). David Bowie remains a constant. Music has always played a tremendous part in my creative process. It taps into the imagination and rustles memories. It stimulates emotion and inspires clarity. It’s intricately woven through each piece I create. As stated perfectly by Beethoven, “Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy. Music is the electrical soil in which the spirit lives, thinks and invents.”

Thank you.

The pieces in this exhibition range in price from about $300 to $50,000.

INDEX IMAGE: Annie Fensterstock, Nouveau & Emerald Fan Cuffs, 2016, 22-karat yellow gold, sterling silver, diamonds, opal, emerald, 57 x 54 x 25.5 mm, photo: Christine Blackburne