Susan Cummins: You are now 90-years-old, and you have accomplished many things in your lifetime. What are you most proud of?

Bruno Martinazzi: To get my ideas across, I cite Gianbattista Vico, an Italian philosopher and author of the volume Principi di Scienza Nuova, written between 1725 and 1744. In Volume 1, Part II, line 3, he writes, “First human beings hear without attention, then they keep attention with confused and touched souls, and finally, they reflect with pure minds.” From that principle, art and poems take form.

Susan Cummins: You are now 90-years-old, and you have accomplished many things in your lifetime. What are you most proud of?

Bruno Martinazzi: To get my ideas across, I cite Gianbattista Vico, an Italian philosopher and author of the volume Principi di Scienza Nuova, written between 1725 and 1744. In Volume 1, Part II, line 3, he writes, “First human beings hear without attention, then they keep attention with confused and touched souls, and finally, they reflect with pure minds.” From that principle, art and poems take form.

“Being” is the transformation from being passive to being active, doing what you are able to do well, being honest with yourself and with others, and changing from the silence of the spectator to the tension of a creative being and the author of your own story. “Loving” signifies a way to understand that what you are doing is done with joy, not only for yourself, but also toward others, toward nature, toward the world, and it is energetic.

Can you tell us the story of when you knew you wanted to be a jeweler or a sculptor? Which came first?

Bruno Martinazzi: Many things have brought me to work in gold and in stone. The experience of the war and the struggle within the partisan movement—I participated for 20 years—created a strong desire to feel free, and that is the emotion that I feel when I realize a sculpture or a piece of jewelry. Gold and stone resist time, and the idea of freedom remains in the heart of the human being. When I was young, other forms of art attracted me, first music and painting then goldsmithing and sculpture. I started to become a goldsmith thinking that it would keep me free in this way, and then I started to love it, and so I left painting, and without even noticing, I passed to sculpture.

Bruno Martinazzi: Alpinism, the mountain, the rocks, and the horizons—these are the things that made me feel free, and I loved this feeling. Sculpting stones that have existed for hundreds of millions of years and touching this form of time fascinated me.

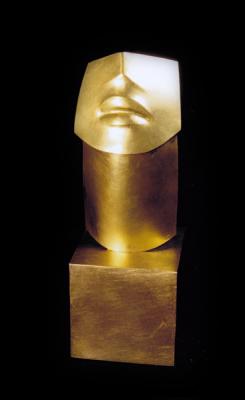

You are famous for jewelry depicting lips, eyes, and fingers in particular. Why these images?

Bruno Martinazzi: Lips, eyes, and fingers are the details of a universal image, of an entire figure that is longing for form. I started with them in 1968, and at that time, they were like parts of a world that breaks up in crisis. After that, they became symbols and principles that represented the whole. They are born as the act of breaking up, but in 1967–68, along with the peace movement in Europe, I hoped for a better world.

Bruno Martinazzi: Everything is one and one is everything. I think I am near to a certain type of pantheism. The wind, the earth, the sea, the human being, the nature, the beasts, everything takes part in one unique and eternal story. I try to understand that story and to tell it with my language, which gives form to what I inherited from the past, but I feel it with the soul of today. It is difficult to describe a reality, which we can hardly imagine or understand. In my opinion, only a change of language is not enough.

Do you work with stoneworkers or other craftspeople, or do you do all your stone carving and gold work yourself? How does your studio run?

Bruno Martinazzi: I have always worked on my own, and each time, it is as if I fall in love again—the joy of seeing them grow, touching them, picking them up, and giving them life. Only in the case of very big sculptures do I need help from assistants. Then I go to Pietrasanta, in Versilia, where I find excellent workers. Artists from all over the world go there.

What do you want to spend your time doing now?

Bruno Martinazzi: For me, to create a small object or bas-relief is an activity for my body and mind that I cannot resist. It is like breathing. I need it. Metalwork does not need muscles. And I discovered that I like writing.

What are you reading, seeing, or hearing recently that you have loved?

Bruno Martinazzi: I am very slow at reading, and now it is more difficult to concentrate. As a young man, I read more, and I read everything from the Bible to fantasy. Now I am more selective, and as I said already, I feel near to Pantheism, so I prefer authors like Parmenide, Giordano Bruno, and Schelling. Recently, I read about women participating in the partisan movement. It was pages like diaries. I was very touched. I felt the reality of that period and was so moved that I had to stop. In the center of my artistic research, there is always the human being—his suffering, his joy, his ignorance, and his hope.