In the mid-90s, to use the word “curating” in the field of contemporary jewelry must have sounded exaggerated or simply incomprehensible. To think with and through the format of an exhibition in order to transform it into a discursive medium was quite unusual, especially if the statement was coming from an independent curator, who was not a maker herself, and not affiliated with an institution, as was my case. For some years, the “Off-Schmuck” circuit in Munich has given a new visibility to the activity of curating, even if it is mostly reduced to issues of arrangement and display. In a wider context, a debate is taking place—for example the international seminar Curating Craft, initiated by Jorunn Veiteberg and myself in 2012; the book edited by André Gali, Crafting Exhibitions (Norwegian Crafts, 2015); or the recent AJF publication, Shows and Tales, a valuable contribution to the history and critique of jewelry exhibitions.

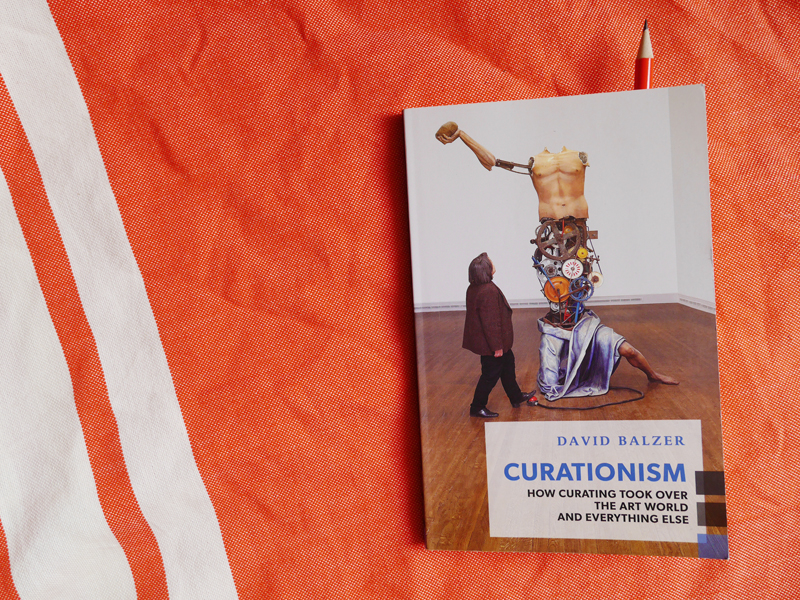

At the same time, one finds the term “curated by” in increasingly unexpected contexts: the shop window of a fashion store in Bangkok was curated by jewelry designer Ek Thongprasert, and a billboard in a tram stop in Zurich advertised a G-Star Denim collection curated by musician Pharrell Williams, just to mention two recent examples. The inflationary use of the word “curating” is encouraging people to define its changing meaning lest (or as?) it becomes devalued (a similar over-use of the word “craft” is discussed in an article by Gareth Neal.) When I saw David Balzer’s book at the Palais de Tokyo’s bookshop in Paris, I thought it was time to know more about this phenomenon.

There is indeed an irony in finding this book in the institution that promoted relational aesthetics, a genre also known as “curator’s art” with skeptical connotations. Indeed, the book fulfills in an entertaining way its quest to investigate the “curationist era,” an expression coined by the author. Balzer, an art critic based in Toronto, surveys the origins and history of the curator’s figure, tracing back to the Roman empire, where the “curatores” were bureaucrats, administrating departments of public work. He walks us through centuries of curatorial practices, based on caring (from the curator as a healer and priest in the Middle Ages to the curator as alchemist for social change in the contemporary biennials); on the celebration of curiosity (from the Louvre’s loot-keepers to the first director of MoMA); and more recently, on the authorial dimension of curating through grouping and selecting (from Szeemann as father of all professional curators to celebrity curators, coming from the entertainment industry, who infiltrate the profession in an amateurish way). Dissecting the multilayered roles that a curator can assume as a connoisseur, dealer, critic, institutional agent, or even artist, the author places the activity of curating in a cultural arena that reaches far beyond the art world, and includes music festivals, gastronomy, and fashion. Sentences like “Sometimes you have to climb a mountain to properly curate a sock” testify to the irony that the author employs to approach the topic.

I enjoy that the author is extremely informed but not super-rigorous; he is proud to state that the book hardly contains references and has no footnotes. This slight understatement makes the book unleash what Deleuze and Guattari would call a “rhizomatic potential,” in a generous way. The book is thus particularly inspiring for me because it reconnects me with other texts I have read in the past and urges me to revisit what I thought when I read them. Its timely engagement with the topic of curating will challenge everybody occupied in communicating their own work and the work of others.

Sometimes, it is great to acknowledge what a book does to you instead of what it is strictly about—especially in summer.