When you hear someone referred to as a “collector,” what comes to mind?

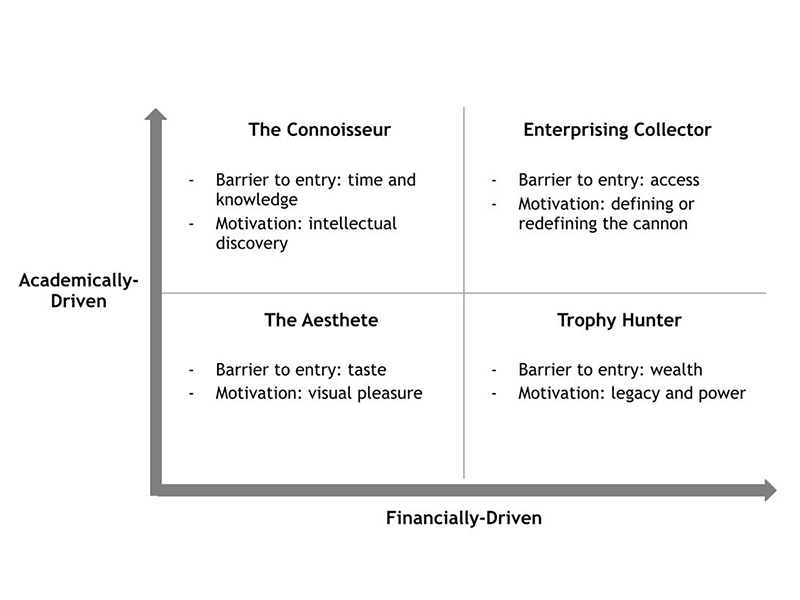

So often, collectors are understood exclusively through their effect on the art market and the potential of their eventual legacy giving. Those museum wings aren’t going to name themselves, after all. Artists dream of the collector who sees their creative genius and changes the course of their careers. In a 2018 Artsy article, Evan Beard helpfully defined the four personas of a collector as The Connoisseur, The Aesthete, The Trophy Hunter, and The Enterprising Collector, then rated each one’s motivation from academically to financially driven. Do you see yourself in this graph?

Art Jewelry Forum has a robust archive of interviews[1] with established art jewelry collectors who could locate themselves on this graph. These collectors, among many others, include Helen Drutt, who donated her collection to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Lois Boardman, who donated her collection to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Within art jewelry, these collectors are the type Evan Beard describes, the ones who are aware of the effect of their actions on the art jewelry world and who embrace the title of collector.

While it’s true that collectors can be the makers of artists’ careers, the drivers of the marketplace, and the major givers to museums, they have to start somewhere. Before they become capital “C” collectors, they are simply interested people who surround themselves with objects they enjoy.

Art jewelry is especially approachable to someone newly discovering an interest in objects because of the added level of engagement one experiences by wearing and interacting with the work. The accessible price point of many of these fantastic objects, with prices well below that of a painting, makes art jewelry an exciting locus for discovering how a collector is eventually made.

Collectors don’t fall from the sky fully formed and cognizant of their influence on the marketplace. They grow and are nurtured by relationships with artists, gallerists, their peers, and their own curiosity.

So let’s start there, with curiosity. Curious people derive joy from looking deeply at objects, and when a piece ignites a person’s curiosity, there’s an impulse to know more. Whether through its unorthodox material use, the challenge to and even subversion of a recognizable form of jewelry, or via an engaging conversation with the artist, art jewelry often sparks curiosity. Because art jewelry deviates from the norm, it’s a field ripe for someone with an inquisitive bent.

Once people’s curiosity is piqued and they’ve had conversations with an artist (or two), and purchased a piece (or 20), they start developing personal preferences. Every person’s choices are influenced by their unique background and experience, whether it’s a piece of jewelry or a painting. A preference could be toward a color, a shape, a material, or a style. Combined, these preferences guide a person to acquire art jewelry that is representative of their tastes. For example, one person may prefer figurative beadwork necklaces while another might go for geometric enamel brooches. A person’s preference will evolve with exposure to a variety of options, but some preferences are strongly ingrained. If a person hates a certain color, it will take a powerful piece of art to overcome that distaste. Personal preferences cover a broad range, including subject, material, forms, style, weight, color, and object type—the particulars are as unique as each person.

There are also situational preferences. For example, concerns about storage might affect a person’s ability to amass a large jewelry collection—though it didn’t stop Lois Boardman from growing her collection, often storing them under her bed in discarded shoeboxes. Even so, deciding on a purchase involves a lot of considerations, including budget limitations, the ability to store a piece, whether it’s wearable, and how much room is left, say, in your luggage, if you’re buying while on a trip. So many thoughts are running through a person’s mind as they consider a purchase, and only some of them are about the piece itself. With art jewelry, a person’s clothing style might even influence choices.

The photo above shows part of a former corporate executive’s collection, illustrating her initial preference for long, narrow brooches, which were chosen to complement the lapel of her suit jackets. Over time she became bolder with her jewelry as corporate dress norms eased, and her choices became less vertical because they were no longer confined to the lapel. Examples of those appear immediately below.

As curiosity expands and preferences develop, a person will most likely build relationships with someone in the field. This second person—an artist, a gallerist, a curator, or a colleague similarly intrigued by art jewelry—spurs their interest by introducing new artists, events, and concepts. Sharing an interest with someone like-minded is an important part of the evolution of a person’s ideas, allowing for conversation to develop more awareness of themselves and their newfound interest. These relationships can be all business or develop into deep friendships that last a lifetime. In whatever way they show up, these relationships help broaden horizons through exposure to new ideas.

An additional part of exposure to new ideas comes from accessing resources such as online platforms like Artsy, Art Jewelry Forum, The Jewelry Library, and Klimt02.[2] These, along with in-person events like the American Craft Council’s[3] craft fairs, jewelry-focused gallery[4] openings, and design fairs like Design Miami/,[5] provide education that fuels a person’s interests. These key resources expose people to the rich complexity of art jewelry and continue the cycle of engaging curiosity, developing preferences, and building relationships.

At this point, the person may not consider themselves a collector quite yet. Chances are, though, that they’re very excited about their most recent purchase—wouldn’t you be?! Art jewelry provides a unique sharing opportunity through the act of wearing. It isn’t possible to wear a piece of art jewelry in public without getting a few odd looks. The wearer may even have the opportunity to share their newfound knowledge about the artist, the material, the process, and the field with those who are curious enough to ask. They become joyful promoters of art jewelry, taking pleasure in the attention the visibility brings, not to themselves, but to the talented artists who have made the beautiful objects they’re wearing.

The act of wearing for some leads them to become active promoters of the field; they have gone beyond providing support by only purchasing pieces of art jewelry. Suzanne Walsh comes to mind as a person who joyfully wears her pieces and features them on Instagram.[6] Her zeal is contagious as she shares the jewelry she loves, and her playful selections underline her personality, even in business casual. Another active promoter is Jessica Todd, a young curator and writer who features her latest acquisitions on social media using the hashtags #WearArtEveryDay and #YoungCollectors.[7]

At this point, the person has gone through stages of curiosity, preference development, self-education, and the engaging feedback of wearing art jewelry. They might even be actively promoting their recently acquired pieces online or in-person as they wear the work in the world. They’ve become someone who actively acquires pieces, amassing an impressive array of work. This person might be your neighbor, your colleague, or your friend. It could even be the very artist you’re interested in, as many artists are also collectors, trading work with other artists and amassing an impressive collection through their networks. Even so, they may not consider themselves a collector in a formal sense. There is a psychological shift in identity that happens between accumulation and appreciation, where collecting becomes a practice, even a lifestyle. For some, the collector identity is a way to make a mark on the world.

Whoever this person is, they may never frame their curiosity as “intellectual discovery driven by academic interest,” as in one of the collector personas defined by Evan Beard. But, what’s more important than the label is that they’ve come to understand how art jewelry gives them personal joy, an appreciation that fuels the excitement of discovery.

So, pehaps after reading this, you’ll consider your relationship to the pieces you acquire. You just might decide you’re on the path to being a collector, or perhaps that you’re already a full-fledged, capital “C” collector, defined on your own unique terms.

References

Evan Beard, The Four Tribes of Art Collectors, Artsy, Jan. 22, 2018.

Karen Chernick, Mera Rubell Shares 5 Tips for New Collectors, Artsy, Dec. 4, 2019.

Sophie Haigney, Accumulation and Appreciation, Affidavit, Dec. 15, 2020.

Debra Hand, “Crucial Tip for Artists and Collectors: Why Some Art Sells for $1,000,000 versus $1,000,” Black Art in America. Sept. 8, 2019.

Claire Voon, How Collectors Can Establish Meaningful Connections with Artists, Artsy, Nov. 4, 2020.

[4] See AJF’s gallery pages.

[6] https://www.instagram.com/sewalshesq/.

[7] https://www.instagram.com/jesstoddstudio/