There’s a new genre of contemporary jewelry emerging in Melbourne. On the surface it appears connected through a shared aesthetic temperament. However, what more concretely defines this movement is a collective concern with new forms of social and cultural mediation and a sense of irreverence. The artists at the forefront of this development in practice engage in varying degrees of resolution, finish, and technical expertise in their projects and artworks. They also routinely confront notions of preciousness, and use value, body politics, and the political agency of the thing through the processes of making, adornment, and display. Undeniably influenced by the unmonumental in contemporary sculpture,[1] these often diminutive and accumulative practices nonetheless have a strength and presence. There’s also an emphasis on infiltration and parasitism as working methodologies through which to approach the contexts of contemporary jewelry and visual art: experimentation with the limits of these contexts, and how they can be blended and blurred, by creating artworks that move fluidly from surface to surface, from body to street to gallery wall.

It might seem that the work of artists Clementine Edwards, Debris Facility Pty Ltd., and Rebecca Thomas relates to an international wave of sloppy craft (and how this idea might intersect with the DIY movement) or the notion of a “calculated sloppiness” reported by Glenn Adamson in When Craft Gets Sloppy.[2] However, I prefer to describe these artworks as following a tradition of “inspired amateurism”[3] relating to the positive and generative forces of punk. The irreverence of punk, often articulated through its formal and stylistic tropes, was a hook, one that quite literally pierced through the skin in an attempt to reject or provide alternatives to the political and cultural status quo of the UK and the US in the 1970s.

The mediation performed by these artists to manipulate the conventions of fine art by adapting or evading its frameworks and contexts reflects this punk approach. It’s not only evident in the physical attributes of their artworks but in an adaptability and flexibility toward subject, site, and process that is enabled by the philosophical dimensions of punk and inspired amateurism. Equally, these artworks are a response to the culture and political dimensions of our time.

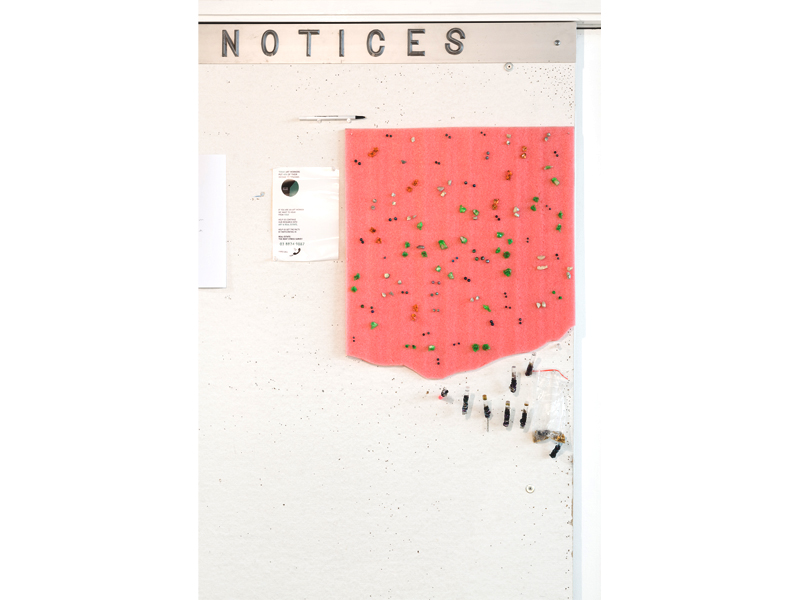

Take for instance a recent project by Edwards: the Frankenstein Backpack Show (2016–ongoing, coordinated with Ruby Fitzgerald and Brighid Fitzgerald) that featured Edwards and six other artists.[4] Each one contributed small attachable works, ranging from the meticulously handmade to the found object, to a backpack that itself appeared to be hand stitched from pieces of black leather. The backpack had an informal launch in a café in Brunswick East before it continued to be shown around Melbourne as it was worn for days or even months by one of the participants before being passed on to another. Not only a functional and useful object, the backpack operated on both micro and macro levels: Artworks were literally attached to the backpack’s surface like parasites, but it also simultaneously functioned as a parasitic act by informally infiltrating other spaces and contexts while being worn.

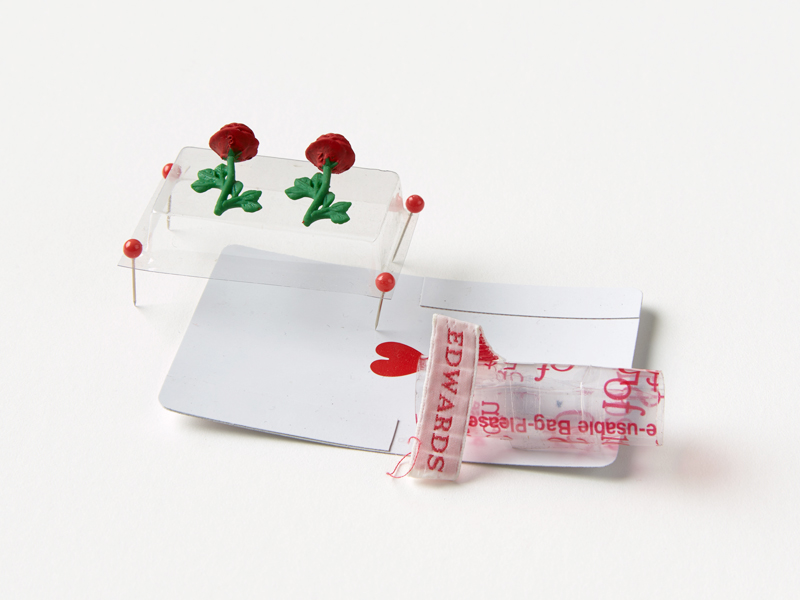

Edwards’s artworks range in scale and function from individual wearable jewelry pieces and minutiae to small-scale sculptures across spatial installations and performative wearable projects. At times her work is intricately crafted using plastic and metal casting techniques or, like Yellow Pendant (2014), formally composed into asymmetrical compositions using found materials in brooch and pendant settings. These works are as likely to be shown worn on the body or in the contemporary visual art space imbedded in the wall. More broadly, Edwards is interested in the interpersonal interaction with artworks. She is attracted to the physical and theoretical frameworks created by contemporary jewelry: the ability of jewelry to provide social mediation through its inherent mobility, and through the possibilities or qualities of casual conversationality, portability, and humor.

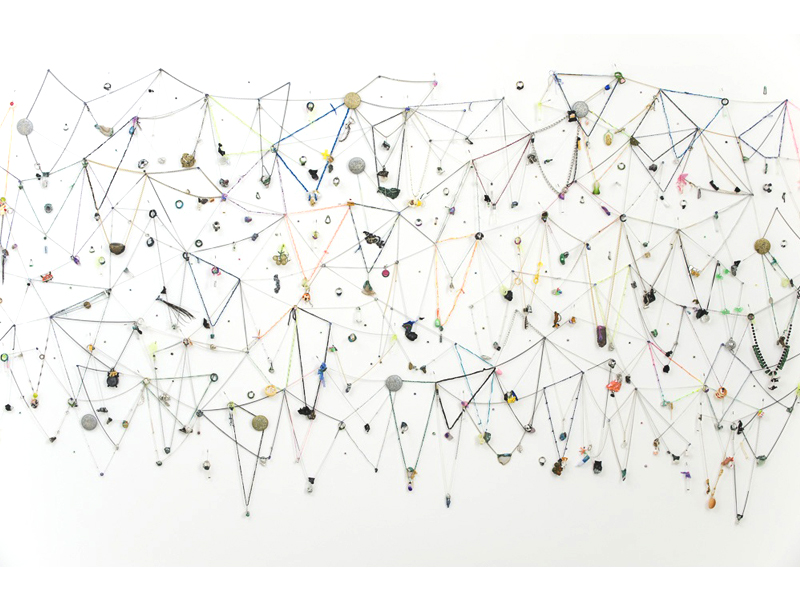

Debris Facility’s jewelry works have been presented cobwebbed across gallery walls, to be worn and purchased as individual pieces or experienced as complete installations such as Angora Aurora: 365 Split Crumbs (2010), presented in the group exhibition Territorial Pissings at Utopian Slumps gallery in Melbourne. Chain, nylon cord, and rubber variously suspend miniature trinkets in the shape of food, melted plastic forms, tiny sealed vials of glitter, miniature tea strainers in the form of teapots, costume jewelry, jump rings, and spray-painted biscuits. The performative aspects and wearability of jewelry have cohered with Debris Personality’s sculptural practice for close to 10 years now. The Facility’s artworks and practice can be seen as the progenitor of ideas of infiltration and parasitism.

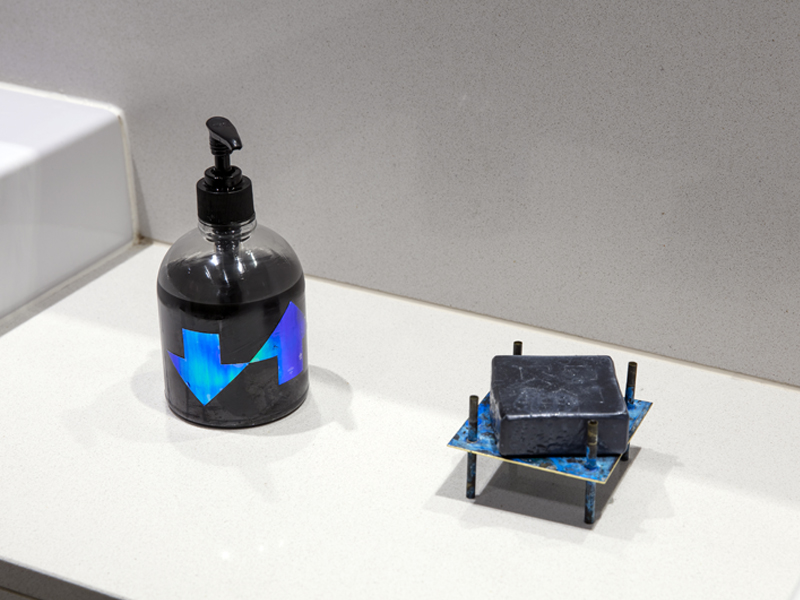

Infiltration and parasitism are particularly evident in the Facility’s approach to subject, site, and function. In work for the exhibition The Trouble with Remuneration (2016), at West Space in Melbourne, the Facility undertook a variety of activities, including a performative lecture that included the outcomes stated in the title of the artwork Final Quarterly Report, Showcase, Staff Update, and Key Performance Indicator Evaluations. Gallery staff were invited to wear the jewelry on display in the exhibition and in doing so in effect became employees of the Facility, literally adorned with the parasitic elements of the practice. Recently, for the TarraWarra Biennial: Endless Circulation, at the TarraWarra Museum of Art in Victoria, the artist produced (in collaboration with Rebecca Thomas) holders and dispensers for bar and liquid soap for Excipient (2016–2222). The dispensers were not displayed within the white cube but rather were intended to infiltrate the museum bathrooms, offering activated charcoal soap for visitor use. How stand-alone Daily Disposable collections of jewelry by the artist might infiltrate larger installations and projects and further commercialize or fund the Facility’s artistic practice is an ongoing concern.

Rebecca Thomas’s interest in jewelry stems from a fascination with specific historical forms. This interest spans from Etruscan and ecclesiastical jewelry to Victorian mourning jewelry and Berlin Iron. The influence of these sources manifests in her work through experimentation with religious symbols and the frequent use of saw-piercing techniques to produce decorative forms and detailing. It is also this quality that links her work to the provocation and irreverence inherent in punk sensibilities and politics.

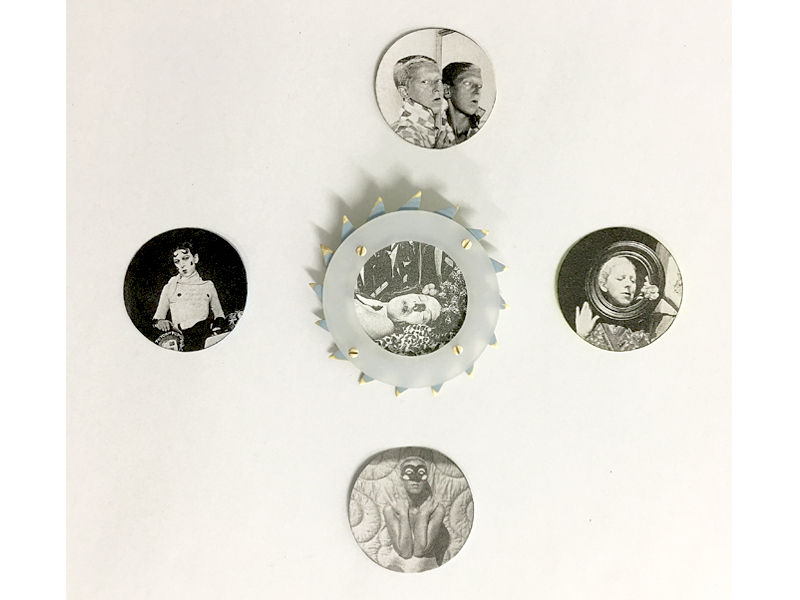

Despite the rarefied or even religious significance of many of the primary artistic sources in Thomas’s artworks, these forms are given a contemporary political inflection. Crosses are segmented, bisected, or so significantly abstracted as to appear as pure geometric forms in a shift that is reminiscent of Kazimir Malevich’s transformative and political response to Russian religious iconography through the production and proliferation of the black square. Metal is saw pierced in curvaceous and undulating lines that evoke decorative ironwork, only to be coated in copper oxides that blacken and punctuate the surface with bright color. In Florid Oxides Earrings (2016), the surface of the earrings is dark black and brown between intense sections of bright cobalt blue. These encrusted and florid works sit parallel to the ear, hanging below the lobe and alongside the neck. While the patinated works are seductive in appearance, the oxide could possibly irritate the skin and eyes if it came into direct contact with the body. In the case of Brooch for Claude (2016), Thomas has created a fitting with five interchangeable photographic portraits of French avant-garde feminist artist Claude Cahun. The images are derived from Cahun’s self-portraits and, encircled in this way, they perform an act of idolatry. Secured onto the fitting via a flat Perspex ring framing, the images of Cahun’s face are also framed by a brass sun-like band hand painted with flecks of eggshell blue paint. This pointed circumference, while beautiful, is a sharp edge that, like a ninja star, could mark the wearer or cause significant damage if thrown. In both cases, these artworks are not easily consumable wearable items but artworks that experiment with the permissible and political in jewelry contexts.

Edwards’s, Debris Facility’s, and Thomas’s artworks are displayed on clothing, through skin on bodies, on backpacks, on sidewalks and streetscapes, and on the gallery wall. They are simultaneously wearables, keepsakes, objects, and sculpture: activating ideas around anti-capitalist economies and value through material sustainability and experimentation, trade and gift economies, and gender through feminist politics and trans identity.

While aesthetically these artists’ works may appear to share qualities with those of a Lisa Walker neckpiece or a Karl Fritsch ring, they’re very different in material, scale, and proportion. As they attach to a wall or are worn on the body—either inserted through the skin, onto clothing, or hung on a backpack—their individual statements are less operatic. Often they slip between the folds of fabric or are delicately layered in multiple cobwebs across the body. These artworks don’t declare their agenda but infiltrate through cohesion with the body. The subject and the piece simultaneously activate the artwork. These artworks are full of political self-awareness but also humor as they’re carried, infiltrating parasitically between frameworks, between contemporary visual art and jewelry contexts alike.

[1] Adamson discusses this movement in relation to the eponymously titled 2008 New Museum exhibition Unmonumental: The Object in the 21st Century in “Directions and Displacements in Modern Craft,” in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2011: 20–33, Art Association of Australia and New Zealand, 2011, 30.

[2] Adamson discussed this idea in relation to textile artist Anne Wilson’s observations of student Josh Fraugh’s use of technique as a positive form of sloppy craft in “When Craft Gets Sloppy,” in Crafts, no. 211, March–April, 2008: 6.

[3] New York poet Gillian McCain discussed this idea in relation to 1970s punk music and her book (co-authored with Legs McNeil), Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (2006), on The Music Show, Radio National, September 3, 2016.

[4] The Frankenstein Backpack Show featured Clementine Edwards, Brighid Fitzgerald, Ruby Fitzgerald, Debris Facility, Rebecca Thomas, and Isadora Vaughan.