This article examines the work of four jewelry artists who integrate printmaking as a form of drawing, documentation, and dialogue between the two-dimensional and three-dimensional realms. While the summations to follow do not necessarily offer the work justice, says Agabigum, her intention, rather, is to draw upon the similarities of how every artist’s work is connected to printmaking. Each has integrated this discipline into their technical lexicon through the printing and inking of a matrix, built upon intaglio processes.

Intaglio, a method of printing from a matrix, traditionally pulled from a zinc or copper plate with an incised image on the surface, is thought to have originated in Germany during the early to mid-1400s. The intaglio process encompasses various techniques to incise images onto the plate, including engraving, drypoint, mezzotint (a tonal method of printing), aquatint (a form of tonal printing with rosin), and etching. The illustrative nature of intaglio, with its intricate line work and multitonal qualities, led to its rise in popularity. Today, the engraving and etching processes of intaglio are still used in the production of items such as stamps, currency, and legal documents like passports.

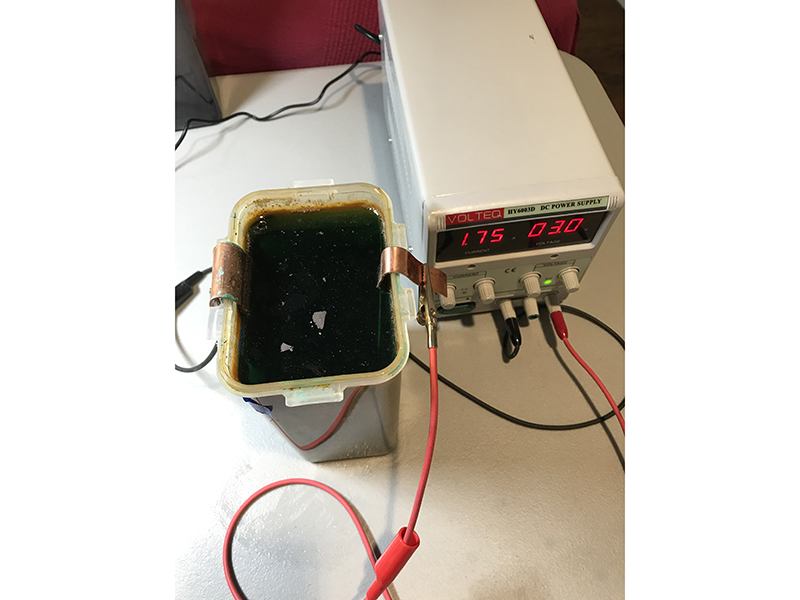

The most common crossover between metalsmithing and intaglio is perhaps engraving and etching. For artist and educator Jim Bové, the process of incorporating print into his work began while teaching etching to students. Bové, who gives workshops on how to etch with more health-friendly processes such as E-etching (also known as electrolytic etching), developed his skills in the actual print process during collaborative workshops that were taught in tandem with a colleague who specialized in printmaking.

Bové’s prints are unique in that they are created from drawings he made while participating in “The Arctic Circle expeditionary residency”[2] in 2019. With limited space aboard the ship the artists were living on, Bové was equipped with only a few items such as his computer, camera, and sketchbook. He also 3D-printed brooch components prior to the trip and brought the prints with him as his portable studio. As one of 29 artists and scientists selected for a 20-day Arctic expedition, he sailed around the Svalbard archipelago, documenting and creating pieces inspired from observing his natural surroundings. As Bové recalls:

The receding glaciers left behind rocks that were ground smooth over the ages. The way some of the glacial till was eroded created beautiful shapes and patterns. During the trip I photographed and sketched the shapes in the rocks that I observed. These rocks were moved by the slow pressure of glaciers. The rocks were shattered, broken into smaller pieces, smoothed and worn down, their shape determined by the massive forces working on them. As the glacier receded, the rocks were left behind to be found in the open.

The archipelago is a protected landmass, which meant Bové and the other artists and scientists were not allowed to take anything off the land as souvenirs, nor leave anything behind as remnants of their presence. Therefore, Bové created 3D-printed brooches that could temporarily capture various rocks and ice chunks found on the archipelago.

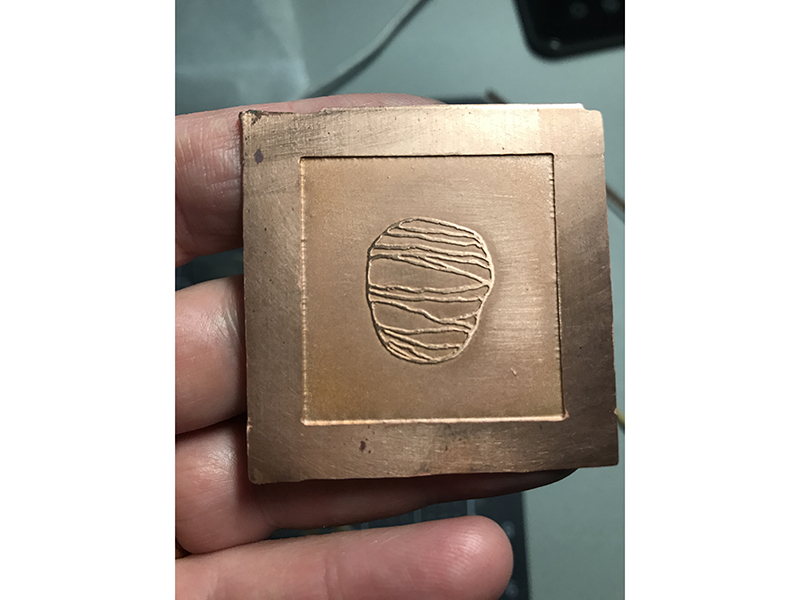

Animated by the intricate glacial till patterns that he was documenting, Bové used his drawings to create etchings on small copper plates. Many of the pieces of glacial till he documented in his sketchbook and camera rolls were also used later as inspirations for his etchings after he returned home.

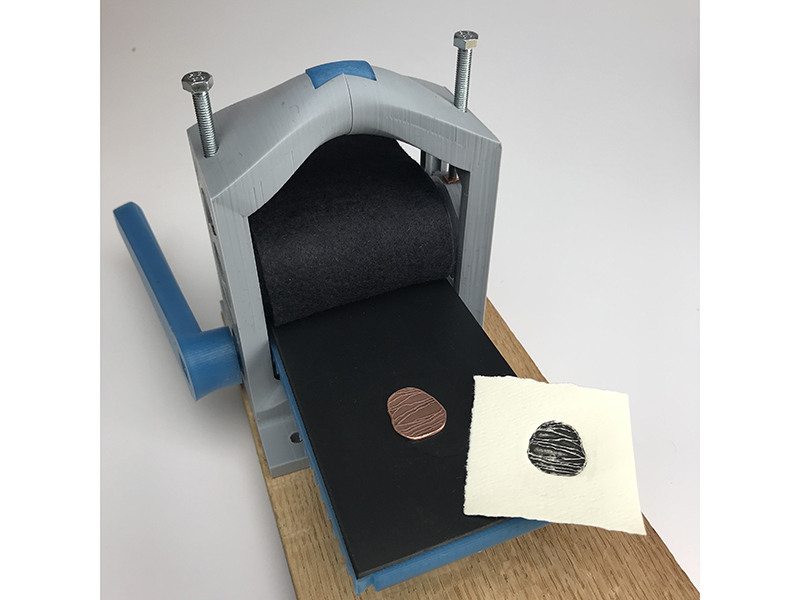

The etchings created from Bové’s drawings and photos while traveling not only act as a means of documentation of the Arctic Circle expedition, but also become tangible remnants of a memory and experience. “The process I use is electrolytic etching in copper,” says Bové. “I paint my drawing on using an oil-based resist, then scratch away at the resist to create the line width and detail I want before etching the image into the metal. The printing press allows me to use heavier paper and create a more traditional, intaglio, look.”

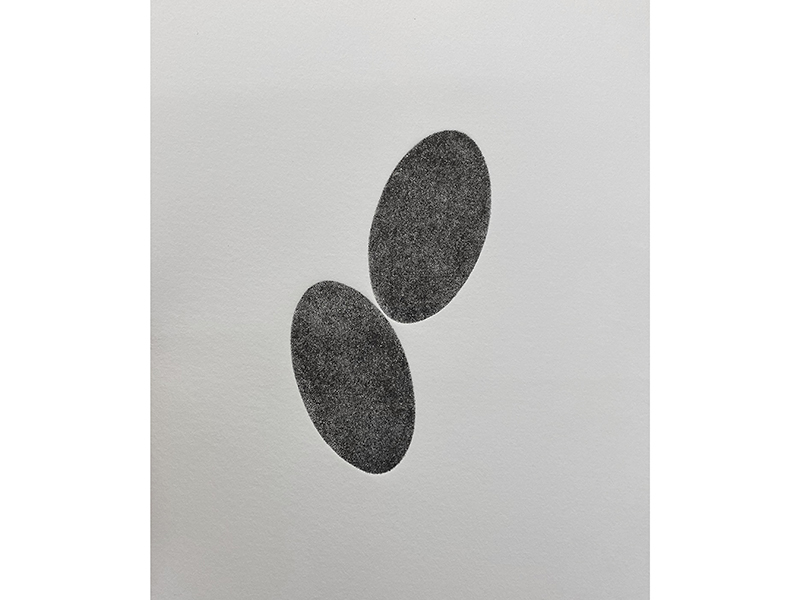

Rather than framing the small, intimate prints from his etchings in traditional frames to solely hang on the wall, Bové turned the prints into jewelry by 3D-printing frames with an integrated magnetic pin back that could be worn on the body. In a sense, they mimic the 3D-printed brooches he made while sailing around the Arctic. As another homage to the 3D printer he used during his residency, the prints themselves, while etched on copper plates, were either hand printed or printed on a printing press that Bové 3D-printed from open-source specs he found online.

The print brooches alter the viewer and wearer’s role within the work. They take the documentation of the intensive glacial changes of the land and rocks from Bové’s drawings and translate them to the body. As glaciers melt and move, they take their surroundings with them, and in a similar manner, the wearable prints in Glacial Till are carried and moved with the wearer to new places.

By continuing to use 3D-printing as a process to physically print the etched plates and then 3D-print the frames/mechanisms to capture the etchings he created when back in his personal studio, Bové adds to the immensely layered meanings behind a body of work that combines printmaking, 3D-printing, and jewelry.

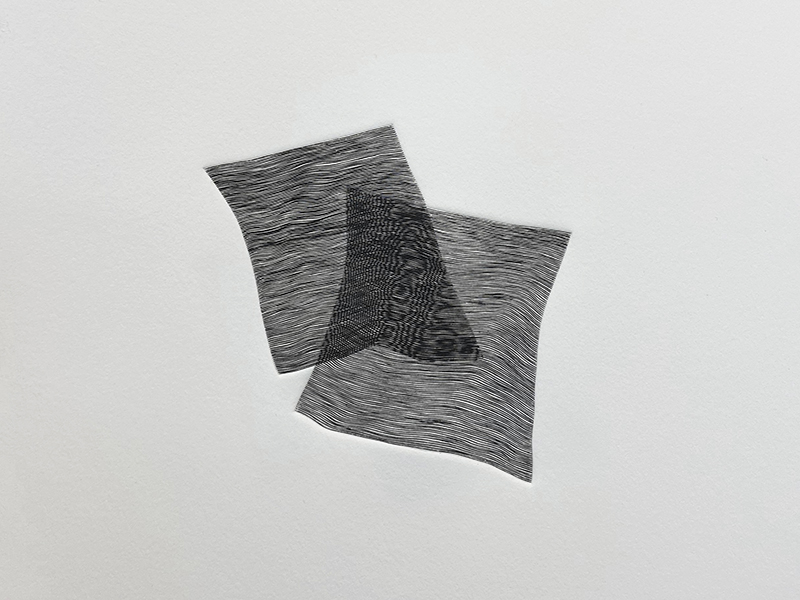

Drawing as a translation of ideas is also a motivational factor in the work of Lynn Batchelder. Provoked by engaging drawing as a way of “thinking, reflecting, exploring, and inventing,” Batchelder melds line and surface in her work through engraving on metal to printing on paper. While Batchelder says she’s not a formally trained printmaker, her works exemplify the controlled hand of a seasoned engraver in the works she produces.

With access to state-of-the-art print studios at locations such as Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, Women’s Studio Workshop, and the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, Batchelder has had the opportunity to intermittently dedicate her focus on mastering printmaking techniques such as engraving in her work.

Rich with textures created from silver etching and hand engraving, her jewelry objects visibly pay homage to the matrix plates used historically in intaglio. While Batchelder’s jewelry is not used as the direct printing matrices, the correlation between the physical objects and her separate body of prints is apparent through the gestural quality of her mark-making.

“Recognizing the crossover between tools and techniques used in both print and in metal, intaglio felt like a seamless extension of my work. The logic that an object can appear drawn, become a drawing, or that a drawing or print can seem tactile or conjure physical sensations, is fascinating,” says Batchelder.

The thin repetition of lines, layered over and over again, brings visual intensity to Batchelder’s works on paper while reflecting back on the dark lines of her sawed steel pendants that play tricks on the eye. The highly detailed lines of Batchelder’s prints draw the viewer in and require the same care and attention as her jewelry. They ask the viewer observing the work to come closer, to note all the quite intentional details embedded onto the paper. The result is an intimate moment where viewers find themselves plunging into the depths created from between the lines.

A recent 2020 MFA graduate and former student of Batchelder’s at SUNY New Paltz, Jamie Scherzer, also found printmaking as a means of integrating the repetitive processes of metalsmithing with the similarly repetitive process of two-dimensional mark making. Says Scherzer:

My second semester at New Paltz I took a paper-making class, which is taught through the printmaking department. I ended up embedding metal into paper and oxidizing the metal and got pulled into the paper/printmaking world. Through the printmaking department there was an opportunity to apply to a printmaking residency in Belgium at Frans Masereel Centrum, which I got accepted to based on my past work and proposal of approaching print from a metalsmith perspective. That was October 2019, so I spent the semester leading up to then exploring the repetitive process I’d been investigating in metal and approaching the metal as a canvas, challenging myself to create dimension on this two-dimensional surface that would in turn create something palpable on the page.

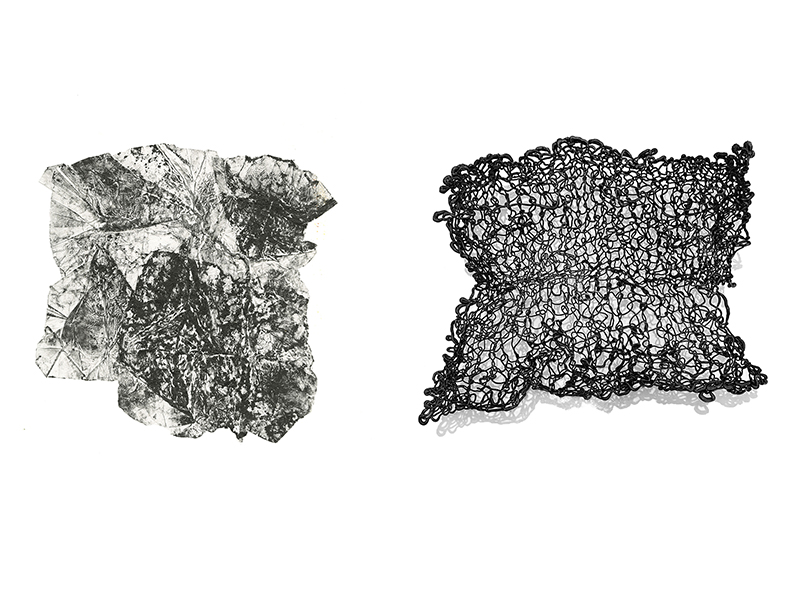

In Scherzer’s work, the plate used for printing is not only treated as a means to print, but is also transformed into an object of display. The artifacts left from inking and printing, made of either silver or copper, were surprising remnants that Scherzer utilized. They became jewelry objects or were shown in conjunction with the prints pulled from them. Welcoming the serendipitous nature of the flattened metal forms after printing, Scherzer states:

I was printing with both copper and silver “plates,” using them as a tool to create imagery, and loved the play between the two mediums and how they would often print in ways not expected and bring out minute details and imperfections from the metal that may have otherwise not been seen. After printmaking I would still have this interesting metal plate which I could either keep as an artifact or turn into jewelry.

Scherzer fabricated necklaces from the plates used in Traces 1 and 2, for example, and turned plates into Empty Box and Release. As three-dimensional outputs of the matrices are warped and deformed through the printing process, the ink gets embedded in the crevices of the metal surface, much like in Batchelder’s work, bringing depth to the spaces created between the positive lines and spots, and the negative spaces of the plates.

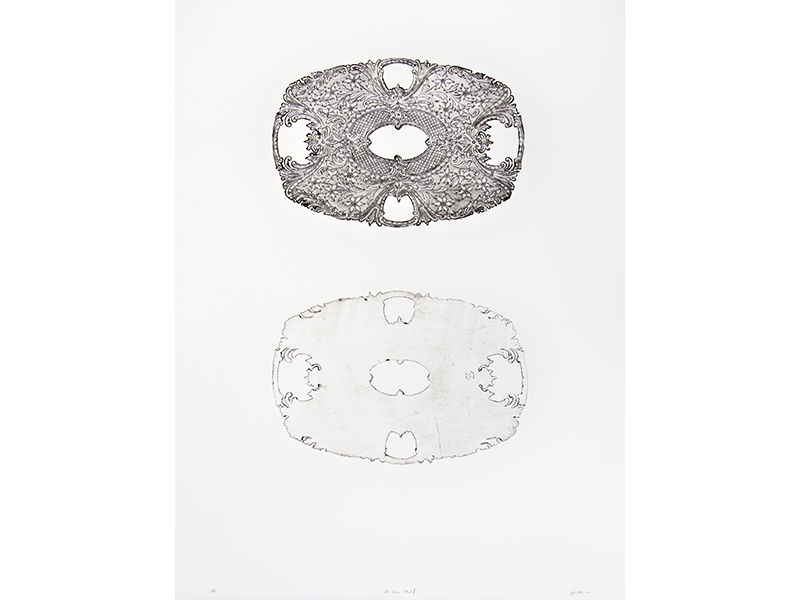

Elevating the printing matrix as more than just a means to an end is also inherent in the works of Jaydan Moore. The matrix of donated silver platters, in this case, is repurposed through printing and then repurposed again into vast sculptural objects that tell stories steeped in history.

Moore, who grew up in Northern California, had been integrating print into his artistic process since his early childhood. As part of his family’s tombstone and marker business, Moore would take rubbings of grave markers. “I loved going out with the carbon paper, laying it down on the granite, and rubbing the surface to reveal the information on top. This process congealed in my mind the notion that we are affected by places and objects that surround us,” says Moore. This process of duplicating information and forms translated into Moore’s work as an adult.

With ink embedded into the incised scratches from natural wear of the platters to the unique surface idiosyncrasies highlighted through the printing process, Moore’s platter prints, like Batchelder’s engravings, show the tiniest of details in the most intimate way. The prints become a permanent documentation that is not mediated in the way a photo would be. Rather, their direct impressions offer the viewer a closer connection to the original object. They become tangible documentations of the original.

The concept of mass production took off in the early 1900s, and the mass production of serving platters has a neat equivalency with the ability printmakers have to take multiple prints from a single printing plate. Both processes build on having an original pattern to pull from, despite the difference in manifestations.

Much as the unique gestural qualities of each printmaker’s hand are documented in the final print, the mass-produced platters that Moore integrates into his work each have unique qualities of ownership imbedded into the metal surfaces through mars, scratches, and dings. The notion that an object undergoes a journey of evolution is similar to Bové’s Glacial Till works, with their stones and the resulting prints from sketches of those stones acting as the documentation of their travels. In Moore’s case, the object and the resulting documentation manifest in his donation project. The printing process offers a means of giving back to his patrons while also cataloguing the platters before integrating them into his sculptural objects.

“I make only two copies; one for the owner of the platter, and one for my archives. This process lets me learn more about the families who lived with these objects and the reasons they are ready to let go of them,” says Moore. “Seeing how the communal idea of what a specific object means to our society and how the individual’s connection to these objects changes that ideal has always excited me. How the value of our objects ebbs and flows as we imbue value and meaning onto them harkens back to the tombstones I used to walk through when I was a child.”

The limited production of Moore’s prints, meanwhile, runs counter to the concept of mass production, and is a seductive component in his process. With the printing process, Moore could pull multiple, if not hundreds, of prints from a single platter. The choice to pull only two prints, one for the family who donated, and one for himself, speaks to Moore’s restraint and the resulting rarity of the “object” created. It creates an intimate shared moment between patron and artist, platter and print.

The connectivity between material and paper, from three-dimensional to two-dimensional, becomes blurred through the three-dimensional nature of printmaking. There is a physicality that speaks to the process. Perhaps it’s the physicality of printing that is so alluring to metalsmiths: the ability to physically alter a plate and see the changes of the surface documented on paper. The plates or matrices respond to the ink, and in return the paper responds through the embossed impressions and tonal depth left on its surface long after printing.

[1] Material Fiction and Capturing a Moment.

[2] http://thearcticcircle.org/program/.