February is Black History Month in the United States. To honor this, all month AJF has been spotlighting articles and videos we’ve previously published about Black makers and/or by Black writers.

The Jewelry||Adjacent series, by Rebekah Frank, has spotlighted two Black artists who use material, techniques, or themes related to jewelry practices. The body is present in their work, not necessarily as the recipient of adornment, but in the importance of the physical body to their form, topic, or narrative. The adjacency of these artists to jewelry provides fresh perspectives to those of us immersed in the field.

DEMETRI BROXTON

The mixed-media artist’s beaded boxing gloves investigate race, masculinity, and sport in the United States. Boxing is an arena where legends are made, teeth-shattering violence is celebrated, and hypermasculinity is normalized. It is also a highly racialized space, where Black men dominate and simultaneously put on display. So why would a bead artist who has never boxed create art about boxing?

Of Louisiana Creole and Filipino heritage, Broxton resides in Oakland, CA. He embellishes boxing gloves with cowrie shells and glass beads. Broxton uses the cultural histories of these materials to draw parallels between history and current culture, positioning his work in the imaginary divide between craft and fine art.

The way Broxton applies the cowrie shells to the surface of the gloves also refers to the Yorùbá tradition of the Ilé Ori. These ritual objects were traditionally covered with cowrie shells—shrines that housed and protected an individual’s head or orí, the seat of a person’s character, behavior, and ultimate life destiny. Broxton’s gloves draw several parallels to these ritual objects: in the material choice, in the appearance of the finished object, and in the way that the gloves protect the boxer’s hands, bringing wealth and prestige if the wearer is successful in the ring, as well as a modicum of protection from white society.

Broxton often titles his pieces with phrases from hip-hop or rap lyrics, beading the text onto the boxing gloves using Czech glass beads. Czech glass beads were introduced as trade goods to the indigenous people of North America and Africa by European colonialists and slave traders, respectively. The new material was quickly absorbed into traditional methods of making in both cases, taking on new meanings within different cultures. Broxton researched how the Yorùbá incorporated beads into their material language, specifically how artisans selected the colors of the beads for the embellishment of clothing, everyday items, and ritual objects.

Read the full article, which brings together so many more fascinating threads than described in this brief summary.

ANGELA HENNESSY

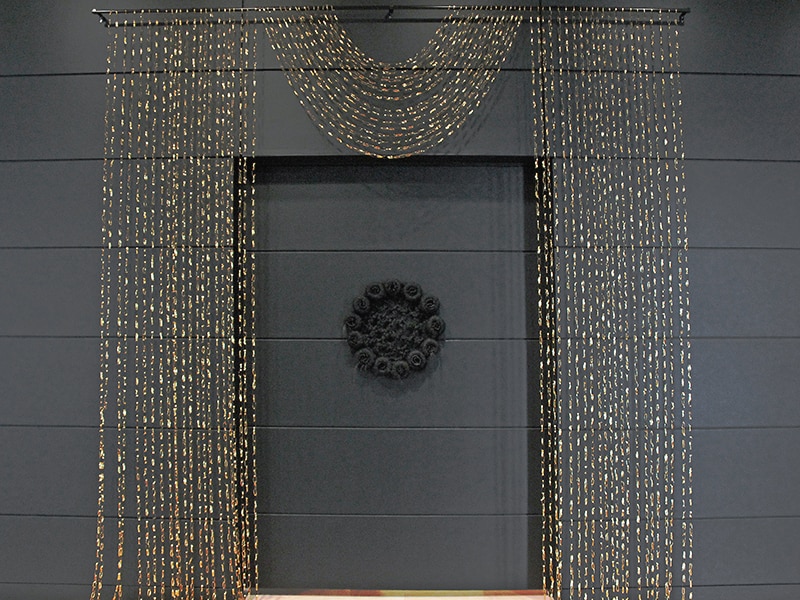

Hennessy uses her practice to process her relationship to grief personally and culturally as a Black, queer woman. In doing so, she creates a place for collective mourning and a space to honor those who came before, where the viewer is invited to consider what grieving means.

Victorian mourning jewelry was an early influence during Hennessy’s graduate studies at California College of Art, rooted in her high school and undergraduate studies in jewelry. Victorian mourning traditions included lockets, lengths of hair braided into bracelets, strands of hair intricately arranged in pendants, and visually complex wreaths adorned with the deceased’s hair as flowers and flourishes surrounding their portrait. The mourning jewelry provided a way to keep a deceased loved one physically present and connected to the living, using their hair to create intimate objects of remembrance.

As Hennessy researched this tradition, she realized that hair had a place in grieving rituals across culture and history. An online search on hair and mourning results in a wide range of bereavement practices. The recently bereaved might shave their heads (Nigeria), not shave their facial hair (Greece), not comb or groom their hair (Philippines), keep a lock of hair for a year (Lakota), or use their hair to cover their face (Ancient Egypt). What fascinated Hennessy in this variety is “how hair became the material that connected one to the dead, while marking the separation caused by death.”

Hennessy’s personal experience provides a narrative that threads through her work. The absence and discovery of family connections, the struggle of defining oneself when embodying multiple identities, the finality of a parent’s death, a near-death experience, the weight of ancestral grief coupled with the continuation of violence against Black bodies today, the requisite grieving of being Black in America. Through her creative research, she holds space to experience the beauty and anger, joy and sorrow, that can exist simultaneously.

Read the full article, which—among other things—explores Hennessy’s practice, the whiteness of the art world, and the politics of hair