1. What is post-studio?

Jewelry has its own particular history as a studio craft. The tools used and the specific ways of making—skills, knowledge, and materials—stretch back hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years. As art jewelry developed in the 20th century, many of these traditions were challenged. But throughout, the studio remained the principle domain of jewelry practice.

In the early 21st century, we witness the potential for an expanded field of jewelry practice, one following established trends in the wider field of art practice. This includes an embrace of the so-called social, or relational, turn. This emerging form of jewelry practice exists (predominantly) outside the bounds of the studio environment.

Although he did not invent the term, the concept of “post-studio” has become synonymous with the artist Daniel Buren, who published an article on the historical and contemporary function of the studio in 1971.[1] Here was a manifesto that rejected the rigidity of the studio as the dominant space of art production, and reflected the developing practices of artists involved with the contemporary Conceptual Art movement. One such artist was John Baldessari, who had himself begun teaching a course he called Post Studio Art, at Cal Arts in 1970. Here, classes would involve the exploration, engagement, and capturing of everyday life.[2] Outcomes could include photographs, assemblages, upcycled consumer items, and video documentation.

The idea of a post-studio jewelry practice is established by Mònica Gaspar. In discussing After Wearing: A History of Gestures, Actions, and Jewelry, the 2015 exhibition she curated with Damian Skinner, Gaspar suggests “these projects seemed to belong to the kind of post-studio practices that had emerged since the 1970s.”[3]

Post-studio practice evokes a range of methodologies distinct from the traditions of studio craft. It offers a lens by which to better articulate a practitioner’s perspective. We might consider the idea of post-studio practice as shifting one’s focus from the interior of a private space outward, and into the world.

Such work, both in jewelry and wider art practice, is often recognizable by a focus on engagement with a public audience. It encourages participation, and frequently collaboration. Such practices often occur in public spaces. Outcomes are interventions of the urban domain as much as the creation of wearable artefacts. Such projects have helped expand and transform our understanding of jewelry, and created an engagement between art jewelers and the wider social world.

Such work can be extremely diverse. For example, Liesbet Bussche utilizes and subverts the language of jewelry in creating oversized jewels as public sculptures, such as with Urban Jewelry, (2009). Meanwhile, Mah Rana, in her project Meanings and Attachments (2001–ongoing), undertakes subject interviews to understand their relationships with the jewelry, and communicates these through photography. Gabriel Craig’s jewelry practice becomes a kind of performance, with Craig literally repositioning his studio bench in a public urban setting (The Pro Bono Jeweler, 2010). Jewelry practice in the public realm has also been significantly explored and documented in the research project led by Elizabeth Holder and Gabi Schillig, Schmuck als Urbaner Prozess: Artistic Interventions in Urban Space: Documentation of a Research Project (2015). Here the city and urban space was both the site of inspiration to draw upon as well as the site of various interventions, performances, and public engagements. Most recently, Claire McArdle’s project Walk (2021) brought the studio into the public domain, whereby “the act of making is taken to the streets in a performative walking exploration of tool use in the contemporary jewellery and object field.”[4]

This form of art jewelry practice has been well documented.[5] Yet while such critique provides adequate exposition of the context and relative merit of such work, less attention has so far been paid to the distinct modes by which such work is made. What are the specific methodologies and practices by which participatory and relational work is made? Besides an understanding of the work itself, from a practitioner’s perspective little has thus far been proposed as to how “participatory” or “social” projects are “made.” Given the significant and extensive writing on making within craft studio practice, it seems timely to begin to address this relative lack of discourse about those forms of jewelry practice that exist outside the tradition and conventions of the studio.

Once settled on this focus toward practice, we can consider the specific tools and methods and/or actions that may be used in such projects. One such action, the value of which is recognized by practitioners themselves, yet barely discussed in the literature on art jewelry, is the role of walking.

2. Why walking?

With many post-studio projects involved in forms of spatial practice—in which the location of the practice is intrinsic to its production—I would argue that walking forms a key methodology for such work. Walking is frequently the action and the glue by which various projects come together. Walking may contribute much to the understanding of a project. Yet it remains neglected or unaccounted for in the writing and documentation of such projects.

Walking holds a strong position in critical and social theory. Walter Benjamin explained the concept of the flâneur within his historiographies of Paris and London. More recently, Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life, and his articulation of walking as a tactical response to the governmentality of urban space, has proved influential. Perhaps invoking the Surrealists, de Certeau suggests urban planning as a restriction on mobility. Walking is best suited to overcoming this restriction, via jaywalking, fence-jumping, and other negations of the rules of general travel.

Walking also has an already established history within art practice. Extending back to the Surrealists of the 1930s through the initial era of post-studio art practice of the 1960s and 70s (notably Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking), walking remains a notable action within contemporary art practice.

For an account of walking’s significance to both life and art, Rebecca Solnit’s Wanderlust is comprehensive. Solnit states that walking offers “a kind of syntax organising thought, emotion and encounter,”[6] providing a means by which to know the world “through the body and the body through the world.”[7] Hence, we may understand walking as a methodology by which certain forms of practice unfold. If we are to refer to jewelry practice as participatory, social, or relational, we should enquire as to the manner by which these situations arise and are actioned. Although it is not the only aspect of such projects, I suggest that walking plays a significant role in the making, and meaning-making, for many art jewelry projects.

I consider this “critical walking.” I use this term to connect it with the concepts of critical thinking and critical making, both means by which to connect mind and body in an integrated process and to evoke various processes of engagement, enquiry, and analysis. I suggest that through critical walking we may engage with the world and our place in it—with the multilayered aspects of geography and history, the political, the social, and the cultural. Critical walking may allow us to tease out lost, hidden, or forgotten narratives, and provide encounters that move us affectively, emotionally, and psychologically.

Walking presents us with a unique experience for engaging with the world, if we choose to embrace it. Walking offers us a way of being in the world that, when it becomes “critical,” allows us to become cognizant of our body, our actions, and our identity, of our place in and of the world, and of the world itself. Many of these themes can be identified in the practices and projects of a range of art jewelry projects.

3. Walking and art jewelry

To help demonstrate the relevance of the above themes within art jewelry, and the way in which walking facilitates these, I return to some well-known artists and projects, previously well-discussed except for the role of walking within them.

Yuka Oyama

Yuka Oyama is a veteran of many diverse relational projects, including Berlin Flowers (2007), an installation on the balconies of a Berlin housing estate in which 500 participants were involved, and Schmuck Quickies (2002–2012), where Oyama made pieces of jewelry spontaneously and directly upon the bodies of participating strangers.

Oyama describes a more recent project, Helpers: Changing Homes (H:CH), from 2018, as one “that investigates the multifarious definitions of homes and how objects help to make a place a home, especially for those whose lives are nomadic or frequently uprooted.”[8]

H:CH involves sculpture, performance, film, and more conventional jewelry, but the most well-documented and discussed aspect of the project is arguably the public procession of the large-scale sculptures, worn on the streets of Wellington, New Zealand. However, little of the specific role walking plays in the meaning-making of this dynamic and engaging event has been discussed, even though Oyama herself recognizes its importance.

Oyama refers to her life-sized, critical costumes as “person-thing-hybrids.” They investigate “how to constitute a sense of home for people who constantly move around.”[9] It is an interesting point that these are considered works of jewelry at all, but this only further highlights the breadth of both practices and outcomes that constitute art jewelry. Within this project the sculptures are only one aspect of an integrated whole, which also includes more conventional jewelry objects.

Migration, life as a refugee, and issues of homelessness are evoked, not least in relation to the materiality of these sculptures, which are made of cardboard boxes. The material aspect of this project has been discussed elsewhere,[10] but to overly focus on this does a disservice to the performative aspects. Oyama’s performances correspond directly to de Certeau’s notion of walking as a spatial acting-out of place.[11] Given the themes, walking is an important device in articulating these concepts, as opposed to viewing the sculpture in a gallery context. Oyama herself states how “walking has helped to communicate this aspect for me to the audience.”[12]

Walking is therefore part of the action of the work, and it also helps us find meaning within it. These dualities combine when we consider further issues at play. For Oyama, the work considers and explores “the disconnections often felt in contemporary life: the degeneration of human-to-human emotional communication and an increasingly eroded sense of belonging.”[13] Oyama speaks of how the act of walking facilitated artistic expression within the participants, and how that resulted in a shared collective bond. Oyama’s sculptures facilitate this experience, but only through the act of walking can this transformation in consciousness emerge, along with a true understanding of the work.

Jacqui Chan

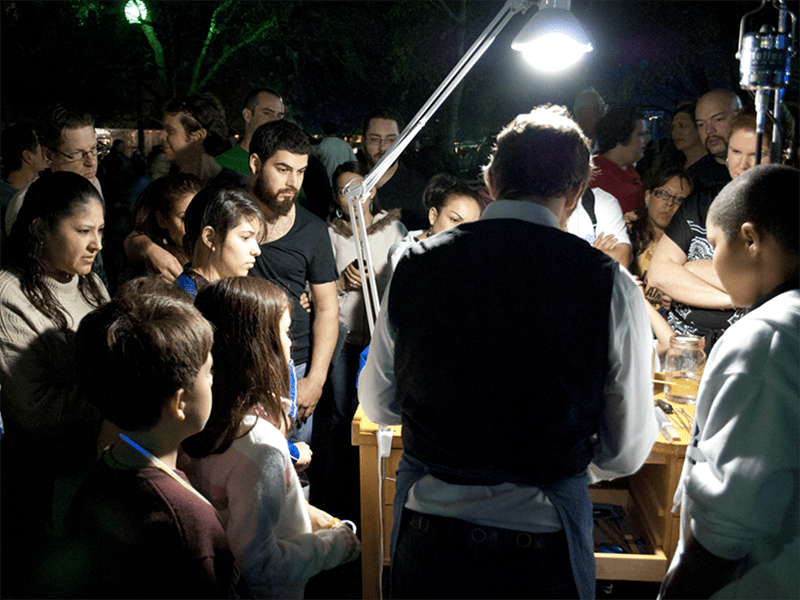

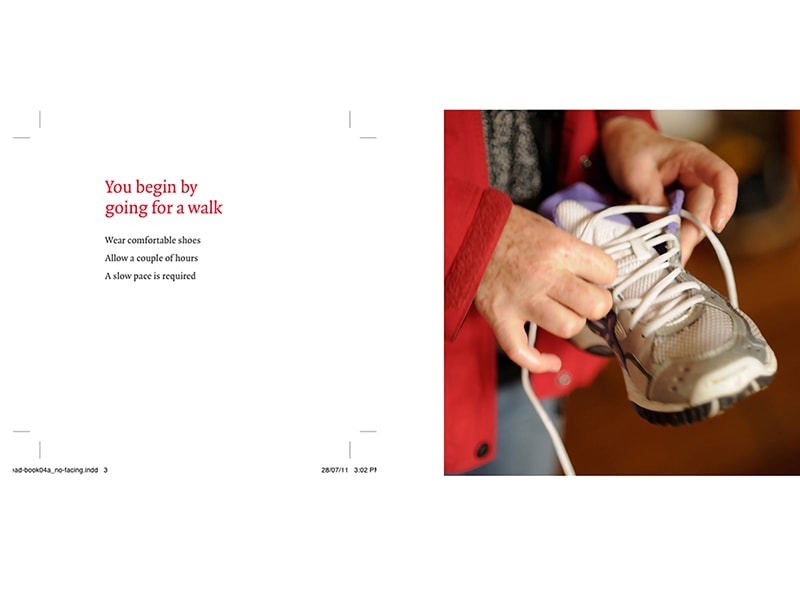

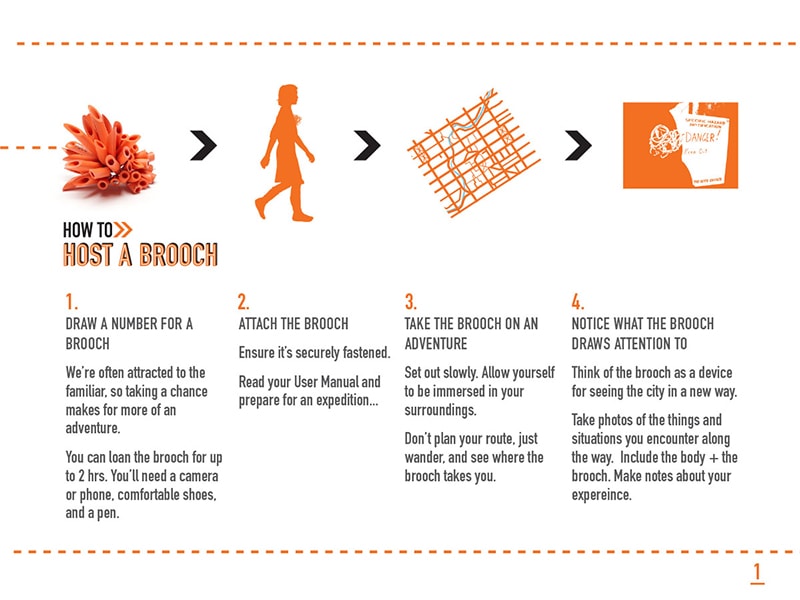

The importance of walking is further demonstrated in Jacqui Chan’s “Host a Brooch” project, from 2011. In collaboration with Caroline Billing of The National gallery, “Host a Brooch” offered a public still traumatized by a recent earthquake in New Zealand an invitation to reconnect with the city through an urban jewelry adventure. The goal was to “produce new experiences and connections between wearers and their urban surroundings in post-earthquake Christchurch.”[14]

“Sixteen brooches were created by Jacqui Chan from materials gathered around Christchurch. Members of the public were then invited to ‘host a brooch’ on an excursion around the city for two hours… The key question they had to answer was ‘how did the brooch alter your experience of the city?’ Their adventures and thoughts were displayed in the container, with selections published in this catalogue.”[15]

Billing said that “Just as a bicycle alters our experience of a city, the brooches produce new sensory experiences, routes, and encounters, (re)connecting us with our surroundings.”[16] The brooch here acts as both a talisman and a lens. Both features are at play in providing permission to interact with and rediscover the city through the act of walking.

Walking, that usually mundane act, is now undertaken with a heightened consciousness as the participant’s embodied engagement with the urban landscapes produces visceral emotions within the wearer. Some of these are described on the “Host a Brooch” blog:

“While some participants felt grounded, for others the experience stirred heavier feelings of sadness, grief and vulnerability, as their brooches drew them for the first time towards scenes of destruction… One woman arrived excited to host a brooch, anticipating a lighthearted fun experience. However she was shocked to find her walk deeply moving and almost overwhelming: she returned after just half an hour.”[17]

While we must recognize the importance of the brooches themselves, without which the project would not exist, we can equally reflect upon the act of walking in facilitating our experiences of the city. While walking, the city and its histories, our memories of it, and its ever-changing atmospheres are all invoked and experienced.

Roseanne Bartley

Perhaps the artist who most thoroughly integrates walking within an art jewelry practice is Roseanne Bartley, who through many projects has made walking a specific focus, indeed methodology, of her making.

Such projects include the My Shadow Wears series (2013 and 2016), Postcards from the Ring Road (2015), and the ongoing Seeding the Cloud (2010–), which has the subtitle “a walking work in process.”[18] The prominence of walking is further emphasized in her description for Postcards, which begins: “In a series of public walks, the technique of brooch-broaching became a tool through which to speculate on the origin story of jewellery.”[19] Here the act of walking facilitates an act of narration from Bartley and a discussion amongst her and her participants: describing how archaeologists recently discovered the oldest remnants of a bead-like form in South Africa, Bartley invites participants to hypothesize what came first—string or bead.

The subversive and political potential of walking is humorously noted. When Bartley and her participants pause for discussion in an unspecified foyer or shopping mall, they are promptly told to move on. “We’re not given a specific reason for our ejection,” writes Bartley, “but initial advice is that what we are doing is out of the ordinary, and requires centre management permission.”[20] In this case, not walking is as loaded an act as walking itself, a truism that would have no doubt been supported by the Situationist International.

Bartley consistently employs walking as a method through which to engage with the urban environment, but it is also fundamental to physical acts of making work.

Bartley describes Seeding the Cloud, for instance, as involving “walking, sorting, drilling, and threading.”[21] As participants walk, eyes to the ground, materials are gathered. These findings are then transformed into wearable objects at temporary workstations provided by public architecture such as park benches. The whole process is an outing threaded through by the string of walking.

The symbiosis of walking, jewelry, and the urban environment is perhaps most integrated in the project My Shadow Wears. In it, jewelry is “produced” directly through the act of walking, by allowing found detritus to become positioned on the body’s street-cast shadow.[22] Transitory and ephemeral works made possible only by the physical act of literally walking into them, they are captured in photographs.

In Bartley’s projects, emphasis is always placed on the role of walking. These projects seem to achieve lift-off with the initial act of walking, whether either by Bartley alone or with participants. Walking is the journey on which all experiences fold together to create meaning, and while these experiences may become manifest in physical objects, it could be said that the true value of the project is located in the memories of these walking encounters.

4. Articulating walking—a role for writing

If we confirm the importance of walking within an emergent practice of post-studio jewelry, we must then consider how the intricacies and idiosyncrasies of this method may be best communicated.

It is perhaps no coincidence that post-studio jewelry practices have developed in parallel with technological advances. The synchronous developments of smartphones, blogs, YouTube, Instagram, and personal websites have all helped facilitate the communication of post-studio projects where the object may only be part of a much bigger project.

Such tools undoubtedly enable both archiving capabilities as well as engagement from an audience that’s absent. Yet images, and even video, can be deficient in communicating an event’s true experience of being and time-of-duration—of being at, or part of, an event that envelops you so totally that your experience of time itself is affected.

Here I propose writing’s great potential. Firsthand accounts, such as Bartley’s, and the inclusion of participant experiences, like those featured on the “Host a Brooch” blog, can be as equally powerful, and as important, as the work itself. Or rather, we should begin to consider the potential for writing to be as much a part of the work as the event itself. Writing at its best, such as in Bartley’s examples, is both eloquently and evocatively descriptive. First-person accounts provide both the psychology and context of each project. And writing is especially relevant in the context of walking-based projects, because the rhythm of prose can so effectively mimic the meter of walking and motion.

Psychogeographer Tina Richardson remarks on how writing is analogous to walking. The mind and the pen follow in the footsteps of the physical step, “handsteps” perhaps, elevating walking to a new level of consciousness.[23] This is true of Bartley’s writing, which is visually and affectively rich. It allows the reader to walk with her, in her very footsteps, and experience that least tangible of experiences: thought.

Describing events for Postcards from the Ring Road, Bartley writes: “Intuitively we form a procession; in single file our pace is meandering. Even though I’ve taken the bookings I haven’t fully planned our route. Our way forward is chartered according to the nearest available light source.” And then, “I guide co-elaborators down a scaffold-covered side alleyway. It’s dark, dusty and smells of urine, and I am quietly thrilled by the theatrics of the space.”[24]

Bartley manages to put you there, in the event itself and inside her head, threads of dialogue woven together as she moves through the city. She gives descriptions of plans and preparations, actualities, even imagined discussions with cited authors from her thesis.

The psychology of walking is often to the fore: “The day began as it often does, with me going for a walk. I had no reliable sense of where I was, or much of a plan for what I was going to do. … I was feeling at a loose end. I stepped out the door filled with an anticipation of opportunity that comes with a life that is ‘not fully joined up, not fully articulated’ I allow myself to meander, weave in and out of the flow of foot traffic.”[25]

Finally, the actions of the walk itself, here somewhat evocative of that psychogeography mainstay: the dérive.

“Veering and pitching forward I project my silhouette towards debris on the ground, aligning material residue in relation to silhouette as if it were an ornament or jewel. My effort to broach and simultaneously index a brooch is recorded on the screen of my smartphone. Holding my hands slightly forward in front of me I continued the process, framing the alignment of cast shadow with debris-ornament with the screen of my phone.”[26]

Like author Ian Sinclair, who has similarly written of ring-road walking excursions, Bartley too employs descriptive and lyrical prose. Like Sinclair, Bartley is able to peel back onion-like layers, to reveal the history of places and something of what it is like to live in a contemporary urban metropolis. Like Sinclair, Bartley’s writing does more than simply document an action or a task. Bartley’s writing unites the mind and body and presents the lived experience of being in the world. We may feel the warmth of the sun, sometimes encounter the smell of the street, and always something of the atmosphere and the rhythm of the walk itself.

5. Conclusion

Post-studio practice is still an emerging form of art jewelry practice. It has however, already produced works to be considered classics of their kind. Their themes have been oft discussed, the outcomes well documented. Yet something of the process, the practice of making such works, has yet to be fully articulated. All post-studio projects have their own methodology, walking by no means the only one. But by focusing some attention on walking here, I hope to promote discussion on post-studio methodologies more generally in the future.

[1] Daniel Buren, “The Function of the Studio,” in October, Cambridge, Fall 1979, n° 10, p. 51–58.

[2] https://www.sfmoma.org/read/open-studio-john-baldessari/.

[3] Andrea DiNoto, “In the Realm of ‘Relationality,’” Art Jewelry Forum, (3 Nov 2015).

[4] https://www.radiantpavilion.com.au/listing/walk/.

[5] See for instance Contemporary Jewelry in Perspective, edited by Damian Skinner, and Liesbeth den Besten’s On Jewellery. Both identify and discuss this development as part of the continuum of art jewelry history. Benjamin Lignel’s article “Made Together: Thrills and Pangs of Participatory Jewelry” (https://artjewelryforum.org/articles/made-together-thrills-and-pangs-of-participatory-jewelry/) provides an acute analysis of participatory practice in the jewelry context. Lignel, drawing upon the precedent of Claire Bishop, casts a critical eye on a range of well-known participatory projects, and notes Skinner’s and Mònica Gaspar’s suggestion that “these projects reject the question of what jewelry is, in favor of what jewelry does.”

[6] Rebecca Solnit, Wanderlust: A History of Walking (London: Granta, 2014), 191.

[7] Solnit, Wanderlust, 29.

[9] Yuka Oyama, personal correspondence, September 26, 2021.

[10] https://dowse.org.nz/news/blog/2018/sian-van-dyk-discusses-helpers-changing-homes.

[11] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011).

[12] Yuka Oyama, personal correspondence, September 26, 2021.

[13] Yuka Oyama, artist statement, https://yukaoyama.com/artist-statement/.

[14] https://www.joyaviva.net/artists/new-zealand/jacqui-chan/.

[15] From the exhibition catalog: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/1242573.

[16] Caroline Billing, https://www.indesignlive.com/projects/host-a-brooch-urban-jewellery-project.

[17] http://hostabrooch.blogspot.com/.

[18] https://www.roseannebartley.com/#/seedingthecloud/.

[19] https://www.roseannebartley.com/#/postcards-from-the-ring-road/.

[20] https://www.roseannebartley.com/#/postcards-from-the-ring-road/.

[21] https://www.roseannebartley.com/#/seedingthecloud/.

[22] https://www.roseannebartley.com/#/myshadowwears/.

[23] Richardson, Tina, “Memory, Historicity, Time,” in Walking Inside Out: Contemporary British Psychogeography, ed. Tina Richardson (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

[24] Roseanne Bartley, Facilimaking Ornamental Events – makeshift co-elaborations of jewellery juh – oul – lurh – ree, PhD dissertation, (RMIT, 2018), 25.

[25] Bartley, Facilimaking, 27.

[26] Bartley, ibid.