Contemporary jewelry practice in South Africa is experiencing a revival, as artists draw inspiration from the country’s rich natural, cultural, social, and political landscapes. South Africa, often referred to as the “Rainbow Nation” due to its diverse racial and ethnic groups, celebrates its cultural variety in all forms of art. Recently, efforts have been made to address the limited exposure South African contemporary jewelry artists face as they strive to establish their unique style in the post-apartheid era. This article explores key aspects of how South African contemporary jewelers have successfully crafted this distinct design identity.

Origins of South African Contemporary Jewelry

To understand the current approach to contemporary jewelry in South Africa, it’s crucial to consider its historical development. Before the 1970s, there was limited documentation[1] available regarding the practice of contemporary jewelry in South Africa. However, it’s noteworthy that the inception of contemporary jewelry in South Africa was largely initiated by skilled immigrants. These goldsmiths, primarily from countries like Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Austria, arrived in South Africa during the 1950s to seek adventure and establish their jewelry workshops.[2] Most of these workshops catered to the commercial jewelry industry, which had been well-established in South Africa since the 1900s, driven by the country’s gold, platinum, diamond, and precious and semi-precious stone reserves. Some of these South African jewelry companies include Charles Greig (established in 1899), A Sidersky & Son (established in 1902), and Jack Friedman (established in 1933).[3]

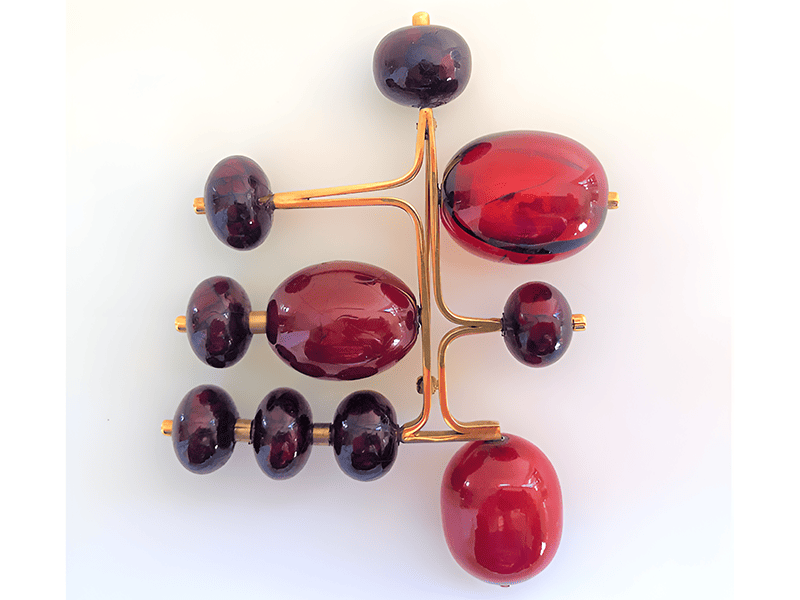

Experimental works in various materials started appearing in South Africa during the late 20th century. These included works from the immigrant goldsmiths such as Erich Frey, Else Wongtschowski, Dieter Dill, Kurt Jobst, Egon Guenther, Eone de Wet, Mauro Pagliari, Margaret Richardson, Maia Holm, and Frida Blumenberg.[4]

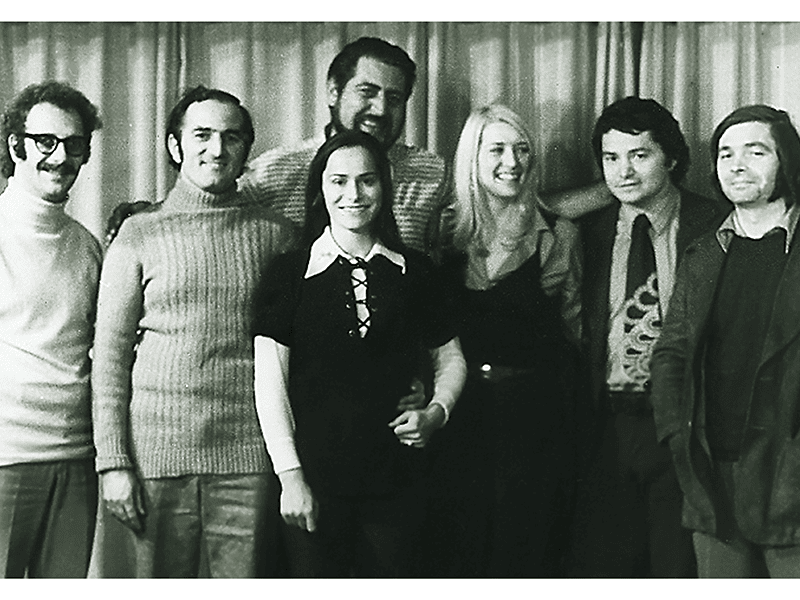

The early 1970s marked a significant period in the history of contemporary jewelry in South Africa and can be referred to as its “golden age,” albeit a brief one. This was mainly the result of the establishment in 1973 of the Goldsmiths Guild of South Africa, in Johannesburg, by a group of South African goldsmiths, led by Peter Cullman. Notably, all the founders possessed extensive training and qualifications obtained from prestigious overseas institutions, such as Pforzheim, in Germany.[5]

The objective of the guild was to promote South African contemporary jewelry through national and international exhibitions, to raise awareness of contemporary jewelry practice in South Africa, and to foster the exchange of information regarding innovative designs and techniques applied in this field.[6] Despite its initial success and ambitious mission, the guild encountered challenges in the late 1980s that eventually led to its discontinuation. The primary reasons for this decline were a lack of government support and the prevailing political instability during that period. This instability brought about issues such as rises in theft and violent crimes, prompting several guild members to emigrate, further contributing to the organization’s loss of momentum.[7]

Many of the guild members developed training programs to address the need for more skilled jewelers and to stimulate the growth of the jewelry industry. Private and tertiary institutions contributed to an increase in locally made jewelry pieces, as well as the emergence of contemporary jewelry designs. Presently, South Africa boasts seven tertiary institutions offering jewelry training courses:

- Durban University of Technology

- Central University of Technology (offering multi-skilled qualifications in jewelry)

- Tshwane University of Technology

- University of Johannesburg

- University of Stellenbosch

- Cape Peninsula University of Technology

- Ruth Prowse School of Art

In addition, numerous Further Education and Training colleges, beneficiation projects that seek to promote the creation of employment and diversification of the economy, and incubators have all emerged as valuable alternatives to universities for jewelry skills development and training across the country.

Many of today’s South African contemporary jewelers are products of the country’s tertiary training institutions. The first local generation of South African contemporary jewelers, most of whom graduated during the 1980s, include Errico Cassar, Verna Jooste, Liz Loubser, Kitty Schneider, Marchand van Tonder, Chris de Beer, Carine Terreblanche, Beverley Price, John Skotnes, and Nanette Veldsman. This group of artists began to, perhaps subconsciously, shift away from a predominantly Eurocentric aesthetic in their work. Subsequently, they can be seen as the pioneers who embarked on a journey to develop a more distinctive South African design identity, focusing (though not exclusively) on translating local cultural motifs, naturalistic motifs, traditional crafts, personal narratives, and social comments in their work. Some of them—Terreblanche, Veldsman, and de Beer, for example—went on to themselves teach.

Cultural Motifs

From as early as the 1950s, South African jewelers applied various motifs, mainly derived from cave paintings, from the indigenous tribes known as the Khoi and the San. These motifs were interpreted from a Eurocentric modernist approach to create the first identifiably South African jewelry. This type of jewelry became known as safari jewelry, and pieces showcased a very literal interpretation of the inspiration.[8] However, this type of jewelry was intended more for tourists wanting to take home a souvenir of their South African experience.

Today, South African contemporary jewelry continues to incorporate cultural motifs. For instance, one of South Africa’s leading contemporary artists, Beverley Price, subtly integrates textures like chevrons and dots in her neckpiece, Mapungubwe Re-mined. These elements serve as subtle references to the scarification patterns seen on the bodies of BaLemba women, who were part of the original culture discovered in the initial excavation site of Mapungubwe.[9]

In contrast, Khanya Mthethwa takes a more personal approach to interpreting South African cultural motifs, using the image of a cow in her latest works.[10] In the collection Echoes of the Past, Mthethwa seeks to confront the effects of colonialism by using symbolic elements like cow skulls to defy erasure and to celebrate the role of the female figure. Mthethwa’s artistic vision centers on the reclamation and celebration of indigenous narratives, achieved by blending her Zulu heritage with ancient Greek symbolism, drawing inspiration from Greek gods and goddesses whose statues were historically important forms of cultural documentation. This reinterpretation gives rise to a fresh narrative while remaining rooted in the same cultural context.

Naturalistic Motifs

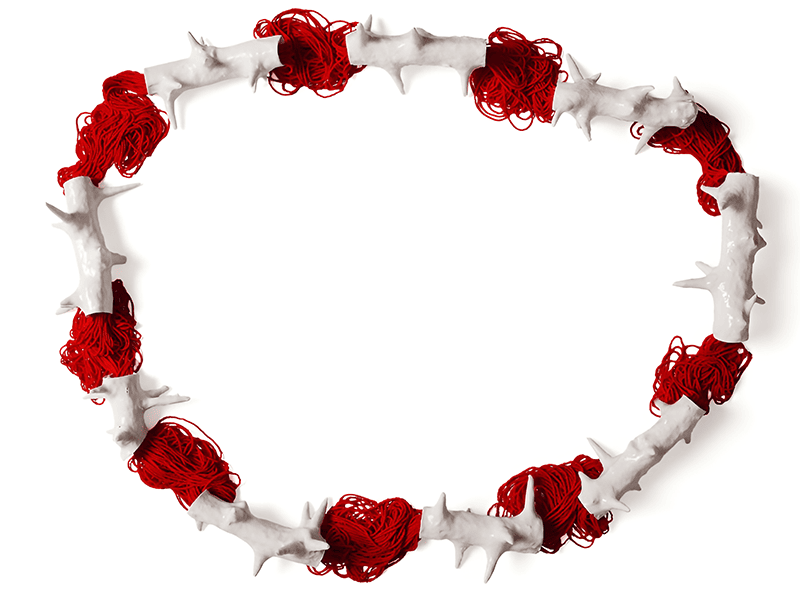

Local contemporary jewelry artists have incorporated various botanical and wildlife themes since the 1950s, drawing inspiration and materials from the rich natural offerings of South Africa. This trend continues today. However, the way these motifs are expressed has evolved, sometimes taking on metaphorical interpretations. For instance, Marlene de Beer uses porcelain thorn tree branches in her neckpieces, titled Thicker than Water, In Sickness and in Health, and Until Death Us Do Part. The thorny branches symbolize aspects of family and married life.

Another example of botanical influence can be seen in the work of Liz Loubser, who meticulously reproduces the indigenous fire sticks plant (Euphorbia tirucalli) as metal brooches. Loubser’s motivation stems from her fascination with biomimicry, and she uses her passion for plants and handcrafted jewelry to explore these concepts. She explains, “I tried to copy the plant exactly, and it became a very intimate process of really getting to know both the plant and my material.” Consequently, indigenous flora becomes an integral component of exploration, with specific jewelry techniques carefully chosen to achieve a realistic representation of the plant.

Crafts

Crafts appear to be the paradigm South African contemporary jewelry is most closely associated with in terms of the techniques and materials used. In the initial years following the end of apartheid, many contemporary jewelers, much like the early immigrant goldsmiths, drew inspiration from indigenous crafts to shape the elusive “South African” identity in their creations. However, in the present day, indigenous crafts serve as a point of reference and are reinterpreted alongside other motifs and personal experiences.

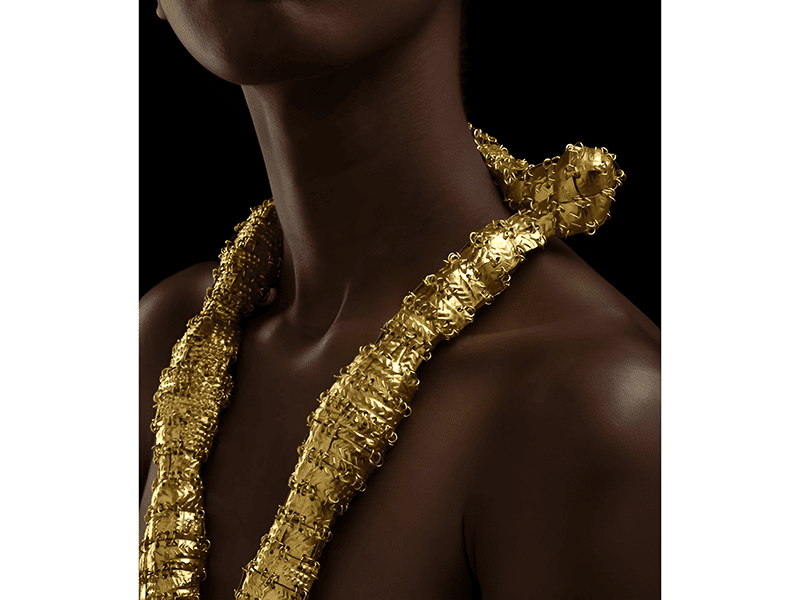

Sam Vincent’s neckpiece, titled Gathered, serves as an example of South African crafts redefined within contemporary jewelry. Traditional Zulu beadwork, which customarily communicates identity and social status, was incorporated into the design. Vincent applied this craft to interpret the theme of a competition, #Hope, and explains that hope can “be ‘gathered’ from the past, present, and future, and is a vital concept that ensures meaning in our lives.” Vincent also highlights the idea of connections occurring through communication, thereby highlighting commonalities.

Vincent’s intention reflects a distinctive approach by substituting traditional Zulu bead motifs with PC motherboard patterns. Through this, Vincent demonstrates how crafts can be reinterpreted in contemporary jewelry when the validity, meaning, and properties of the materials are explored and redefined. (Vincent’s university lecturers were Chris and Marlene de Beer).

Personal Narratives and Social Comments

Any form of political commentary and social criticism was censored during the apartheid era. With South Africa’s new democracy, artists now have the freedom to question various aspects of the state. In the brooch titled First World Problems, Eric Loubser comments on the issues faced in South Africa and Africa compared to developed countries. The brooch is about the Kongolese Nkisi figures, carved wooden statuettes that contain powerful substances in the center, into which iron nails are driven to release that spiritual power/protection.[11] The brooch symbolizes the impact of colonialism, with European objects inserted into the wood reflecting the question of whether Africa would be better off without European colonization.

The polluted pond on the brooch’s back represents how adopting Western lifestyles has led to problems like pollution, prompting consideration of how Africa might differ without colonization. (Loubser was taught by Carine Terreblanche at the University of Stellenbosch.)

Artists can also now more freely express social commentary through their work. Chris de Beer reflects on his spirituality and questions the precious materials associated with various religious artifacts in his work titled Brooches for the Week. The religious artifacts are made from mundane materials such as cardboard from cereal boxes, plastic from milk bottles, cotton thread, steel safety pins, and metallic foil.

Conclusion

While making a living as a contemporary jeweler can be challenging, the abundance of local inspiration, materials, and techniques has inspired the work of a small group of South African jewelry artists who are carving a name for themselves locally and internationally. As our international contemporaries are aware, this is no easy feat. Neither is creating a unique identity in contemporary jewelry that is synonymous with post-apartheid South Africa. Despite multiple initiatives aimed at increasing exposure for South African contemporary jewelers, such as events like the Contemporary Jewellery Forum, held at the University of Johannesburg in 2017 and 2018, and the South African Contemporary Jewellery Awards, hosted in 2018 and 2019, the contemporary jewelry movement in South Africa lost its momentum after the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, there are now renewed efforts to revive this movement with the hope that the artists of the Rainbow Nation will leave a lasting mark in the world of contemporary jewelry that shines as brightly as the rainbow that symbolizes our diverse and resilient nation.

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] The primary source of in-depth discussion on contemporary South African jewelry is currently limited to articles written by Professor Fred van Staden. While van Staden has made efforts to document the origins of this practice and shed light on prominent South African jewelry artists from the mid-twentieth century in various articles, there remains a notable absence in the discourse regarding present-day South African contemporary jewelry artists and the intent of their work. One possible explanation for this gap could be the lack of local authors specializing in this discipline and the scarcity of platforms dedicated to promoting South African contemporary jewelry artists and their works.

[2] Fred van Staden, “An Overview of Noted Gold- and Silversmiths in South Africa in the 1950s,” South African Journal of Cultural History 28, no. 1 (2014): 90–113.

[3] Fred van Staden, “Legacies of Immigrant Gold- and Silversmiths during Early and Mid-Twentieth Century South Africa,” South African Journal of Cultural Studies 27, no. 1 (2013): 139–163.

[4] Fred van Staden, “Erich Frey and His Associates: A Unique Contribution to South African Jewellery Design and Its Goldsmith Tradition,” South African Journal of Cultural History 25, no. 1 (2011): 148–179.

[5] Fred van Staden, “Notes on the Hallmarking of Twentieth Century South African Precious Metal Artefacts,” South African Journal of Cultural History 31, no. 1 (2017): 82–105.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] van Staden, “Legacies of Immigrant Gold- and Silversmiths.”

[9] The Mapungubwe Kingdom existed in Southern Africa from around the 11th century to the 13th century. Today, Mapungubwe is considered an important archaeological site and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The kingdom is known for its gold artefacts, most notably a golden rhinoceros which is believed to have held significant symbolic and possibly religious importance. Other gold ornaments, jewelry, and beads were also excavated at the site. This was considered one of the earliest examples of ancient South African craftsmanship. Sian Tiley-Nel, Mapungubwe Remembered (Johannesburg: Chris van Rensburg Publications, 2011).

[10] In the Zulu culture, a cow not only symbolizes material wealth but also cultural identity, social cohesion, and a deep connection to their traditions and spirituality. Patricia Davison, “Visual Narratives of the Anglo-Zulu War: Cattle Horns Engraved by an Unknown African Artist,” Southern African Humanities 28, no. 1 (2016): 85.

[11] Ezio Bassani, “Kongo Nail Fetishes from the Chiloango River Area,” African Arts 10, no. 3 (1977): 36–40.