Also in this series:

- Black Jewelers: A History Revealed—Curtis Tann: Almost Lost to Time

- Black Jewelers: A History Revealed—Bill Smith

- And coming soon: Coreen Simpson

I am beyond excited to introduce the first installment of a brand-new series, Black Jewelers: A History Revealed, that will document the lives of African American artists of the past who have made important contributions to the field of art jewelry. I discovered jewelry through my work on the Susan Grant Lewin Collection, at the Cooper Hewitt Museum. Since then, I have been interested in looking for new ways that we in the jewelry world could expand our knowledge of the figures in the past who have shaped our world today. In this series, we will explore the various stories of different Black artists who were involved in jewelry. Some were full-time jewelry designers, others multidisciplinary artists, and still others came from the art and fashion worlds. They contributed bold new styles, experimentations with materials, and new points of view coming from the African American experience.

It is a pleasure to see the inauguration of Black Jewelers: A History Revealed coincide with Black History Month, a time dedicated to the important deeds of Black Americans and the path forward to securing Black equality and recognition in America. While we take this month to remember all the important African American individuals who contributed their skills and their resilience to the creation of a more perfect union, it is also a moment to reflect on the creativity and inspiration that Black voices have also brought to art and design, including in the field of jewelry. Yet, in addition to being a moment of reflection, it is also important that we start a conversation of not relegating the celebration of Black history to only one month, but to start taking the steps to incorporate this history into the fabric of mainstream American history. Black Americans are not only important to the month of February. They are just as important to every month of US history, as is every other citizen, whether white, Asian, Indigenous, immigrant, queer, non-gender conforming, or any other part of the beautiful complexities that make each and every one of us … American.

I used various methods of research for this series, and hope it will bring life to the great deeds that each of these artists contributed to the world of art jewelry with varying degrees of success.

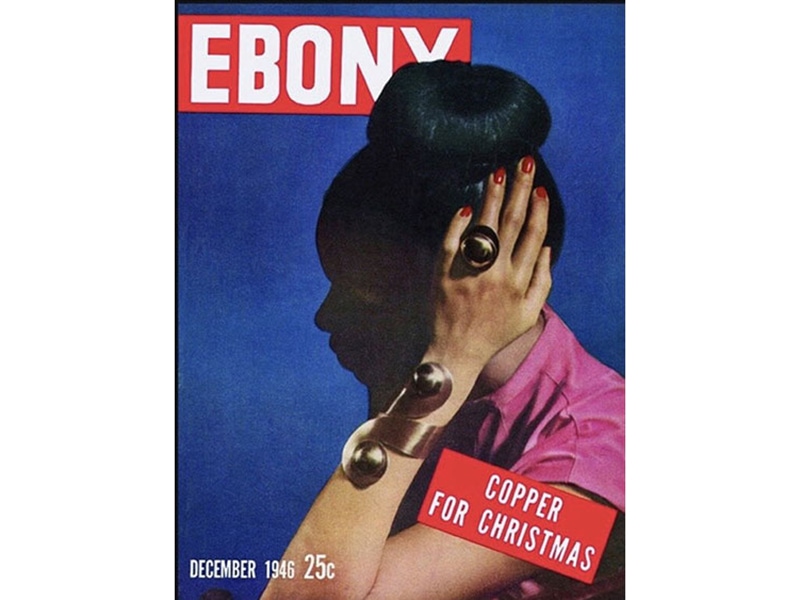

This series will examine the artistic works in copper of Winifred Mason, who worked during the Harlem Renaissance to design pieces for jazz greats such as Billie Holiday. We will also view works by artists who used more unorthodox materials, like C. Edgar Patience, who designed works using black coal and had famous clients as renowned as President Lyndon B. Johnson. Some prominent jewelry designers worked in fashion. Bill Smith’s designs graced the covers of Vogue magazine and Harper’s Bazaar in the 60s and 70s, modeled by celebrities such as Twiggy and Cher. Patrick Kelly, known for his bold and flashy fashion of the 80s, also had a connection to jewelry in the bold pins that were iconic to his brand. He sold them commercially along with his arresting designs.

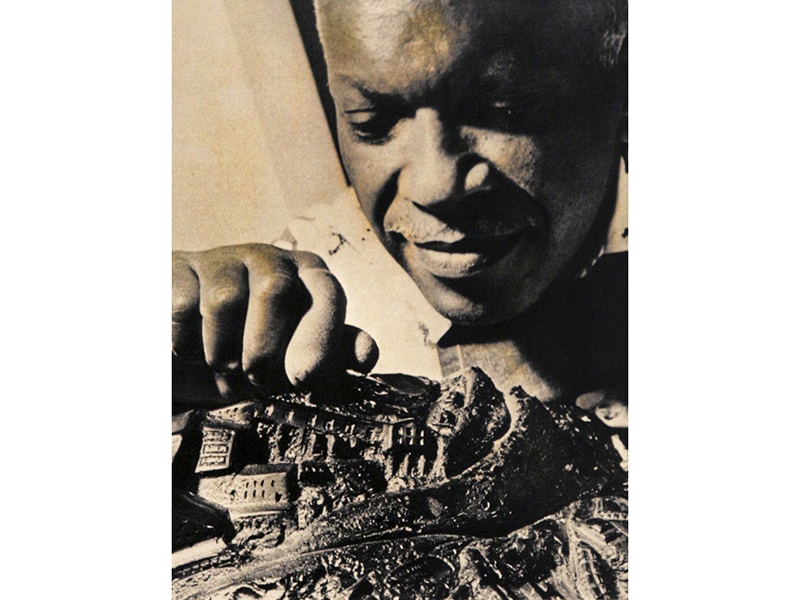

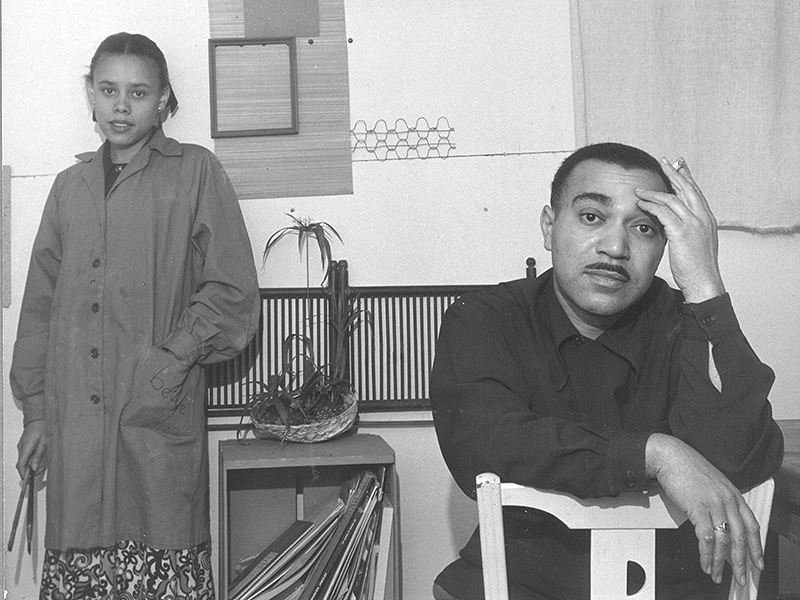

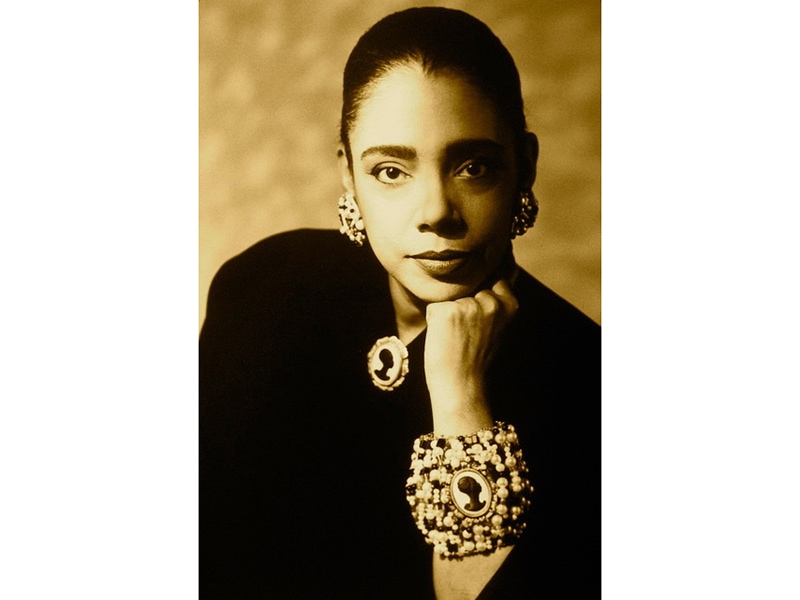

We will look at artists both known and unknown in the art world, from the infamous Betye Saar to her lesser known but equally important friend the enamel artist Curtis Tann. We’ll explore the commercially successful works of Coreen Simpson and the culturally creative ones of Vaughn Stubbs. Each of these artists, prominent or less so, made their own important contributions to the world of contemporary art jewelry, and now is the time to acknowledge their brave and courageous efforts.

How does one recover a past that has been nearly forgotten? How does one bring back memories of the lives and successes of major figures in the jewelry world that have been lost in the yellowing pages of old directories and fashion magazines? How does one, especially, accomplish this task for a group of people who have historically been left out of the main narrative when it comes to discussing metalsmiths of the 20th century? These were the first questions that came to mind a year ago when I began this project. As the anger and pain of the killing of George Floyd changed the world in a summer of marches and solidarity against racial injustice, questions started to arise throughout America asking how Black lives have been represented, especially in a country that has yet to confront its harrowing history of racial injustice and inequality.

It was during this period of social reckoning that I began my research in collaboration with The Jewelry Library, in New York. I sought to excavate how much the Black community contributed to the world of jewelry design and in what ways their work was—or wasn’t—recognized in the larger fabric of American society. Yet the more I searched for sources and information about many of these extraordinary designers, the more the challenges and complications of the task became clear. At the moment there are no major texts that specifically explore the history of Black art jewelry. Many of the books that discussed Black craft in the past went out of print years ago. Very few major publications or journals profiled Black artists or jewelers in the past, and many stories of their successes were relegated to Black-owned magazines, which were few and far in between. In addition, many pieces or works by artists, or any photographic evidence of their existence, have been lost. They disappeared through reuse of precious materials, lack of proper documentation, plain negligence, or denial of their merit.

Yet despite the difficulty of recovering this history, I discovered a wondrous world that existed under the surface, one filled with legendary stories of camaraderie and creative excellence during times of struggle and of social change. I uncovered mentions of metalsmiths and craftspeople of the late 19th century who had just broken out of their chains of slavery to break into a different world, one in which they established their identity through craft. I found stories of jewelry designers who rubbed elbows with some of the greats of the Harlem Renaissance and contributed their skills to a flourishing period of African American artistic exploration. I also read tales of artists exploring new avenues of success with feelings of liberation after the civil rights movement. And I glimpsed the future of Black jewelry by exploring the contemporary conversations of today. Each of these discoveries only confirmed to me that not only were there important Black artists in the world of art jewelry, but also that so many of these artists had important stories that, either consciously or unconsciously, society has left to be forgotten and ignored.

I compiled the research on each of these individuals by perusing newspapers and magazines that profiled these artists or recorded important events in their lives or careers. Other artists had examples of their work documented in leading fashion magazines and advertisements at the height of their fame. In addition, I located some stories in university archives via oral histories collected from living artists. I also personally interviewed some artists, seeking more information about their lives, their work, and the reasons for their dedication to the world of art jewelry.

By bringing these tales to the readers of Art Jewelry Forum, this series aims to act as a catalyst to correct the misdeeds of history done to these individuals who, through their hard work and dedication, worked to make names for themselves across the field of metalsmithing. With this research, I want to reveal the lives of amazing artists and designers to a more general public and start a process of communication that will uncover more stories and research on these people who have been ignored for so long. I hope to secure their legacies and importance as great figures in the world of art jewelry who will continue to be studied and discussed for generations to come.