For the revolutionary fashionistas of the 60s and 70s, Bill Smith was there to dress them in jewelry. He was a designer regarded as a sensation, awarded for jewelry styles that captured the freedom and exuberance of the era. The covers of fashion magazines showed his long strings of pearls and large spring collars around the necks of models both famous and unknown. Yet for a designer who gained great love and adoration from the fashion world, his story suddenly disappeared, and his legacy became a forgotten page of the great textbook of history. How did he rise to such a point of acclaim, and how did he disappear so quickly?

William Franklin Smith was born in 1933[i] to the family of Robert Smith and Elizabeth Foree in Madison, IN, US.[ii] His father worked as a carpenter, and served as a soldier in WWII, while his mother was a homemaker. Smith also had a sister, Gladys, with whom he had a very close relationship throughout his life. During his childhood, he was encouraged by his family to pursue the arts. As an adult he had fond memories of learning from his public school art teacher Vivian Gray. In addition to visual art, he also began pursuing a major interest in dance, which would be his first major focus. His interests in the arts continued after high school, and he attended Indiana University to study dance, performing for the Jordan River Revue and a production of Kiss Me Kate, among other musicals. While he was honing his footwork, he also engaged in other hands-on activities, and he began studying metalsmithing at the school under the tutelage of the famed American silversmith Alma Eikerman. After graduating with a degree in metalsmithing, Smith moved to New York in 1954, where he attempted to formally pursue a career in dance. He was invited by famed dancers Martha Graham, Jose Limón, and Doris Humphreys to study under them, and he quickly seized the opportunity, eventually joining as a member of the Alwin Nikolais Dance Company.[iii] While continuing to dance, he held other jobs, including work as a messenger in the Garment District and as a librarian at Columbia, until he was called on to use his metalsmithing skills for another side job.[iv] For this gig, Smith began working in a Greenwich Village jewelry shop. He ended up taking over after the owner had an accident, and he made jewelry while he tried to find success in dance. As his work in jewelry gradually took center stage over his efforts in dance, he eventually decided to focus on jewelry full time in 1958.

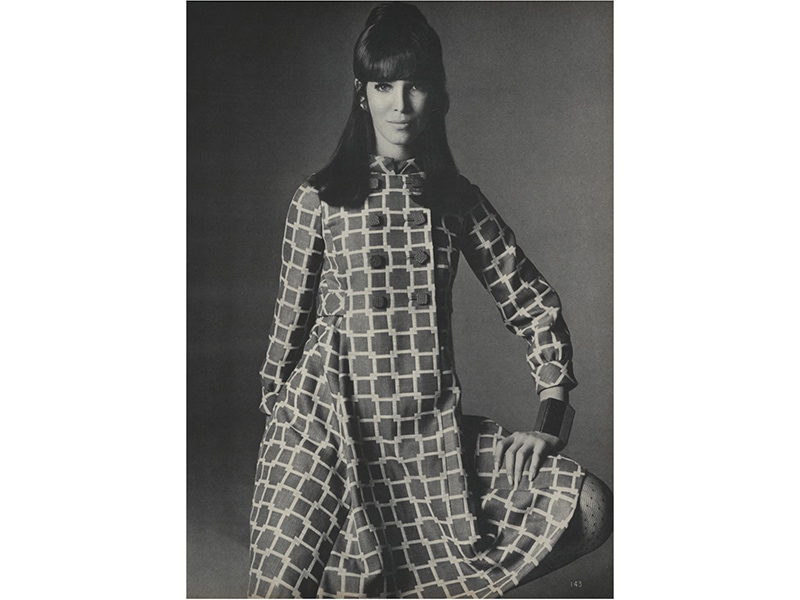

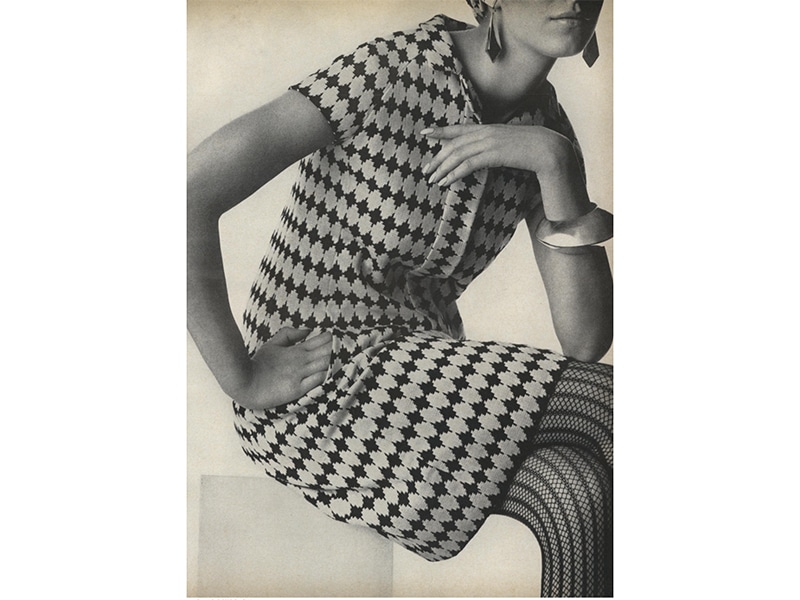

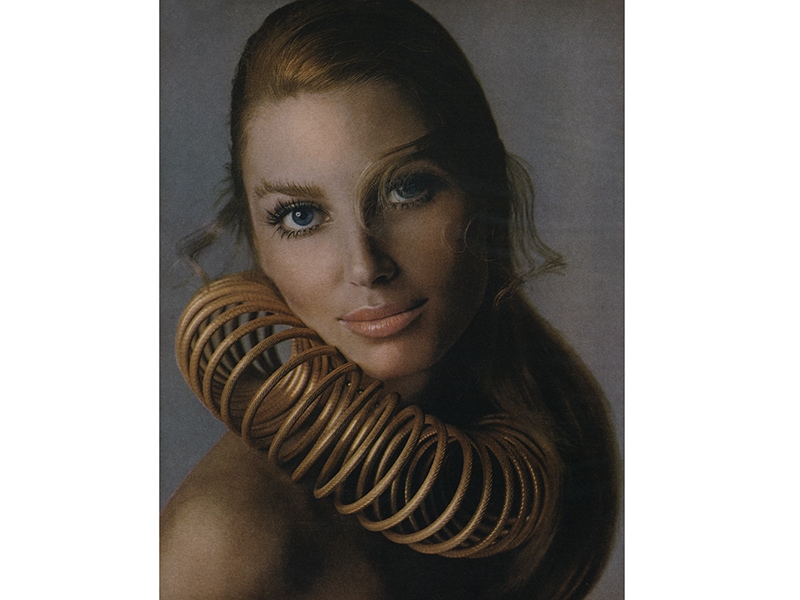

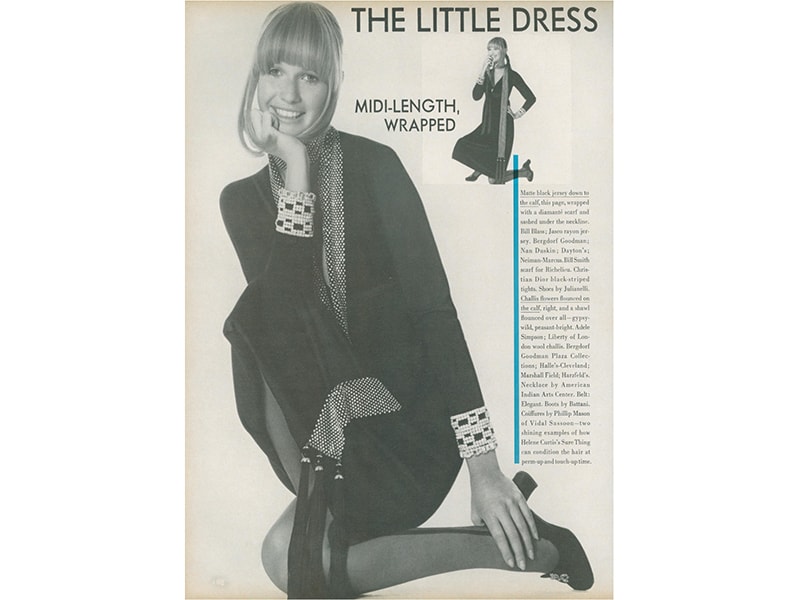

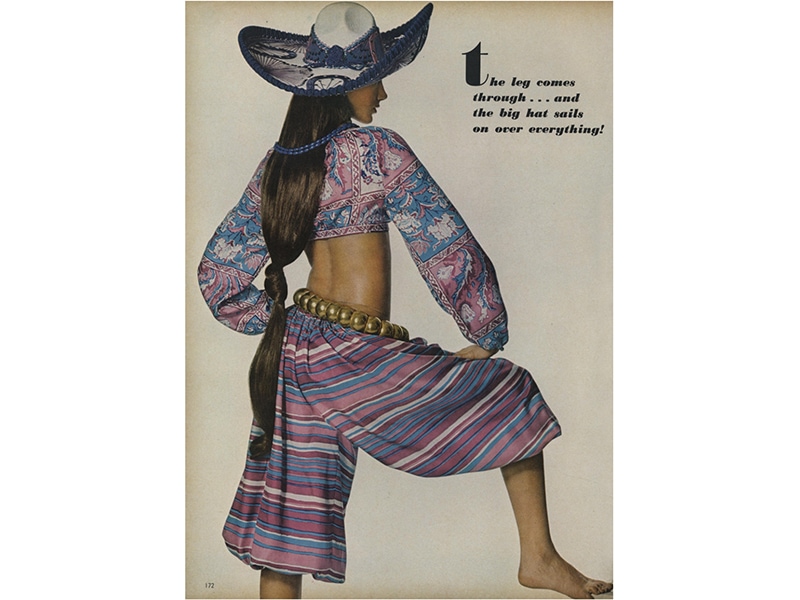

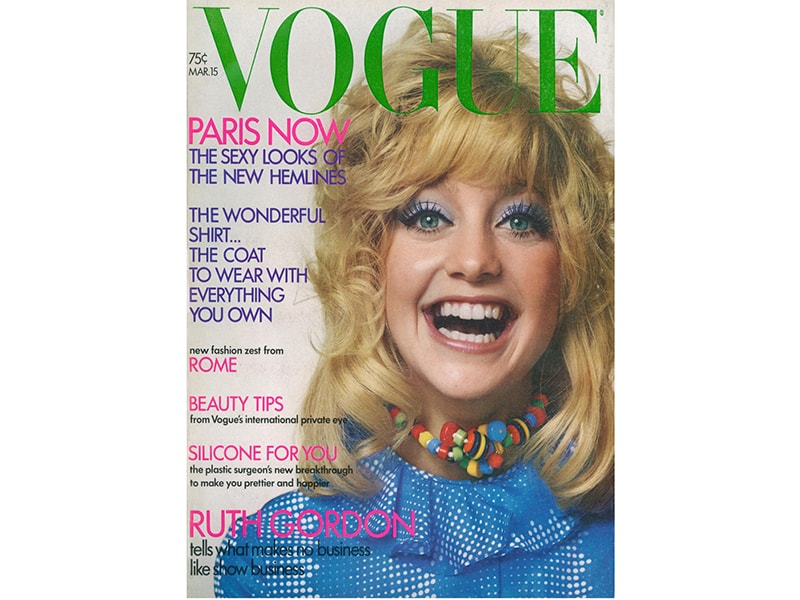

His first stint with mainstream achievement started in his first company, Smith St. Jacques, which was located at 164 East 33rd St. He founded the company around 1960 with his business partner and upcoming actor Raymond St. Jacques, who would eventually become famous for playing the role of Simon Blake on the 60s Western show Rawhide. Although working as a partnership, Smith would often tease in interviews that he did most of the work in the company.[v] Looking to incorporate the bold and modern styles of the early 60s in their work, Smith St. Jacques created bangles, necklaces, earrings, and other items from brass, leather, and tassels that emphasized size and experimentation in costume jewelry. Fame and success came quickly, as celebrities such as Lena Horne and Loretta Young bought pieces, while department stores such as Lord & Taylor and Henri Bendel featured Smith St. Jacques on their counters. Their extravagant works also garnered editorial coverage, as their works accessorized models in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, featuring famed singers and models like Cher and Twiggy.

In addition to his early feats in jewelry in the public sphere, Smith also gained the interest of the museological world, as his work joined the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, in New York (now called Museum of Arts and Design), and was shown in exhibitions. [vi] Yet the success found in Smith St. Jacques was only the beginning of the broader accomplishments Smith would find in creating costume jewelry in the late 60s.

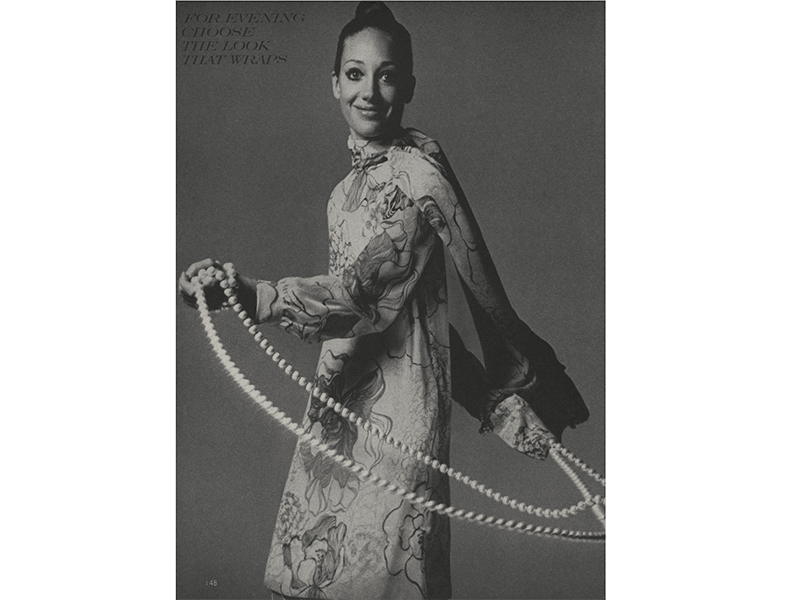

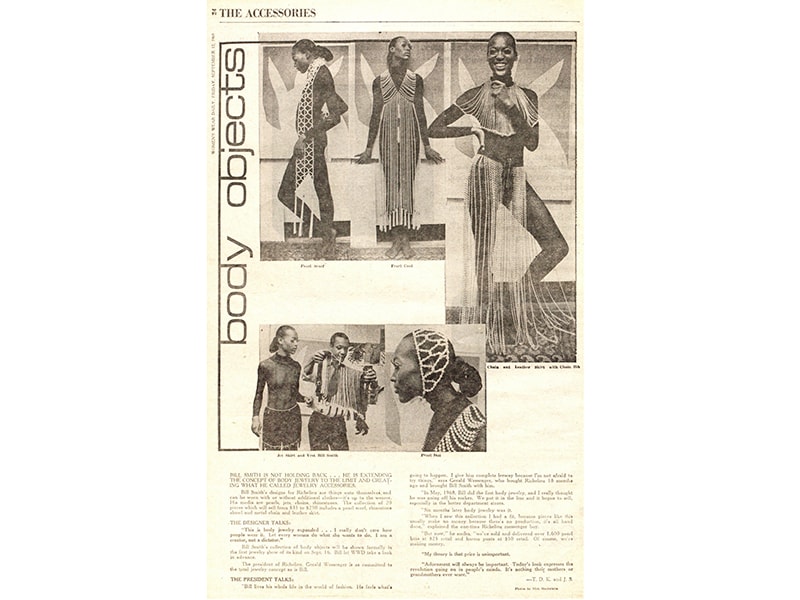

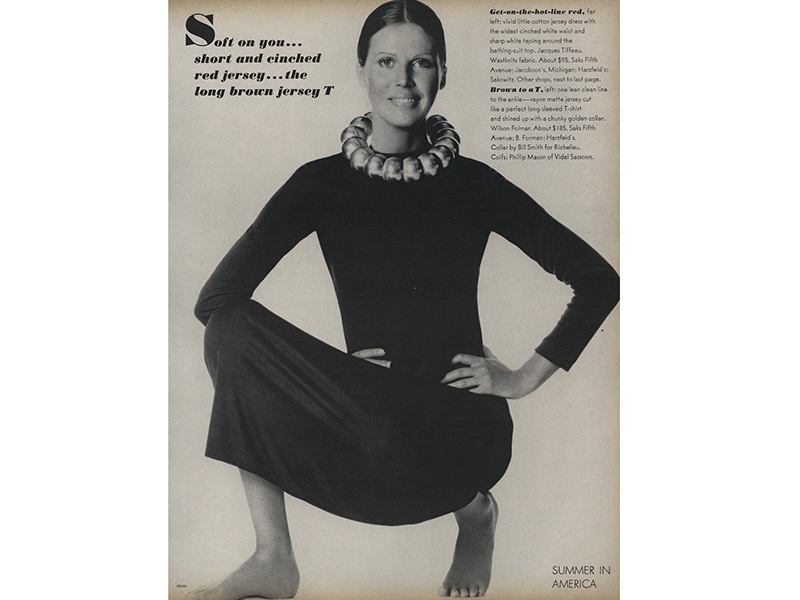

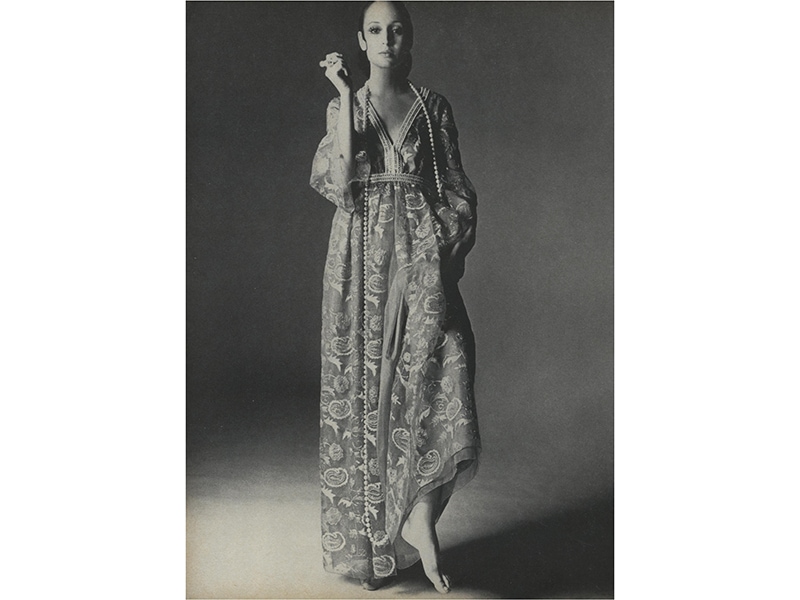

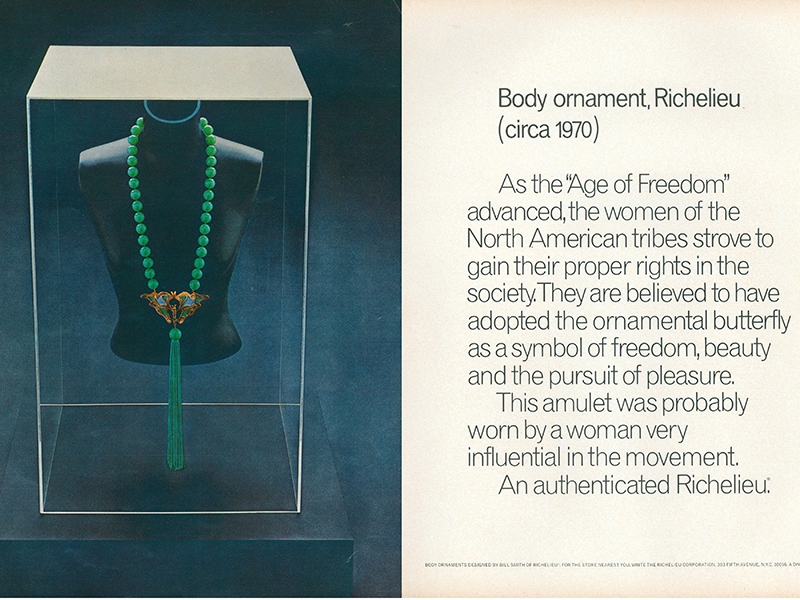

In 1968, Smith closed his company to begin creating jewelry for Richelieu, which at the time was one of the biggest costume jewelry companies in the United States. He originally worked for the company as a freelance consultant, but caught the attention of its president, Jerry Wessenger. The company was originally known for its classic strings of fake pearls, but Wessenger hired him to “put fresh breath” into the business, without realizing the artistic potential and flair Smith would bring to their boardroom.[vii] On the day when Smith walked into the Richelieu’s 5th Avenue location, he shocked company leaders by introducing new forms of their jewelry, redesigned with a wild extravagance. Upon encountering a pantsuit made of strings of Turkish coins, a matching pair of bralette and trousers made only of pearls, and many other unorthodox designs, the officials were filled with consternation and fear.[viii] They could not have predicted the radical emergence of body jewelry in the costume world. These designs would signify one of the most iconic moments of Smith’s career.

“You can use anything you want to,” Smith said in an interview for The Kokomo Tribune, “but don’t make it look like what it is—give it another dimension.”[ix] Smith had a deep willingness to take risks and experiment with jewelry, designing fake pearls into full fashion garments with hints of erotic flair, creating bold collars and belts made of brass baubles, and incorporating unorthodox materials, such as plastic and leather, to give the illusion of high end jewelry at an affordable cost.

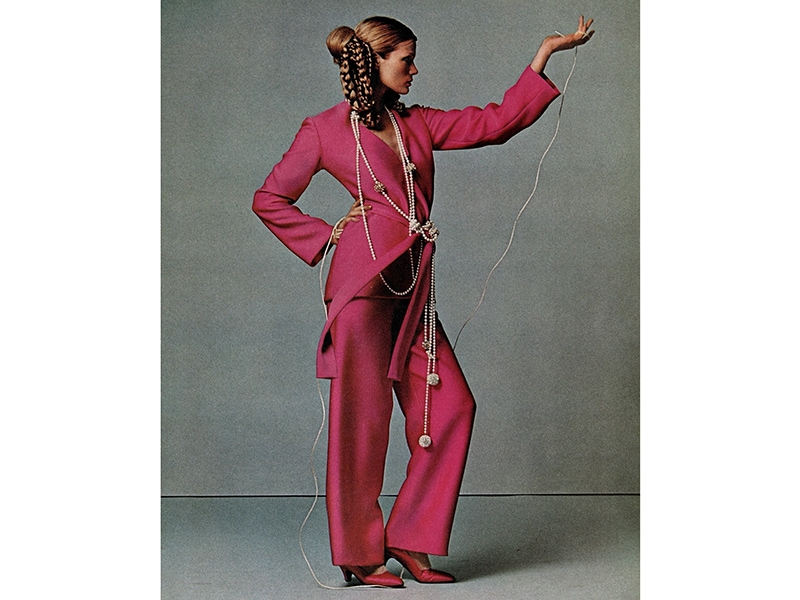

In addition to predicting the jewelry of the future, he also used past influences to rethink questions of body decoration in the Western world. He would often draw upon influences from African, Persian, and Seminole styles to explore costume jewelry away from the Western lens, inviting global heritage into an often excluded space to be appreciated.[x] He also gained many of his ideas by exploring design history in museums, noting in one article how he often went to the Cooper Hewitt museum in New York for inspiration.[xi] In addition to looking toward non-Western traditions, Smith continued to design different styles of Richelieu’s famous signature pieces of fake pearls, expanding the definition of how pearls are supposed to be worn on the body. He transformed them into full body pieces, designing them as scarves, coats, skirts, vests, and even head pieces. “Pearls won’t ever go out [of style],” Smith said in The Kokomo Tribune, “They’re an old tradition like apple pie.”[xii]

In his decision to drape his customers in long chains of pearls, Smith considered freedom of self-expression to be an important part of wearing his jewelry. “I really don’t care how people wear it,” Smith said in an interview with Women’s Wear Daily. “Let every woman do what she wants to do. I am a creator, not a dictator.”[xiii] Smith gave his wearers the freedom to express their own identities and personalities, encouraging the customer to define their jewelry, rather than have the jewelry define them. This freedom in jewelry style coincided with the movements of liberation that characterized the late 60s and early 70s. Body jewelry eschewed the rigid constraints of social expectation, and prepared for the era of fun, dance, and decadence that came to portray the upcoming decade.

The body jewelry in Richelieu’s collection became a massive hit for the company, and it brought Smith renown and an even wider audience. After working just two months for the company, he was promoted to vice president and became its head designer. For the next few years, he handled most of the major design campaigns of the company. His jewelry was featured in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Women’s Wear Daily, and many other fashion magazines, and Smith even made a TV appearance on the Today show, displaying his body jewelry with Barbara Walters. His work also continued to spark museum interest, and half a dozen of his pieces entered the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1969.[xiv] His designs for Richelieu received awards; in 1969 he won the Swarovski Award for Designer of the Year. Then in 1970, he won the coveted COTY award in fashion, becoming its first black recipient.[xv] Conflicting reports also note that he may have received his first COTY in 1965, however, more research is needed to confirm this information.

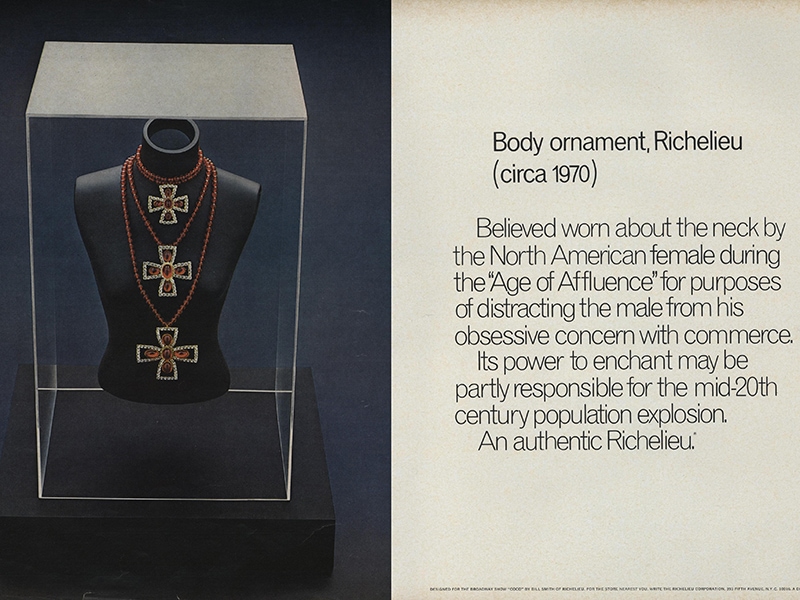

While becoming a darling of the fashion world, during the height of his fame his experimental costume designs also attracted the attention of Broadway, as he became the jewelry designer for the 1969 production Coco.[xvi] A show which visualized the life and influence of French designer Coco Chanel, the production starred the legendary Katherine Hepburn in the title role, and featured set and costume designs by Cecil Beaton, with music by André Previn. To accessorize the real Chanel designs, Smith designed gold chains with ruby red German crosses and added pearl designs, which captured the spirit of the Roaring 20s. The show was nominated for multiple Tony awards, winning one for Best Actor in a Musical. Despite its beginnings as a Broadway sensation, the show failed to keep the same critical acclaim after Hepburn left the role eight months later, and it closed on Broadway, heading on a national tour in 1971.

Smith’s initial employment at Richelieu, and later partnership there did not last for long. Early in his career he received no credit in the labeling of his designs, but later his designs were exclusively marked as “Bill Smith for Richelieu,” yet this change in credit was not enough of an incentive for him to stay. He left in 1972 to set up his own company, Bill Smith Design Studios, Inc, with the help of Kenton Corp, after being introduced to them by Naomi Sims, one of the first African American supermodels.[xvii] The formation of this new company gave Smith more freedom to work with other designers and facilitated a chance for him to break out of costume jewelry. He began collaborating with Cartier (see an example of a design here), fur company Ben Kahn, and leather goods company Mark Cross, producing products of precious metals and leather.[xviii] During this time he participated in a photo shoot with Sims, for Look magazine, adorning her in a custom-made Cartier collaboration: a gold hat and cuffs printed with African designs.[xix] Sims friendship to Smith helped him to move toward a more independent career, and hopefully towards greater achievements.

Unfortunately, this move toward his own autonomy seemed to also signal the end of his moment in the limelight of the fashion world, as fewer and fewer articles exist to document his later work in the 70s and 80s. During this time, he continued to produce and collaborate with other companies, providing designs for Laguna, Omega Inc., and Hattie Carnegie manufacturing, yet without the same levels of prominence he had had with his earlier work. Bill Smith Design Studios, Inc., was discontinued in 1981, although he had plans to restart the company in the future. He seemed to reflect on the unforgiving nature of the fashion industry in an interview at the time, stating, “I’m cynical because of the waste of talent I see. Talent sustains you once you’ve made it, but to become successful you have to be manipulative.”[xx] This cause for cynicism still seems just as apparent today, especially in regard to important black members of the fashion world such as André Leon Talley, an acquaintance of Bill Smith, who, despite his clear influence on fashion criticism, ended up alone and nearly evicted from his home by the time of his death in 2022.This treatment is most apparent in fashion’s tendency to forget the important people who help move it forward, especially forgetting the African American community, which has often been discredited for its past achievements and relegated to a footnote in the historical texts of time. Smith became increasingly forgotten as the push for black representation in society lost its importance to other issues in America.

The saddest aspect of the nature of time and fame is most visible in Smith’s death, in 1989, due to complications of AIDS-related pneumonia. According to his grandniece, at the time of his death, Smith had been disowned by his father because the man couldn’t tolerate Smith being gay, and he only kept in contact with his sister, who always supported him no matter what. [xxi] As he was dying, his sister was the only family member who visited him, and she cared for him until his final days. Unfortunately, possibly due to stigma around AIDS at the time, no records can be found, including obituaries or contemporary articles from the late 80s. Yet even current research written about Smith fails to note when or how he died. It seems as if Smith’s contributions to jewelry and fashion became so unimportant that researchers haven’t taken the steps to determine his recent whereabouts, leaving Smith in a liminal state of life and death, his existence obliterated through lack of care.

Bill Smith’s story is an essential example of the important contributions that African American designers brought to the world of jewelry, and the necessity of preserving these meaningful stories for the future. Smith combined brass, leather, fake pearls with experimentation and freedom of expression to create body jewelry that captured the world of fashion in the 60s and 70s and created a sensation. Dressing celebrities and models in bold jewelry, Smith’s accomplishments, which ranged from awards and accolades from Vogue to accession in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, predicted a future of recognition for Black talent. Yet his story is also one of caution, warning us of the fleeting power of historical relevance, and the fact that culture can nearly eradicate the crucial contributions of the past that have led to the rights and privileges we enjoy in the present. It is now our responsibility to keep these stories alive, so these designers will not be forgotten.

[i] Conflicting reports also state that he was born in 1936.

[ii] Jane Allison, “Dancer Finds Career. In Fingers, Not Feet,” Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, IN), Nov. 15, 1959, 17.

[iii] Joan Gilmore, “Bill Smith To Lecture,” Daily Oklahoman (Oklahoma City, OK), Feb. 27, 1972, 76.

[iv] Allison.

[v] Lana Ellis, “Bill Smith Makes a Name in Jewelry,” The Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), Nov. 23, 1969, 131.

[vi] Angela Taylor, “Costume Jewelry Goes Big, Flashy, and Phony,” New York Times (New York, NY), Aug. 16 1965, 20.

[vii] Ellis, 131.

[viii] Marian Christy, “Just Plain Bill Smith Creates Dazzling Jewelry,” Boston Globe (Boston, MA), Sep. 12, 1969, 34.

[ix] Joy Stilley, “Designer Says Jewelry Conveys ‘Individuality,’” Kokomo Tribune (Kokomo, IN), Mar. 10, 1969, 8.

[x] “The Jewelry: Smith’s Standouts,” Women’s Wear Daily (New York, NY), June 12, 1970, 24.

[xi] “Jewelry Genius Becomes a Veep,” Ebony (Chicago, IL), Oct. 1968, 92-97.

[xii] Stilley.

[xiii] Trucia Kushner, “The Accessories: Body Objects,” Women’s Wear Daily (New York, NY), Sep. 12, 1969, 24.

[xiv] Eugenia Sheppard, “Making Jewelry like Eating Steak,” Hartford Courant (Hartford, CT), July 17, 1969, 26.

[xv] “Bill Smith Recipient of Coty Fashion Critics’ award,” Baltimore Afro-American (Baltimore, MD), Oct. 3, 1970, 13.

[xvi] Opal Crockett, “Hoosier Bejewels Broadway’s ‘Coco,’” Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, IN), Feb. 9, 1970, 6.

[xvii] Gemexi Team, “Bill Smith—First Black Jewelry Designer to Win Prestigious Awards,” Gemexi, last modified Sep. 16, 2015, web.

[xviii] “Bill Smith—The Maverick,” Black Enterprise (New York, NY), July, 1981, 36.

[xix] “Fashion Now: Black Pow!,” Look (Des Moines, IA), produced by Jo Ahern Segal, April, 1972, 52–53.

[xx] “Bill Smith—The Maverick.”

[xxi] Briton Sargent (Bill Smith’s grandniece) in discussion with the author, July 14, 2022.