Also in this series:

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Demetri Broxton’s Beaded Boxing Gloves

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Hollis Chitto

- Jewelry||Adjacent: Monica Canilao

This is the second article in a series focused on artists whose work is adjacent to jewelry. For my purposes, jewelry-adjacent artists use material, techniques, or themes related to jewelry practices. The body is present in their work, not necessarily as the recipient of adornment, but in the importance of the physical body to their form, topic, or narrative. The adjacency of these artists to jewelry provides fresh perspectives to those of us immersed in the field. A companion to this article published in Metalsmith magazine (volume 41, number 3) as part of their ongoing Jewelry Thinking series.

The global pandemic has brought mortality to the minds of everyone. The loss of life is incalculable, making grieving familiar, even as the pandemic disallows for the physical connection of traditional mourning practices—even sitting by someone’s bedside as they pass away. In her essay, “Grief, Interrupted,” for the London Review of Books, Jude Wanga speaks of the disconnectedness of grieving right now:

There is no closure. No final chapter. No poignant moments of holding hands with my loved ones and letting them know I loved them as they take their final breaths. No family sitting with me for a week, to bring food, care, love, hugs. No hugs at church, or at the cemetery. There’s just nothing. There may never be anything again. I am broken. I am a skipping record, a stutter in time. This is grief, interrupted.[1]

But grieving isn’t new, though it is more often experienced in discrete moments and not at this global scale.[2] Angela Hennessy[3] uses her practice to process her relationship to grief personally and culturally as a Black, queer woman. In doing so, she creates a place for collective mourning and a space to honor those who came before, where the viewer is invited to consider what grieving means.

Victorian mourning jewelry was an early influence during her graduate studies at California College of Art, rooted in her high school and undergraduate studies in jewelry. Victorian mourning jewelry provided a way to keep a deceased loved one physically present and connected to the living, using their hair to create intimate objects of remembrance. Queen Victoria began the trend after the death of her husband, Prince Albert, in 1861, wearing a locket of his hair for the remainder of her life.[4] Victorian mourning traditions also included lengths of hair braided into bracelets, strands of hair intricately arranged in pendants, and visually complex wreaths adorned with the deceased’s hair as flowers and flourishes surrounding their portrait.

As Hennessy researched this tradition, she realized that hair had a place in grieving rituals across culture and history. A quick Google search on hair and mourning results in a wide range of bereavement practices. The recently bereaved might shave their heads (Nigeria), not shave their facial hair (Greece), not comb or groom their hair (Philippines), keep a lock of hair for a year (Lakota), or use their hair to cover their face (Ancient Egypt). What fascinated Hennessy in this variety is “how hair became the material that connected one to the dead, while marking the separation caused by death.”[5]

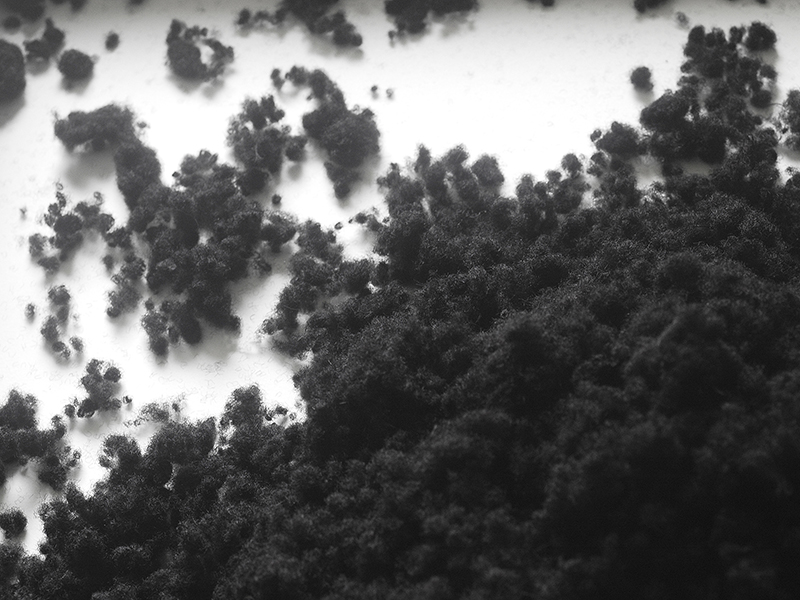

Hennessy’s exploration of hair began with fuzz. As she deconstructed black velvet, separating the velvety fuzz from the threads of the backing, she recognized its resemblance to a Black barbershop floor after a haircut. Her first piece using the fuzz, Blacklets: A Speck of Soot or Dirt, paid homage to this material discovery and questioned its identity. Later, she applied the velvet fuzz to woven Velcro in a large, gold, oval frame, creating visual texture and contrast. The shape of Mourning Weave references a traditional locket, one that might have held a snippet of hair, and the oval frame of Victorian portraiture, often placed in the center of Victorian mourning wreaths.

It’s interesting to note that while Hennessy’s starting point was clearly jewelry informed, it didn’t result in creating jewelry. Art-making often leads artists down unexpected pathways. Melanie Bilenker is a white American artist whose work is also rooted in Victorian mourning jewelry.[6] Her work remains connected to the historic techniques of Victorian hair jewelry, expertly reimagined with modern materials. She uses her own hair to create intricately drawn domestic scenes showcased in lockets, poignantly intimate and powerful in their simplicity. That Bilenker and Hennessy produced such disparate work from the same historic reference highlights the wealth of interpretations that come from including different voices in art world conversations.

One reason for the diverging exploration is that the hair Hennessy uses is her own, biracial and not straight, which carries added cultural meaning. White hair has the privilege to simply be a line. The hair in Hennessy’s work is not neutral. It is Black hair, Black women’s hair, Black queer hair, biracial hair. By using Black hair as material, she references a complex cultural history that includes ancestral trauma and cultural oppression as well as the pride, beauty, and joy of Blackness.

Hennessy’s personal experience provides a narrative that threads through her work. The absence and discovery of family connections, the struggle of defining oneself when embodying multiple identities, the finality of a parent’s death, a near-death experience, the weight of ancestral grief coupled with the continuation of violence against Black bodies today, the requisite grieving of being Black in America. Through her creative research, she holds space to experience the beauty and anger, joy and sorrow, that can exist simultaneously.

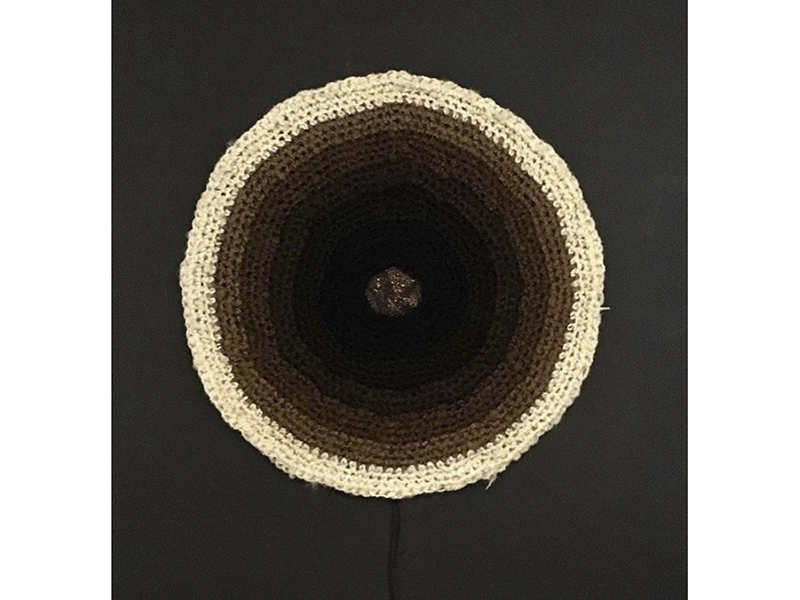

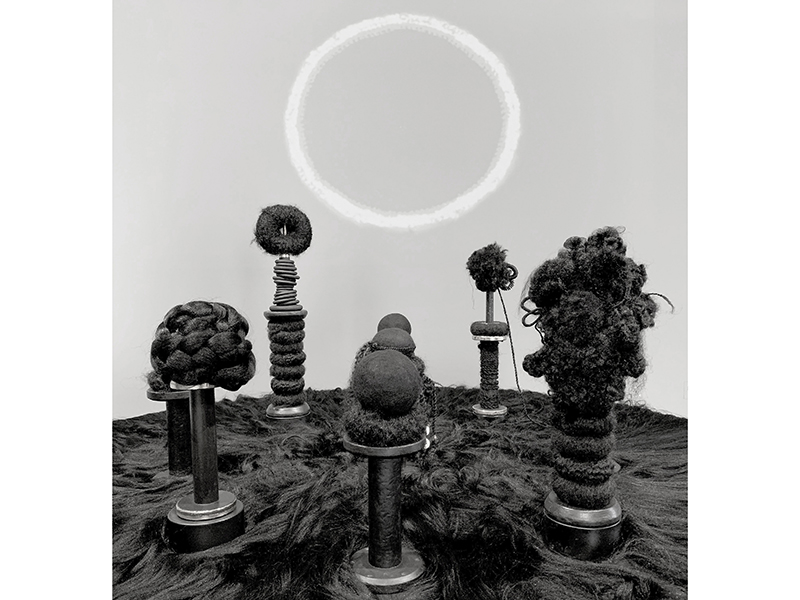

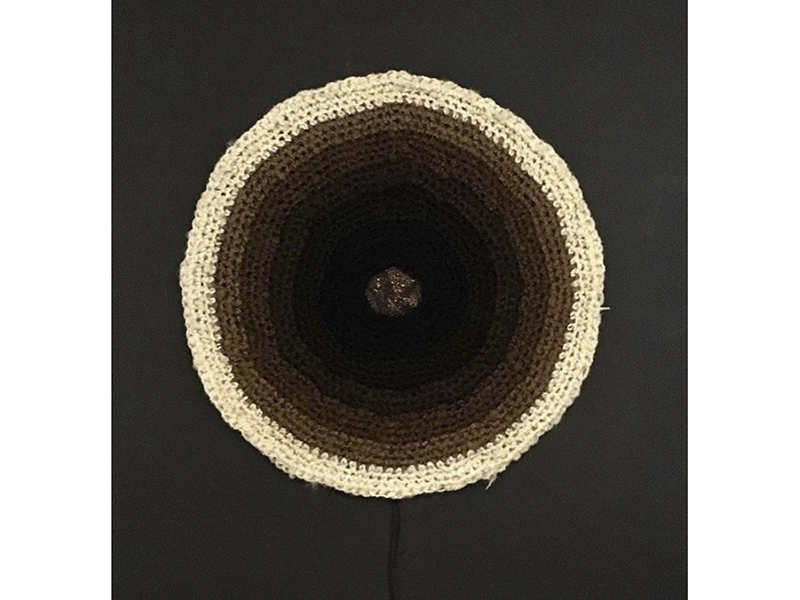

Several of her pieces are made of crocheted synthetic hair in shades that reflect the diversity of her family, combined with her own hair. Black Rainbow and Setting of a Black Sun are large sculptural crocheted pieces made through the repetition of small interlocking loops of hair. Their macrame quality reflects nostalgia for Hennessy’s childhood, one growing up in small towns on the Northern California coast in the 70s. She refers to the crocheting process as a way to hold things together, a meditative act of physically connecting her different racial histories, the disruption of her family unit, and the layers of grief connected to existing in this world that considers your presence “othered.”

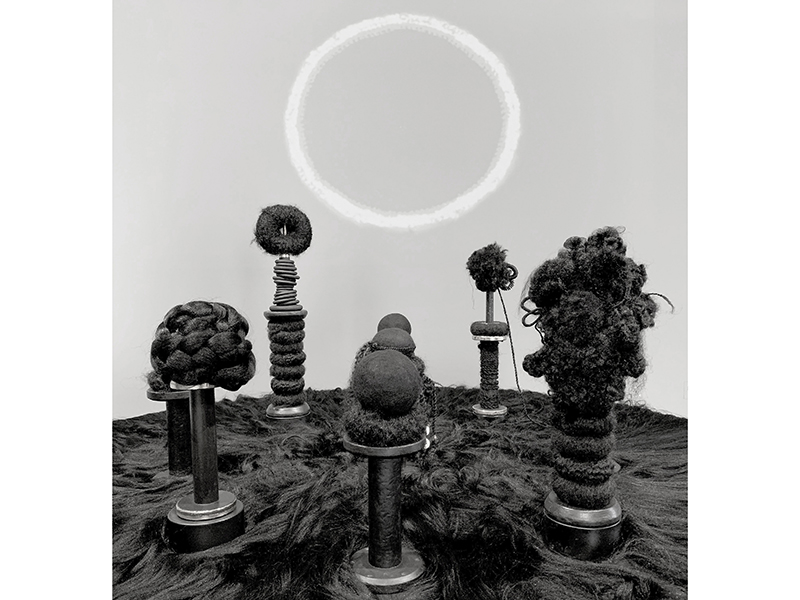

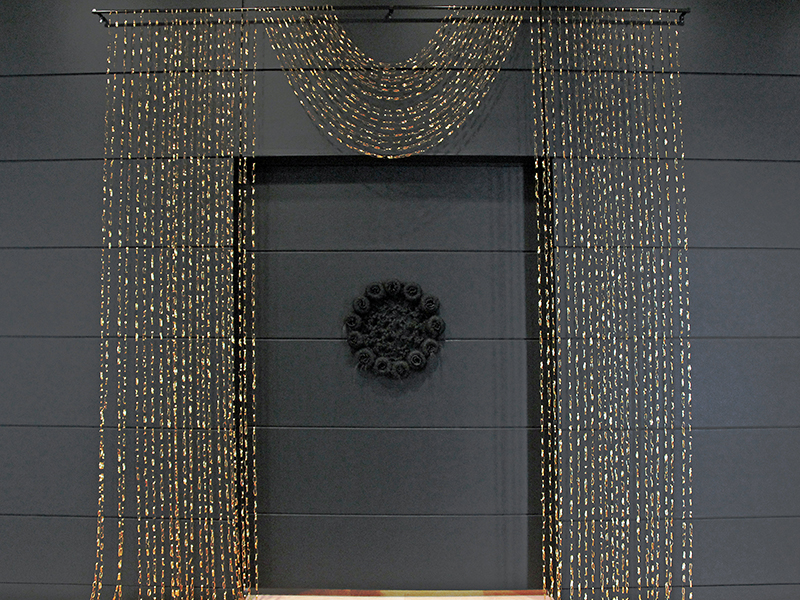

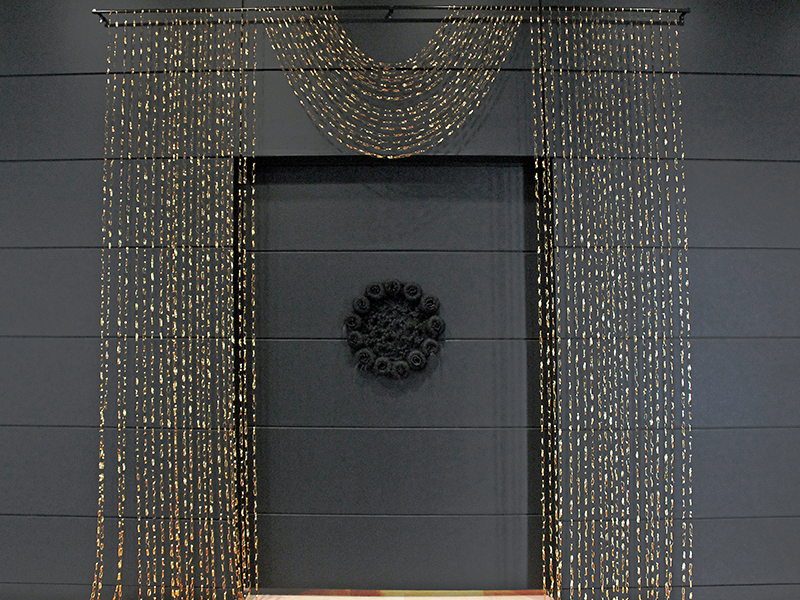

Much of Hennessy’s practice recognizes the vagueness of grieving, the longing for things unknown and difficult to name. Unidentified Grieving Objects extend from the ceiling as ropes of Black or blond synthetic hair interrupted by voluminous poufs in the 2017 exhibition When and Where I Enter, at San Francisco’s Southern Exposure (SoEx) gallery. The monumental Mourning Wreath moves the Victorian wreath tradition off the wall, supported by a single steel column that invites approach from all sides, leaving nothing hidden from view. It is laden with swags of synthetic black hair braided, woven, and meticulously arranged. Gold-leafed copper medallions suspended from chains drape into the center of the wreath from the top.

The visual effect of these pieces in relationship to each other is striking, the tones of gold with shades of blond to brown to black hair set off against the black walls of the gallery space. Painting the white walls, suggested by the SoEx curator and embraced by Hennessy, was a subversive and effective way to disrupt the white cube. Hennessy had previously shown her individual pieces on black walls, set apart but included in white-walled venues. Hennessy’s work requires an unapologetic reimagining of the whiteness of the art world. By painting the gallery from floor to ceiling, she signals a shift in expectations to a viewer familiar with the typical gallery experience and challenges the whitewashing within art spaces.

Hennessy’s handling of hair as a material is seductive. She treats hair as a textile with luxurious texture and visceral tactility, perfectly coiffed and arranged in monumental forms, beautifully lit and set apart. The etiquette of art denies viewers the fulfillment and satisfaction of touching the sculptures, denying, too, the privileged desire to touch Black hair and in so doing to insert power, ownership, and dominance over Black bodies. Tiff Massey’s neon piece Bitch, Don’t Touch My Hair, was made as a self-portrait but, as she says, speaks for every person of color who has curly hair,[7] unequivocally stating the disrespect inherent in this invasion of someone’s personal space. The tension between the wish to break the oft-forgotten taboo of touching Black tresses and the refusal of the wish due to the etiquette in what have been traditionally white spaces is rather poetic.

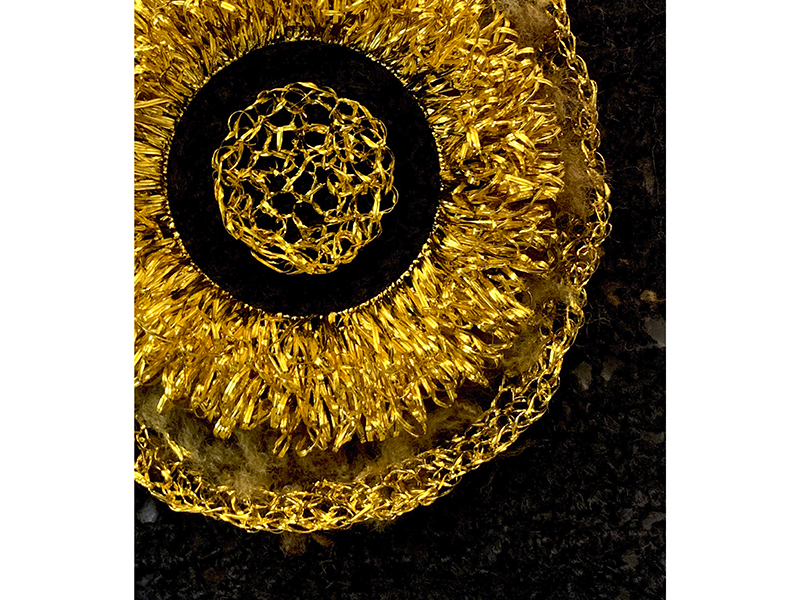

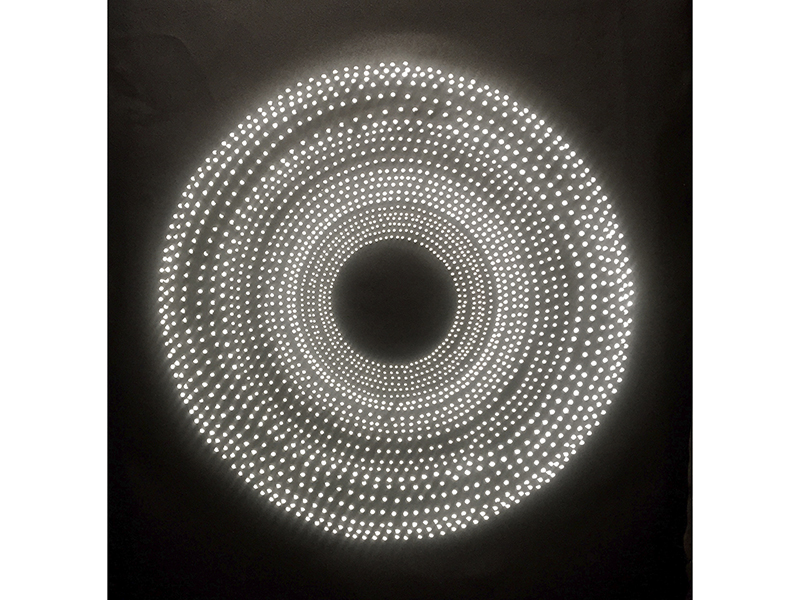

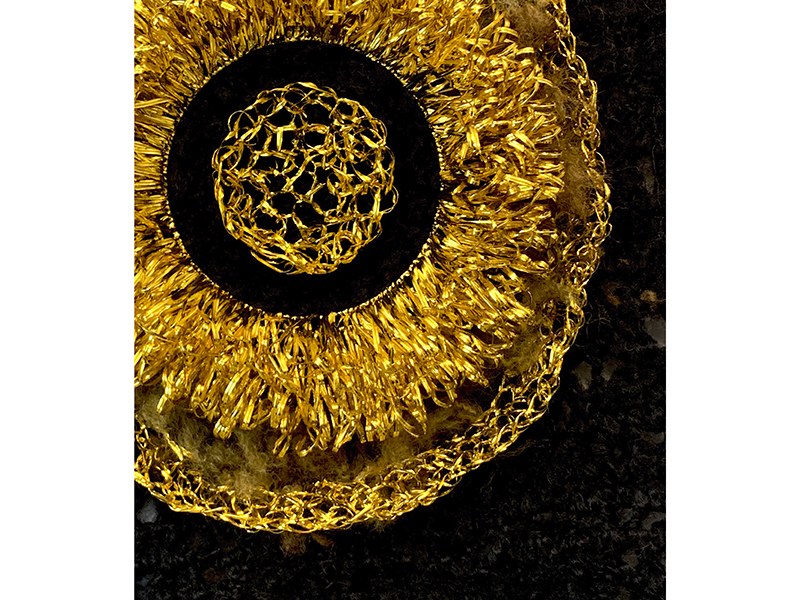

While hair is the primary material Hennessy works with, it isn’t the only one. She distributes gold, both real gold leaf and materials that mimic gold, in varying quantities throughout her pieces, referring to her interest in jewelry. The inclusion of this material brings reflections on concepts of value, as well as the visual language of light and light-emitting bodies, into her work. Gold can be found in small details like the medallions in Mourning Wreath or in the visual brilliance of Sun, from Hennessy’s emerging artist exhibition in 2019 at the Museum of African Diaspora (MoAD), everybody loves the sunshine.[8]

For that exhibition, Hennessy was inspired by the scattering garden, a dedicated outdoor space designed for the ceremonial scattering of ashes. She transformed the MoAD gallery into a texturally rich landscape for the release of grief. The sun and the rainbow are symbols of renewal and hope that manifest in the sky, accessible from any landscape. Sun, made from gold twist ties, among other things, allows Hennessy to bring the transformative power of celestial bodies into the gallery space.

“I remember my godmother wearing shiny silver rings, and how my grandmother was always wearing a bit of gold—and just being dazzled.” –Angela Hennessy

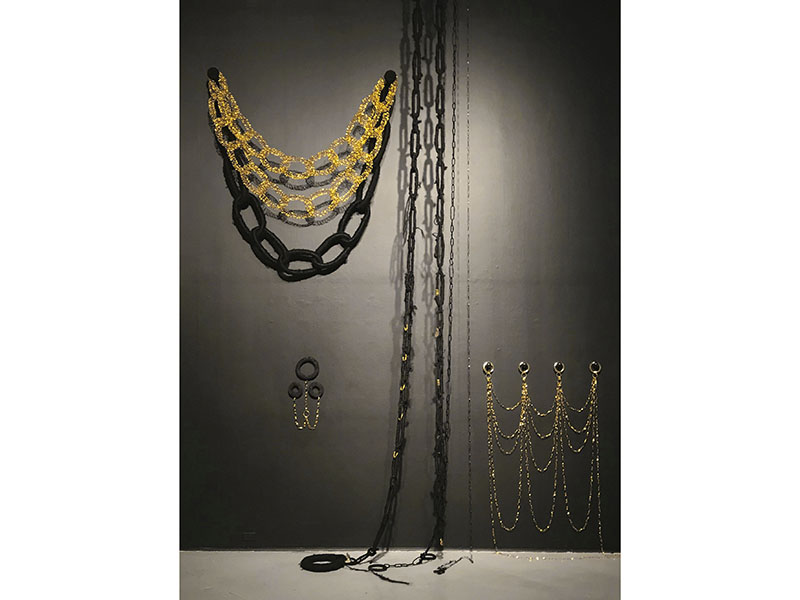

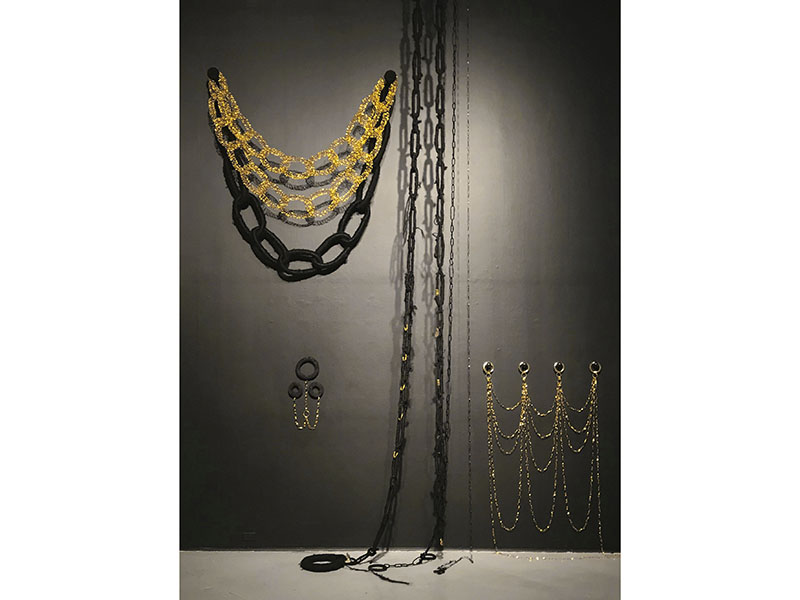

Hennessy uses chains to comment on the Black American experience. They present as physical objects of oppression as well as a cultural symbol of power, success, and dominance within the context of hip-hop. Her piece Bling, included in the exhibition A History of Violence, organized by the Queer Cultural Center, includes the flash of oversized gold chains made with gold twist ties hanging next to chains made of Black hair. Curator Rudy Lemcke states, “the trope of the necklace combined with the work’s references to shackles and collars re-inscribes these forms with beauty and liberatory power. Its meaning is a flash of reflected light, the bling of adornment from the surface of a deep cultural wound.”[9] Much of Hennessy’s work recognizes these cultural wounds, both individual and collective, while creating the space to grieve and, through the recognition of grief, invite healing.

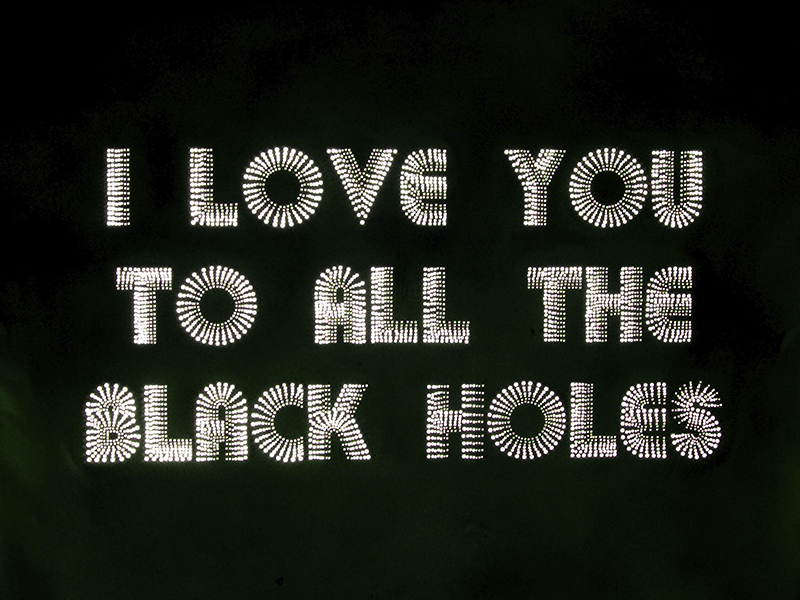

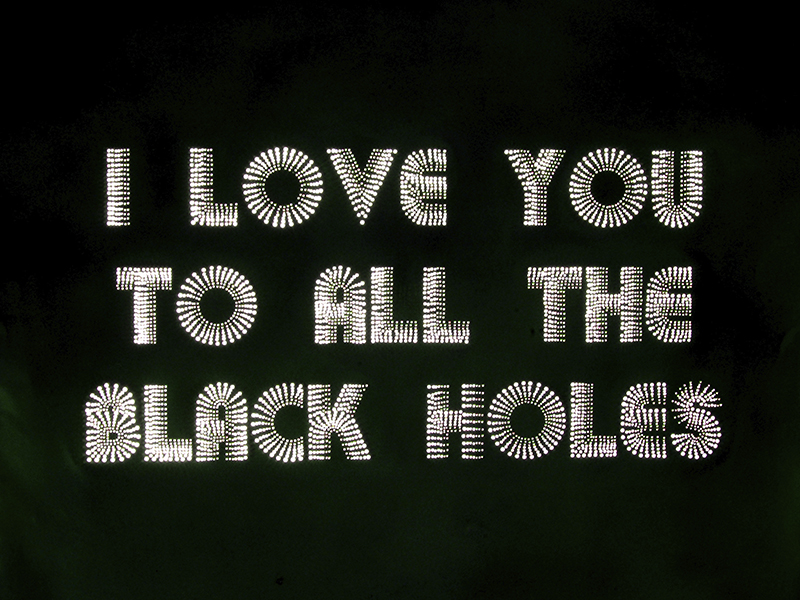

Hennessy’s work utilizes light beyond gold’s flash. LED lights illuminate Black Rainbow from behind and shine through pierced metal in I love you to all the black holes. Light is often used as a symbol of hope and healing, while voids often represent loss and grief. The gravitational pull of black holes is so strong that they trap light. Hennessy was intrigued by the light-absorbing quality of the black velvet from the beginning of that material exploration. In this piece, she honors the voids and illuminates them, providing a message of support.

Sometimes words fail to articulate a felt experience, and objects, try as they might, can fail to represent ideas. No one process or object does all the things necessary to convey the complexities of being human. Hennessy’s art practice includes the physical embodiment of her ideas outside of making. She is verified in the Grief Recovery Method, an activist for the visibility of black women,[10] and a professor who teaches classes about the role of death in art.

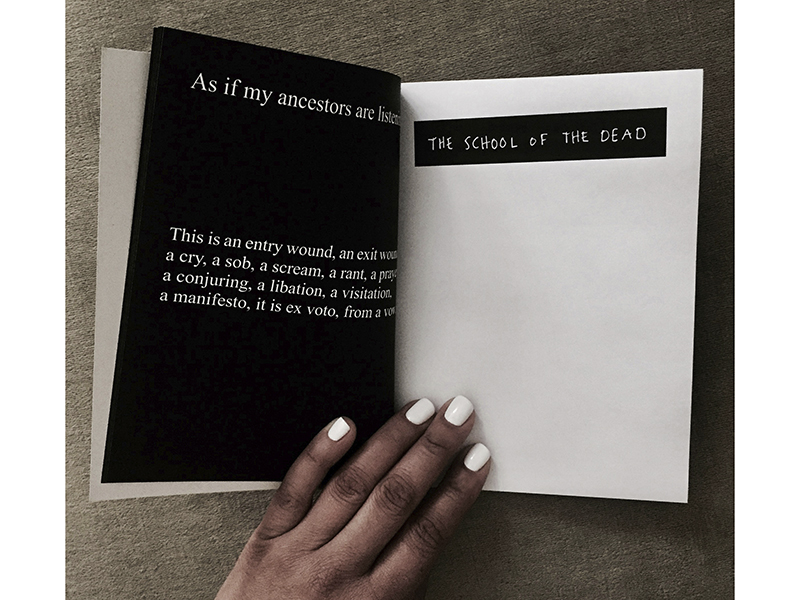

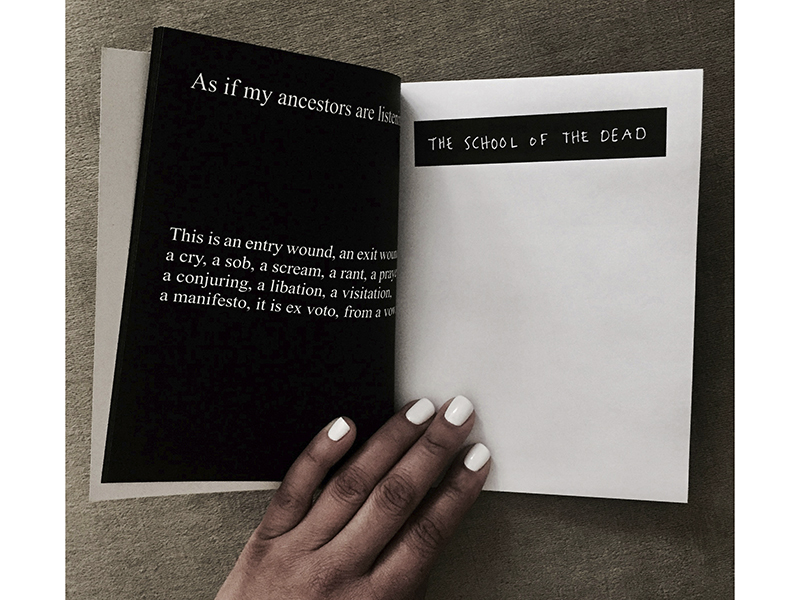

She wrote a manifesto, The Book of the Dead, combining ideas from these roles with her experiences as a survivor of gun violence. Across her work, she is specifically interested in how race features in the understanding and acceptance of the inevitability of death. While coming to terms with one’s mortality is universally human, there is a marked difference for a Black person in America. The violence of slavery, which included the intentional severing of family bonds and the loss of ancestral continuity, caused voids in Black Americans’ heritage. Even now, the continued inequity of the medical system and the violence of the carceral and police states continue to disrupt the stability, safety, and lives of Black Americans, causing incredible pain and loss in both individual families and larger communities.

When Hennessy speaks to an audience, she takes a moment to invite all in attendance to center themselves, then speak the names of their dead. This straightforward grieving ritual is a way to acknowledge those who came before. Simply saying the names of those who have died is a way to bear witness, to recognize their loss to the self and the community, to remember and be remembered as being connected, and to grieve the loss of connection. This ritual acknowledgment of grief and the wound it leaves provides a possibility of healing. This ritual act resonates with the work of Lori Talcott, whose practice is based on the medieval idea that the wound contains the remedy. Both artists incorporate rituals that ask the participant to speak their pain and, in so doing, recognize the source. Hennessy also invites others present to honor the grief of those around them. This brings the presence of the departed into the space and acknowledges the universality of loss.

Hennessy stated pre-pandemic, “the work that I do now is about making space for death and making space for the dead. And a big part of how we do that is by reclaiming these ruptured lineages, the family ties that have been shredded, completely unraveled.”[11] As the pandemic forces conversations about mortality in every corner of the globe, and the violence by American police against Black and brown people continues unabated, Angela Hennessy’s work provides a place for reflection on the reality of loss and an invitation to grieve.

Angela Hennessy’s work will be included in Queer Threads, at the San Jose Quilt and Textiles Museum[12] from April 13–July 3, 2022. The latest version of this evolving exhibition, curated by John Chaich and much delayed by the pandemic, will include artists from the original iteration alongside artists from the region.

Angela Hennessy

La presencia de la Ausencia

Por Rebekah Frank, traducido por Jimena Ríos

,%202017%20800%20x%20600.jpg)

Angela Hennessy, Corona fúnebre (detalle), 2017, pelo sintético y humano, pelo encontrado y pelo de la artista, cobre dorado a ala hoja, pintura esmalte, cadena, marco de alabre, base de cemento, base 267 x 183 x 91 cm diametro, foto de la artista.

Este articulo es el segundo de la serie que se centra en artistas cuyo trabajo bordea la joyería. Para el propósito del articulo, los artistas en este borde la usan materiales, técnicas o temas relacionados con la practica de la joyería. El cuerpo esta presente en el trabajo, no necesariamente como receptor del adorno, pero con la importancia del cuerpo físico en su forma, temática o narrativa. La cercanía de estos artistas a la joyería aporta una perspectiva fresca a quienes estamos inmersos en este campo.

La pandemia global trajo la mortalidad a la mente de todos. La perdida de vidas es incalculable, haciendo que la pena se vuelva familiar, aun cuando la pandemia no permita la conexión física de las practicas de duelo tradicional, ni siquiera sentarse al lado de la cama acompañando a alguien que esta muriendo. En su ensayo “Duelo, Interrumpido”, para el London Review of Books, Jude Wanga habla de la desconexión con el duelo actualmente.

No hay cierre. No hay capitulo final. No hay momentos conmovedores para tomarme de las manos con mis seres queridos y hacerles saber que los ame mientras respiran por última vez. No hay familiares acompañándome por una semana, cocinando, cuidándome, dándome amor y abrazos. No hay abrazos en la iglesia, o en el cementerio. No hay nada. Puede que no haya nada nunca mas. Estoy rota. Soy un disco rayado, un tartamudeo en el tiempo. Esto es un duelo, interrumpido.[1]

Pero el duelo no es nuevo, aunque se practica con más frecuencia en la intimidad y no en escala global. Angela Hennessy procesa a través de su práctica su relación con el duelo como individuo y culturalmente como mujer negra y queer. En su trabajo crea un espacio para el duelo colectivo, un lugar para honrar a aquellos que vinieron antes, donde el espectador es invitado a considerar el significado del duelo.

La joyería de luto Victoriana fue una gran influencia para Angela durante sus estudios de grado en la Universidad de Arte de California, con raíces en su primera etapa de formación como joyera La joyería de luto Victoriana posibilitaba una manera de mantener a nuestro ser querido muerto, físicamente presente y conectado con los vivos, usando pelo para crear objetos íntimos para el recuerdo. La reina Victoria empezó esta moda después de la muerte de su marido, el príncipe Alberto, en 1861, llevando un mechón de pelo de él en un medallón por el resto de su vida. Las piezas de duelo victorianas incluyen pelo largo trenzado en forma de brazalete, tiras de pelo enlazados en colgantes y guirnaldas visualmente complejas con el pelo del difunto en forma de flores y ornamentos rodeando su retrato.

,%202007%20800%20x%20600.jpg)

Mientras Hennessy investigaba esta tradición, descubrió que el pelo tenía un lugar en los rituales de duelo atreves de la historia y las culturas. Una rápida búsqueda en google sobre el pelo y el duelo trae como resultado una gran variedad de prácticas ante la perdida. Los recientes deudos podían afeitarse la cabeza (Nigeria), no afeitarse la barba (Grecia), no peinarse ni cepillarse el pelo (Filipinas), guardar bajo llave un mechón de pelo por un año (Lakota), o usar el pelo para cubrirse la cara (Antiguo Egipto). Lo que fascinó a Hannesy en esta variedad es “como el pelo se volvía un material que nos conectaba con el muerto, a la vez que marcaba la separación causada por la muerte.”

La investigación de Hennessy con el pelo empezó con pelusa. Mientras de construía terciopelo negro separando la pelusa de los hilos de la estructura, reconoció el parecido con el suelo de una barbería de negros después de un corte. Su primera pieza usando la pelusa Blacklets: Una mota de hollín o

suciedad, (A Speck of Soot or Dirt) rinde homenaje a este descubrimiento material y cuestiona su identidad. Después, aplica la pelusa de terciopelo a Velcro tejido en un gran marco oval dorado, creando textura visual y contraste. La forma de Mourning Weave (Tejido de luto) hace referencia al dije tradicional, aquel que podía guardar un mechón de pelo y al marco ovalado de los retratos Victorianos, siempre puestos en el centro de las coronas fúnebres.

Es interesante mencionar que mientras el punto de partida de Hennessy era claramente referencial a la joyería, no tuvo como resultado crear joyas. Hacer arte muchas veces lleva a los artistas por caminos inesperados. Melanie Bilenker es una artista blanca estadounidense cuyo trabajo también tiene raíces en la joyería de luto Victoriana.[6] Su trabajo mantiene conexiones con las técnicas históricas de la joyería victoriana expertamente re imaginadas con materiales modernos. Usa su propio pelo para dibujar escenas domesticas mostradas en medallones, conmovedoramente íntimos y poderosos en su simpleza. El hecho de que Bilenker y Hennessy produzcan un trabajo tan diferente a partir de la misma referencia histórica resalta la riqueza de interpretaciones que llegan cuando se incluyen diferentes voces en las conversaciones del mundo del arte.

Una de las razones de las diferentes exploraciones es que el pelo que Hennessy usa es el suyo, biracial y no lacio, pelo que tiene como agregado un significado cultural. El pelo de blancos tiene el privilegio de ser simplemente una línea. El pelo en el trabajo de Hennessy no es neutral. Es el pelo de negra, de una mujer negra, de una mujer queer negra, pelo biracial. Al usar pelo de negra como material hace referencia a una compleja historia cultural que incluye trauma ancestral y opresión tanto como orgullo, belleza y la celebración de la negritud.

La experiencia personal de Hennessy aporta una narrativa que atraviesa su trabajo. La ausencia y descubrimiento de las conexiones familiares, la lucha por definirse a uno mismo cuando encarnamos diferentes identidades, la contundencia de la muerte de un padre, la experiencia de estar al borde de la muerte, el peso del dolor ancestral sumado a la continua violencia actual contra cuerpos de negros, el duelo necesario por ser negra en Estados Unidos. A través de su búsqueda creativa, genera un espacio para experimentar belleza y enojo, alegría y pena, que pueden coexistir simultáneamente.

Muchas de sus piezas están hechas con tejido de crochet de pelo sintético en tonos que reflejan la diversidad de su familia, combinado con su propio pelo. Arcoiris negro (Black Rainbow) y Atardecer de un sol negro (Setting of a Black Sun) son grandes esculturas hechas con crochet a través de la repetición de pequeños aros de pelo entrelazados. Su cualidad de macramé refleja la nostalgia de Hennessy por su niñez, creció en un pequeño pueblo en el norte de la costa de California en los 70´s. Ella se refiere al proceso de tejer al crochet como una manera de mantener juntas a las cosas, un acto meditativo de conectar físicamente sus diferentes historias raciales, la disrupción de su familia de origen, las capas de pena conectadas con una existencia en este mundo que considera tu presencia como una alteridad.

Gran parte de la practica de Hennessy reconoce la vaguedad del duelo, el anhelo por cosas desconocidas y difíciles de nombrar. Objetos de duelo no identificados (Unidentified Grieving Objects) presenta sogas colgadas desde el techo hechas de pelo sintético rubio y negro interrumpidas por pufs voluminosos en la exposición de 2017 Cuándo y a dónde yo entro (When and Where I Enter), en la galería Southern Exposure (SoEx) de San Francisco. La monumental Corona fúnebre Mourning Wreath lleva la tradición de las coronas Victorianas a la pared, sostenido por una sola columna de acero que invita a acercarse de los dos lados dejando todo a la vista. Esta saturada de festones de pelo sintético trenzado, tejido y meticulosamente arreglado. Medallones de cobre dorados a la hoja cuelgan de cadenas desde lo alto de la corona hasta el centro.

El efecto visual de estas piezas relacionándose unas con otras en es notable, los tonos de oro con los matices de rubio a marrón y al negro montados contra las paredes negras de la galería. Pintar las paredes blancas, sugerido por la curadora y aceptado por Hennessy, fue una manera subversiva y efectiva para alterar el cubo blanco. Hennessy había mostrado sus piezas individuales previamente sobre paredes negras, pero montado en lugares con paredes blancas. El trabajo de Hennessy pide repensar sin remordimientos la blancura del mundo del arte Al pintar la galería de piso a techo, ella marca un giro en las expectativas para un espectador familiarizado con la experiencia típica de las galerías y desafía el blanqueo dentro de los espacios de arte.

,%202017%20800%20x%20600.jpg)

La manipulación del pelo como material de Hennessy es seductora. Ella trata el pelo como si fuera un textil con textura lujosa y una tacto visceral, perfectamente peinado y arreglado en formas monumentales, apartado e iluminado con belleza. La etiqueta del arte niega al espectador la satisfacción de tocar las esculturas, negando también el deseo privilegiado de tocar pelo de negros y con esto otorga poder, sentido de propiedad y dominación sobre el cuerpo de los negros. La pieza de neón Perra, no toques mi pelo (Bitch, Don’t Touch My Hair) de Tiff Massey, fue hecha como autorretrato, pero como ella dice, habla de todas las personas de color con pero enrulado,[7] inequívocamente mostrando la falta de respeto inherente a esta esta invasión al espacio de alguien. La tensión entre el deseo de romper el muy olvidado tabú de tocar los rulos negros y la negación del deseo debido a la etiqueta en lo que ha sido tradicionalmente un espacio de blancos es poética.

Mientras que el pelo es el material principal con el que Hennessy trabaja, no es el único. Distribuye oro en su trabajo tanto a la hoja como en formas que lo simulan en distintas cantidades como referencia a su interés por la joyería.

Incluir este material llama a reflexionar sobre el concepto de valor, y también el lenguaje visual de la luz y la luz que emiten los cuerpos, en su trabajo. El oro puede encontrarse en pequeños detalles como el los medallones de Corona Fúnebre o en el resplandor visual de Sol, de la exposicion de Hennessy como artista emergente en 2019 en el Museo de la diaspora africana (MoAD), todo el mundo ama el sol (everybody loves the sunshine).[8]

Para esa exposición Hennessy se inspiró en los cementerios parque, un espacio exterior dedicado a la ceremonia de diseminar las cenizas. Transformó el MoAD en un paisaje rico en texturas para liberar el dolor. El sol y el arcoíris son símbolos de renovación y esperanza que se manifiestan en el cielo, accesibles desde cualquier paisaje, Sol, hecha a través de lazos torzados, entre otras cosas, entre otras cosas permite a Hennessy traer el poder transformador de los cuerpos celestiales al espacio de la galería.

“Recuerdo a mi madrina usando anillos de plata brillantes y como mi abuela siempre usaba algo de oro y como yo esta totalmente deslumbrada”

Angela Hennessy

Hennessy usa cadenas para hablar sobre la experiencia de los Negros de Estados Unidos Las cadenas son presentadas como objetos físicos de opresión tanto como símbolo cultural de poder, éxito y dominación en el contexto del hip hop. Su pieza Bling, incluida en la exposición Una historia de la violencia (A History of Violence), organizada por el Centro Cultural Queer, muestra el destello de cadenas a gran escala hechas con tiras de oro en torsión colgando al lado de cadenas hechas con, pero de negro. El curador Rudy Lemcke dice, “El símbolo de la cadena combinado con la referencia a los grilletes y los collares re inscribe esas formas con belleza y poder de liberación. El significado es un destello de luz reflejada, el brillo de los adornos desde la superficie de una profunda herida cultural”[9] Mucho del trabajo de Hennessy reconoce estas heridas culturales, tanto individual y colectivamente, creando un espacio para hacer el duelo y a través del reconocimiento del dolor invita a sanarlo.

Angela Hennessy, Te amo hasta todos los agujeros negros, 2014, objeto, placa agujereada de cobre, pintura acrílica, panel de LED, marco 41 x 51 cm foto de la artista

El trabajo de Hennesy utiliza luz mas allá del destello del oro. Luces de LED iluminan Arcoiris negro (Black Rainbow) desde atrás y brillan a través de metal agujereado en Te amo hasta los agujeros negros I love you to all the black holes. La luz se usa en sus piezas como símbolo de esperanza y sanación, mientras que el vacío se representa como perdida y dolor

La atracción gravitacional de los agujeros negros es tan fuerte que atrapan la luz. Hennessy estaba intrigada desde que empezó su investigación por los materiales por la cualidad del terciopelo negro de absorber la luz. En estas piezas ella honra los vacíos y los iluminarlos, dando así un mensaje de apoyo.

,%202018%20800%20x%20600.jpg)

A veces las palabras fallan para expresar algo que sentimos, y los objetos hacen lo que pueden y pueden fallar para representar ideas. Ni el proceso de nadie ni el objeto puede hacer todo lo necesario para comunicar la complejidad de ser humanos. la practica artística de Hennessy incluye la personificación de sus ideas fuera del hacer. Ella es parte del Meto para perdidas emocionales, una activista de la visibilidad de las mueres Negras, y una profesora que enseña sobre el rol de la muerte en el arte.

Escrbio un manifesto El libro de los muertos (The Book of the Dead), combinando ideas de estos roles con el de ser una sobreviviente de la violencia armada. A través de su trabajo esta especialmente interesada en como ka raza tiene un rol en a comprensión y aceptación de la muerte como algo inevitable. Mientras que aceptar nuestra mortalidad es universalmente humano hay una diferencia marcada para una persona negras de Estados Unidos. La violencia de la esclavitud, que incluía el corte intencional de lazos familiares y la perdida de la continuidad ancestral, causó vacíos en la herencia de la américa negra. Incluso ahora, la continuidad de la inequidad en el Sistema medico y del sistema carcelario y policial sigue siendo disruptivo para la estabilidad, la seguridad y la salud y la ida de los negros americanos causando un dolor inevitable y perdidas tanto en familias individuos como en comunidades más amplias.

Cuando Hennessy habla en publico, se toma un momento para invitar a los presentes a centrarse, después les pide que digan el nombre de sus muertos. Este ritual de duelo directo es una manera de reconocer a quienes vinieron antes. Simplemente diciendo los nombres de aquellos que han muerto es una manera de dar testimonio, de reconocer su perdida para nosotros mismos y para la comunidad, para recordar y ser recordados por haber estado conectados, y para duelar la perdida de la conexión. Este ritual de reconocimiento de la pena y la herida nos da una posibilidad de sanación. . Este acto ritual resuena con el trabajo de Lori Talcott, cuya practica esta basada en la idea medieval de que la herida contiene el remedio. Las dos artistas incorporan rituales que piden al participante que hablar de su dolor y al hacerlo reconocer el origen. Hennessy también invita a otros a honrar la Perdida de quienes están en su entorno. Esto trae la presencia de quien se fue y reconoce la universalidad de la Perdida.

Hennessy dijo antes de la pandemia “el trabajo que hago ahora se trata de hacerle espacio a la muerte y hacer lugar al muerto Y gran parte de como lo hago es recuperado el linaje roto, los lazos familiares que han sido destrozados, completamente desarmados” Mientras la pandemia impuso la conversación sobre mortalidad en cada esquina del mundo y la violencia de la policía estadounidense contra personas negras y marones continua creciendo, el trabajo de Angela Hennessy aporta un lugar de reflexión sobre la realidad de la perdida y una invitación para el duelo.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2021/february/grief-interrupted.