How adept is contemporary jewelry at negotiating a world in flux? Making the most of flux requires fluidity, an ability to embrace movement and change with ease and grace. The opposite of fluidity is fixity, a quality that, in the globalized world contemporary jewelry now inhabits, represents a stubborn clinging to place, a refusal of the possibility of belonging everywhere and thus nowhere specifically. In a time when fluidity is prized, what value can a commitment to fixity have for contemporary jewelry practice?

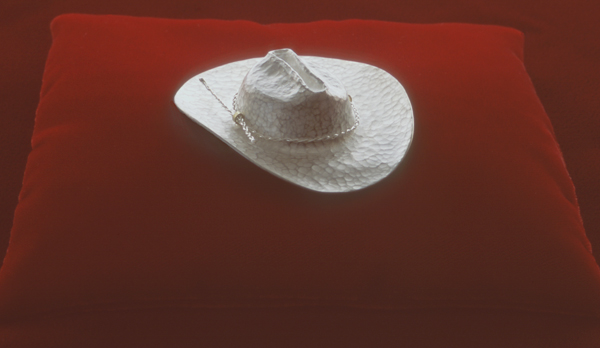

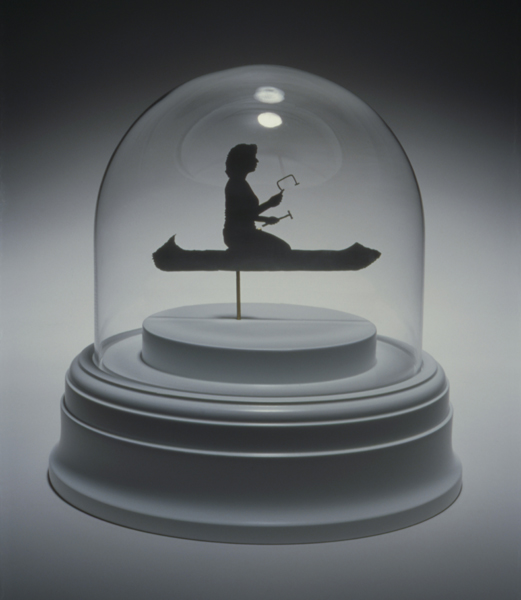

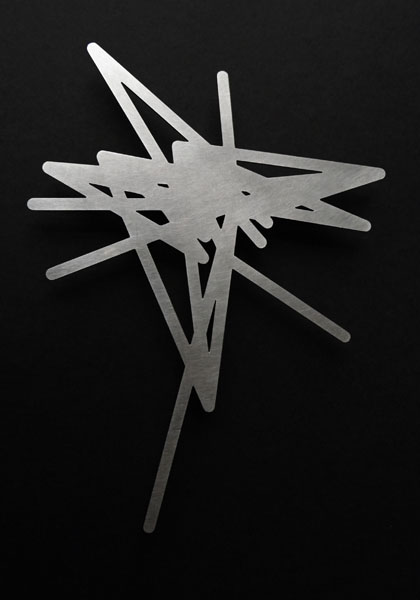

Searching around for recent jewelry that might represent flux, I came across Otto Künzli’s Himmel brooches, which are based on maps of airline routes. The German word Himmel means both sky and heaven, so it is at once a physical and metaphysical location. As Künzli puts it, ‘In our Himmel you can find aircraft and clouds and skyscrapers but also angels and dreams and ancestors.’ (Künzli 2011) And this, which also seems important: ‘Although my brooches are based on the maps of airlines it is after all not important to recognise particular routes and I do not support any speculation in that direction . . . Instead I wish and hope that my brooches evoke imaginative journeys to fantastic, wonderful, inner and outer places and realms.’ (Künzli 2011)

Künzli’s brooches celebrate new constellations generated by a condition of being endlessly on the move, in transit. These brooches are literally nowhere, floating outside of place. They are a perfect sign for the globalized, freewheeling, de-territorialized jewelry practice which, I think, is contemporary jewelry’s most celebrated response to a world in flux.

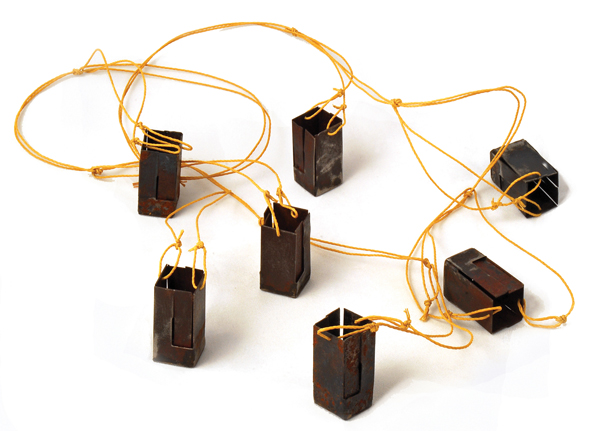

Like a geologist taking a core sample, the wearer/owner of the ring literally digs their jewelry into the ground to gather a piece of the earth from the place that matters most to them. Earth Ring belongs to the same modern world of mobility as the Himmel brooches, since it assumes the wearer will be in transit and thus need to take a relic of home with them. However it doesn’t revel in a state of nowhere-ness and it seeks solutions for remaining connected to place in spite of all the movement. If Künzli specifically asks that we refuse region or place when considering his brooches, Freeman makes place and region – through soil, the very earth itself – critical to the meanings of his ring. Here, fixity stands in contrast to flux.

Stories of Art (Jewelry)

So let me be a little controversial and suggest another way to articulate the difference between these two jewelers. Otto Künzli is a Swiss contemporary jeweler living in Munich who makes contemporary jewelry. Warwick Freeman is a New Zealand contemporary jeweler living in Auckland who makes New Zealand contemporary jewelry. Künzli, in other words, doesn’t need a qualifier to define and locate the kind of jewelry he makes, whereas Freeman does. Saying this is to say that the global, freewheeling, de-territorialized jewelry practice has come to seem universal, while the local or regional jewelry practice has come to seem the opposite.

The standard story of art is the story of ‘how western art progressed from archaic symbols to highly naturalistic styles, and then how modern artists turned away from naturalism and became skeptical of the world of appearances.’ (Elkins 58-59) It runs basically like this: 1) Egypt and Greece, where human proportions were studied mathematically; 2) the near-loss of that knowledge in the Dark Ages; 3) the rediscovery of classical knowledge in the Renaissance; 4) the elaborations of baroque and rococo; 5) art turning against its naturalistic heritage with modernism. Because western art is unique in its pursuit of naturalism, or at least the vigor with which it pursues this goal, naturalism becomes the story of western art. And because the sequences of western art history shape all art history, all art production is compared with the standard story, no matter how inappropriate this might be.

Does art history also propose a dominant narrative for the history of contemporary jewelry? After comparing as many historical accounts of contemporary jewelry as I could get my hands on, I would say the answer is yes. What I identify as the standard story of contemporary jewelry is best captured in Peter Dormer and Ralph Turner’s book The New Jewelry: Trends + Traditions, published in 1985. Let me briefly show you how the story unfolds.

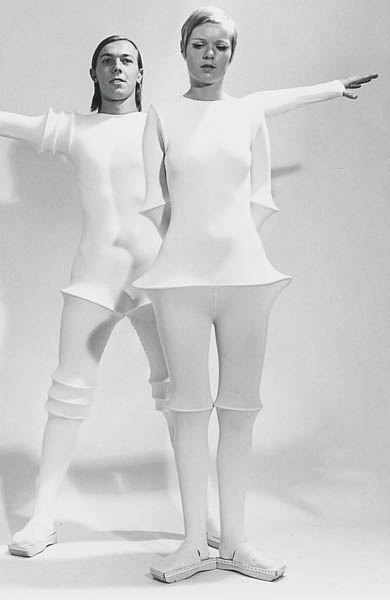

Dormer and Turner then move to the Netherlands and the jewelers Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum, who not only introduce new materials such as aluminum but also connect contemporary jewelry to its cultural moment and encourage it to become more democratic. The story stays in the Netherlands with B.O.E., a revolutionary movement reacting against the ‘dominant clinical approach’ of the Dutch Smooth style.

Then comes Britain, as a result of the stimulating exchange that developed between Dutch and British jewelers in the late 1970s. The major claim to fame here is the movement towards ‘wearables’ in the work of people like Susanna Heron and Caroline Broadhead.

At this point, the authors can define the new jewelry as a movement emerging from Germany, the Netherlands, Britain, Austria and Switzerland. It is characterized by ‘a desire to avoid clichés in design; a desire to make exciting, robust and, where possible, cheap ornament; a desire to make adornment that can be worn by either sex; a frequently expressed distaste for jewelry which is vulgar and merely status-seeking; and always an interest in ensuring that the ornament works with and complements the wearer’s body.’ (Dormer and Turner 14)

Now Dormer and Turner introduce contemporary jewelry from America, making clear that it embodies some significant differences from what’s happening in Europe. ‘In the United States,’ they write, ‘the current tendency is to regard jewelry as mini-sculpture rather than wearable ornament which has to be worn in order to be seen properly.’ (Dormer and Turner 14)

Dormer and Turner’s historical narrative concludes with Italian jewelry, which fits nicely at the end. Important Italian jewelers have also been sculptors, which connects neatly to the jewelry versus art issue that is central to American work. Italian jewelry is very distinctive, like America, but links to European minimalism – even if it isn’t quite as radical as what’s happening in other parts of Europe.

This narrative is contemporary jewelry’s standard story, its equivalent to the struggle towards naturalism in western art. The core of the story is not a search for realism, but the critique of preciousness and the struggle to liberate jewelry from restrictive notions of value, so that it becomes available for artistic expression and experimentation, a deeper engagement with society, and a new awareness of the body and the wearer. Schematically it appears like this: 1) Germany, with traditional goldsmiths introducing artistic expression into their work; 2) the Netherlands, with the socially and materially radical experiments of Dutch Smooth; 3) New Jewelry emerging through the fusion of Dutch and British jewelers; 4) American and Italian jewelry, as alternative traditions with varying relationships to European jewelry; 5) the new jewelry spreading around the globe.

If you were updating Dormer and Turner’s book you would add a section about the dissolving of differences between European and American jewelry, the end of America’s idiosyncratic jewelry tradition as it becomes part of the mainstream thanks to greater contact with Europe. It would also be necessary to discuss the emergence of a new kind of global jewelry in the last ten or fifteen years, a product of the internet age and the internationalization of the contemporary jewelry scene, in which regional differences largely disappear. But the critique of preciousness would still serve as the best structuring device for the narrative. In the 25 years since The New Jewelry: Trends + Traditions was published, no other story with the same force has emerged. All contemporary jewelry historians tinker with this basic narrative.

Europe Versus America (and the World)

Dormer and Turner describe the axis of their book as being ‘European-American’ and they suggest that the reason is because, ‘on the whole, the new jewelry that is produced outside western Europe and the United States is derivative from it.’ (Dormer and Turner 20) Yet they don’t seem to notice that their axis is unbalanced. The countries that the authors identify as making good work, such as Canada and Australia, on the whole look to Europe, not America. Canada’s 1983 exhibition Jewelry in Transition was inspired by Jewellery Redefined, an exhibition of European work held in London in 1981. Australia has strong links with Britain and Europe and the visitors heading Downunder are mostly European: Hermann Jünger, Claus Bury, David Watkins, Otto Künzli and so on. It’s not that American jewelers don’t visit, just that they don’t have the same impact.

In many historical accounts America fits awkwardly into the standard story of contemporary jewelry. It is notable, for example, that Fritz Falk and Cornelie Holzach can tell the story of contemporary jewelry in their book of the Schmuckmuseum’s collection and never really mention American jewelry. According to this view, nothing critical to the development of contemporary jewelry happened in the United States. Imagine reversing the situation. Could a plausible narrative of contemporary jewelry be written in which Europe was similarly overlooked? A book telling the story of contemporary jewelry that is mostly filled with American jewelers and a sprinkling of European, Japanese and Australasian makers would not act as a valid account of contemporary jewelry. It would be a regional history and it would probably require the qualifier of ‘American.’ The point is that there is no requirement to deal with the whole world to tell contemporary jewelry’s story. The standard story of contemporary jewelry is in fact the story of European jewelry. This local narrative becomes an international one and as a repository of the best European jewelry, the Schmuckmuseum is, de facto, a world institution, even if most of the world is in fact missing.

Some of my thinking about these issues has been shaped by the work of political scientist Dipesh Chakrabarty, who speaks about the challenges of ‘provincializing Europe.’ As he suggests, ‘Third-world historians feel a need to refer to works in European history: historians of Europe do not feel any need to reciprocate.’ (Chakrabarty 1992, 2) While European historians can produce their work in relative ignorance of non-western histories and this has no discernible effect on the quality of what they do, the same is not true for non-western historians. If they chose to ignore western histories and theoretical terms, they appear outdated or old-fashioned. You’ll recognize this condition in relation to contemporary jewelry discourse.

This situation, says Chakrabarty, is not just a result of cultural cringe on the part of non-western people, or cultural arrogance on the part of Europeans. Instead, it emerges from the social sciences themselves, which are founded on the notion that only European history is theoretically knowable – which is to say, only European history produces the fundamental categories that shape historical thinking, whereas all other histories are about empirical research that fleshes out the skeleton of knowledge generated by Europe. The social sciences are founded on the idea that Europe represents an achievement of maximum development and sophistication and all other histories will be understood by their difference to the European model. Everyone else is left with the project of ‘positive unoriginality’, in which the basic models have already happened in Europe and await to be imported and identified in local contexts.

What does this mean for contemporary jewelry? Under the current framework, European jewelers make contemporary jewelry, while American jewelers make American contemporary jewelry. This points to one of the things at stake in revealing the Europeanness (the regional quality) of European jewelry discourse: it is a matter of undoing exclusion and introducing equality. Another reason to care is that, by revealing the discourse as regional, we can undo the pretend universality of European jewelry. The story of contemporary jewelry cannot be told by reference to Europe only, as what happens in other places – the uneven development – is a central part of the history of the practice.

An example: one of the reasons that Dutch jewelry from the 1960s appears universal is because it seems like a complete and proper expression of the critique of preciousness. (New materials, a democratic intention, the freedom to experiment.) But it only seems complete because the full story of what the critique of preciousness entails is obscured.

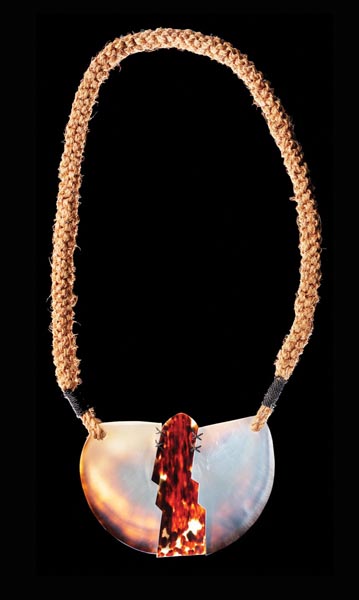

When you bring in the strange form that the critique of preciousness took on in New Zealand, say, Dutch jewelry stops seeming universal and starts seeming like a regional expression of this investigation or theme. It becomes one way of tackling it amongst many, rather than the only or most important way against which all other explorations of the critique of preciousness must be compared.

Ambition and the Local/International Binary

The problem of the standard story of art and the binaries that it throws up is something that art history is grappling with across all forms of visual art. The difficulty is that binaries have an awkward way of surviving attempts to disrupt them. It is relatively easy to swap values, so that, in our case, American jewelry becomes dominant and European jewelry becomes the submissive partner, but doing this leaves the power structure intact. As Hegel noted about the master-slave relationship, the slave doesn’t just have to free themselves, but they have to free the master too. In other words, liberation is about disrupting the hierarchy, not just reversing it. American jewelry doesn’t just have to free itself, but it also has to liberate jewelry from the rest of the world, as well as Europe.

If this talk were a play, all the critics would comment on a disappointing third act, in which the early promise of the script is unrealized. I wish at this point I could unveil some brilliant proposition that would solve the problem, but I am just as stumped as anyone else who thinks about these issues. I’d like to finish this talk with what is a rather modest proposal to rethink the binary of local and international by suggesting that the two terms do, within ambitious jewelry, interact in a dynamic way.

Whether operating in a state of flux or a state of fixity, ambitious jewelry works to establish itself as part of an international jewelry discourse. It is neither provincial nor parochial. It is aware of the wider world, of the larger global scene to which it belongs. What I am calling ambition is really the ability of a jeweler to take the values of contemporary jewelry and remake them in terms of their own cultural situation. Everyone does this – and anyone can do this, which means the field is open, and all that matters is how well you do it. We are very familiar with how globalized, freewheeling, de-territorialized jewelry practice does this, but we are less agile at reading the same dynamic in contemporary jewelry that appeals to place.

The particulars in this case are not necessary to experience the ambitions of the jewelry, which relate to the engagement with materiality that is one of contemporary jewelry’s special capabilities. In an artist statement written for Schmuck 2011, the international exhibition held in Munich, Castanon defines his investigation in terms of absence, of cavities and containers that are inhabited by mute presences. As he puts it, ‘I rescue objects and materials that were on the way to oblivion and come back to communicate a minimal story.’ (Castanon)

Her work emerges from the encounter of two things: contemporary jewelry, which she would define as a critical studio craft practice which makes objects that are grounded in an awareness of the body; and Maori systems of knowledge, which place people in specific relationships to each other and to the world and which sometimes use objects to mediate these connections. The strategies of international contemporary jewelry are essential in this process and the fact that Wilkinson applies them to a very specific, local problem that will not be of relevance to most of the rest of the world, doesn’t mean that her practice is provincial or in any way opposed to the international.

One of the most dynamic aspects of her work is the way it traffics in questions of social relations and networks. Within the practice of surface archaeology, this is expressed by her willingness to make outside the studio, working on park benches or picnic tables, for example, so that the process of making is available to the wider public that is using the same spaces from which her raw materials are collected. Her project Seeding the Cloud: A Walking Work in Process, structures the duration and distance of the walk by how long it takes to create a necklace from found plastic and fake pearls on a string of a pre-determined length. The necklace is made in public, using a drill and other equipment that Bartley carries in her bag.

It’s easy to think of such a detailed focus on the local as being a kind of dead-end, a fast track to myopic vision and yet Bartley’s practice gives serious thought to the big questions facing contemporary jewelry – specifically, its future as a practice in a world where the relevance of contemporary jewelry is constantly – and rightly – questioned. In her desire to engage deeply with specific places, Bartley articulates a strong claim about contemporary jewelry’s place within the relational turn that characterizes recent contemporary art and culture and suggests a way out of the ghetto that is the ultimate destination of craft’s love/hate relationship with fine art. The critique of preciousness is turned outwards again, refreshed as a tool through which contemporary jewelry can engage with the wider world. If the international is critical for ambitious jewelry that locates itself in the local, as I hope I have shown, we shouldn’t forget that the local might also offer something important to ambitious jewelry that chooses to de-locate itself in the international.

The Destination and the Journey

Now I have to confess that I read Ravenhill’s article while sitting in Air New Zealand’s business lounge at Heathrow airport. I love being pampered as part of the highly mobile global elite. And yet I still want to finish my talk by asking how this might be relevant for contemporary jewelry. So much of the contemporary jewelry scene feels like an airport business lounge, where the same people circulate from event to event, and the jewelry, while of very high standard, could in fact be made anywhere. I’m the first to admit that it’s very nice in the lounge, but what are we giving up by sealing ourselves off in the nowhere-ness of the airport, prioritizing the journey rather than the destination? To return to where I started, what do we gain when Künzli’s Himmel brooch and its celebration of the potential of travel is placed alongside Freeman’s Earth Ring and its reminder that everything falls back to earth – to a specific place – eventually.