November 2, 2019–January 26, 2020

Museum Arnhem, Arnhem, the Netherlands

Jewelry and fashion, worn on the body, can express concerns about issues in our society. It seems that, lately, many of these issues are about that body itself. A hairy skin ring, a brooch of cast labia, and many less explicit specimens are on show in the Netherlands. The exhibition Body Control assembles the current perspectives.

Curator Anne-Karlijn van Kesteren has a background in fashion. Body Control presents fashion and jewelry, made by almost 100 designers and contemporary jewelers from all over the world, together. She and her advisor, designer Frank Verkade, noticed that many young makers address significant issues:

- Is everyone granted equal freedom over what to do with their bodies?

- Should we tweak our healthy bodies for the sake of some transient beauty ideal?

- If we glance into the future, to what extent do we want technology to take over our bodies?

Here, the generation of digital natives is itself questioning the blessings of wearable tech. We are probably hybrids or cyborgs already if we go with Bart Hess’s EXT. from Device People: the macabre hairs protruding from strings of sensual data cable sketch eery implications.

RELATED: Eveline Holsappel on Beauty of the Beast, at Arnhem

RELATED: Critical Design Theory in Contemporary Jewelry

RELATED: Lauren Kalman on But If the Crime Is Beautiful

Everything in this exhibition is recent, or at least made after the year 2000. Instead of being sifted from the vast holdings at Museum Arnhem, most works were freshly scouted from the artists themselves. Besides many new names—two artists haven’t even graduated yet—there are also renowned makers. Katja Prins has been exploring the theme of medical possibilities for quite some time already. Her work is present with Hybrids and Offspring, made from medical composites and looking like objects used in an operation room. By Ruudt Peters’s hand, there are three bundles of Lingams. These phallus shapes stand for fertility; not every phallus has a sexual meaning. A Beauty Mask resembling Queen Nefertiti, by Ted Noten, has holes so you can inject fillers in the right spots to look like this ideal beauty.

The parade of experimental body-related works fills an entire church building (which serves as a temporary exhibition space while the main museum is under construction). Showing jewelry and fashion on equal footing offers a nice variety of large and small objects. Upon entering, you’re invited into a first space confined by high curtains, so you get no overview of all that awaits in the glass cases, floating in transparent baubles and on bare pedestals. Yes, many works are shown without any protective covering! It’s not often that you can touch the objects in a museum—if only your conscience wouldn’t forbid it.

A lot of thinking has gone into those curtains, printed with images of skin with hairs and tattoos. They partition the abundance of objects and soften the stark church interior, but that’s only one function. Van Kesteren explained that she didn’t want to present the jewelry statically sitting on a gallery shelf. On a mannequin was no option, either. Nor did she want photos of the object on the body near a piece; in her opinion, that would distract. It was then decided to reference the body in these specially designed curtains. I wouldn’t have noticed it if I hadn’t been told. To me, the exhibition looked not static but dynamic, with objects on different levels. But I missed information to give each piece context until I tapped into the second layer of information: the exhibition booklet or, even better, a phone app that scans a symbol next to each exhibit. This is where you’ll find an explanation of the artist’s concept, always put in the form of a question to involve the visitor. Moreover, and this is essential, it provides images and videos of the object being worn.

Quite a number of objects resemble surgical constructions. There were the metal corset-like posts of Jennifer Crupi’s Ornamental Hands, which force the female hand into a supposedly universal, graceful gesture. Lauren Kalman’s Devices for Filling a Void present medical props that don’t help the body at all, but make it uncomfortable. Ewa Nowak’s Incognito is a shiny construction placed on the face to prevent facial recognition from infringing on your privacy. With Deus Ex Machina, Ashley Jung designed connected finger jewelry that impedes movement, just as technology will curb our freedom even though it seems like we’re in control. These four artists arrived at a similar visual language from very different starting points. Just the sight of these pieces worn makes you feel the cramping of your own fingers or causes you to start drooling as if it’s your own mouth propped open. And it’s then that the piece starts talking to you. The constant retrieval of information made me aware of my own body, my head nervously shifting from the exhibit to the app on the phone in my hand and back. But I took a deep breath and continued to check the information.

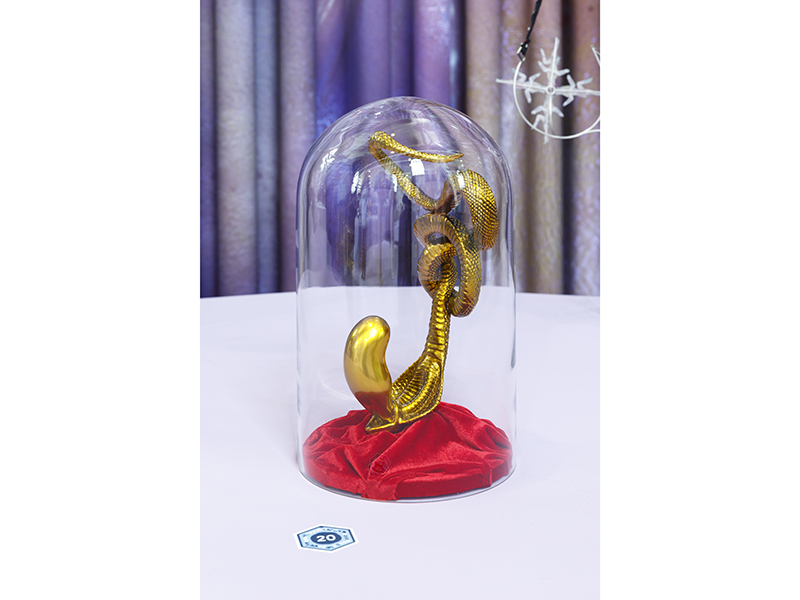

Serpent Mouthpiece, by Frank Verkade, meant for the mouth as well, is even more spectacular when shown worn in the app. Without judgment, it imagines the (inevitable?) symbiosis between organisms and between man and technology. Another mouthpiece is Ruudt Peters’s depiction of the soul as a last breath of silver and glass. Burial practices, with coins or objects in the mouth of the deceased, come to mind. There was more jewelry of the invasive kind in Body Control, a lot of it less subtle than this. The climax in this genre was a gold cobra with an insertable, vagina-filling part. Leanie van der Vyver sees pop icons such as Miley Cyrus and Nicki Minaj spreading their legs and showing more naked flesh with every show. To draw even more attention to the groin in a future performance, this snake jewelry could be the next step—unless the singers’ bravado stops at penetration.

Skin is another abundantly present thing in this exhibition, from the pink porcelain used for doll limbs (Marion Delarue), to pantyhose and polymer (Iris Eichenberg) and human parchment (Sruli Recht). The hairy skin on Recht’s unique ring was taken from a strip of the designer’s belly. Video proof of the operation comes with it, as shown in the exhibition app. Why did he deliberately blur the lines between the body and the adornment? Understandably, this piece sparks an almost physical reaction, but what is it other than a spectacular stunt? Some objects are activist in a subtle way, others are in your face but forgotten once you’re on your way out of the show. Some good causes seemed a bit far-fetched, for example. What to think of Perspire? I was immediately drawn to the pair of pointe shoes, beautifully overgrown with crystals. As it turned out, the artist, Alice Potts, had assembled her own sweat, and the minerals were grown from excreted salts. According to the exhibition booklet, there’s a taboo on sweat that we need to talk about. Is there? Do we? Is this immaturity, or is the artist misunderstood? Likewise, the stir about female nipples being banned from social media when male nipples aren’t (as evidenced in Censorship Device, by Daniel Ramos Obrégon) made me shrug: Differences between men’s and women’s physiques can’t be erased. And it’s kind of comforting that social media come with an algorithm to filter out gross content. But then, in the days after seeing the exhibition, the question “why?” kept popping up in my mind. Could it be that this artist felt powerless against a biased system? I suddenly hoped that the people designing these algorithms are as diverse as possible, since we’re judged by their cultural notions.

A bunch of small copper anchors, hanging low on a chain, looks like cuddly pubic hair. But Nanna Melland’s anchors are no anchors—they’re the IUDs of 200 different women. Something as beautiful as giving birth is overshadowed by the need to control fertility—that’s the reason behind the work. A neckpiece called Judgements, by Katia Rabey, consists of necklaces of increasing lengths, each pendant reading a more accusatory word: prude, tease, askingforit, slut.

The power over one’s own sensuality is at stake here. It’s everywhere throughout the exhibition: the body political seriousness. After seeing so many pieces, it feels as if the artists are outwitting each other in this game of revealing hypocrisy. Is there still room for ambiguity? Aren’t sensuality and lightheartedness always part of the equation as well? But then I stopped in front of three quirky brooches of race cars with cast labia on them. It turns out that Vicky Kanellopolous’s Don’t Be a Pussy, Hop In! is the result of an activist project to help women become more secure about the appearances of their vulvas. When the standard seems to be set by polished porn and Photoshop, and when labiaplasty has become the fastest-growing cosmetic surgery procedure, it’s good to realize that there’s a whole palette of labia possible and normal. The curators most likely had a choice, since several artists, inside and outside jewelry, have translated ordinary women’s vulva parts into art works. But why a race car? Here Kanellopolous lost me, but I do like the playfulness that bridges gravity and fun. (And I researched it later, after leaving the show: Kanellopolous used the device of a race car because “the body is a vehicle,” and to invite men into taking a first look.)

Museum Arnhem hasn’t often shown jewelry lately. There was an exhibition on taxidermy that included jewelry, but that was five years ago already. And now there’s Body Control. Body Control isn’t just an easy anthology, but a well-researched presentation of things happening now. The lineup introduced me to many, many inquisitive makers. However, one more strict round of selection would have made it more manageable. The app provided good information, but having to fiddle with booklet and phone grew tiresome. In Body Control, the perpetual dilemma of staging jewelry with or without the body has not been solved. But if van Kesteren gets her way in presenting this kind of critical jewelry more often, Arnhem may well be a place to watch.

Notes: The photos that are viewable in the museum’s app can be seen at https://www.museumarnhem.nl/de-kerk/kunstenaars-body-control/. You can also find a well-made four-episode podcast series in Dutch, with curator Anne-Karlijn van Kesteren and artists Katja Prins, Charissa van Dijk, and Ted Noten at https://www.museumarnhem.nl/de-kerk/podcast/.