Lisa Walker, The End

February 25–April 4, 2016

Galerie Biro, Munich, Germany

1.

While entering the small gallery space, what I first noticed was how the walls had been spray-painted in a sky-like light blue color. The stains of paint, and square boxes with jewelry pieces hung on the wall, tied the exhibition together in a poetic display. Knowing some of Walker’s work from before, I had expected a more abrasive exhibition with colorful jewelry in strange materials, but the pieces and the display actually felt soothing to me and appeared as an invitation to contemplate the work in a civilized manner. On a pedestal placed near the entrance, you could read a kind of statement by Walker, not so much explaining the exhibition as giving you a hint of what you were about to see. It said:

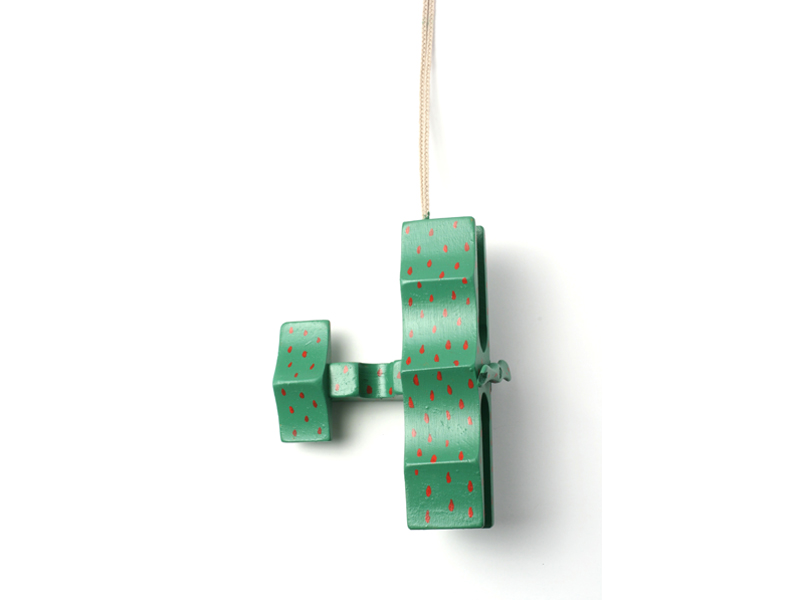

Picasso made a ceramic necklace for his wife Jacqueline. Claes Oldenburg made a stubbed-out cigarettes sculpture. Jurry Zielinkski made a face painting. I found a metal smiley face in a flea market in San Diego. Picasso made a face brooch. Iris Smeds made a necklace of words. Karl gave me a wooden airplane toy. An acquaintance 3D-printed a face copied from an online game. A musician friend gave me his oboe reeds and I made a necklace. / Lisa Walker, December 2015

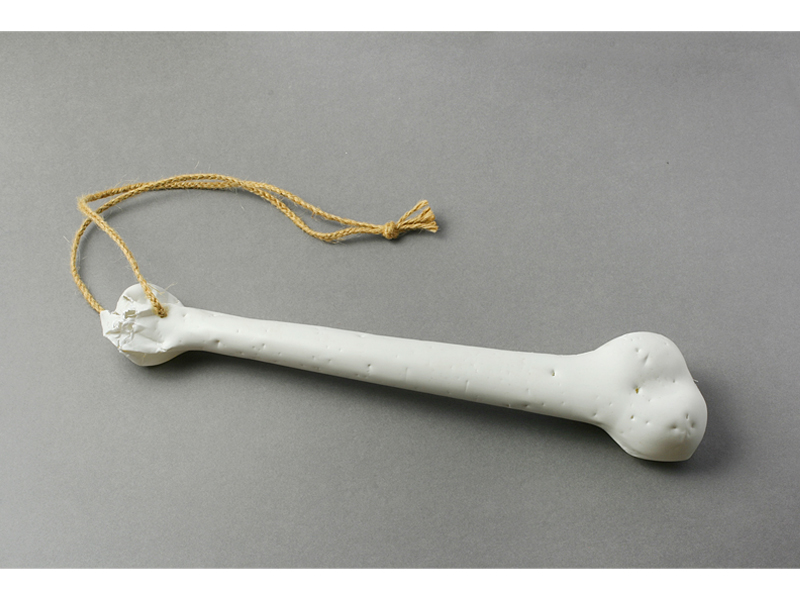

Through this short and poetic text, Walker gives away a lot of what this show could be about: art history, jewelry, gifts, and personal experiences. Looking up, I immediately notice works that are referenced in the text—a wooden airplane, a metal face, soft stubbed-out cigarette butts, a 3d-printed face, oboe reeds—all in the shape of necklaces. There are several more works here: a plastic bone, a set of plastic vampire teeth, what appears to be a kind of painted metal dish, wooden telephone receivers in green and red, and more—but mostly necklaces. Contemporary and seemingly primitive objects are placed side by side, some inside boxes, some on the wall, in a kind of surreal collage, juxtaposing personal stories with art history, private imagery with public symbols, in a way that kind of nullifies the tension between these concepts.

2.

A New Zealander with access to both a global visual and material language and to the local language and history of the Māori, Walker benefits from drawing on two different cultures as both a goldsmith and a conceptual jeweler. In one of the more emblematic pieces on show, she activates the New Zealand jade known as pounamu, considered by the Māori as a carrier of power or prestige for those who hold it.

The green stone, usually shaped by skilled hands into ornaments such as hei tiki or hei matau, consists in this case in cut-offs and leftovers. As I understand it, Walker did not shape the stones herself, but utilized an existing eight or so off-cut stones—triangles, circles, and squares—to form a new composition. In doing so, the artist picks up a conversation thread she has been busy with since studying in Munich: the concepts of skills and craftsmanship, or more specifically, the highly political notion of deskilling.

Let us propose a few hypotheses about what the implications of this cut-and-paste operation might be. With her background as a goldsmith, we can imagine that Walker could easily engage with the values and aesthetics of “doing something well.” However, deskilling and the use of readymades shift the value of the work away from craftsmanship—even though that is important as well—toward an artistic sensibility. A first hypothesis is that this work—like a lot of Walker’s work—constitutes a statement about what it is to be a contemporary jeweler: someone whose work is rooted in craftsmanship, but not beholden to its traditional standards.

In the case of the pounamu work, Walker also touches upon questions of cultural ownership and use, and another possible subject of the work is the dissonance between the Māori culture and the non-Māori culture. The jade has a significant meaning to the Māori people; it is considered a taonga (treasure) and as such, is protected under the Treaty of Waitangi, a treaty signed in 1840 between the British Governor of New Zealand and part of the Māori people. The treaty states which properties are recognized as owned by the Māori. The Māori definition of property, however, is broader than the English concept of legal property, and since the 1980s courts have found that the term can also include intangible things such as language and culture. This decision is part of what is called the Māori renaissance: a wider effort to reverse 150 years of cultural inequality, which in turn has given rise to a form of cultural protectionism of the Māori cultural heritage.

So when a non-Māori New Zealander turns out a large pendant from bits of pounamu, she is challenging several things at once. She is leveraging the act of ready-making (you take something somebody else has made and make it your own) against the capitalist concept of ownership. She is questioning the idea of cultural ownership, by both appropriating pounamou, and bringing to its transformation the kind of punk sensibility and DIY ethos we already associate with her work. This sensibility is in sharp contrast with the aura that surrounds Māori greenstone, or the respect that governs its transformation. This constitutes a provocative statement of self-empowerment: I take this which is yours, I place it outside of the value system (craft and culture) that gives you power.

3.

While the pounamu piece digs into political questions concerning cultural ownership, the wooden toy airplane neckpiece pinned two feet to its right seems to hang in the air like it just don’t care.

Or does it?

Picasso gave a jewelry piece to his wife. Karl Fritsch gave a toy to Lisa Walker. Lisa Walker then wrote an artist statement which points to many different forms of giving, and the fact that she tends to be on the receiving end: She receives, gets given, but also picks up, hoards, and, one assumes, swaps things. They then end up on the wall of a Munich gallery.

In anthropology, a gift economy—a system based on reciprocal gift-giving—is usually considered as opposed to the market economy of capitalist societies, but no less informed by power relations. Gifts establish invisible webs of emotional and social IOUs between persons and groups of people. The process and implications of gift-giving is dependent on the political, social, and economic system in which it happens. Still, one definition of a gift could be a form of transfer of property rights over particular objects.

So, again, the artist tackles ownership and, again, she posits her practice somewhere to the left of it.

In monetized societies, we don’t need anyone, we feel independent of others, we pay for what we want or need, but money could go to anyone—the capitalist exchange system is impersonal and therefore lacks the qualities of a community. In cultures built on gift economies, people are dependent on each other to pass on their surplus, rather than accumulating it. It is a collective way of thinking—to share the wealth and believe in the idea that the more people who have what they need, the better for the overall community.

If you consider an exhibition a gift—as I do—from an artist to the public, you could say that Walker has regifted the airplane toy. The piece—and the exhibition as a whole—suggests an alternative system of economy: one that borrows, receives, reinterprets, passes on.

This narrative is coherent with Lisa Walker’s practice to date (including her quirky habit of producing stage jewelry for Chicks on Speed, objects which seem to live—for now—outside of the market for Walker’s work), and would explain her enduring success as jewelry’s enfant terrible. It also begs the question of whether the subversive element of her positioning can survive so much institutional and collectors’ interest.

This is an old question (in the art world) but it is seldom posed in the jewelry world, so let me try to unpack it for you: Work made from bits of salvaged plastic is repurposed into loud and apparently facile provocations. This work more or less spits in the eye of “proper craft.” (How many times must she have heard “my three-year-old could have done this”?) It challenges economic and cultural systems of ownership and, by implication, the very gallery structure in which it is embedded. (Of course the pieces are for sale—some are accessible, others much less so—so it still belongs to the system where objects are exchanged for money.)

Meanwhile, Walker offers visitors a free experience which she in turn has worked long hours to produce. This of course could be said about most exhibitions, but as “giving” is one of the subjects in this exhibition—and the fact that jewelry very often takes on the role of a gift—it is interesting to see that the gift economy seems to be reentering modern capitalism, as a way of opposing the power structures of corporations over consumers, for instance in online communities and systems like open-source coding. And I do find a parallel between how Walker works as an artist, and how open source operates—anyone can pick up some lines of code to develop it further and, from an economic point of view, open source systems are owned by the community, open to all, as long as one has the programming skills necessary to write useful code.

The objects Walker takes are already coded with social, economic, symbolic, personal, and material meanings that can be drawn upon, developed or deconstructed and reconstructed, and added value to. This act involves the transformation of an object from a collective object into a singular object which, although it draws on the meanings already implied by the object, offers a particular interpretation and thus alteration of those meanings.

For this parallel to be plausible, we need to decide if the work hanging on Biro’s walls are also empowering for the visitors—whether they, in fact, can “develop it further” or, in viewership terms, get enough out of them to not feel conned by a game of faux subversion: Does she manage to weave together the mechanical consumer culture of postmodernity and the punk resistance of that culture into a kind of new symbolic and social fabric—fueled by the concept of the readymade-cum-gift?

The answer to that would have to be on a case-by-case basis.

4.

One of Walker’s great qualities as an artist is that she has a recognizable method for working which is simple and understandable, while at the same time the output of that method is extremely diverse and rich. Rich in references, emotions, layers of meanings, and challenging both on an intellectual and emotional level, some of the pieces deliver much more than the simple tease of being “something with a thread on it”: the pounamou piece is one good such example, as is, surprisingly, the airplane. However there are also some pieces in the show that seem almost not to belong in the context, that don’t have the same sense of magic that the major pieces have. The necklace with a cut-up face and hands in what appears to be Styrofoam sprayed silver and red is one such piece, the fur bracelet is another, the necklace with Playmobil body parts (mostly arms) is yet another. These works seem a bit unfulfilled, and the earrings in the show just feel out of tune with the overall exhibition—put in there primarily for sale maybe—although some of them do refer to other pieces and motifs in the show.

The stronger works are embedded with humor, art-historical references, personal stories, sometimes they play on the concept of primitivism, and sometimes they engage with new technology. Thanks to them, the exhibition as a whole conveys a feeling of generosity and warmth that ties the pieces together. Through all these emotions, her jewelry seduces me and seems to point to a possible way out of the cold hands of corporate capitalism that threaten to short-circuit modernity, without succumbing to its opposite; that exit route finds its origin in the powerful concept of giving and in a kind of usership that disregards ownership.