- This bilingual catalog supported an exhibition of the same name

- Both the show and the book aimed to promote the role and history of women in Austria in the field of jewelry design and in Austrian jewelry history

- The book is not successful on a number of levels

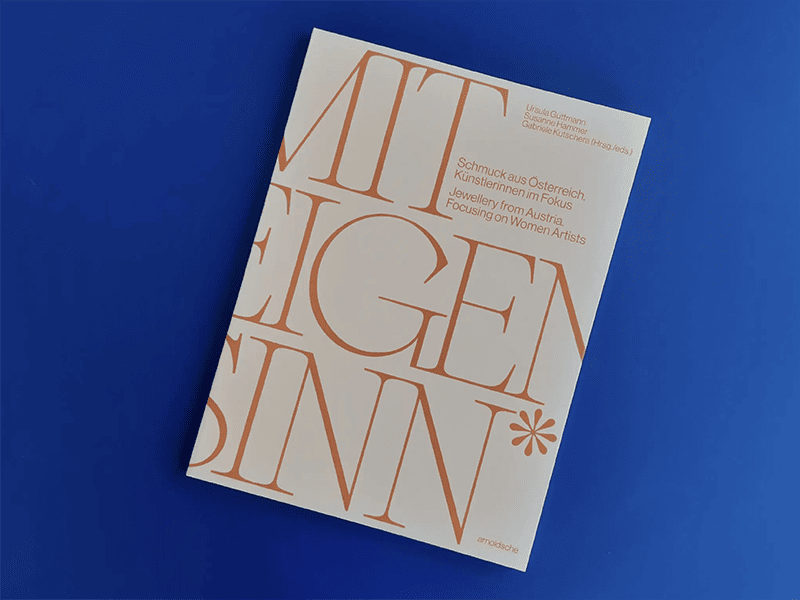

Ursula Guttmann, Susanne Hammer, and Gabriele Kutschera, Mit Eigensinn*: Schmuck aus Österreich, Künstlerinnen im Fokus/A Mind of Their Own, Jewellery from Austria, Focusing on Women Artists. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2022.

At first glance: the catalog design

The floppy salmon-colored cover features the title and authors’ names in orange letters. It looks pretty outdated. The layout of the texts is reminiscent of the 1970s and 1980s. Text pages consist of two columns. The one on the left contains the German text. The right one has the English version. The text lines of the different languages are not at the same height. The German text is in a compact font (Times New Roman Condensed). The English column is in a larger sans serif font (Neue Haas Grotesk). Sometimes a third font is used in titles or subheadings (Sometimes Times). It’s a visual hodgepodge, this graphic design by Studio Kehrer—unattractive in many ways.

Visual chaos

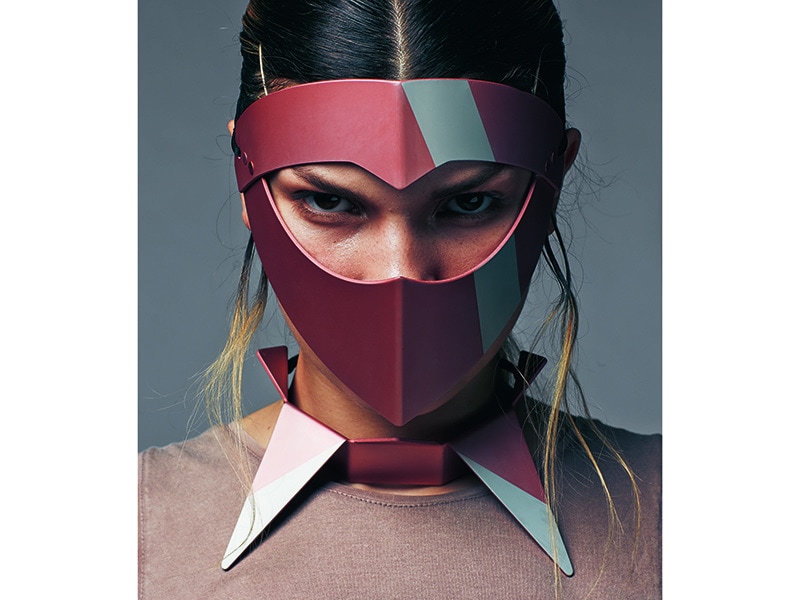

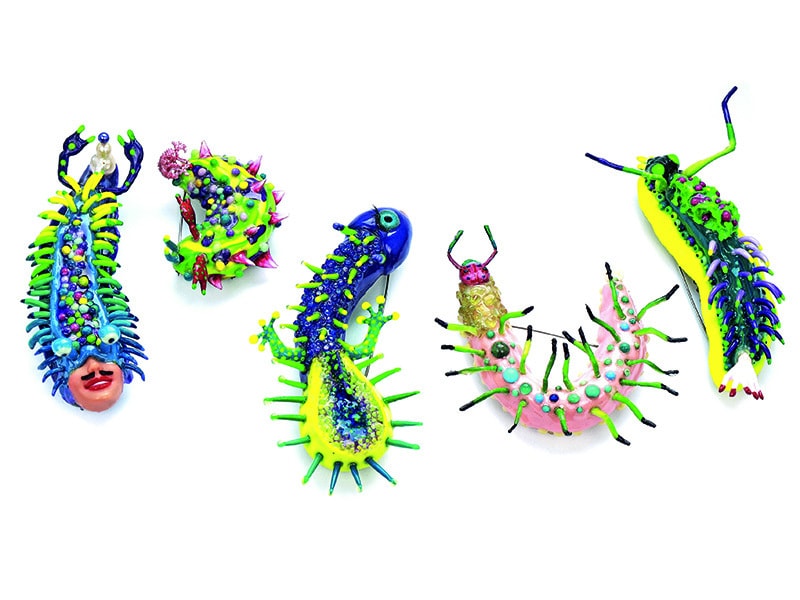

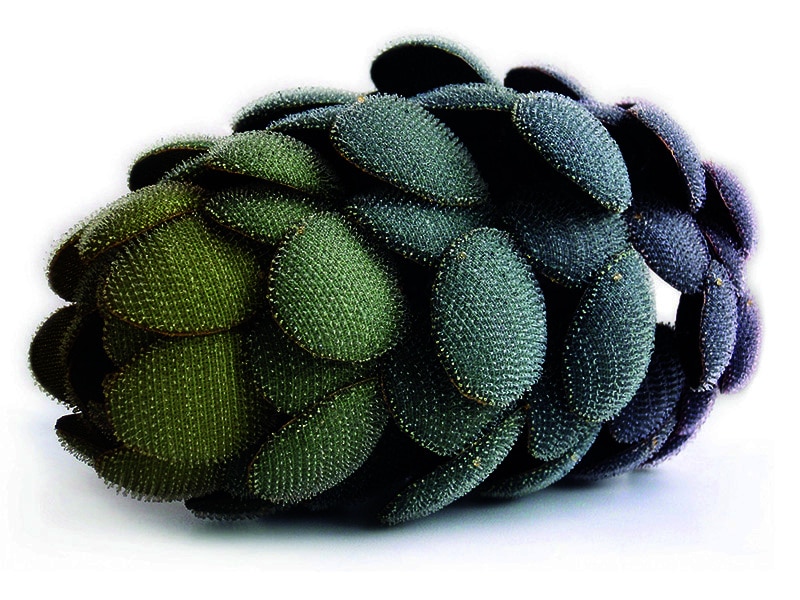

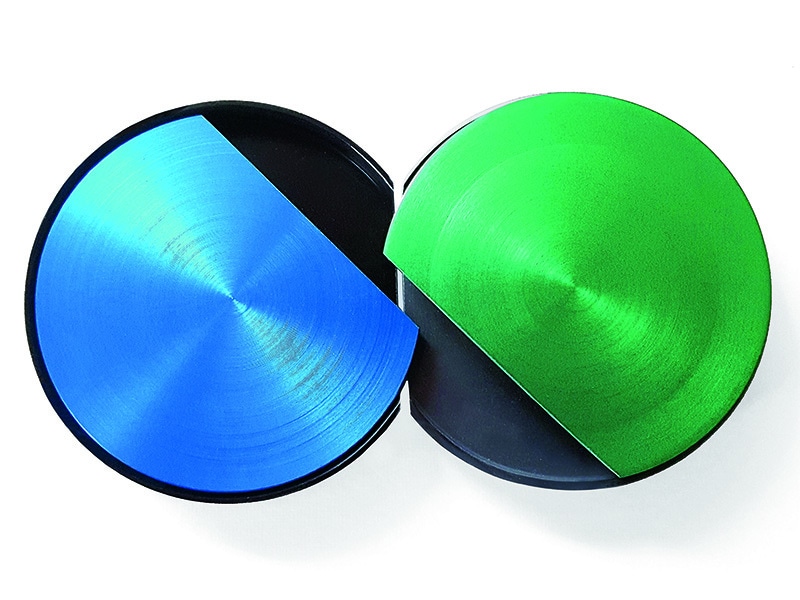

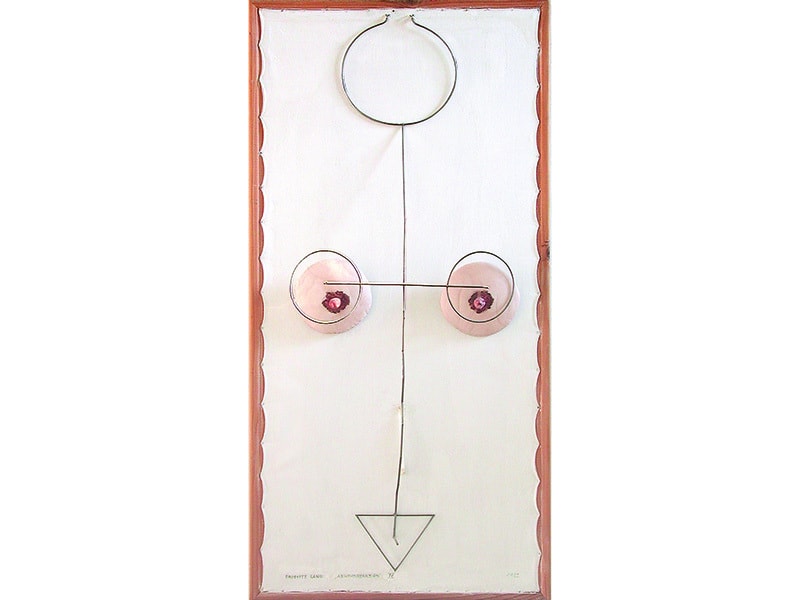

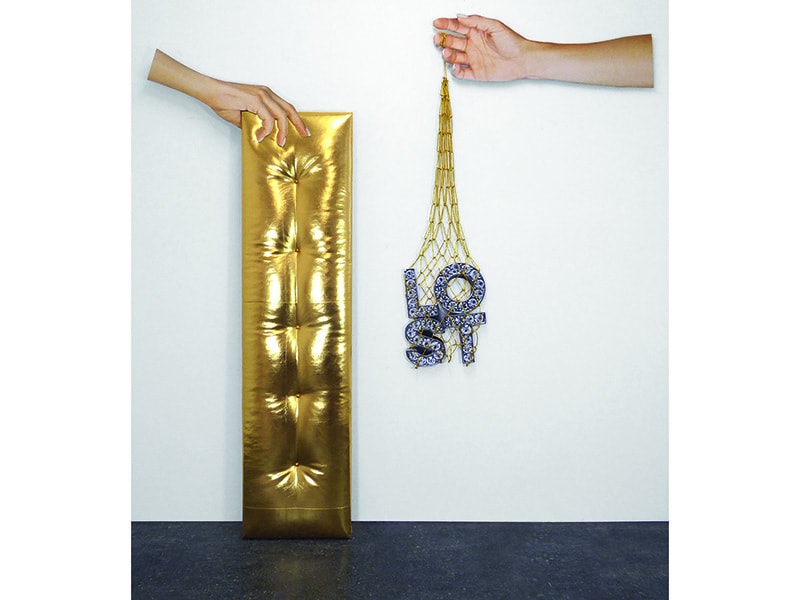

The photography of the jewelry in the publication is a mess. Each artist brought in her or his own photographers. This results in a total lack of visual unity or cohesion. This is remarkable for a publication from Arnoldsche: most of the books I know from this publisher are truly well-balanced gems. What happened here? Too many people involved? Was there no plan? Hidden agendas?

The exhibition

The exhibition[1] and catalog aim to provide an overview of what has happened in Austria in the field of contemporary jewelry since the 1970s. The show took place at a private museum, the Museum Angerlehner, in Thalheim bei Wels, Austria, in two rooms devoted primarily to exhibiting graphics and photography. As stated in the book: the owner of the museum, Heinz J. Angerlehner, was closely involved. The title of the project refers to a 1985 exhibition at the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (renamed Belvedere 21), in Vienna: Kunst mit Eigen-Sinn, Aktuelle Kunst von Frauen. But the motivation to refer to this title is not explained. It would be interesting to learn more about the connection between the two exhibitions.

Quirky?

Fifty-three artists were represented in the exhibition as well as in the book, both women and men. Aside from jewelry, objects, installations, and videos were on show as well. Quirky? I don’t see it. In the foreword, Gabriele Kutschera states that female artists have their own brains. What a commonplace idea. Or not? What a female brain looks like or how it differs from that of other people is not revealed. This is the story of the project: statements don’t get fleshed out.

First essay

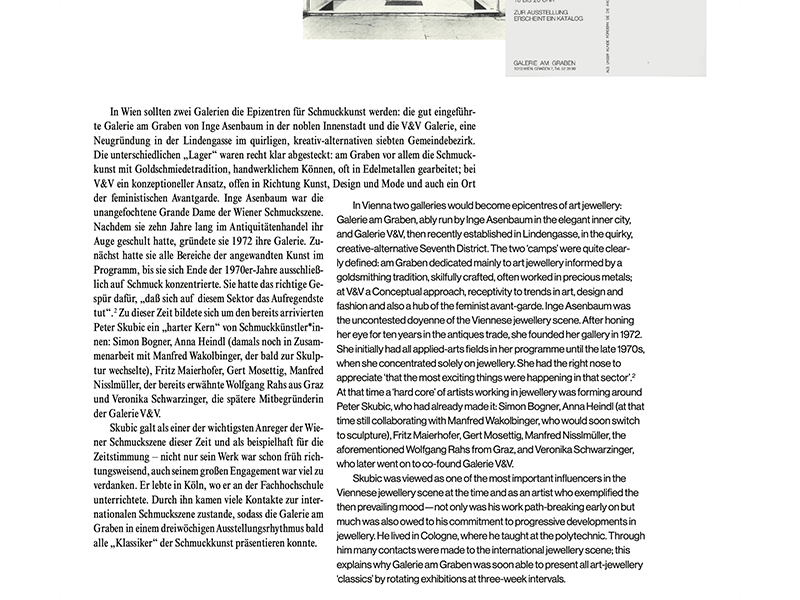

Désirée Schellerer, who works in the press department at the Belvedere, wrote the first essay. In the 80s she studied in Vienna and worked as a journalist. She shows photographs of the facade of the Viennese contemporary jewelry gallery Galerie am Graben and of the interior of the Werkstadt Graz artists’ studio. I love this kind of historical material and can often look at it for minutes at a time, but unfortunately these photos are printed too small for that. The dynamic art climate in Vienna and Graz is described, as well as the art schools in Austria that were in vogue. In Vienna it was the Akademie der Bildenden Künste and the Hochschule für Angewandte Kunst. However, the focus in these institutions was not on applied art. Not at all. They had no training program in the field of jewelry design. So why include them?

Nie wieder Gold! (No more gold!)

Among jewelry designers in Austria in the 1990s—just like in the Netherlands and elsewhere—it was just about taboo to work with gold. Jewelry was made from all kinds of materials. Aluminum, for example, was a popular medium. That did not mean that the jewelry was low priced and therefore available to everyone. Due to the labor-intensive manufacturing process, jewelry remained an elitist luxury product, just like elsewhere.

Jewelry designers in Austria sought recognition of their craft as an art form, but failed in this. Jewelry, however artistic, was still seen as applied art and not as an autonomous art form. Same situation elsewhere, nothing special for the Austrian jewelry community.

The Munich connection

Petra Hölscher (b. 1962), senior curator at Die Neue Sammlung, wrote the longest essay in the book. In it, she elaborates on the history of Austrian jewelry designers compared to the jewelry climate in Munich, Germany. It takes only three hours to drive between Munich and Vienna. Austrian jewelers were widely presented in West Germany at fairs and museums as early as the 1960s, especially in Munich. Hölscher describes how the work of Austrian jewelry designers was received in Germany. Fritz Falk, the director of the Schmuckmuseum (in Pforzheim, in West Germany), did not consider Austrian jewelry designers as innovators, but as followers of the avant-garde in West Germany.

Hölscher also discusses how education in jewelry design came to an end in Vienna in the mid-1970s. Due to a tragic turn of events, the momentum for contemporary jewelry in Austria was suddenly gone. When Wilhelm Mrazek, the director of Vienna’s Museum für Angewandte Kunst (MAK), left in 1978, the museum no longer paid attention to the young collection of contemporary jewelry that had been set up at his initiative. Art schools changed course and there, too, the departments where jewelry designers received training lost focus. Initially West Germany held plenty of interest for Austrian jewelers, but that attention faded away.

Left out

Viennese galleries such as Inge Asenbaum’s Galerie am Graben and V&V, set up by Veronika Schwarzinger and Verena Formanek, are regularly featured in the book. But there’s not a single word about Galerie Slavik. That’s weird. Austrian jewelry collectors, such as Heidi and Karl Bollmann, have also been left out. That’s strange, too. The couple actively collected and generously supported jewelry artists with, for example, the project Schmuck zur Jahrtausendwende. Breaking down boundaries between the traditional art disciplines is a noble goal, which I wholeheartedly support. Writing women into history is also one of my personal aims. It doesn’t work, though, when major factors are excluded. What happened here? How come Slavik and the Bollmanns don’t even get a footnote?

And why not mention the wonderful Viennese shopfronts and interiors designed by the Austrian architect Hans Hollein (1934–2014) for the jewelry company Schullin? When discussing jewelry in Austria, this cannot be neglected, unless some kind of gatekeeping is involved. What happened?

Limited

The aim of putting Austrian jewelry designers back on the map is admirable. Attention to women and other groups that have been underexposed in history is close to my heart. Unfortunately, this book provides only a very limited contribution to a previously scarcely described history. The exhibition and the publication together form an important and necessary attempt to draw more attention to the work of female Austrian jewelry designers. The effort in the publication was less successful. It doesn’t just look messy, it is messy. Who will come up with a better book?

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Mit Eigensinn*: Schmuck aus Österreich, Künstlerinnen im Fokus/A Mind of Their Own: Jewellery from Austria, Focusing on Women Artists, April 3–September 25, 2022, Museum Angerlehner, Thalheim bei Wels, Austria.

Reply to Esther Doornbusch’s book review

January 15, 2024

We thank Esther Doornbusch for reviewing the publication Mit Eigensinn* (A Mind of Their Own. Jewellery from Austria. Focusing on Women Artists) for Art Jewelry Forum, which we—initiator Gabriele Kutschera, Ursula Guttmann, and Susanne Hammer—as its editors and as co-curators of the exhibition of the same title read with growing astonishment and mounting disbelief. It is not just the wording of the text, which in fact barely meets the requirements of a well-grounded review. The review contains numerous erroneous interpretations and inaccuracies; accordingly, we see ourselves forced to undertake a much-needed correction. Since we would actually have to go into each paragraph individually but doing so would be beyond the scope of this reply, we will focus on the important paragraph on the exhibition as our example.

Esther Doornbusch writes,“The exhibition and catalog aim to provide an overview of what has happened in Austria in the field of contemporary jewelry since the 1970s. The show took place at a private museum, the Museum Angerlehner, in Thalheim bei Wels, Austria, in two rooms devoted primarily to exhibiting graphics and photography. As stated in the book: the owner of the museum, Heinz J. Angerlehner, was closely involved. The title of the project refers to a 1985 exhibition at the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (renamed Belvedere 21), in Vienna:Kunst mit Eigen-Sinn, Aktuelle Kunst von Frauen (Art with a Mind of its Own. Art by Women Now). But the motivation to refer to this title is not explained. It would be interesting to learn more about the connection between the two exhibitions.”

Both in the introduction (“MIT EIGENSINN*”) and in Gabriele Kutschera’s foreword (“Why Minds of Our Own*?”) the underlying motives and the context are described from various angles:

The meaning of “Eigensinn” as one’s own meaning—that is, one’s own significance in the sociological sense and in relation to Eigen-Sinn, the title of the 1985 exhibition (in the sense of appropriation, autonomy, self-empowerment)—is interpreted by Gabriele Kutschera with reference to artistic activity and the self-determination inherent in it.

In their text, the curators (Ursula Guttmann/Susanne Hammer) examine in depth the quotation described in this introduction from the context of the 1985 exhibition—“Willful as a form of appropriating the right to represent and express oneself, the experiences in one’s own environment, one’s own history”—which not only was crucial with regard to the 1985 show but is also relevant to our focus. The motivations and approaches to work shown by early women artists in jewelry (which are often in stark contrast to masculine conceptions) are elucidated with reference to individual positions. In both instances the texts highlight power structures, the question of autonomy and authenticity, of the authority to define (art) history, and, ultimately, the self-empowerment of women artists.

The reason for establishing a link between the two exhibitions, has, therefore, been more than sufficiently explained.

What is also incomprehensible is the assertion that Herr Angerlehner was involved in the concept planning. In his brief preface, it unequivocally states that he supported this exhibition project in his capacity as owner of the museum, but not that his involvement went beyond that.

Finally, we would like to stress that it was never the plan to produce a complete historical reappraisal, nor was this expressed, but rather to focus sharply on the pioneering women in the context of the early years of avant-garde jewelry, to describe the contribution they have made to Austrian jewelry, and to show the diversity of their approaches. This is also intended to be deliberately underscored with visuals. That may not be to everyone’s taste but the accusation, which, after all, runs through Doornbusch’s entire review, that we have acted without any plan is disrespectful, beside the point, and simply incorrect.

We would like to take this opportunity to once again expressly thank Dirk Allgaier and his publishing house, Arnoldsche Art Publishers. We were encouraged through conversations underpinned by his knowledge to engage in this subject.

—Gabriele Kutschera, Ursula Guttmann, Susanne Hammer