Several recent sales of modern and contemporary studio jewelry at prominent auction houses have set records for individual jewelers, signaling that the market for this work is growing.

In October 2021, Bonhams Los Angeles held its first auction devoted to studio jewelry, with 308 pieces from a cross-section of many of the most significant makers, such as Modernists Art Smith, Betty Cooke, and Margaret De Patta; Mexico’s William Spratling; Native Americans Charles Loloma and Jesse Monongya; as well as pieces designed by artists Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, and Jean Arp. Ninety-two percent of the work sold. Sales of pieces by Cooke, Spratling, Loloma, and Monongya set records. The sale, “Wearable Art: Jewels from the Crawford Collection,” was the first single-owner collection of such jewelry ever presented at auction, according to Bonhams.

Studio jewelry is usually fabricated by independent makers as one-of-a-kind work, or made in limited quantities, often with non-precious materials. Pieces by those known primarily as painters or sculptors, who frequently do not make them themselves, is called artist jewelry.

“There has been nothing on the market like this from an owner,” says Emily Waterfall, the director of jewels for Bonhams Los Angeles. Byron and Jill Crawford assembled the museum-quality works over a lifetime of collecting.

The top lot, a gold Grand Faune pendant by Picasso, sold for more than $62,000. The sale brought forth—and set records for—the work of several studio jewelers who are rarely presented at auctions. A new record was set for Loloma, a Hopi maker known for unusual combinations of stones, with his silver, gold, wood, and multi-stone cuff selling for $40,312. He had eight of the 10 top-selling items at the auction, with sales ranging from more than $40,000 for a gold and turquoise ring to several cuffs that each sold for more than $30,000.

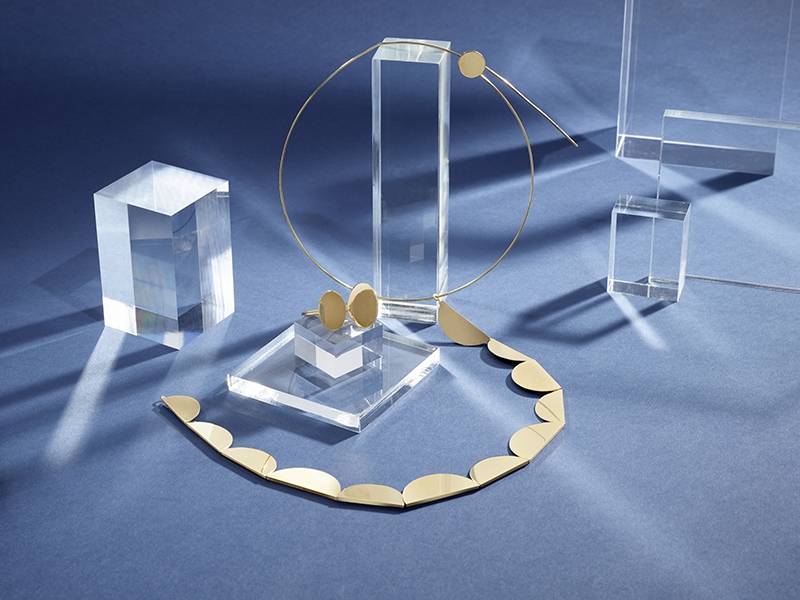

A gold convertible necklace by Cooke, designed as a wire collar with a line of half-moon disks of varying sizes, had a pre-sale estimate of $3,000–$5,000. It sold for $9,562, a record for the maker. “Betty Cooke’s work hadn’t been sold on the market in this quantity before,” Waterfall says. “There were more than 30 items, which was rare, and they sold well.”

Night Sky, a multi-stone cuff in gold by Monongya, a Navajo/Hopi jeweler whose pieces often feature designs of the galaxies in lapis, jade, malachite, and diamonds, set a record for the maker. The piece sold for $21,562, eclipsing a pre-sale estimate of $10,000–15,000.

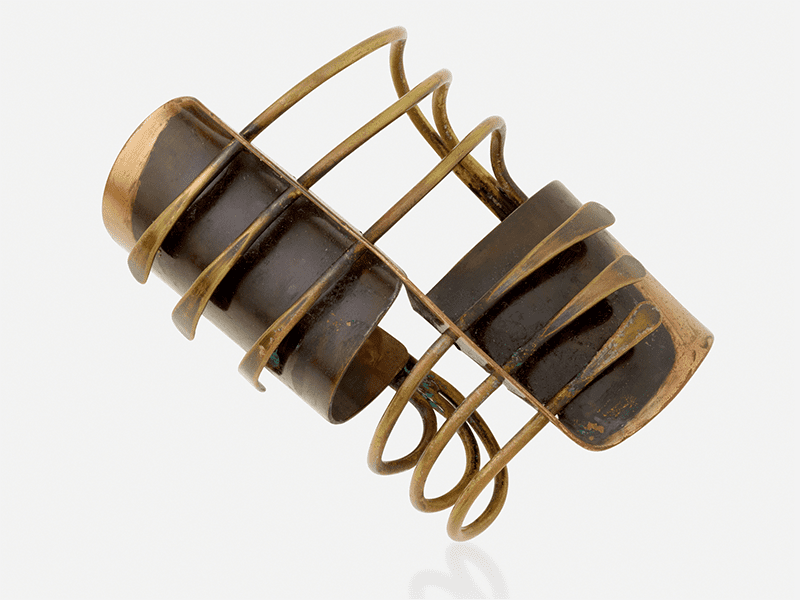

Dianne Batista, director of jewelry and watches for Rago/Wright/LAMA, believes that an important part of bringing this work to a larger audience is presenting it in auctions alongside fine jewelry. “We put studio art jewelry into our jewelry auctions to show the breadth of this field,” she says. “People wear jewelry of all types—the woman collecting a fine pair of diamond earrings most likely also has jewelry in her collection that is hand-worked by an artist. We all can wear and collect all types of jewelry. It doesn’t have to be in these narrow categories.” In October 2022, Rago will be offering Art Smith’s Diminishing Spirals necklace and other studio pieces. Smith was an African American who worked between roughly 1940 and 1970 whose avant-garde creations are highly coveted.

Another key element to presenting art jewelry at auction is including supporting material that educates people about the work. “It’s a rather young field in the world of art collecting, and people just don’t have the knowledge,” Batista says. “Education is key, as people are collecting more in this category and wearing it more.”

Auction houses are including biographies of the artists and makers, as well as period photographs of the pieces, such as advertisements they appeared in when they first came to market. “People are looking for one-of-a-kind pieces, and also the story behind them,” Waterfall says. “We are the storytellers of this, so it’s important how we tell the story.”

Smith’s Modern brass and copper cuff bracelet was presented online by Rago with photos from the late 1940s of Smith holding the bracelet as well as a model wearing it, alongside a Smith biography. “Sometimes we bring this research to the public for the first time,” Batista says. “Buyers can imagine for themselves who wore it, its history. We have clients who have said, ‘I never knew that artist, but her life resonated with me, and I had to buy it.’”

Work by women and people of color has been especially in demand, and many of those makers have fascinating personal stories, Waterfall points out. “What’s drawing people is how extraordinary these artists are. It’s an important part of history.”

Batista agrees. “People of color had often been left out of the jewelry story, so there is well-deserved attention now being given to those artists. It’s important to bring them to light.”

Another record was set in the Bonhams auction for the work of American ex-pat William Spratling, the father of Mexico’s Taxco jewelry, which began in the 1940s in Taxco, Mexico, a place known for its silver mines. His silver and amethyst jaguar necklace and brooch, ca. 1930–1946, are composed of jaguar and arrows motifs accented by amethyst cabochons. The pair went for $15,300. “I was floored by the response to Mexican silver,” says Waterfall.

For the auction house, the sale’s results signaled that “we have opened up an important new area for Bonhams,” Waterfall says. “I feel strongly that art jewelry is starting to take a prominent spot in the luxury world. People are hungry for this work. They want to wear something other than a diamond, and this speaks to their taste.” Bonhams will hold its second sale of artist jewelry on November 10, 2022, in Los Angeles, and Waterfall hopes it will become an annual event.

A record was set for Claude Lalanne’s work at a Christie’s online sale in March 2022. Her Dahlia necklace, which had an estimate of $4,000 to $6,000, sold for $113,400, more than 18 times its high estimate. The sale set a new record for a necklace by the French sculptor.

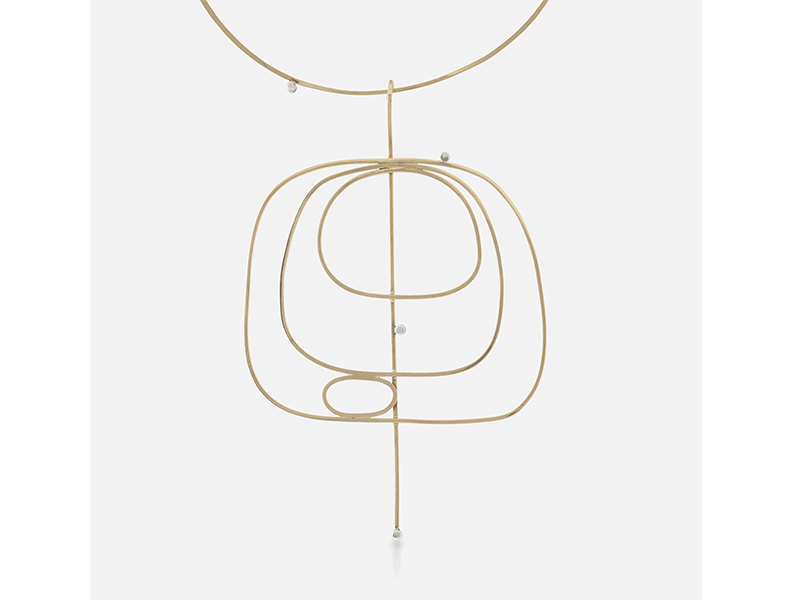

Sotheby’s held its first sale dedicated to artist jewelry in fall 2022, with more than 150 works in the online auction “Art as Jewelry as Art.” It showcased the work of several dozen artists, including Alexander Calder, Salvador Dalí, Ernst, Picasso, and Harry Bertoia. The sale presented the pieces “as a defined category of art for a collection that is not only intended for adornment but also as a means of personal expression,” says Tiffany Dubin, who was head of the sale for Sotheby’s. A Lalanne belt of galvanized copper and bronze with a $15,000 to $20,000 estimate sold for $44,100. Two 23-karat gold pendants by Ernst sold for more than $47,000 each, on estimates of $20,000 to $30,000.

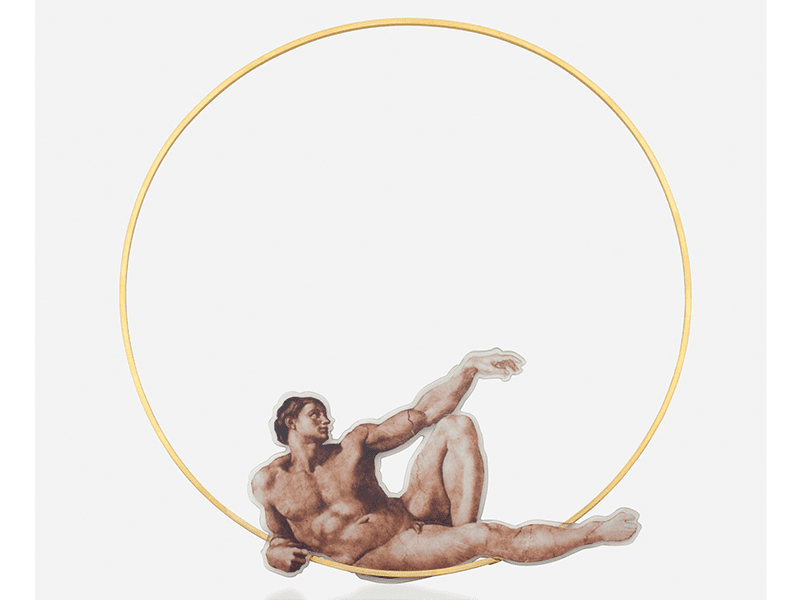

The “Summer Jewels” sale at Rago Auctions in June 2022 featured pieces from leading figures in the world of contemporary art jewelry and studio jewelry. An iconic Smith brass and copper Modern Cuff, ca. 1950, which had an estimate of $6,000 to $8,000, sold for $22,500. The sale is believed to be the record for this bracelet, and just shy of the $23,400 paid for Smith’s undulating brass collar necklace at a 2021 Rago/Wright/LAMA auction. Other top sales in the 2022 summer sale included a Gijs Bakker necklace depicting Adam from the Sistine Chapel, which went for $8,125. A Cooke gold pendant necklace with silver accents garnered $5,125.

At Rago/Wright’s 2020 auction “Structure and Ornament: Studio Jewelry 1900 to the Present,” curated by Mark McDonald, pieces by Bruno Martinazzi and Arnaldo Pomodoro far exceeded their estimates. A Pomodoro yellow and white gold bracelet, with an estimate of $15,000 to $20,000, sold for $43,750. And Martinazzi’s iconic Goldfinger bracelet, from an edition of 12, sold for $37,500, well above the $15,000 to $20,000 estimate.

A silver lining of the pandemic is that buyers are increasingly comfortable with bidding from afar on a computer or a smartphone. That has expanded the audience that auction houses can reach, with more buyers from all over the world tuning in for sales. There has been significant interest in these auctions from buyers in the United States, Europe, and Asia, as well as other locations worldwide.

For so many reasons, more and more buyers are attracted to this work, Waterfall says: “People are not wearing the big jewels as much as they used to. They like the idea of jewelry that’s interesting. It’s fun to express yourself this way.”