Contemporary jewelry has many foundations, awards, and grants, all of them a bit different. The Françoise van den Bosch Foundation,[1] named after a Dutch artist who died young, has been a well-established institution for over 40 years. How did it achieve this, when others have vanished in the mists of time?

A sketch of the foundation

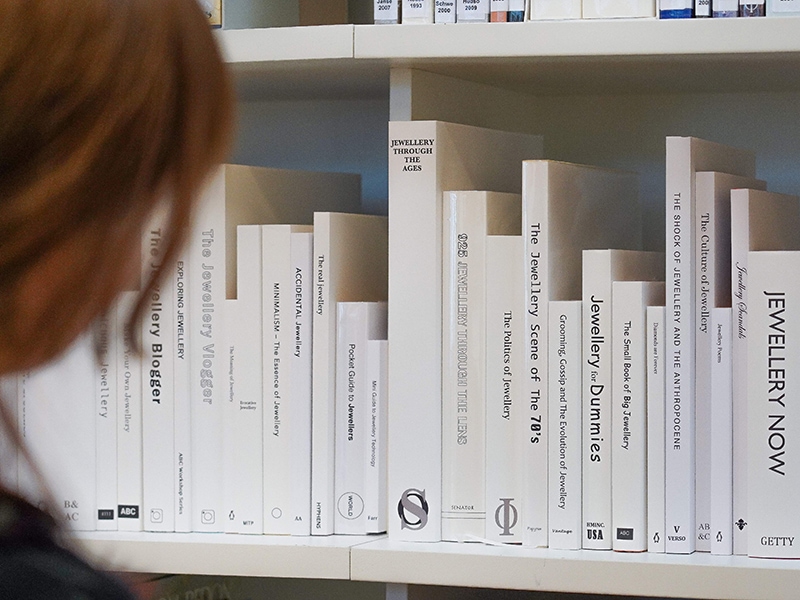

“To stimulate and promote contemporary jewelry.” Although its activities have expanded, this has been the foundation’s unaltered aim since its start in 1980. Today the foundation’s main undertakings are an award, a collection, and a residency, plus one-off activities such as talks, essay commissions, and collection presentations.

When Françoise van den Bosch[2] (1944–1977) died, she left behind her own work and pieces that she had swapped with contemporaries such as Gijs Bakker and Ruudt Peters. From this core, the foundation’s collection has grown every year—either with work acquired from award winners, donations, mid-career acquisitions, and young talent acquisitions. The latter applies to artists under the age of 33—Françoise’s age at death. With 400 pieces, the foundation’s collection is not the Danner Stiftung, but it is not small, either. Housed in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, its preservation is in good hands but there is no guarantee of display.[3]

Since 2011, jewelry artist Rian de Jong has facilitated an artist-in-residence program in her Amsterdam studio-apartment.[4] Among past guests: Moniek Schrijer, Florian Weichsberger, Mallory Weston and, this year, Triin Kukk. Probably coincidentally, US artists are overrepresented.

But most likely you know the foundation for its biennial Françoise van den Bosch Award. This prize has been awarded to an impressive list of jewelry makers including Marion Herbst, Otto Künzli, Onno Boekhoudt, Esther Knobel, Bernhard Schobinger, Lisa Walker, and most recently, Chequita Nahar.[5]

The Françoise van den Bosch Award

This award honors the entire career of an artist, not only their most recent work. Every other year, an independent jury of international experts—including the previous winner and one board member—deliberates behind closed doors. Only the outcome—that much anticipated name—is communicated. There is no open call, no shortlist, no exhibition of submissions, as for the Herbert Hofmann Preis and the show at Schmuck Munich.

The spirit of Françoise, ahead of the conventions of her time, is present in each recipient. The first laureate was Paul Derrez.

With the zeitgeist, the notion of what is innovative and bold changes. Just read the jury reports on the foundation’s website over the years: a plea for artists who put the jewel center stage, then a search for artists who think conceptually, later a focus on the connection to the body (not overly important for Françoise), or political dilemmas like winners from the Netherlands versus international winners.

The winner had always received a sum of €5,000. This year, two anonymous couples doubled it, to amplify the award’s impact. Every winner receives a “trophy,” a piece of jewelry made by a student. The collection acquires work by the recipient. To mark the occasion, some winners publish a book, others hold an exhibition in the Netherlands. Marc Monzó was featured in Design Museum Den Bosch and Sophie Hanagarth in CODA Museum Apeldoorn. David Bielander presented his work in a celebration with spectacular scenography in Museum Arnhem. Ted Noten organized a fashion show with his exhibition in the then Stedelijk Museum ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Twelve models wore his jewelry on the “Tedwalk.” Lin Cheung and Lauren Kalman were honored with a symposium, hosted by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Françoise’s serious play

What is the recipe for the foundation’s continued existence? The quick and vulgar answer would be: “sufficient means.” But let’s start at the beginning.

The foundation is named after a progressive Dutch goldsmith. Or artist, as she would prefer to be called. Françoise was active at the end of the 60s and 70s. She came from a noble family. Her inclination for sports was understood, but not her artistic ambitions. The expectations for a girl of her standing, combined with concerned but covert meddling over her epilepsy, burdened her. But she persisted.

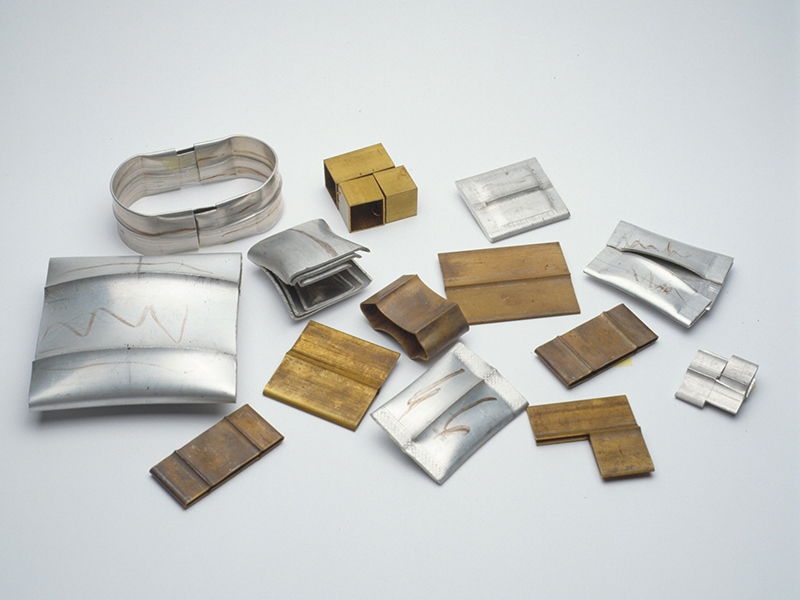

After art school, having left gold and silver behind, she worked with aluminum rod and other industrial materials. She cut and plied slices of standard-dimension tube, lovingly polishing the resulting cushion shapes to a soft feel. She called the endless experiments with nonprecious metals “playing.” The studio was full of aluminum samples with black scribbles. These were the charred marks of testing the temperature of the aluminum, which does not change to cherry red like silver. They look like notes to remind the serious artist to do better here or rework something there.

Many of Françoise’s pieces consisted of two parts that slid in and out of each other. Her design for an interlocking black and white aluminum bracelet serves as the logo of the foundation. A sculptor acquaintance of hers has suggested that Françoise missed having intense and long relationships in her life. We can’t ask her. But at the time several jewelry artists designed two-part jewelry. Think of Hans Appenzeller or Paul Derrez, whose two-component Wisselring from 1975 became a classic.

Innovating the notion of jewelry

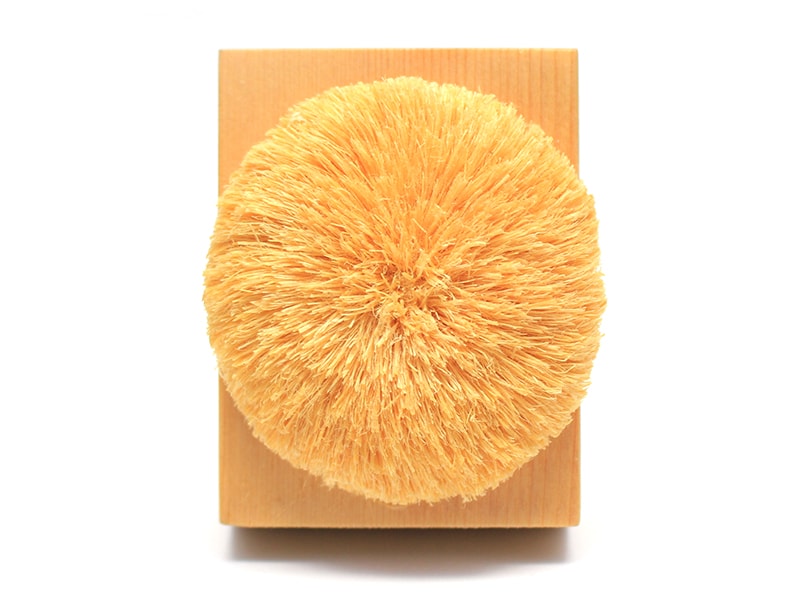

In 1969, at only 25, Françoise participated in an international exhibition with the slightly older Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum. Called Objects to Wear, it presented their mission for jewelry: a focus on the design and not on gold and gems. It was the era of working in series or multiples. Françoise wanted to make her jewelry less expensive and widely available. Later she joined a group of avant-garde artists in Amsterdam, the B.O.E.-group. This “Union of Rebellious Goldsmiths” sought appreciation for their work for its artistic value. They showed their work in galleries instead of selling it from the conventional jeweler’s shop. And they demanded a better income.

Chance encounter

One evening in 1969, the young museum curator Jerven Ober and his wife, Annelies van der Schatte Olivier, were strolling along Amsterdam’s canals when a new jewelry gallery drew their attention. Van der Schatte Olivier was mesmerized by a stainless-steel two-part bracelet. Françoise made her first sale, and the couple learned of the existence of this type of jewelry. During his career, Ober tried to present crafts as equal to art. He became an advocate for jewelry, most notably in what is now CODA Museum Apeldoorn.

The couple befriended Françoise. Van der Schatte Olivier remembers her as serious about her work and serious about her friendships. One day, she and the children stayed with Françoise, who was over the moon over a piece of equipment she had managed to buy off a metalworker in the neighborhood. It was just perfect for bending industrial tube.

A plan to honor Françoise’s memory

After Françoise’s sudden death in 1977, her family arranged a private funeral. Her friends from the art world felt they had not had a proper way of saying goodbye. Immediately an idea to honor Françoise’s memory formed. Eventually a delegation visited the Van den Bosch family. They presented the idea: a foundation in Françoise’s name to promote and stimulate contemporary jewelry. The Van den Bosches supported the plan with an endowment. Stedelijk Museum curator Liesbeth Crommelin, Jerven Ober, and Françoise’s brother-in-law Piet-Hein Verspyck Mijnssen signed the founding paperwork. Verspyck Mijnssen, who would become the longtime foundation treasurer, invested the initial sum wisely. This, plus yearly membership donations by faithful friends, has kept the foundation’s activities possible for more than four decades. Over time, the small group of the foundation’s “friends” has gradually been replaced by people from all over the world who never knew Françoise personally.

Commitment

How can an institution like this survive? Sufficient means are one component. But equally important: people, people who volunteer as loyal board members and willing jurors.

The 42-year-old foundation is now on only its third treasurer and its fourth chairperson. After Jerven Ober, Paul Derrez, and Liesbeth den Besten, the current chair is Martijn van Ooststroom. In the early days the board members were direct friends of Françoise. They would all squeeze in a car to have a board meeting—read: leisurely dinner—at Marion Herbst’s dike house, for instance.

In those days people seemed to have more time, and cars were smaller. But today still, knowledgeable people from the field expend their energy. All serve unpaid, and meetings are still held in board members’ homes to keep overhead costs low. Today board members are Dutch speakers but not always Dutch. They are based in or near the Netherlands for practical reasons. The latest additions are Jeannette Jansen, Morgane de Klerk, and treasurer Jeroen Redel.

Why all this dedication? The international renown that the foundation has gained is a factor. And let’s not rule out the James Dean effect: a highly gifted woman with a desire for an artistic life that did not fit her family’s background, combined with her untimely death, has its appeal. For me, it’s Françoise’s attitude, technically uncompromising, that led to designs ahead of her time.

The wish of the founders

In 1980 the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation got a running start with a substantial sum. The contributions of a group of loyal supporters, whether financial or in time and energy, have given it a long-term presence.

The desire of Françoise’s friends to honor their talented colleague and to “stimulate and promote” contemporary jewelry, has succeeded. Françoise van den Bosch’s name continues to be mentioned as a trailblazing figurehead for jewelry.

—-

Additional reading

Ober, J. (ed) (1990). Françoise van den Bosch (1944–1977). Naarden: Françoise van den Bosch Foundation

Acknowledgments

This article was based on an unpublished interview by Maja Houtman with Françoise’s contemporary Michiel Dhont (on March 9, 2016) and my conversations with Otto Count van den Bosch, Mrs. Thea Verspyck Mijnssen-van den Bosch, and Ms. Diana van den Bosch, brother, sister, and niece respectively of Françoise van den Bosch (September 21, 2020); Paul Derrez and Willem Hoogstede (April 9, 2021); Annelies van der Schatte Olivier (April 15, 2021, and March 4, 2022), accompanied by the rattling aluminum sound of an original black and white Françoise van den Bosch bracelet—van der Schatte Olivier’s favorite—around her wrist); a phone call with Lous Martin, cofounder of Galerie Sieraad, the aforementioned Amsterdam gallery (August 22, 2022); several conversations with Liesbeth den Besten, longtime chair of the foundation, with whom I had the pleasure to overlap on the board for a couple of years; and the valuable points of view of the current chair, Martijn van Ooststroom, about what makes the foundation unique.

[1] https://francoisevandenbosch.nl/.

[2] Pronunciation help for non-Dutch speakers: Bosch rhymes with “boss,” and not with “ohmygosh.”

[3] The collection can be found online and has been described here.

[4] The deadline to apply for the 2023 artist-in-residence program is this week: September 15, 2022. Learn more here.

[5] See all the recipients here.