Also in this series:

- Black Jewelers: A History Revealed—Rediscovery

- Black Jewelers: A History Revealed—Bill Smith

- And coming soon: Coreen Simpson

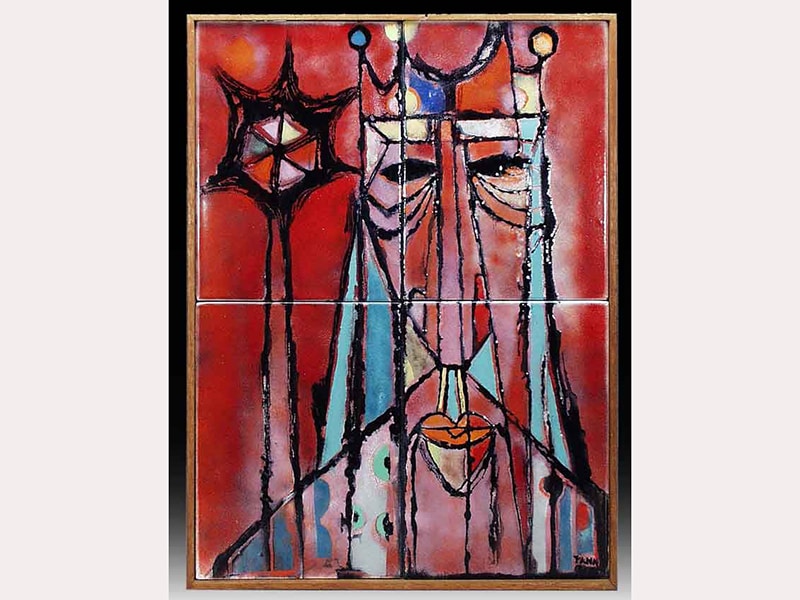

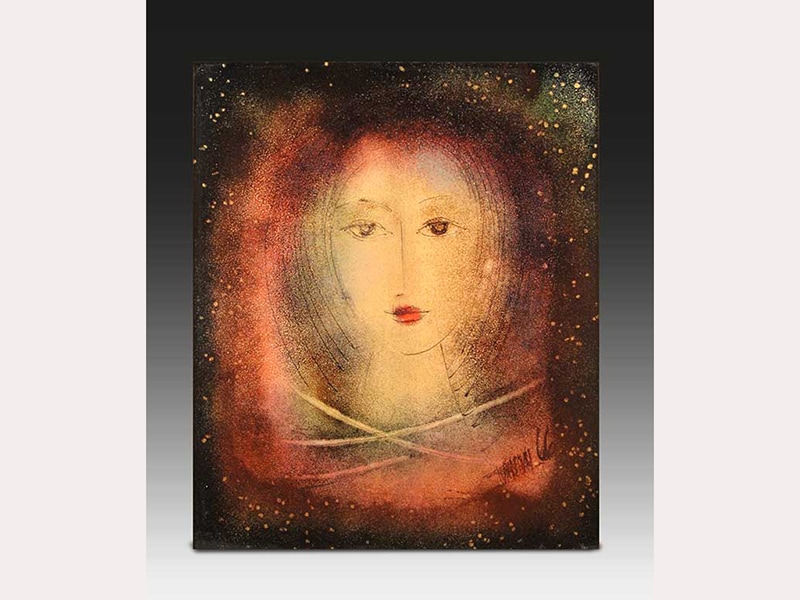

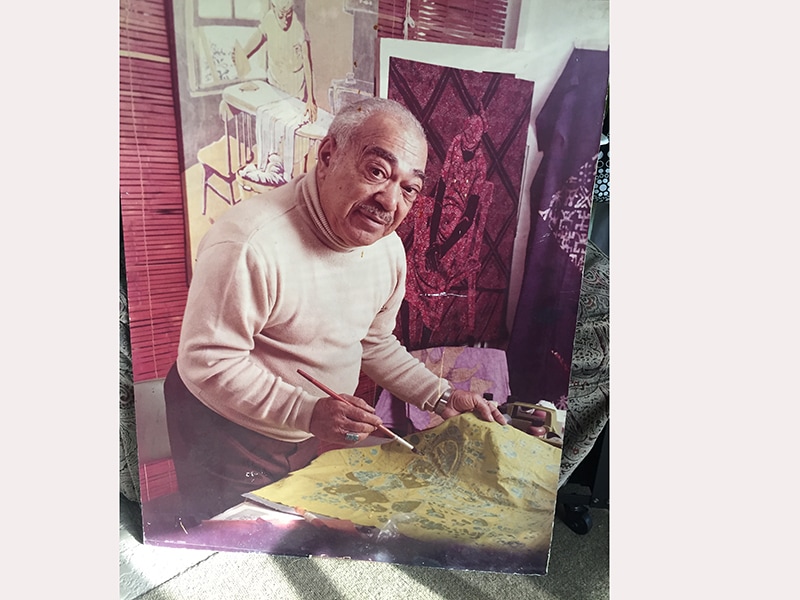

Earlier this week, we introduced this new series, which documents African American artists of the past who have made important contributions to the field of art jewelry.[1] The first profile spotlights Curtis Tann. This artist serves as an example of a great name and a prominent person in the world of jewelry whose efforts have yet to achieve the recognition he deserves. While Tann’s name hasn’t been prominent in the world of art and design, his contributions and his connections to some of the most important figures in contemporary art show the amount of influence he brings with his creative talents. From his whimsical work in enamel on copper to his early experiments with tie dye and batik, Tann’s career throughout the mid-20th century produced stellar design and creative triumph, especially in the field of jewelry.

Although we will mostly discuss Tann’s career in jewelry, he originally thought of himself as a fine artist. He created jewelry and design on the side only as a means to make ends meet. However, Tann’s most recognized contributions to the arts have mostly been his work in jewelry. It is this important output that we will cover in our discussion of his work.

Curtis Tann was born on December 4, 1915, in Circleville, OH. His father was employed as a laborer, while his mother was a day worker. The family lived in Cleveland by the time he started elementary school. They endured some hardship after his father was fired from his job for being a black man around the beginning of the Great Depression. Although he was not openly encouraged, Tann started learning creative arts from a young age, at first from his father. After his father discouraged Tann’s interest in making a serious pursuit of art, his talent was then secretly enhanced by his mother. “It takes nerve,” Tann’s mother would often say about pursuing a career as an artist. “You have to have nerve.”[2]

He eventually attended William H. Kirk Junior High School, in Cleveland. There, the young Tann gained more exposure to the arts. He learned printing and design and painting with watercolors. By the time he graduated, he had turned down a scholarship to attend Fisk University. Instead, he began teaching arts and crafts at Hiram House, a youth camp in Moreland Hills, OH. There, he prepared for the future role he would have in arts education. Through his connections at Hiram House, Tann was soon taking major steps in his career at Karamu House.

Karamu House was formerly known as the Playhouse Settlement. It is the oldest African American theater in the United States, in the Fairfax neighborhood of Cleveland. It was also one of the few prominent art schools in early 20th-century America that catered primarily to African Americans. The theater created a space for African Americans to be educated in the arts during a time when that privilege was often unavailable. During Tann’s time at the theater, he became a member of the Gilpin Players. They performed in original productions by Harlem Renaissance greats such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston.

During his time at Karamu House, Tann first encountered the techniques of enamel on copper. He studied the Limoges technique under Thomas Usher. Yet his progress was cut short when America’s involvement in World War II began. Upon entering the military in 1944, Tann traveled to Italy to help with liberation efforts. He saw the many treasures of the Italian Renaissance, which further inspired his artistic creativity. It appears that after the war, the Army promised him a chance to attend the Institute of Art at the University of Florence, but his commanders reneged on the deal at the last minute. After returning from the war, he decided to leave Cleveland to start his career in Los Angeles, carrying only $10 in his pocket.

According to his oral history, Tann forgot about his education in enamel after the war. For a while he worked doing necktie design, first working at Allen of California from 1946–1948, and then at Palm of California from 1948–1952. But in 1947, his mother sent him a box of old memorabilia. It included the first piece he had made, and he rediscovered his talent. This made him reconnect with Thomas Usher for a refresher course in 1949. He then decided to seriously pursue enamel arts as his life work.

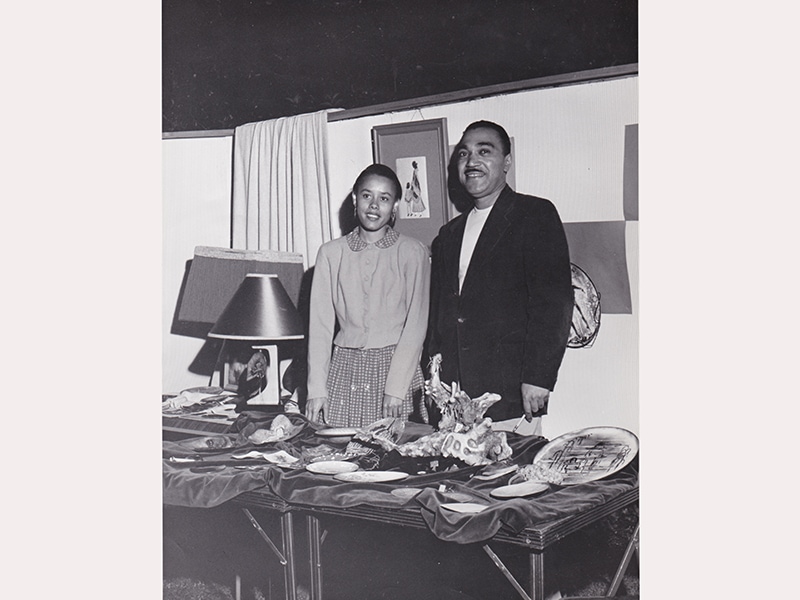

Tann eventually settled in Pasadena, CA. By the early 50s he was a part of the burgeoning artistic scene in the greater LA region. He mingled with legendary African American artists such as Charles White, Doyle Lane, and Dale B. Davis. In addition, he became a founding member of Eleven Artists Associated. It became one of the first organizations to help and support African American artists. (It was later called Arts West Association.) All these major feats started his practice on a high note. But he might be most influential via his role in introducing Betye Saar (née Brown) to the LA art scene, before she became a legendary artist.

Back then, the two teamed up to launch a company, using the tongue-in-cheek name Brown and Tann. They created different pieces, from ashtrays to bowls and enamel jewelry. These were sold at various art fairs at the Biltmore or Alexander Hotels. The company gained some early success, and Ebony magazine gave it a feature. However, it eventually dissolved after Saar discovered an interest in printmaking. She later moved into her current field of assemblage.

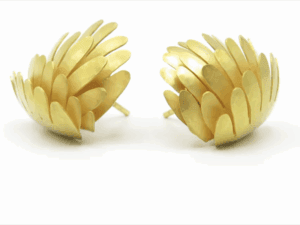

Meanwhile, Tann continued creating works in enamel on copper. He furthered his career in jewelry by becoming a designer and supervisor for costume jewelry company Matisse Ltd. (It was a subsidiary of Renoir of California. Both companies were founded by Jerry Fels, an important name in costume jewelry.) For Matisse, Tann focused specifically on enamel jewelry. He provided designs that capture his whimsical style and use of bright colors. The work depicted both abstract geometrical shapes and figurative images, including fish, paint palettes, or musical notes. Tann worked at Renoir-Matisse Ltd. from 1952–1963. He then worked for designer Sascha Brastoff for a year. There, he continued to provide designs for enamel.

Tann often mentions in his oral history his struggles working as a black man in a predominantly white field during his employment at Renoir-Matisse and Sascha Brastoff. According to Tann, he was treated poorly by the company due to racism, as was prevalent in the 1950s. He was paid a lump sum (which he most likely accepted in desperation to make ends meet for his family) for most of his designs for the company, and was not given any credit for the work which was mostly his. He often had to deal with the lack of recognition and the exploitation of his work by both businesses, as they continued using his work for years without crediting him or paying copyright. He created many designs for both companies. But the acknowledgment of his work and contributions in retrospectives of Renoir-Matisse was often left to the appendices, while greater and more popular members of the company received the credit. “My name was not used, but my work was,” Tann explained in his oral history. “I was exploited to the nth degree […] and I hope and pray that it doesn’t happen to any other black artists.”[3]

Despite the difficulties he experienced during an era of discrimination, Tann never expressed ill will against his former employers. Instead, he viewed his challenges as learning moments. He hoped these would create a new generation of more knowledgeable black artists. Tann wanted those makers to gain the success he failed to achieve.

Tann continued to pursue the important goal of spreading knowledge. He got more involved with education in the late stages of his career. This was one of his most important contributions to the world of Black art in California. In 1967, he became the first full-time director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, the first organization to bring arts education to the children of the South Central Los Angeles community, after the departure of co-founder Noah Purifoy. Tann also specialized as an arts educator, teaching classes in enameling, batik, tie dye, other arts, and various special-education programs. These classes were given at the Pasadena Art Workshops—where he was a recipient of a grant from the California Arts Council—the Pasadena Art Museum, and the Watts Towers Arts Center.

Curtis Tann died in 1991. He left a legacy dedicated to progressive action into spaces that were blocked to Black artists in the 50s and 60s, and committed to education and inspiration to other Black creatives. His enamel art missed the opportunity to gain the recognition it deserved during his lifetime, but it lives on through the successes of his friends, such as Betye Saar. It shows in the fight for acknowledgment in Eleven Artists Associated. You can see it in Watts Towers Arts Center, which still exists today. I hope that through the continued spreading of his story and his achievements, Tann will receive long- and well-deserved honor for his efforts.

[1] See https://artjewelryforum.org/articles/black-jewelers-a-history-revealed-rediscovery-article-black-jewelers-a-history-revealed-series-auth-sebastian-grant-auth-natl-usa-2-14-2022/.

[2] Curtis Tann, African-American Artists of Los Angeles: Curtis Tann, transcript of an oral history conducted in 1995 by Karen Anne Mason, Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, 1995, 15.

[3] Tann, 164.