Also in this series:

- Indigenous &: Not Always Looking West (with Brian Fleetwood)

- Indigenous &: Placing Practice While Being Displaced (with Teresa Faris)

- Indigenous &: Tradition Meets Technology (with Pat Pruitt)

All the interviewees in the Indigenous & series identify as Indigenous, and they all live in North America. The ampersand in the title serves as an opening. It invites discussion of parts of life that intersect, interweave, and interact with Indigeneity. These are visible in the artist’s studio practice. They can also be seen in the work they produce. That “&” is also a way to enter specificity in nation, gender, sexuality, and other aspects of being human.

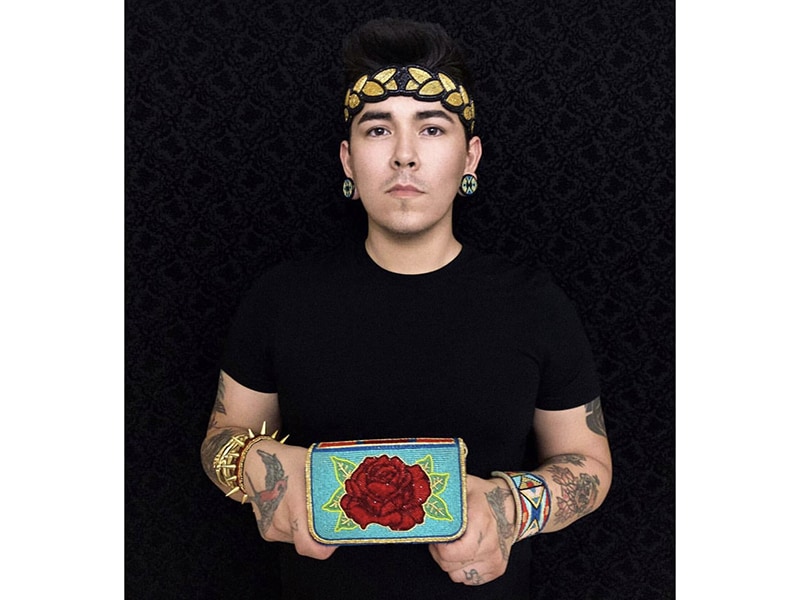

This is the third interview in the series. The first was with Brian Fleetwood, the second with Teresa Faris. Here, Elias Not Afraid talks about the material and technical knowledge that keeps him rooted in his culture while using that knowledge to make new or sometimes nontraditional images or forms. This navigation of the traditional and the unconventional opens another space for younger generations to become interested in learning techniques and applying them in new ways. Throughout the interview, Not Afraid talks about ways of learning and sharing that are as simple as getting in contact online. Because beading is usually not taught in-depth in university institutions, makers rely on each other and the always-developing digital space to refine and broaden their skill sets.

matt: As this series intends to celebrate Indigenous artists, what part of your background would you like to share?

Elias Not Afraid: I’m a member of the Apsaalooke (Crow) nation. I was born and raised on the Crow Indian reservation located in Montana. I’m a self-taught bead artist and fashion designer. I taught myself how to bead at the age of 12. I learned various other techniques over the years, revived a few “dead” beading techniques that had faded over the years, and created a few new techniques by experimenting. I’m a full-time bead artist (going on six years now).

I’ve been featured in multiple magazines, including in the centerfold of the February 2021 issue of Vogue magazine, as well as in articles on Vogue.com. My work is also in the permanent collections in museums such as the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Field Museum (Chicago), and the Smithsonian. It was also featured on the cover of book The United States of Fashion, by Vogue, and was included in the book as well.

Are any of the specific processes or aesthetics that you use specific to your tribal affiliation?

Elias Not Afraid: The foundations of my beadwork—the materials used, beading techniques, designs, colors, etc.—are what keep me rooted to my culture.

As I researched Crow beadwork from the early 1800s to the present, I slowly phased out my modern or contemporary supplies and materials and started collecting antique (1850–1920) and vintage (1920–1960) glass seed beads made in Italy, the Czech Republic, and France. When I had collected enough beads, I started using the same materials our ancestors used back when our tribe started beading. For example, I do all my beadwork on smoked deer hide brain-tanned by hand, and embellish the beadwork with items found/collected in nature, such as shells, bone, deer/elk/buffalo hide, horn/antlers, elk ivories, etc.

I come up with the colors and design on the spot and hardly plan things out ahead of time. When I get “beader’s block,” I pull out one of my many sketchbooks of designs and patterns (geometric and floral) that I have drawn in the past and throw something together that I haven’t used yet. I incorporate my own personal aesthetics, like punk/goth/high-fashion elements into the piece by adding metal spikes, exotic luxury leathers, fur, pearls, gems, etc.

Where/how did you learn the processes you use in your work?

Elias Not Afraid: Research. I researched the use of materials and the various processes by examining photos of beadwork in the collections of museums and archives. I also love challenging myself and my capabilities/skills. The best way to do that is by trying new things and challenging myself with colors, designs, and the use of materials to make something unique.

When making work to sell, do you have a specific audience or venue in mind?

Elias Not Afraid: Not at all, my work is for everyone. Once purchased, the owners can do what they want with it and wear it however they want. Purchasing from non-Indigenous businesses or selling Indigenous-“inspired” artwork is cultural appropriation. Buying directly from Indigenous artists is cultural appreciation. We need to normalize Indigenous beadwork as a luxury product.

You use elk ivories in your work. What are those, and what’s the significance of using them?

Elias Not Afraid: An elk has only one pair of ivories, in the upper jaw near the front of the mouth, where the canines should be. These have the same chemical composition as tusks on walrus, wild boars, and elephants. Fun fact: Hundreds of thousands of years ago, elk used to have tusks. Today, when an elk dies, after everything has broken down and disintegrated the only thing that will remain of the animal is the two ivories.

To Apsaalooke, the value of the ivories was equal to “diamonds.” I remember when I was younger and attending a bilingual summer school for Crow language, we were told that a man would give the ivories to his significant other to show his long-lasting love for them. The ivories would be made into a necklace or sometimes a bracelet. An Apsaalooke woman wore elk teeth on her wool dresses as a sign of wealth, to show that her husband/brother/father were good hunters and killed many elk. They might wear a dress adorned with 300 or more genuine elk ivories.

Nowadays ivories are mostly resin casts; the real elk ivories are hard to come by. I started collecting elk ivories four years ago and wanted to use them for a very special project. I finally used them on a beaded Apsaalooke-style cradle board. The straps and bottom part were covered in 80–100 real genuine bull elk ivories covered in a smoked elk hide. I entered it in the 99th annual Santa Fe Indian art market and sold the cradle board to the Smithsonian Museum, to be added to their permanent collections.

I’ve seen you making replica elk ivories to use in your work. What’s the difference between using replicas versus traditional materials?

Elias Not Afraid: I came up with the idea of making silicone casts/molds of the larger bull elk ivories I own. I mixed acrylic resin to cast them. They came out almost identical to the real thing.

I never used the resin elk teeth in any of my work, however. All the elk teeth on my work were genuine elk ivories.

Beadwork has long histories and traditions. How do you navigate or think about keeping a tradition alive while also exploring contemporary forms and imagery?

Elias Not Afraid: I love to bead nontraditional items likes skulls, snakes, or other kinds of animals or random imagery or iconography. I like to challenge myself to make designs very complicated or use a new technique with bright colorful old glass seed beads. (The older beads have many shades of colors that are no longer being manufactured today.) I’ll make a piece that will be “really cool to look at” and hope that our Indigenous youth see you don’t always have to bead traditional items. Hopefully they’ll become interested in learning how to bead so they can make something that they want to, and not be forced to bead only traditional/ceremonial items and designs. There are no gender roles in beading, it’s for both men and women, young and old.

What are some thoughts for the future? Is there a place you’d like to show or a project you’d like to make happen?

Elias Not Afraid: I have journals and note/sketch books full of ideas and designs of pieces I want to make—something different, something that hasn’t been done.

But for any project that I do, I first go for a walk or drive around and think of the project in my head. I start to deconstruct the item in my head and will sketch and write out the instructions of what I want to do. Once I get home, I start sketching the design out and do three rough drafts. I then narrow down the designs to one.

I prep my materials and start beading. The colors I don’t plan, I just make them up as I go. I work on the piece ’til it’s finished and always make slight changes as I go, based off my notes.

I’ve been beading for 18 years and have developed a lot of tips and tricks. I plan to eventually make videos and tutorials of what worked for me all these years and post them on YouTube for everyone. If people need help with beading, they should reach out to me via email or social media. I will help the best I can with their beading-related questions.

I beaded them on a layer of thin buckskin and layer of Kevlar. When I finished beading it, I lined the backs with multiple layers of Kevlar and smoked elk hide, photo courtesy of Elias Not Afraid

Where can people see more work or follow what you’re doing?

Elias Not Afraid: I’m on Instagram @eliasnotafraid and on Facebook @EliasJadeNotAfraid. I also have a website: www.ejnotafraid.com.

What other artists do you recommend checking out?

Elias Not Afraid: Molina Jo Parker and Noah Pino.