COVID-19 has drastically changed the way that instructors/jewelry programs around the world are teaching the upcoming generation. With a shift from studio- and technique-based learning, educators have had to adapt their curricula to accommodate the limited means of their students. From in-person instruction to remote learning, projects have evolved, exhibitions have shifted online, and found-object-based, recycle-/upcycle-focused material explorations have become the new standard for instruction. Last week, AJF published the first half of an essay in which Melis Agabigum, herself an educator, assembled brief vignette interviews with seven educators to discuss how they’ve adapted to their new teaching realities. The story continues here. (If you missed it, here’s Part 1.)

The contributors include:

- Leslie Boyd (Denver, CO, US), Assistant Professor of Art, Jewelry + Metalsmithing Area Coordinator, Metropolitan State University of Denver (MSU Denver)

- Sungyeoul Lee (Seoul, Korea), Assistant Professor, College of Design at Kookmin University

- Jorge Manilla (Ghent, Belgium), Head Professor Metal and Art Jewelry, Oslo National Academy of the Arts

- Lisa McGovern (Glasgow, Scotland), Curriculum Head of Craft & Design, City of Glasgow College

- Kerianne Quick (San Diego, CA, US), Assistant Professor of Art, San Diego State University (SDSU)

- Jess Tolbert (El Paso, TX, US), Assistant Professor of Art, Head of Jewelry + Metals, University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP)

- Jennifer Wells (Certaldo, Italy), Adjunct Faculty, Santa Reparata International School of Art, Florence

Melis Agabigum: There’s been an ongoing debate on whether schools should hold face-to-face, HyFlex (hybrid-flexible), and/or remote courses. While some institutions have committed to in-person classes, others are requiring courses to be available online. How do you see decisions like this affecting studio-based courses, and do you believe there’s a way to teach studio courses successfully online?

Leslie Boyd: I’m constantly considering how post-studio thinking and making can come into the jewelry studio and coursework as we move online. If we simply try to replicate what we’ve done before—try to offer the same curriculum—we will fail.

So do I think studio courses can be taught successfully online? Yes. Absolutely. We don’t have another choice. But we need to build them and be open to [the ways in which] they’ll look different from what they’ve looked like before, and furthermore we need to be excited about the possibilities, challenges, and growth in thinking that this shift will offer. If we aren’t excited and open to these changes, we won’t teach these new courses well. We’ve been disrupted and we owe it to our students to rise to the occasion, as difficult as it will be.

But this method of thinking isn’t well suited for every class or every school. Teaching an intermediate-level course within an interdisciplinary studio arts program is going to be a lot easier to adapt during this time than a beginning metals class at a school where most students are hoping to go on to work as designers or studio jewelers.

Sungyeoul Lee: I think it’s very difficult to teach studio courses successfully online. Traditional craft education requires many adequate tools and facilities, and since we usually acquire and hone skills via apprenticeship, there is certainly a limit for an inexperienced student to learn and polish skills through online video or books. Therefore, many people may think that continuous online studio class can reduce the depth of craftsmanship and degree of completion in their work. However, our society has been changing rapidly and has often seen the newest generation find hybrid styles more interesting and immersive than the values and traditions of craft. Moreover, they aren’t necessarily interested in serving a long apprenticeship to a craft practice. I think we can test the future of the craft education environment if we take it as an opportunity to test new changes or attempts in the craft of the newest generation rather than worry that COVID-19 will undermine the value of traditional craft education.

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: The CSU chancellor announced that most classes would be online, with the exception of labs, creative activities, and clinical classes related to licensing. At SDSU in particular, we’re adopting a HyFlex model where in-person time will be reduced, but students will still have studio access with safety and physical distancing protocol put in place.

Teaching studio courses online: You can learn about studio techniques, but we’re skeptical that studio classes can be taught successfully online. Visual art, and especially jewelry, is about first-hand experience, not only of the thing that’s made, but also of the process of making. No matter how good our demo videos are, there’s haptic/nonverbal information communicated by watching someone do and then doing.

As if the bias toward the visual isn’t enough in person, only showing work through cameras and on screens completely obliterates any tactile or spatial experience. Every 3D object becomes 2D. Even if the camera equipment available to us, as teachers, and to our students were cutting edge, it can’t create or replace the first-hand experience of feeling the weight of something in your hand, or understanding the materiality of something through touch.

Jewelry isn’t just an aesthetic visual experience, but a personal, three-way communication between maker and user through the object. Online teaching of studio classes is a Band-Aid for an amputation. A lot will be lost.

Jennifer Wells: I look to professionals such as Ricky Frank, who has been teaching enameling online via video for several years now. In this instance, he’s teaching people who already have at least a minimal studio setup, so the university system of teaching an introductory classes is different. I do think that a certain level of instruction can be achieved online, if it’s applicable and usable with the university system. I’m not sure. I think a great deal of what professors do is engage with students and create interest for the subject they’re teaching. If the drive isn’t there to learn a subject, I don’t think online teaching will spark it.

Accessibility, time, and emotional impact have become a prominent discussion in higher education, especially from a point of social equity. In what ways has the pandemic impacted your students or you, beyond not having access to a designated classroom studio? How have you worked through unforeseen or unacknowledged issues that may relate to accessibility?

Leslie Boyd: I spoke on a panel, hosted by ACC in April 2020, called Education Disruptions and Opportunities. My talk focused on equity cracks that were exposed by COVID-19. It’s worth giving the whole talk a listen![1]

Jorge Manilla: Well, I didn’t allow the pandemic to radically impact my students or me. The pandemic isn’t under my control, but while it does put limitations on me, those limitations are well under my control. So that was my starting point. I decided to use these limitations and create possibilities for exchanging ideas, collaborating with students and creating methodologies of work that fit the level of the students.

I couldn’t forget that what was under my control was the responsibility for finding methods of motivating students in a personal and individual way and not only creating assignments to keep them busy but something that enhanced their creative processes.

The students delivered projects and proposals that were quite interesting, and more or less in the same way I adopted different methodologies at different times, adapted for each level, taking into account that the needs of a lower-level student are not the same for a more advanced one. Some students didn’t have internet access or were unable to pay for it, so the school provided them with some internet data cards so that they could participate in the sessions.

This worked quite well for these initial months, but now I’m reconsidering how it will be in the future if we have to plan a whole semester in this way. Ideas continue to emerge, so I’m happy. What I consider extremely important is that we as teachers do not forget to create this based on the profiles of students we have at the moment and be more assertive in the efficiency of our study plans.

Lisa McGovern: A lot of students have suffered from mental health issues and feeling isolated from their friends at college. The emotional impact on them has been enormous as they have not only had worries about their health and their families’ health, but also their studies and how they were going to finish their work and get good grades. Our college had additional support systems in place during remote learning for students, alongside a college counselor, so we could direct anyone with personal issues to the right department.

Jennifer Wells: In our program, a major part of the students’ education is living abroad for a brief period, traveling and experiencing different cultures. The students were forced to leave midway through their semester and return to the US. Some were required to be in quarantine for 14 days upon return. It was a very jolting experience for them, and one for which they had little forewarning.

Looking into the future—beyond lending tools to students, or project flexibility, what kinds of ways can educators accommodate to restrictive situations such as lack of accessibility? Do you have any thoughts on this? Are there things that you’ve experienced that do or do not work?

Leslie Boyd: This is going to look very different for each institution. Is it private or public? A non-majors course, AA, BA, BFA, MFA? Commuter or residential? Is the program design based, readying students for a bench position, placed within an interdisciplinary studio arts program?

I teach at a large, open-enrollment, urban commuter campus with a BA and BFA program in interdisciplinary studio art. I’ve determined that I’m responsible for facilitating the following learning objectives within jewelry coursework (non-exhaustive):

- Critical and reflective thinking

- Knowledge of historical and contemporary practitioners and movements within the field of jewelry and metalsmithing

- Knowledge of the ways in which jewelry and metalsmithing processes have been used within the broader visual arts world

- The ability to contextualize the work one creates in response to the jewelry, craft, and visual arts fields at large, as well as in response to current events, struggles, and cultural movements

- Self-worth, pride, and accountability

- Processes and techniques that generally exclusively live within the field of jewelry and metalsmithing (soldering, stone setting, forming and raising, etc.)

Aside from the technical instruction, I feel that many of these goals can be pursued in a more accessible and equitable way than how many of our programs have historically functioned.

Pre-recorded lectures and supplementary texts, videos, podcasts, etc. can be made available to our students to access at times that fit into their schedule. Discussion boards, applications like Flipgrid, shared editable text-based documents, and individual or small group video meetings can supplement, or at times replace, group discussions. This flexibility gives individuals with jobs, child and family care demands, housing or transportation instability, etc., a fair shake. If the curriculum is built to accommodate flexibility instead of only being provided as a series of Band-Aids, then I believe we can do so with meaningful and comparable results.

Studio art, and craft-based disciplines in particular, are late to these conversations. Many argue it just can’t be done. (I have been and may, in some ways, still be one of those people.) I would argue that if we want to break down access and equity barriers within the field, then we need to keep at it. We need to dedicate time, money, and resources to make this work. COVID-19 has forced our hand. Let’s see this is an opportunity for growth.

Sungyeoul Lee: In recent years, many students in our program at Kookmin University have been doing elaborate modeling using Rhino3D, laser-cutting machines, and 3D printers, in addition to traditional modeling materials such as foam and clay. This allows students to test the structure and function of the outcome more accurately, and they can prepare for the works accordingly. We’ve encouraged students to find various materials and suitable processes for their work, and they boldly borrow from industrial technology processes. We occasionally let them use workshops located outside the school to produce the results they want. This approach was aimed at helping students understand how to produce more diverse craft works and products, but at the same time it has reduced their dependence on school studios.

Of course, in craft education, the process of learning and training work in school studios cannot be completely eliminated. I think we can find a way to teach crafts within a limited studio environment if we reduce our dependence on school studios while making balanced use of computers and online platforms, industrial equipment and processes, and external studio resources.

Beyond teaching, what kinds of unique formats have you or your students integrated into your curriculum to address critique and display of work?

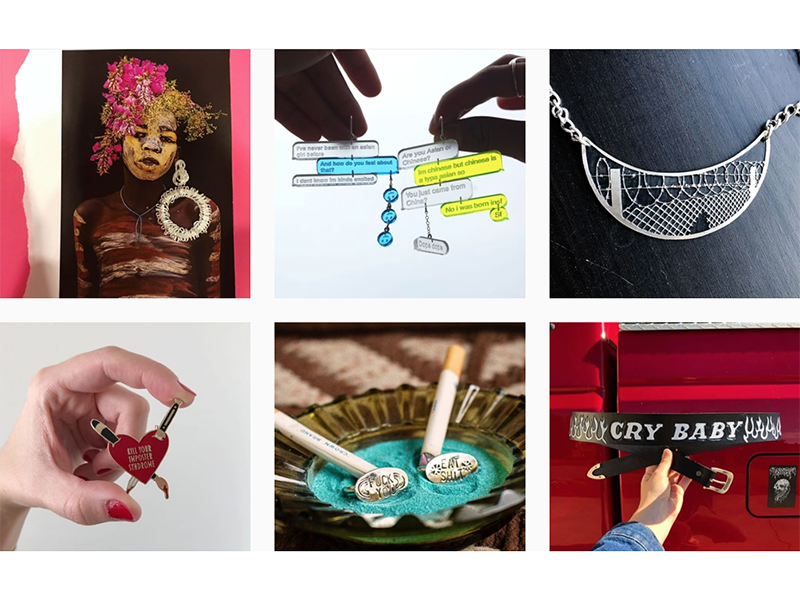

Leslie Boyd: My intermediate jewelry students curated “exhibitions” on Instagram, a project I will likely carry on post-COVID.[2]

Several intermediate jewelry students explored creating webpages as a platform for showcasing a specific body of work/line of inquiry, which I found really exciting. Discussing jewelry, identity, and value’s relationship to the internet and social media platforms while forced online and engaging with the class through a video platform sparked some really meaningful dialogue.

For critiques, we created shared word documents through Google Drive where students posted images and artist statements and we used the comment feature to pose questions and discussion points about the work before moving to a video critique. This worked well in making sure all students engaged in the dialogue, as I found that the shyer students were quieter than ever when we moved online.

Sungyeoul Lee: Although no specific evaluation or exhibition has been carried out yet, I’m planning to divide class into several small groups and video-record the process of critique with each group then upload it to the online campus to share it with other students. Additionally, pictures of works they’ve taken themselves will be exhibited online.

Lisa McGovern: Facebook groups have been a slightly more relaxed avenue of displaying work and giving feedback to students. Some of them have kindly donated pieces to the #supportthejewellerytrade initiative set up by TJA-Connect App. It means I can critique their work and they can scrutinize it more because they know it’s being sold for a good cause.

Supplementary online formats of in-person exhibitions or recorded artist lectures have been cropping up in recent years. In what ways have you incorporated nontraditional formats of displaying work into your curriculum?

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: https://www.instagram.com/artifacts.of.isolation/

Lisa McGovern: Our college is currently planning its first virtual end-of-year exhibition for students to submit their work. This is a great approach going forward as it gives the students a more global platform rather than confining the numbers to only those who can attend in person. Also, second-year students were encouraged to set up blogs. This is something they’ve been doing for a long time now… we’re extra grateful it works in this scenario.

It can be argued that the documentation process of a finished object is just as important as the object itself. How have you addressed documentation with your students?

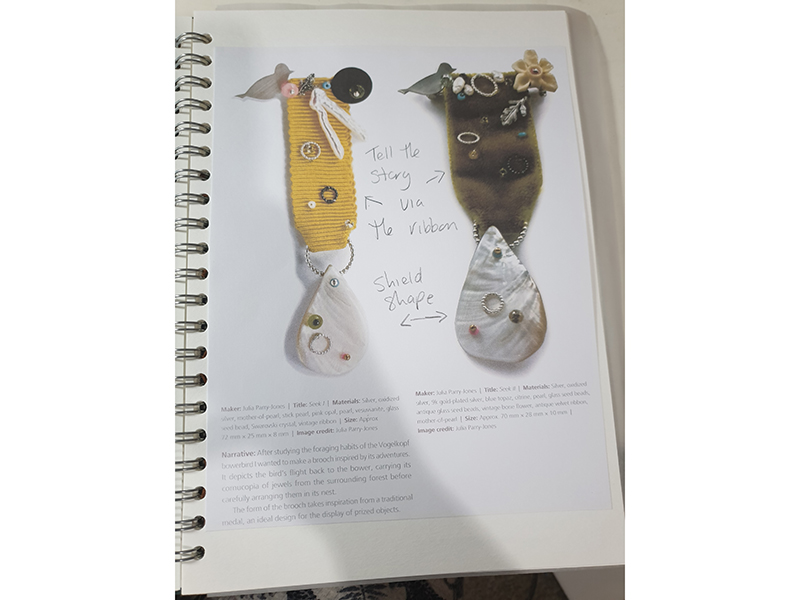

Leslie Boyd: We looked pretty extensively to contemporary jewelry as showcased on social media platforms such as Instagram for inspiration, as well as looking to fashion advertising strategies. How can the image contextualize the work? How can we create a platform, identity, or engage in “worldbuilding” to support or understand the work?

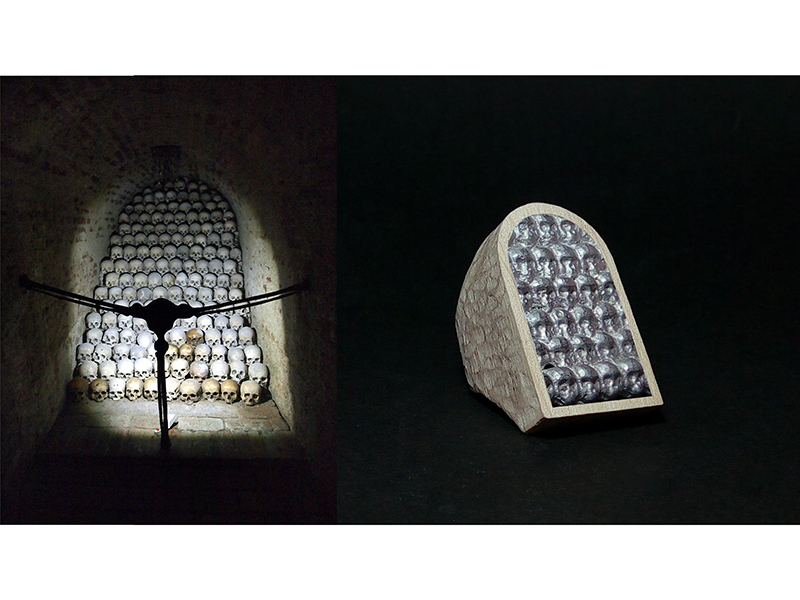

Jorge Manilla: The documentation process is extremely relevant. I always try to motivate my students by documenting the process as well. It’s extremely important to understand and see its evolution.And in this case, the total documentation helped the students to understand the atmosphere and character of their work. In documentation, they decide how they want the work to be seen, the position, the side or the detail that’s most relevant. Documenting the work teaches them to see the work from another perspective and share that perspective with the viewer.

Kerianne Quick and Jess Tolbert: That was a major component of our collaborative instruction. They weren’t just making jewelry, but images of jewelry. We never got the chance to hold, rotate, or examine the work up close in person as we normally would, so we discussed how they could best photograph the work, even with the limitation of their cell phones. We talked about how to portray the overall qualities of color, scale, wearability, etc., and also about content and contextualizing the work within their environments. And how photographing on the body, the position of the model, what they wear, what’s in the background can all add or detract from the information delivered by the image.

What other thoughts on anything related to pandemic teaching or being an educator during the pandemic would you share?

Jennifer Wells: Teaching for a study abroad program that works specifically with American students, we are not in the same situation to offer online courses, similar to what many American universities are doing this fall. For a study abroad program, part of the allure is to study abroad in Florence, Italy. The school I teach with had just built the jewelry studio in December 2019 and because they were forced to make drastic cuts, all the equipment was sent back and the jewelry studio is now closed.

Leslie Boyd: Full-time educators have an immense amount of privilege. For the most part we’ve retained employment and a paycheck through this pandemic. Many individuals (likely many of our students) remain unemployed and may be experiencing housing or food insecurity as a result. Social distancing can create circumstances where physical support systems are missing, creating further isolation and trauma. Sickness may have afflicted them or their loved ones.

Continue to have empathy. Continue to meet your students where they are. Provide the structure they may crave, with the flexibility they likely need.

[2] See MSUDenverCurates on Instagram.