April 13, 2010: Day One

At last, after a lot of planning, the Gray Area symposium opened at the Biblioteca de Mexico in Mexico City. For those of you who don’t know, the Gray Area is an ambitious project organized by the Amsterdam-based Otro Diseno Foundation for Cultural Cooperation and Development. As the program notes make clear, ‘Gray Area started as an urgent need: to diversify the international landscape of contemporary jewellery. Which turned into an idea: that of bringing enthusiastic jewellery devotees together in an unfamiliar, yet exciting place.’ Taking place over five days, the symposium brings together speakers from Europe and Latin America (with a sprinkling of other countries) in what is effectively an attempt at cultural mediation – to insert Latin American jewelry into a European and then global jewelry discussion.

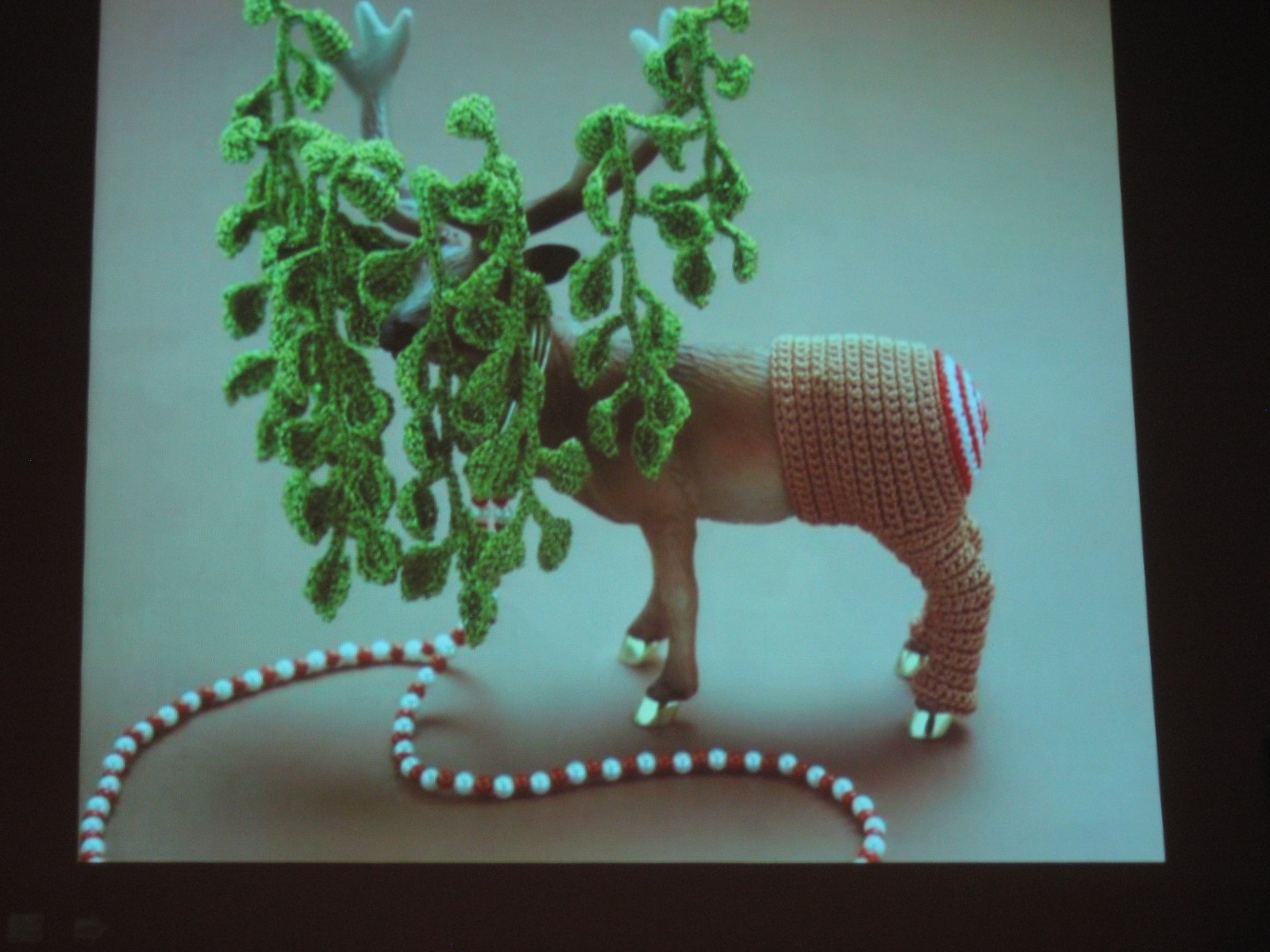

Dutch jeweler Manon van Kouswijk opened with a paper called ‘Gray Matter: No Brain, No Gain.’ Beginning with a whimsical reflection on her present position as head of jewelry at the Rietveld Academy in a building that is painted Rietveld grey, van Kouswijk effectively asked a series of questions that were designed to introduce the theme. What is the grey area? The space between commercial and art jewelry? Between craft and production? Between the head and the heart, the head and the hands? It was a nicely positioned talk in terms of the larger cultural dynamic of the conference, with van Kouswijk speculating on how a European can take part in a discussion located in a part of the world about which they know very little and asking what is left to exchange in a mediated environment when nearly everything is available in books or on the internet. Speaking in front of a steady stream of images pulled from different times and places, van Kouswijk’s paper was a plea for a subtly located making – quite different to her deterritorialized slide show, in which objects and images flowed together without regard for cultural and historical specificity.

The third talk of the morning, by Colombian archaeologist Clemencia Plazas, was called ‘American Cosmovision Through Metals,’, and turned back in time to the history of metals and technologies of pre-conquest Latin America. Her paper was a classic display of archaeology, coming with x-rays of objects, for example, so we could establish precisely how they were constructed and offering a series of close readings of objects in terms of manufacture and then the social or cultural uses to which these objects were put. Plazas discussed the symbolic potential of metals, such as gold and platinum, the ways in which these metals were worked and the types of jewelry or body adornment that were popular. Nose rings, for example, were close to breath, which means life. A spiral nose ring represented energy that penetrates and at the same time leaves the body and different forms of nose rings had aesthetic potential, disguising or obscuring the face in quite different ways.

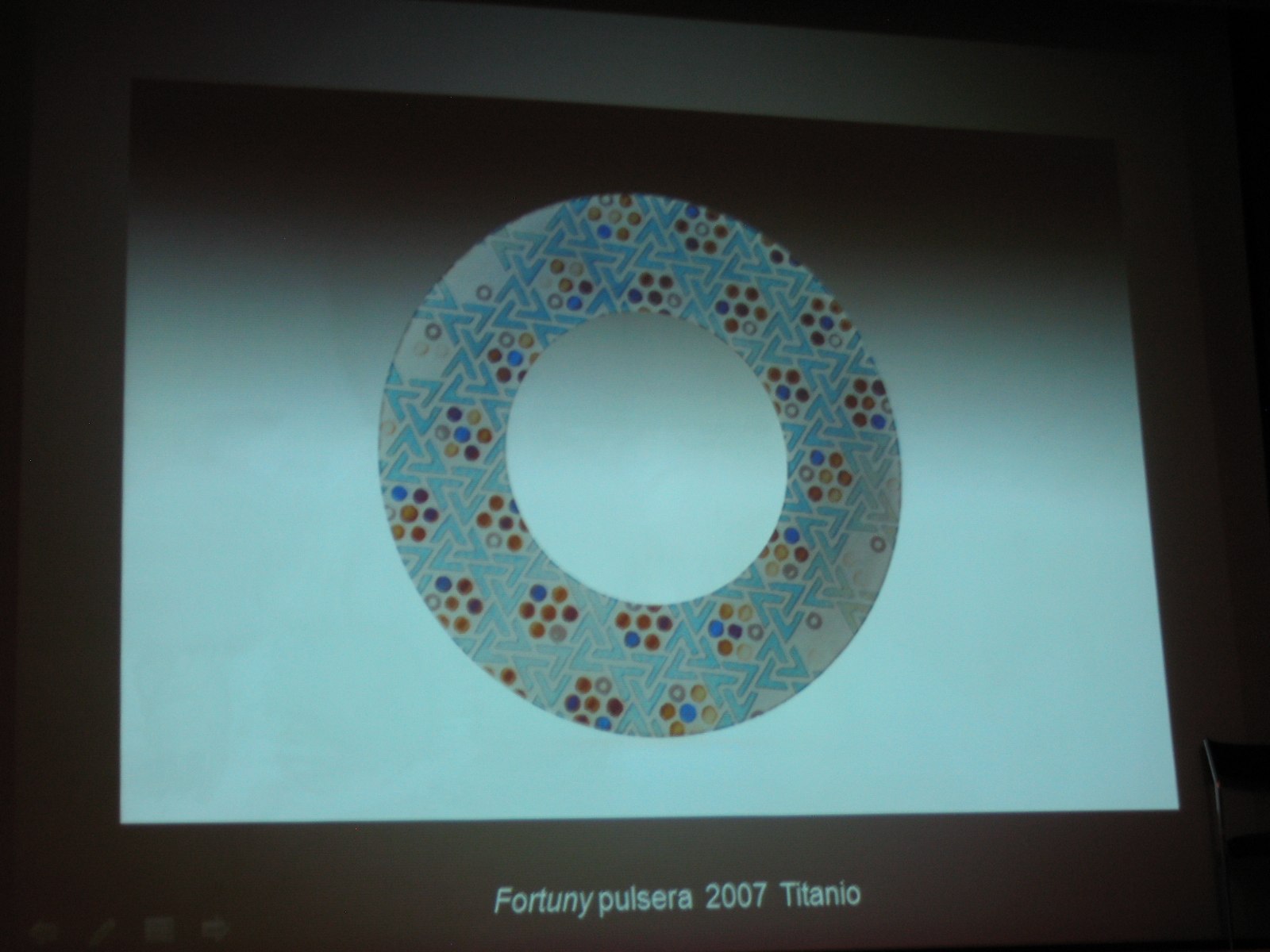

Spanish jeweler Ramon Puig Cuyas, who is head of jewelry at the Escola Massana, talked about the importance of materials to jewelry practice, suggesting that materials are critical to jewelry in a way that they are not for other fine art practices, like sculpture. The issue is not which materials, but that materials are the starting point – meaning that you cannot speak about jewelry without the language of materials. Jewelry has always been a vehicle for extraordinary symbolism, which is why humans have always looked for extraordinary materials to use for it. And he suggested that the dialogue of materials is what links contemporary jewelry to its past, to its jewelry traditions, even as it moves into the fine art world. As the scientist explores the nature of the materials of the universe to unlock secrets and knowledge of the world we live in, so the jeweler explores their materials in a similar way, with the same experimental intention and opportunity for discovery.

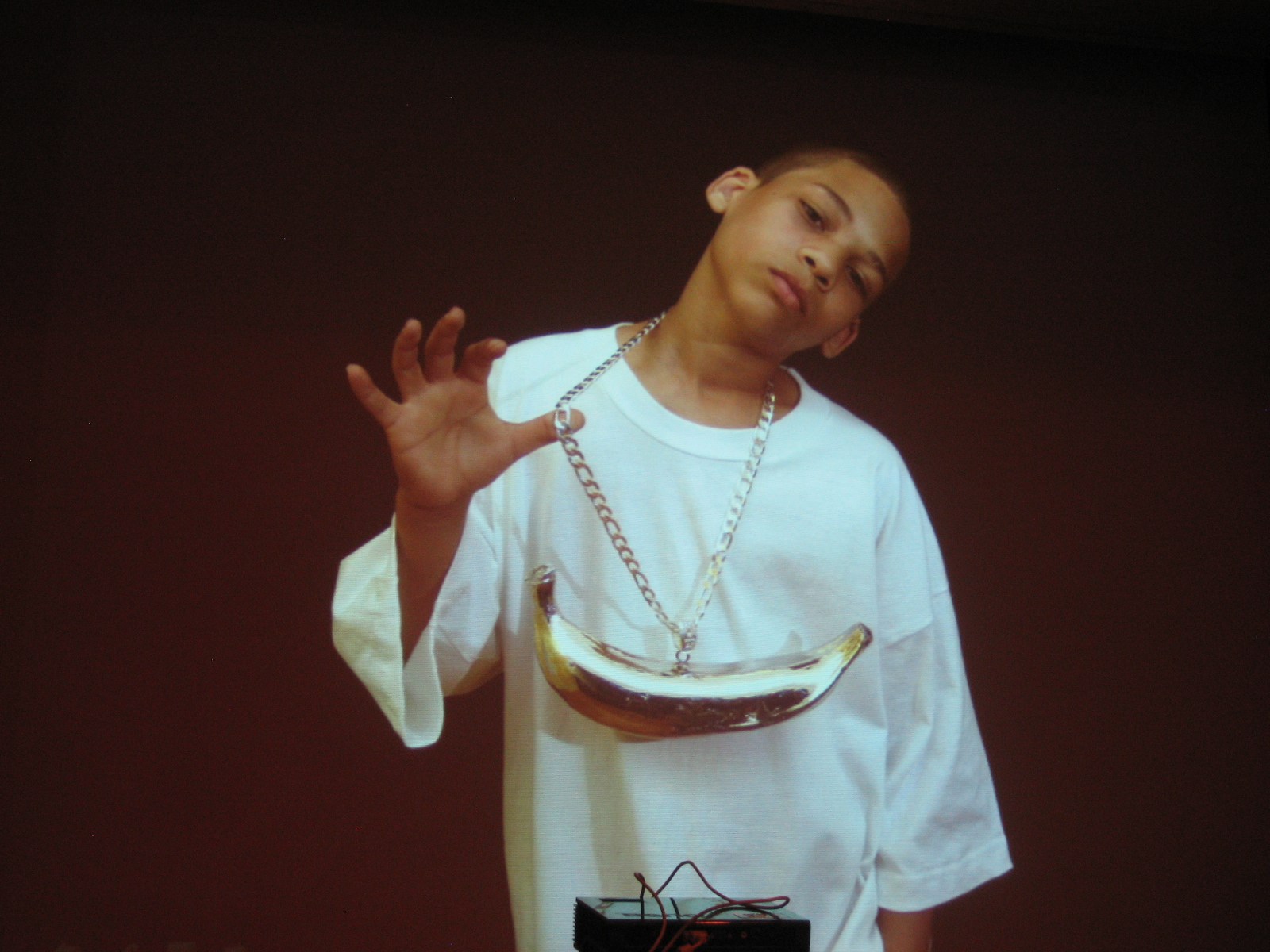

The final session of the day was a round-table discussion, returning to the theme of ‘What Does It Mean To Us?’ The participants were Liesbeth den Besten, an art historian from the Netherlands, French jeweler Benjamin Lignel, Mexican jeweler Jorge Manilla, who is a professor at the St Niklaas Academy in Belgium, Peruvian jeweler Ximena Briseno, who is currently studying in Australia, Mexican art critic Jose Manuel Springer, and myself (Damian Skinner). Everyone began by discussing the practice of contemporary jewelry in their country of origin and addressed, if only briefly, some of their questions and perspectives on the meaning of contemporary jewelry. Den Besten spoke about her notion of contemporary jewelry as a kind of faith, demanding belief and commitment, as opposed to design’s interest in seduction without commitment. Lignel talked about his background as a designer, his challenge to the doctrine of originality within contemporary jewelry and his belief that there is no requirement for him to make or fabricate his work. Manilla spoke about the importance of honesty and integrity in contemporary jewelry, which will guarantee the value of any given work. Briseno asked about the way in which contemporary jewelry in Latin America is engaging with jewelry practices from Europe and North America and whether this is a relationship of servitude, of unhealthy emulation. And Springer spoke about the personal potential of jewelry in constructing identity and the self and concluded that the value of contemporary jewelry is in its lack of easy classification, its liminal or intermediate role. This, he noted, is contemporary jewelry’s best quality, its most productive characteristic.

These presentations were followed by a period of robust discussion and questions from the floor, which debated the differences between contemporary jewelry and design (and the issue of how an object addresses needs and desires) the relation of art and craft (and the potential of jewelry in a time when fine art is seeking to become more relational, to move away from its autonomous status) and the double nature of jewelry as objects to wear and display.

Gaspar talked about the politics of centre and periphery, of being at the centre and being at the edge and the series of questions that come with this hierarchy: where is the idea of contemporary jewelry produced and managed and for whom? As she pointed out, these issues are not a problem for a European/Latin American encounter, but play a role in her experience as a writer and curator from southern Europe (Spain) traveling to central Europe (Germany, for example) where jewelry is dominant. As she tellingly suggested, when she visited the Schmuck exhibition in Munich in 1997 for the first time, she felt exotic, even though Barcelona had been a centre of contemporary jewelry since the 1950s. While she didn’t talk about this, the fact that she was curator of Schmuck 2010 must have been on people’s minds as one example of outsider successfully transforming their status into an insider – and a promising sign that the premise of the Gray Area project might be successfully realized.

One of the best aspects of Gaspar’s talk was the way she analyzed the Gray Area blog – the place where interaction between European and Latin American jewelers in the Gray Area exhibition took place – as a kind of fictional cartography, an imaginary space of encounter created out of various narratives (personal stories, stories of the workshop, stories of self and other, and stories of misunderstandings and mistranslations). While Gaspar was not insensitive to the politics of North/South interaction, with Europeans coming from an undoubted position of dominance, she also argued that the conditions of the interaction (such as the blog, the time zone differences, the use of English as a global language) have created a particular space in which the Gray Area takes place. This is not a space like the ones we each inhabit, but a new space/place brought into being by the conditions of the project. And these conditions are the causal factors for a new geography in which interesting things can take place. What was so exciting about this is that Gaspar provided a way to escape the conclusions of centre and periphery power relations, without acting like this dynamic isn’t a real problem. She provided, in other words, an agency for the Gray Area, an ability to act and to engage which was still informed and political and grounded in the real world.

It was interesting to have the opportunity to learn more about the various institutions in Latin America that teach contemporary jewelry and it was also notable how similar the philosophies of education were. The round table, then, was partly an introduction to the infrastructure of jewelry education in Latin America and partly a commentary about how contemporary jewelry should be taught, the issues that are impacting on education. It was less about how teaching institutions encourage formal and conceptual experimentation. One conclusion was that schools should be in advance of society, creating students for what the world will need in the future, not what is taking place now. And there was general agreement that trying to create contemporary jewelry specialists in three years is not going to work very well.

April 15, 2010: Day Three

Nuria Carulia, a pioneering contemporary jeweler from Colombia, gave a paper called ‘In Search of Identity: Contemporary Jewellery in Colombia and Its Contribution to the Craft Field,’ in which she surveyed the state of the field and gave an important insight to the infrastructure – or more precisely, its lack – that supports contemporary jewelry in many Latin American countries. One of the most interesting things she talked about was Colombian contemporary jewelry’s responsibility to cultural preservation and regeneration. She was not the first person to talk about this responsibility that contemporary jewelry seems to assume in Latin America and it was fascinating to see such a distinctive difference between contemporary jewelry in Europe and this part of the world.

Carulia talked about the importance of filigree in Colombian jewelry and its transformation from an import of Spanish colonization to an important expression of Colombian culture and identity. This theme was picked up in Ximena Briceno’s talk, titled ‘A Trans-Pacific Technique: Filigree in Australia.’ A two-part presentation in which Briceno discussed the history of filigree as an expression of complex cultural relations and trade and then her reinterpretation of filigree in her own jewelry in terms of her Australian context, Briceno’s talk was a good example of adornment’s complexity, of jewelry’s rich analytical possibilities, its historical importance.

The afternoon concluded with a roundtable tackling the ‘Management and Promotion of Contemporary Jewellery in Latin America.’ Featuring Marina Malinelli Wells (Argentina), Ofelia Murrieta (Mexico), Mirla Fernandes (Brazil), Monica Benitez (Mexico) and Carolina Rojo (Spain), the session struck an odd note with its focus on silver jewelry that seemed to be aligned much more with mass production and conventional design. This was not contemporary jewelry in the sense that this term has been used during the rest of the Gray Area conference. I found myself wondering if I wasn’t experiencing a potential misunderstanding that is growing as the conference progresses. If this is considered contemporary jewelry in Latin America, then we are talking about a very different kind of practice to what is meant by that term in Europe and other parts of the world. (E.g. the work that the speakers presented in this round table would never be accepted for the Schmuck exhibition.) This would suggest that those of us not from this part of the world require more history in order to understand correctly, since the notion of contemporary jewelry we import with us is clearly inadequate as a framework to understand contemporary jewelry from Latin America. And if this isn’t contemporary jewelry, then I am left wondering why the round-table didn’t address the subject of how contemporary jewelry is presented and promoted in this part of the world – an important issue if we are to map the potential of the Gray Area as a moment of dialog and transformation.

April 17, 2010: Day Four