This is an overview by Liesbeth den Besten of a day trip organized by AJF during NYC Jewelry Week. Den Besten is a member of the AJF board but has never been on one of the organized tours we regularly put on. Most of the members on the trip thought that the Met show was the most memorable. Bonnie Levine added, “Aside from The Met, my favorite venue was Sienna’s show, Kinship. I loved the juxtaposition of mid-century and new—I often couldn’t tell which was which. I loved the clean lines and simplicity of the work, old and new. It was classic and timeless. All of the work really sang to me.”

Raïssa Bump said, “I was surprised and delighted by the Breon O’Casey exhibition. I was unfamiliar with his work. Seeing so much of it in one intimate space helped me understand his expansive/diverse oeuvre and voice.” Sofia Bjorkman made this comment: “What I liked most is the mixture of things, the broad spectra of the field and the relations between everything. To see historical pieces is great when there are many contemporary ones, and vice versa.”

What follows are den Besten’s observations about what we saw on Tuesday, November 13, 2018, during NYC Jewelry Week.

There’s a first time for everything in life, and the New York AJF trip on November 13 during NYCJW was my first experience with an AJF trip—a thing that can be called a phenomenon after so many successful editions.

The trip started at the American Irish Historical Society, where we were introduced to the work of Breon O’Casey (1928–2011), in the exhibition Breon O’Casey, A World Unknown. The show was prepared in close connection with, and supported by, Helen Drutt, who represented his work in her Philadelphia gallery. The exhibition was a very good introduction to the work of this versatile artist, who started making jewelry in his studio in St. Ives and then moved to Cornwall, where he stretched his artistic practice into painting, printmaking, artists’ books, weaving, and sculpture.

The name of this British artist was known to me, but I was not quite familiar with his work. The rather archaic touch of his jewelry surprised me—I saw connections with ancient Sumerian jewelry, such as some necklaces with lapis lazuli (and gold), and with African jewelry. Other work, such as the hammered silver and amethyst necklace (circa 2000), had a more modernist flavor, while I fell in love with his silver cutlery (1998) and other rough-hammered forms. The graphic character of this work shows a sophisticated primitivism that invites you to touch and use the pieces. In 1998, O’Casey radically stopped making jewelry. At the end, his work and life were all about painting and printmaking.

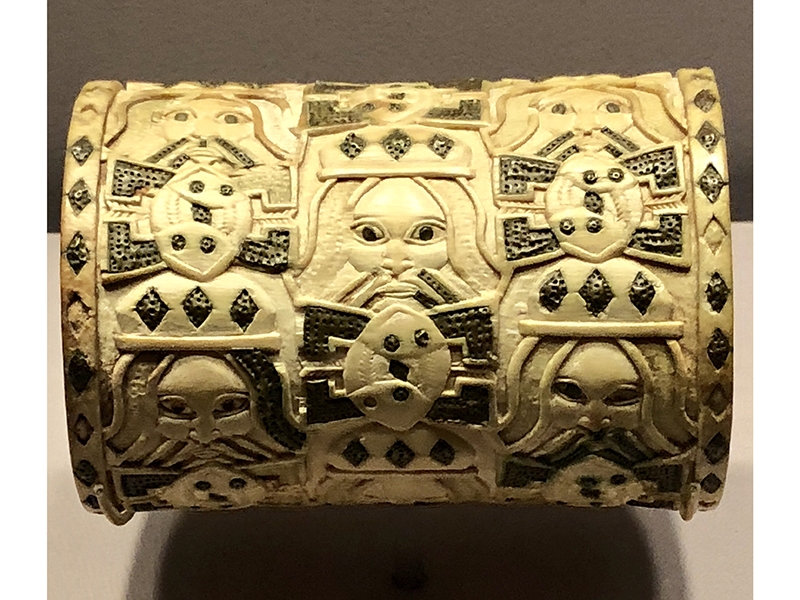

The next stop was The Metropolitan Museum, where the NYCJW team had arranged a curated tour by museum curator Beth Wees of the exhibition Jewelry: The Body Transformed. The tour was well organized. Wees showed us some remarkable pieces and showcases and talked about each piece or installation with enthusiasm and knowledge. This exhibition was my favorite venue. The exhibition was prepared over five years, by curators from five (or was it six?) different departments. It was divided into five sections: The Divine Body, The Regal Body, The Transcendent Body, The Alluring Body, and The Resplendent Body. From a curatorial and museum’s point of view, this is a mega effort, and innovative because the subject was approached from different perspectives (historical, archaeological, ethnological, social). This resulted in an exhibition that succeeds in informing the audience about the meaning of jewelry in the lives (and afterlives) of people throughout the history of mankind and on different continents. After seeing this beautiful and carefully set-up exhibition, people will understand that jewelry goes beyond mere decoration.

Today, unfortunately, it almost seems like something from the past to work for so long and with such a highly educated team of specialists on one exhibition. However, The Body Transformed proves how essential encyclopedic museums are in transmitting academic knowledge to the audience in an inspiring and understandable way.

Within this exhibition, the first room, where jewelry was exhibited according to the place it was worn on the body, and where there was room for confrontations between contemporary, fashion, design, ethnological, and antique jewelry, was my favorite.

At this point I would like to make one small critical note: Art jewelry introduced under the beautiful title “Redefining Resplendence” does not really come true. There are good examples exhibited, though, thanks to the gift of Donna Schneier in 2007. Some juxtapositions, such as Peter Chang’s bracelet and the antique Thai bracelet in one showcase, or Karl Fritsch’s ring, brass ornamented knuckles by Mira Mimlitsch-Gray, and the Renaissance pope’s ring in another case, were not only formally and aesthetically a joy but also stimulated thinking about the use of jewelry. However, in my view, the rather dim and solemn atmosphere of the entire show is not the right context for art jewelry.

Nonetheless, this exhibition is truly a treat, and I went back to see it again. The Met has an amazing jewelry collection from ancient times until today, and the database on the museum’s website is one of my favorite resources when preparing my jewelry history courses. To see pieces such as the gigantic gold Hellenistic armbands with sea gods from about 200 BCE in real life makes you aware how imposing they must have been when worn on someone’s arms. They also raise the question, “How can you wear such enormous ornaments?” and the answer can easily be found on the back of the bracelets, where there are suspension loops to attach the bracelets to the wearer’s sleeves. These facts are difficult to find in photographs, but they add to our understanding and appreciation of jewelry as human artefacts made for use, and of their meaning on the body.

The Hellenistic armbands are not the only item to show that size has been a theme in jewelry all through history. Also, the beautiful mosaic ear ornaments, representing winged runners, from Peru (5th–8th century), shown alongside the sturdy whale ivory ear ornaments from the Marquesas Islands (19th century), indicate that the ear in cultures far apart was perceived as a suitable place on the body to empower the wearer.

After a tasty lunch at the museum and some time to relax with other AJF participants, we visited Biba Schutz’s workshop, where she creates editions and one-of-a-kind jewelry. Although Schutz has worked as a jewelry artist since about 1970, her work is not well known in Europe. She had installed her pieces on a big table, each piece placed on piles of white A4 paper—a simple and informal way to show work. The improvised presentation and the jewelry itself was really enjoyable. Schutz’s playful, energetic work reflects her lively and informal personality. I especially liked her wirework and the exceptional link necklaces. In this Manhattan studio, the hustling and fitting started: excited people, mirrors, and credit cards.

The exhibition The Kinship Between: American Women Jewelers, organized by gallerist Sienna Patti and art dealer Mark McDonald, was shown at The Jewelry Library, a new hands-on exhibition space on the second floor of a commercial building. Of the seven female artists of different generations represented there, only Rebekah Frank and Noam Elyashiv have shown their work in European galleries on a regular basis. The others might be more obscure to Europeans. There were some wonderful modernist necklaces by acclaimed artist Betty Cooke (born 1924, and still active). Her jewelry has a universal quality and is still wearable today—as proof of this, I encountered an American collector wearing one of her beautiful necklaces from the 1950s two days later.

Margaret De Patta (1903–1964), who studied in 1941 under László Moholy-Nagy (former Bauhaus) at the School of Design in Chicago, was probably the most famous artist in this show. Known foremost as “the pupil of … ,” she gradually gained more respect after her rather early death. Her 2012 retrospective and the publication Space, Light, Structure, the Jewelry of Margaret De Patta (Oakland Museum of California and MAD New York) finally gave her the place she deserves in the history of art and jewelry, as the innovative jewelry designer she rightfully was. Her most stunning pieces, with rutilated quartz, faceted quartz, or moss agate showing her interest in translucency and light refractions, are held in museum collections, and were therefore unfortunately not part of this exhibition, but it was nice to have a look through the big collection of her sketches brought together by McDonald. Browsing through sketches and reading the notes brings the artist very close.

The setup of the exhibition was a bit cramped, but the idea to mix all the jewelry and create formal or material connections between jewelry pieces from different artists worked well. The combination of Raïssa Bump’s jewelry with de Patta’s was successful. Where de Patta uses quartz, Bump uses mica and mirror, but also crystal beads and silk to achieve subtle layered surfaces. One of my favorite pieces in this show is Bump’s sterling-silver necklace with five ornaments made of layers of mica, found objects, and silver ornamentation.

The last exhibitions we visited were located at two venues of Maison Gerard, an interior design gallery. Naama Bergman and Tamar Navama curated Parallel Lines, about contemporary jewelry from Israel artists who studied abroad—the parallel lines referring to their Israeli points of tangency. Among many good works, I appreciated Einat Leader’s necklace and the objects made of colorful tufted carpet, felt, and 24-karat gold—I had never seen this work before. The display of the jewelry on flat shiny black “dishes” placed on top of a huge oval marble table as if for a tasteful meal was nice and inviting. Next door, Loud and Clear: Voices from the Empire State, curated by Marjorie Simon and Biba Schutz, offered a wonderful introduction to the work of New Yorkers, “with their volume and volubility, their Babel of dialects, and their certainty in all things.” I was amused by Alexandra Lozier’s necklace, which combines classical refined glass beads with raw elements such as a skull, big crystals, and minerals.

This AJF trip was the best way to acclimatize and adapt to New York’s up-tempo rhythm and cacophony. A nice opportunity, too, to chat with people about jewelry, to see them fitting and buying, and hear their stories about it, and to study the program. The days after the trip were filled with visits to sometimes amazing and sometimes less convincing pop-up shows, shops, and museum exhibitions, with two bright stars among all the others still resonating with me after returning home and visiting yet more exhibitions and museums in Amsterdam and Antwerp. These stars: Denizen, by students and teachers of SUNY New Paltz, at the Hotel Chelsea under renovation, and the beautiful window exhibition White Gold, Clay Body, curated by Janna Gregonis and Brice Garrett, at E. R. Butler & Co., in Soho. Both shows presented an interesting choice of jewelry in a great setup.

There was so much to see, learn, and do in New York during the first New York City Jewelry Week, which was organized in only nine months’ time by Bella Neyman and JB Jones. From fashion to vintage, antique to xoxo chains, Hopi and Navajo to art jewelry, from nameplates to luxury jewels, from hip-hop to high-end jewelry brands, from exhibitions to events, from lectures to discussions, from workshops to demonstrations and gallery tours, I’m afraid I was only able to attend a fraction of it all.

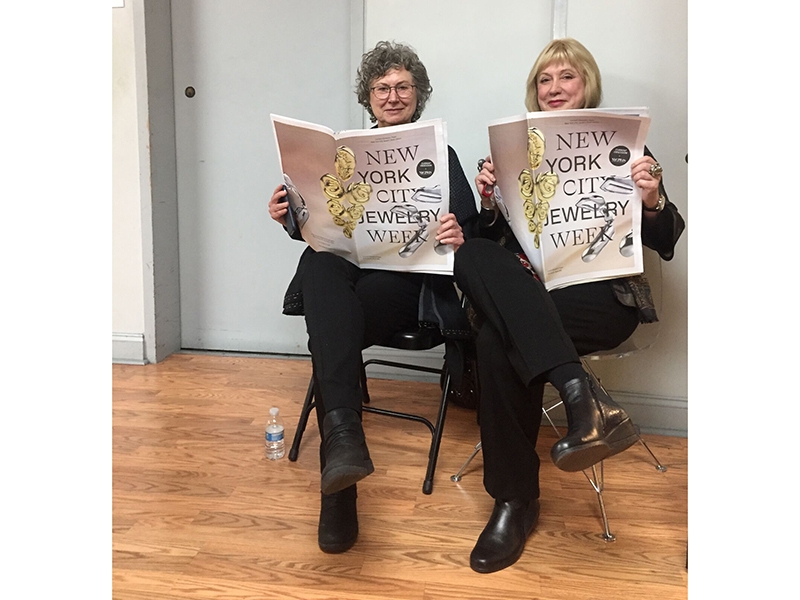

The NYCJW newspaper, produced by Current Obsession with good and informative articles about typical New York subjects, is a must-have, especially for those who couldn’t make it to NY this time. Get it here.