Critical Design Theory, a concept introduced by the British industrial designers and educators Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, emerged in the late 90s as a sort of conceptual successor to Anti-Design (its aesthetical successors being the Memphis group and Droog Design).

According to Dunne and Raby, Critical Design is not some sort of group or movement, but an attitude, a position that can be adopted by anyone, even by the people who have never heard of the term.[1] In the theory they developed, Critical Design is opposed to Affirmative Design.[2] Affirmative Design reinforces the status quo, while Critical Design challenges it. Critical Design aims to raise awareness, provoke thinking and actions, and start debates—unlike Affirmative Design, it asks questions rather than answering them.

Critical Design poses questions, some rather uncomfortable, and provokes reflection and starts debates—so basically it does what art usually does. Then how is it not art? It certainly borrows from some of its features and methods: the provocation, the shock, the metaphorical speech. But it doesn’t aspire to be art; moreover, art critique might even diminish Critical Design’s impact and meaning. For Critical Design to work, to commentate, to question, it has to be viewed as industrial design. Its whole power is in its proximity to everyday use. Design’s approach, think Dunne and Raby, should be in the ability simultaneously to appeal and to challenge—in the way a film or book does. The “appealing” part, however, doesn’t happen purely in the aesthetic field, or, at least, not altogether in the visually aesthetic. The “aesthetic of use,” according to Dunne, helps concentrate less on sculpture, the traditional reference for industrial designers, and more on the “complicated pleasure” of literature and film.[3] By complicated pleasure, they mean a type of experience that a person can get by not merely observing something, but understanding it and reflecting upon it.

For example, a project by Noam Toran, “Accessories for Lonely Men” (2001), is a collection of eight objects that are supposed to provide some of the “incidental pleasures of shared existence for those who live alone.”[4] The little machine called “The Sheet Stealer” pulls the bedclothes to the side of the bed; “The Chest-Hair Curler” is a steel finger that, while rotating gently, plays with its owner’s chest hair; another device breathes warm air in your face when placed on a pillow next to you; and so forth. Are those objects intended for production? Clearly not. But they are products for the mind—they make the viewer reflect on how the world should be in order for those objects actually to exist on a market. Dunne and Raby compare such designs to “physical synecdoche,” a part that represents the whole—“Accessories for Lonely Men” as a prop from this parallel world of lonely men that mysteriously appeared in front of us. One of the possible ways of looking at critical design objects, admit Dunne and Raby, is to imagine that they are props for nonexistent films: the viewer has to imagine his own version of the film world this object belongs to.[5]

Critical Design in Jewelry

Objects created by industrial design can have an infinite amount of different functions: they can brew your coffee, iron your clothes, measure your heartbeat, and connect you to the internet. The common factor is that they all are supposed to facilitate your daily life in some way—by actually taking upon themselves some of your routine tasks, or relieving you from boredom. Critical Design in the industrial sphere is known for its ability to make you imagine different kinds of life that can be facilitated, parallel-world life, if you wish, or possible and plausible worlds.[6]

Now, jewelry, regardless of its long history and regardless of the many forms and shapes it takes, has only two general functions—to decorate and to symbolize—and one general quality—to be valuable. It is possible on the rare occasion to find a contemporary jewelry piece that would work in the field of Critical Design exactly as an industrial design product would. (A perfect example of that is the Energy Addicts collection by Naomi Kizhner, where jewelry created from gold and biopolymer can be used to charge your electronic devices from your own bloodstream when connected intravenously. It sort of asks the question, “How much are you attached to your device?”). But for the most part, the typical Critical Design “what if” questions in the case of jewelry would be directed at its value, its decorative functions, and its ability to symbolize. What if jewelry were so precious because it was actually made of human flesh? What if in the future we were forced to wear jewelry that controls our facial expressions for corporate needs? What if together with engagements or coming of age, special jewelry pieces commemorated the death of a favorite Tamagotchi (a handheld digital pet)? What if we worshipped corporations and proudly wore golden Coca-Cola crucifixes? If we extend the “prop for a nonexistent film” metaphor to jewelry, the movie we end up with will be a sinister corporate dystopia—or an episode of Black Mirror, if you wish.

Jewelry That Decorates

Jewelry’s primary status has always been decoration of the human body. Beauty standards are different for every culture and every time period, and jewelry, together with fashion, keeps up the pace. However, if we talk about the clothing history of the Western world, jewelry changes with time are much less dramatic than the evolution of clothing itself. A lady in an 18th-century oil painting may wear a white wig and a deforming corset, but she will nonethless be wearing a pearl necklace similar to the one that your mother owns. An antique gold and ruby signet ring might look vintage today, but it won’t appear completely ridiculous and out of place on its modern wearer, unlike a pair of trousers with a codpiece, which would certainly raise some eyebrows. This stagnation of the field might be one of the reasons why by the end of 20th century, jewelry design started rapidly growing in all directions, in some of its shapes occasionally seizing the areas that used to belong to fashion. It seemed like Critical Design in the jewelry field suddenly felt responsible for everything that was wrong with beauty standards in general and had the urge to express its opinion on the subject.

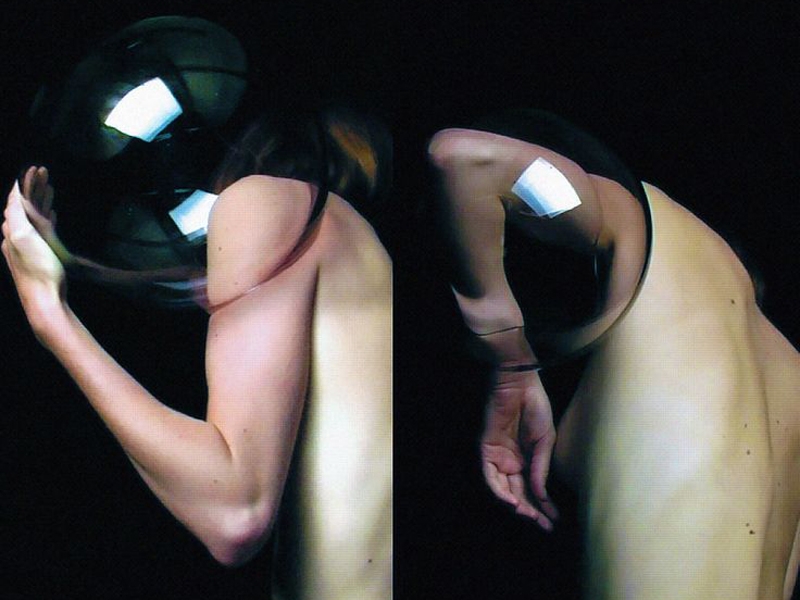

Violation of natural biological forms of the body could be a part of the process of the body’s social rationing—but if we talk about the strategies of “denormalizing” artistic expression, then one such strategy can be precisely bringing the norm ad absurdum: for example, the huge clown lips of the models at the Alexander McQueen ready-to-wear 2009/2010 show. “Reductio ad absurdum” is a popular method in Critical Design[7] and in the case of McQueen’s show it is used as if to ask, “Was this what you meant when you asked your plastic surgeon for full and sexy lips?” Ad absurdum can naturally be opposed to a more straightforward artistic method: the intentional creation of images of a “bad,” “wrong” body as a contrary to normative aesthetic prescriptions. A subtle example of such a work is one of the objects made by Naomi Filmer, a glass ball that, when put on the elbow of the model, forces her to always stand in an old woman’s bent, “sick” pose. Designer Annelie Gross also works with the violation of the norms of posing and posture. Linor Goralik, a Russian theoretician of fashion, writes that Gross’s collection Defects is made up of objects that in their structure remind us of exoprosthetics and medical corsets, but functionally force the wearer to stoop, hunch, curl in the embryo position, or fall over. The viewer in this situation is offered an extremely uncomfortable opportunity to feel himself in the role of a person who was forced into disability.[8]

Another jeweler who works with a metaphor for prosthetics is Christoph Zellweger. Zellweger compares the concept of jewelry in general with the idea of prosthetics: in his opinion, jewelry is for the body what a prosthetic is for the skeleton—it helps the body to function more fully, helps in its transition from functional to significant.[9] Zellweger claims that in our time luxury is not in jewelry anymore, but in the body itself, in the plastic surgery that is able to change it, to mold it until a perfect result is obtained. Adorning yourself from the outside is too retrograde for him. “The body,” says Zellweger, “becomes an artifact, a luxury product, because it becomes a matter of design.”[10] The jewelry pieces that Zellweger produces out of medical steel aesthetically remind one of prosthetics, of something that should be inside—but he instead places them outside of the body, offering a sort of new intimacy on the border line with exhibitionism.

The idea of the body itself transforming into jewelry instead of being just a frame for it was also important for Sissi Westerberg. In 2002 she created a bracelet/armband called Flesh—a plain and unremarkable silicone net that transformed the skin and flesh of the wearer’s arm into a pattern by tightening it in some places and letting it bulge in others.[11]

Several contemporary jewelry designers create body pieces that force the wearer to freeze in a certain pose, as if reflecting on our photo-centric era, when everyone we know gets photographed more often than any movie star of merely 30 years ago.[12] Jennifer Crupi, for instance, creates from sterling silver something she calls Wearable Sculptures—constructions that bring to mind lightly modified medieval torture devices that make the wearer stand with his arms crossed or form his hand in the gesture of a dancer. These objects affect or control the body’s movement and thus interfere with the wearer’s autonomy and therefore with their definition as a person.[13] Auste Arlauskaite created several mouthpieces in her collection Body Adjustments which deliberately put the wearer in a situation of discomfort, forcing his mouth into different expressions. Kristina Cranfeld, from the Royal College of Art, works in a similar way: she made a series of face objects called Ownership of the Face. One of them, a pair of huge magnifying glasses combined with a plastic mouth spreader, is, according to Cranfeld, supposed to be a speculative narrative “where the human face is an artifact that is highly commercialised and manipulated by external forces. The project portrays the future, where facial expressions of the workforce are exploited purely for corporate needs and to advertise a strong and successful company image.”[14]

Jewelry That Symbolizes

Traditional jewelry relays certain messages: “I’m engaged,” “I’m married,” “I turned 18,” “I’m a Christian,” “I’m a king,” “I’m a war hero.” Some of those things are reminders of the moments we cherish, others express our identity and remind us of what we’ve been through. The things, in other words, that are significant for us. Helen W. Drutt English writes, “Jewelry has a rich and complex subject matter: it has a long history of being intertwined with people’s imaginations. Jewelry is present in familiar rituals and institutions: engagement, marriage, the church, the military, […] coming of age, declaration of personal status and group identity.”[15] Those wedding rings, christening gifts, and gold crosses can be banal in design, but “the content of the ritual surrounding each of those objects lifts them above other mass-manufactured design.”[16]

The flourishing of conceptual jewelry, however, brought us examples of designers’ reflections on the subject of values that we find necessary to commemorate with jewelry. Imaginary “what if” questions of Critical Design sounded like, “what if there were a world where different things were celebrated?” and “what if those events could be celebrated differently?”

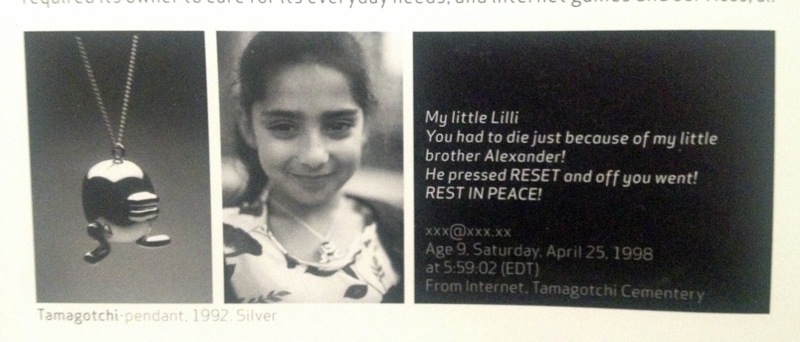

Cristoph Zellweger imagines a world where virtual death is as tragic as the real one, creating a highly polished, almost chrome-looking silver pendant in the shape of a small monster with a dedication to a deceased Tamagotchi pet: “My little Lilli! You had to die just because of my little brother Alexander! He pressed RESET and off you went! REST IN PEACE!”[17]

Another work that speaks about death is a set of brooches called Out of the Dark, by Mah Rana. She offers a piece of jewelry to be worn in mourning. The black textured surfaces of the discs slowly wear off, “revealing the gold beneath and marking the passage of time.”[18] They serve to remind the wearer of their loss but also mark the stages of the mourning, from grief to acceptance, with a physical transformation from darkness to light: “The permanence of gold then serves as a life-long reminder of a lost loved-one.”[19]

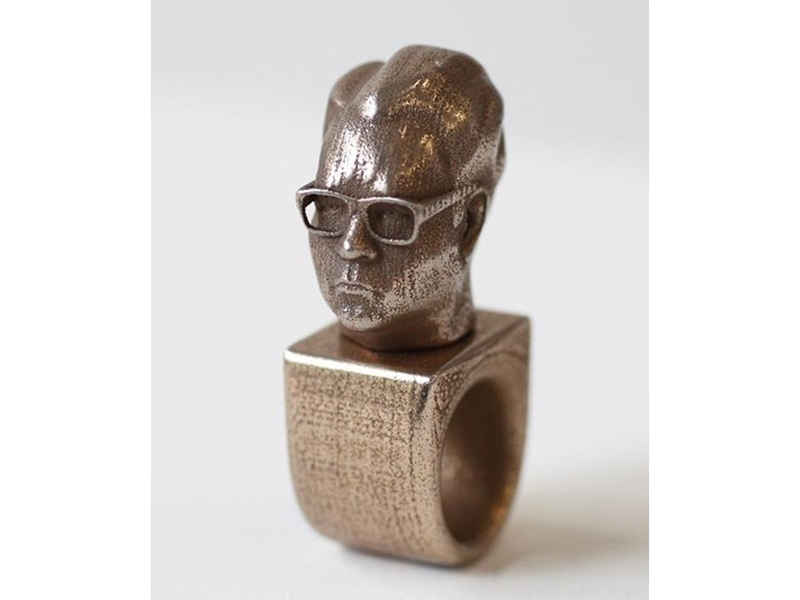

The famous Dutch jewelry designer Ted Noten invented his own symbol in his Mephisto bronze ring. This, he claims, will prevent him from possible bankruptcy, as it has Noten’s own head 3D-printed on top of the ring and—as the designer is sure—he is his own best salesman, “so why not play the devil’s advocate—Mephisto?”[20] The ring plays the role of a token in the egoistic era—and on top of everything else has a secret compartment “for a sniff of coke or a Viagra pill.”[21]

Tamar Paley offers an alternative take on medals. She’s talking about the modern perception of achievements and creates a 14-karat gold pin with a Facebook “like” sign. “Have you ever thought of how many ‘likes’ you give out daily?” asks Paley. “And what if you had only one ‘like’ to give as a medal to only one special person or for one occasion, who would you give it to and what for?”[22]

Religion, always being a subject of heated debates, also provided a topic for Critical Design in jewelry—and no wonder: the crucifix proved itself to be an object so widely used and abused that jewelers just couldn’t get past it. Dutch designer Pauline Barendse made a foldable crucifix named It’s Just a Box—it folds into a box and as a result raises the issue of religion as a mere cover for the emptiness inside. From afar, Frank Tjepkema’s Bling-Bling looks like an abundantly decorated cross, but if you take a closer look you can see that it is in fact made out of many thin layers of gold-plated steel, perforated to form a chaotic ligature of dozens of modern logos—from Nescafé and Apple to Playboy and Coca-Cola: “the world of capital loves to wrap itself in the illusion of timeless beauty.”[23]

Jewelry That Costs

Another imperishable quality of jewelry is its preciousness, which derives from the preciousness of the materials involved. However, except for, maybe, pearls, other “ingredients” that create the value of traditional jewelry are not “naturally” precious to us, not even in the monetary sense, for they have to be made precious by the expertise of craftspeople. But now a lot of designers who work in the contemporary jewelry field are choosing to work with nonprecious materials. Some of them make this choice merely to make their work less expensive in production, but others “opted for non-precious materials because they hated the values of wealth, status and power which they thought were wedded to gem-encrusted, precious-metal jewelry.”[24] All those material choices looked radical and rebellious when they just appeared—wood or plastic for instance—but now they look like an obvious choice and are even embraced by the jewelry industry. In order to keep making critical statements about traditional jewelry’s value, contemporary designers have had to turn to more radical materials: now “ingredients” involved in the making can vary from ready-made to matter of human origin like hair, skin, teeth, or blood.

The choice of using ready-mades is very popular among contemporary jewelers. It brings a wider context into a piece, offering a meta-view, reinforcing the designer’s statement about new values and preciousness by introducing a material that’s already “been there,” seen the industry, and been exchanged for money at some point of its life. It is man-produced in the same way that gold or gemstones are, so why shouldn’t it be used in jewelry?

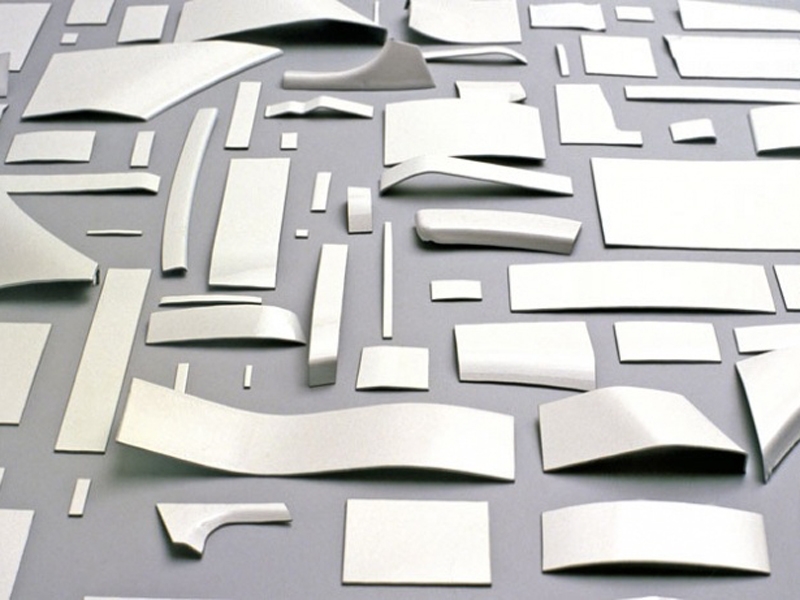

A striking ready-made collection was created by Ted Noten in 2001: he made a series of brooches that were cut out of an actual Mercedes Benz. The pieces are minimalist, highly wearable, and crafted with a great skill. They are successful jewelry pieces in their own right, but to know where they came from adds a completely other interpretative level to them. A Mercedes is not made out of precious metal, but its high value is indisputable in society’s point of view: Noten just replaces traditional preciousness with a modern one.

If certain materials are made precious by men, wouldn’t it be precious if they were made of men? Wouldn’t it increase their value even more? This kind of thought is behind those works that use human matter in their making. In 1995, Mona Hatoum made a beaded necklace out of her own hair. Serena Holm created a brooch, Hero in Vitro, that is made of a glass capsule filled with HIV-positive blood. The most striking example, however, is the Forget-Me-Knot ring by Sruli Recht, which is made of gold and upholstered with a strip of skin from Recht’s own abdomen. The video of the surgery is a part of the work, and the final product is for sale for €350,000—DNA certificate included.[25]

Another way of criticizing society’s obsession with luxury items is replacing the object of desire with a sign of it. This post-modern method is most effective when used on diamonds—which have a characteristic and recognizable shape. Ashley Buchanan makes rings with a laminated picture of the diamond on top, Trudee Hill made a giant two-dimensional metal ring called Taken, with an accentuated diamond shape, and Norwegian jewelry designer Sigurd Bronger’s Diamond Necklace is, in fact, a can of diamond spray hanging on a rope.

Sometimes, to criticize everyone’s lust for gold, actual gold can be used too, but in this case precious metal will re-create something very mundane, if not to say controversial. Nanna Melland, in her Decadence necklace (2003), cast in 14-karat gold a year’s worth of her own nails, and Ted Noten in 1998 started an amusing project, Chew Your Own Brooch, when he offered people to chew a piece of gum, send him the result in a box, and cast the results into golden brooches.[26]

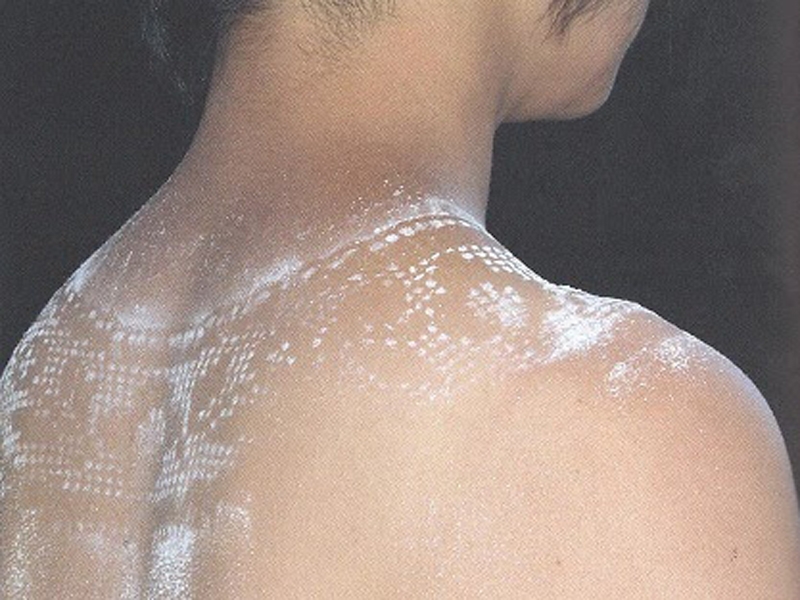

One of the reasons for gold’s high value is the fact that it is less prone to damage over time than other metals. The same is relevant for diamonds: “Diamonds are forever,” as the slogan from De Beers diamonds advertising once stated. Through preciousness of jewelry, its owners are craving immortality—and this is partly the reason why the concept of family heirlooms exists. Some contemporary jewelry designers are aiming directly at that issue, creating jewelry pieces that are deliberately fleeting, disappearing, existing only in the moment or over a short period of time. Millie Cullivan’s Lace Collar (2004) is a momentary work made lasting only by a photograph. An image of lace was traced onto the bare skin with white dust. “Transient, feminine, tender,” writes Caroline Broadhead about Cullivan’s work. “What’s left behind is a memory of touch, evidence of contact with the skin. There is an illusion of substance, but on recognition of its ephemerality, almost a holding of one’s breath so as not to disturb the image.”[27]

Contemporary jewelry might not always be recognized as art by the art community, but it undoubtedly falls under the definition of design, as it originates from a highly commercial field with its rules of production and distribution. We can assume that contemporary jewelry as a field to mainstream jewelry is the same as Critical Design is to commercial industrial design: both contemporary jewelry and Critical Design are rooted in the 60s but flourished and became a subject of theoretical studies and analysis several decades later. In whole, they research the same subject: What are the tendencies of our world and to what possible futures can they bring us? But if Critical Design in the industrial design field does it mostly through examining the possibilities of electronics and science, Critical Design in jewelry addresses the transformation of rituals and identities.

Bibliography

Astfalck, Jivan, Broadhead, Caroline and Derrez, Paul. New Directions in Jewellery. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2005.

Brun, Ines. Most Excellent: Jewelry Art for Heroes. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2016.

Dorman, Peter and Turner, Ralph. The New Jewelry: Trends+Traditions. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Drutt English, Helen W. and Dormer, Peter. Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession. New York: Rizzoli, 1995.

Dunne, Anthony. Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience and Critical Design. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Dunne, Anthony and Raby, Fiona. Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Boston: Birkhauser, 2001.

Dunne, Anthony and Raby, Fiona. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013.

Fishof, Iris. Jewelry in Israel: Multicultural Diversity 1948 to Present. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2014.

Gaspar, Mònica. Foreign Bodies: Christoph Zellweger. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University, 2007.

Goralik, Linor. “Body Deforming Objects and Costume Design as Social Art.” In Theory of Fashion 40 (2016).

Malpass, Matt. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative and Critical Design in Practice.” In Design and Culture 5 (2015): 333–356.

Malpass, Matt. “Critical Design Practice: Theoretical Perspectives and Methods of Engagement.” In The Design Journal 19 (2016): 473–489.

Parsons, Glenn. The Philosophy of Design. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016.

Willcox, Donald J. Body Jewelry: International Perspective. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1975.

[1] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 34.

[2] Dunne and Raby, “Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects,” p. 58.

[3] Crampton Smith, “Foreword to the 1999 Edition,” p. IX.

[4] Dunne and Raby, “Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects,” p. 63.

[5] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 89.

[6] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 5.

[7] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 80.

[8] Goralik, “Body Deforming Objects and Costume Design as Social Art,” http://www.nlobooks.ru/node/7327.

[9] Gaspar, “Foreign Bodies: Christoph Zellweger,” p. 10.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 114.

[12] Goralik, “Body Deforming Objects and Costume Design as Social Art,” http://www.nlobooks.ru/node/7327.

[13] Broadhead, “A Part/Apart,” p. 35.

[14] Cranfeld, http://kristinacranfeld.co.uk/Ownership-of-the-face.html.

[15] Drutt English, “Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession,” p. 14.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Gaspar, “Foreign Bodies: Christoph Zellweger,” p. 14.

[18] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 76.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Noten, http://www.tednoten.com/index.php/portfolio-items/mephisto/.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Paley in “Most Excellent: Jewellery Art for Heroes,” p. 50.

[23] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 14.

[24] Dormer, Turner, “The New Jewelry: Trends+Tradition,” p. 11.

[25] Recht, http://srulirecht.com/forget-me-knot.

[26] Noten, http://www.tednoten.com/index.php/portfolio-items/chew-your-own-brooch/.

[27] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 27.

***

2018年1月1日

仮定の世界からジュエリーデザインを考える

コンテンポラリージュエリーにおけるクリティカル・デザイン論

執筆: カティア・レイビー

クリティカル・デザイン論とは

クリティカル・デザイン論とは、アンチ・デザイン論の概念を引き継ぐ考え方として90年代半ばに登場した理論で、イギリスのデザイナーであり教育者でもあるアンソニー・ダンとフィオナ・レイビーの両氏が提唱したものである(ちなみに、アンチ・デザイン論の美的側面を引き継いだのは、メンフィスとドローグ・デザインだ)。

ダンとレイビーいわく、クリティカル・デザインとは、集団やムーブメントではなく、その名を知らずとも示すことができる、ある姿勢や態度である[1] 。両氏の理論によれば、クリティカル・デザインは、アファーマティブ・デザインと対極をなす[2] 。なぜならば、現状を強化するアファーマティブ・デザインとは異なり、クリティカル・デザインは、現状に疑問を呈し、自覚や思考、行動、議論をうながして、問いへの回答ではなく問いを立てることを目的とするからだ。

クリティカル・デザインは、時にかなり不愉快な問いを提示して考察や議論をうながす。つまり、基本的な役割は芸術と大差ない。では、どのような点で芸術と異なるのだろうか。クリティカル・デザインが、挑発や衝撃、隠喩的な発言などのいくつかの特長や手法を芸術界から借用しているのは確かである。だが、クリティカル・デザインは芸術たることを望まない。もっといえば、芸術批評は、クリティカル・デザインの影響や意義を弱体化させるおそれすらある。クリティカル・デザインが成立し、論評や問いを示すためには、工業デザインとしてみなされることが要件となる。なぜなら、クリティカル・デザインは、日常使いと緊密な距離を保ってこそ最大の力を発揮するからだ。ダンとレイビーは、デザインもまた、映画や書物と同様に、人を魅了すると同時に疑問を投げかけることで本領を発揮すべきと説く。ただし、人を魅了するさい、純然たる美的観点、つまりは視覚的な美しさという一点によってのみなされてはならない。ダンによれば「用の美」こそが工業デザイナーが長らく判断基準としてきた彫刻への依存を軽減し、文学や映画と同様の「複合的な快楽」により注力するための手助けになるのだという。[3]。ここでいう複合的な快楽とは、単なる観察ではなく、理解と考察を通して得られる種類の体験をさす。

たとえば、ノーム・トランによるプロジェクト「独身男性のためのアクセサリー」(2001)は、「一人暮らしをする男性に共同生活から得られる不意の喜びを提供する」ための8点の作品からなるコレクションだ [4] 。そのうち「シーツ泥棒」はベッドの片側からシーツを引っぱる小型の装置で、「胸毛カーラー」はスチール製の指が持ち主の胸毛にやさしく巻きついて戯れるものだ。ほかにも、隣に置いた枕にのせると、顔に温風を吹きかける装置などがある。これらの品々が量産を目的としていないことは間違いない。だが、このコレクションは、これらの装置が市場に出回ることができるとしたら、それはどんな世界なのかを見る者に考えさせる点において、人の心に作用する。ダンとレイビーは、そのようなデザインを、一部が全体を象徴することを意味する「物理的提喩」になぞらえる。そして、「独身男性のためのアクセサリー」について、孤独な男性が住むパラレル・ワールドの小道具が、私たちの目の前に忽然と現れたようだ、と例えている。ダンとレイビーが認めるところでは、クリティカル・デザインのひとつの見方は、実在しない映画の小道具だと考えることだそうである。つまり、見る者は、その物体が存在する映画世界を自分で想像せねばならないのだ[5]。

ジュエリーにおけるクリティカル・デザイン

工業デザイン製品の用途は、コーヒーの抽出や服のアイロンがけ、心拍数の計測、インターネットへの接続など、数かぎりないが、ルーティンワークの代行やひまつぶしなど、なんらかのかたちで日常生活をより円滑に進めるという点は、どの製品も共通している。だが、クリティカル・デザインについて言えば、円滑に進められるのとは違う生活、パラレル・ワールドの生活、ありうるかもしれない世界を私たちに想像させる力を持つからこそ工業界でその名を知られているのである。 [6]。

ここでジュエリーに目を向けたい。ジュエリーはその長い歴史や多様な造形にもかかわらず、装飾と象徴という二通りの基本機能と、貴重性というひとつの特質しかもたない。たしかに、コンテンポラリージュエリーには、工業デザイン製品と同じくクリティカル・デザインとして成立するものもまれにある(その好例が、ナオミ・キズナーによる「電力依存」だろう。これは、皮下接続を通じて自身の血流で電子機器を充電するための金とバイオポリマーでできたジュエリーで、「電子機器への思い入れの強さ」を問いかけている)。だが、大部分のジュエリーは、価値や装飾性、象徴性という点においてしか、クリティカル・デザインの基本である「もしこんな世界があったなら」という仮定の問いかけを発さない。しかし、もし本物の人肉製であるという一点において価値を持つジュエリーがあるとしたら? 企業のニーズを満たすために顔の表情を制御するジュエリーの装着を強いられたら? 婚約や節目となる年齢のお祝いと同様に、お気に入りのたまごっち(手のひらサイズのデジタルペット)の死を偲ぶジュエリーが存在するとしたら? 企業礼賛精神から金のコカ・コーラのマークを自慢げにつける世界がきたら? このように、架空の映画の小道具という例えをジュエリーにも当てはめると、お望み次第で、悪徳企業が跋扈するディストピア映画風のシナリオも『ブラック・ミラー』(訳注:Netflix配信のSFテレビドラマ)風のシナリオも生まれうるのだ。

装飾品としてのジュエリー

ジュエリーはこれまでずっと、身体の装飾を主な役割としてきた。美の基準は各文化、各時代で異なり、ジュエリーはファッションとともにその基準の変遷に足並みをそろえてきた。だが、西洋世界の服飾の歴史を見ればわかる通り、時代ごとのジュエリーの変化は、衣服の発展に比べるとずっと地味だ。18世紀の油彩画に描かれた貴婦人は、白髪頭のかつらをかぶり、その体はコルセットで変形していても、首から下げたネックレスは、あなたの母親の所持品とたいして変わらないはずだ。また、金とルビーでできたアンティークの印台リングは、年代物に見えはしても、現代人がつけたところで奇天烈で的外れには見えない。だが、コッドピース(股袋)付きのズボンをはいている人がいたら間違いなく驚愕ものである。ひょっとするとこの停滞ぶりこそが、20世紀後半になってジュエリーデザインが全方位的に急速な変化をとげはじめた理由かもしれない。その一部はこれまでならファッションが扱ってきた領域へも進出をはたしている。これはまるで、クリティカル・デザインが、ジュエリー界の美の基準全般から逸脱するものすべてに突如責任を感じはじめ、自己主張せねばと焦り出したようにすら見える。

身体本来の造形の侵害は、身体の社会的分配(※訳注:原文通り)の工程の一環と言えなくもない。だが、「標準からの逸脱」による芸術表現を考えるさい、「ad absurdum(※訳注:「滑稽なまでに」「不合理なほどに」を意味するラテン語)」の規範を持ち込むという戦略も考えられる。たとえば、アレキサンダー・マックイーンが、2009/2010プレタポルテコレクションでモデルに施した、唇から大きくはみ出たリップラインが特徴の道化師風メイクがそれにあたる。このような滑稽の概念にのっとった「背理法」はクリティカル・デザインの常套手段だ[7]。マックイーンのショーではそれが、「皆が整形して手に入れたがるぽってりしたセクシーな唇ってこれのこと?」という問いの形で用いられていたのである。当然ながら、この滑稽さ、不合理さは、標準的な美の基準に反する「悪しき」「不正な」身体イメージを意図的につくり出すという点で、直接的な芸術的手法と相反する。それをより婉曲的な方法で表現した例が、ナオミ・フィルマーによる球形ガラスの作品である。この作品を装着したモデルは、背中が曲がった老女の「病んだ」ポーズを強いられる。また、デザイナーのアンネリー・グロスもポーズや姿勢の規範の侵害を扱った作品を発表している。ロシアのファッション研究家、リノール・ゴラリックは、グロスの「欠陥」と題されたコレクションのオブジェ群は、人工装具や医療用コルセットを想起させこそすれ、機能面では装着者に猫背や海老反りのポーズや、背中を丸めた胎児の姿勢を強要し、モデルの転倒を招くと説き、さらに、その鑑賞者は、身体障害を強いられるモデルへの共感という、極度に居心地の悪い状況に置かされると続ける[8]。

ほかにも、人工装具の隠喩表現を用いるジュエリー作家には、クリストフ・ゼルベガーがいる。ゼルベガーはジュエリーの概念全般を人工装具の発想になぞらえる。彼は、ジュエリーは身体のため、人工装具は骨のためのものであり、人工装具はより完全に近い身体機能を実現し、単に機能するというレベルからの飛躍的な進展をうながすという[9]。彼は、現代の贅沢品はジュエリーではなく身体そのものであり、理想の容姿が手に入るまで整形手術で加工できるようになったと主張する。彼からすれば、外見上の装飾は大いなる退行なのだ。ゼルベガーは「デザイン次第でどうとでもなるという点で、身体は造り物や贅沢品になりはてた」と語る[10]。ゼルベガーによる医療用スチールのジュエリーは、その見た目から人工装具や体内に埋めこむ装置を想起させる。だが、彼はそれをあえて露出症的に体外で提示し、ある意味新たな親密性の境界を表現しているのである。

シッシ・ウェスターバーグもまた、身体はジュエリーのための単なる枠組みではなく、身体そのものがジュエリーへの変容をはたすという考えを重視している。彼女は、2002年に「ぜい肉」と題されたブレスレット/アームバンドを制作した。これはごく普通の網目状のシリコンだが、腕に装着されると、皮膚と腕の肉を締めつけて凹凸のまだら模様をつくりだす[11]。

コンテンポラリージュエリーの世界には、だれもが30年前のどの映画スターよりも写真に映る機会が多いという写真至上主義の現代を反映するかの如く、装着者を特定のポーズで拘束するボディピースをつくるデザイナーもいる[12]。たとえば、ジェニファー・クルーピは中世の拷問具の軽いアレンジ品を思わせる、「ウェラブル・スカルプチャー」と題したスターリングシルバーの作品をつくっているが、これを身につけると腕組みの姿勢を強いられたり、ダンサーの身振りをなぞった手の形を取らされたりする。これらの作品は、身体の動きに影響をおよぼしたり動きを制御したりすることで、装着者の自律性、ひいては人としての定義にまでも干渉する[13]。オーステ・アーラウスカイテは「身体調整器具」というコレクションで、さまざまな口の形を強要し、装着者にあえて不快な思いをさせる複数のマウスピースをつくった。ロイヤル・カレッジ・オブ・アートのクリスティーナ・クランフェルドも同様の「顔の所有権」と題したフェイス・オブジェクトのシリーズを発表している。そのひとつは、プラスチック製の口の拡張器と特大の拡大鏡とを組み合わせたものだ。クランフェルドは、この作品は架空の物語の産物だという。「その世界では、人の顔の商品化が過度に進み外部の力によって操作されています。このプロジェクトは、企業のニーズを満たし、有力で成功しているという企業イメージの喧伝のために従業員の表情が悪用される未来の世界を描き出しています」と語っている[14]。

象徴としてのジュエリー

従来的なジュエリーは「婚約者がいます」、「婚姻関係にあります」、「18歳になりました」、「私はクリスチャンです」、「私は王である」、「私は戦争で活躍して英雄になりました」といった特定のメッセージを伝える役割を果たす。その一部は、大事なひとときの記念品や、アイデンティティの表明、過去の出来事の記憶装置の役割を果たす。つまり、私たちにとって意義ある品々なのである。ヘレン・W・ドルット・イングリッシュはこう書いている。「ジュエリーが扱う主題は豊かで複合的であり、長く人類の想像世界と絡み合ってきた。ジュエリーは、婚約や婚姻、教会や軍、(中略)一定の年齢に達した記念、個人の立場や集団内の地位の表明といった、身近な儀式や組織において用いられてきた」[15]。こういった婚約指輪や洗礼の記念品、金の十字架はデザインこそ平凡だが「これらの品々は、それが置かれる儀式的な環境が持つ意味によって、その他の大量生産品以上の価値を持つ」のである[16]。

だが、コンセプチャルなジュエリーの台頭は、ジュエリーを記念品とする価値観を、デザイナーが問い直す事例をもたらした。ここでは、クリティカル・デザインの特長である「もしも」で始まる想像世界の問いは「この世界とは違う何かが大事にされる世界があったとしたら?」「特定の行事を別の方法で祝うとしたら?」という形で発話される。

クリストフ・ゼルベガーが思い描く世界では、バーチャルな死も実際の死とおなじ悲劇的な重みをもつ。彼は、死んだたまごっちに捧げるための、磨き込まれてクロム状に光る小さなモンスター型のシルバーのペンダントを作り、「弟のアレキサンダーがリセットボタンを押してしまったせいで消えてしまったかわいそうなリリー! どうか安らかに眠ってね」という持ち主のひとことを添えた [17]。

画像

クリストフ・ゼルベガー、たまごっちペンダント、1992年、スターリングシルバー、画像掲載は著者の厚意にもとづく

死を扱ったそのほかの作品には、マー・ラナの「アウト・オブ・ザ・ダーク」と題されたブローチ群がある。彼女が提案するのは、喪に服すためのジュエリーで、風合いのある黒地の表面がゆっくりと摩耗して「下地のゴールドが姿を現して時間の経過を表す」ディスク型の作品だ [18]。この作品群は、喪失の記憶装置としてだけでなく、悲嘆にはじまり受容にいたる故人への心境の変化を、闇から光への移行という物理的変化によって段階的にしめす役割もはたし「金の永続性が、愛する故人を生涯にわたって思い出させてくれる」[19]のである。

かの有名なオランダ人ジュエリーデザイナーのテッド・ノーテンは「メフィスト」[20]と題したブロンズの指輪で独自のシンボルを打ち出した。彼の主張によれば、破産しそうになっても、自分の頭を3Dプリントで再現して作ったこの指輪があれば大丈夫なのだそうだ。自分が自分の最高の宣伝塔であると自負する彼が、「みずから悪魔の手先になってやれ」と強く出たわけだ。この指輪は利己主義の時代を象徴する役割を果たす。しかも「コカイン一回分か錠剤のバイアグラ」をこっそりしまえる小箱にもなるというおまけつきだ[21]。

タマール・ペイリーは、一風変わった解釈によるメダルを提示する。彼女は現代ならではの達成感の表現方法に着目し、Facebookの「いいね!」マークをかたどった14金のピンを作っている。彼女は「一日に何回「いいね」を押しているか考えたことはありますか? 誰かひとりに一度しかメダルのかわりに「いいね」をあげられないとしたら、誰にどんな理由であげますか?」と問いかけているのだ [22]。

宗教はいつの時代も議論の的だが、ジュエリーの世界でもクリティカル・デザインについて考えるためのテーマを提供してきた。このことになんら不思議はないが、十字架は広く利用、濫用されすぎた。ジュエリー作家とてそれを無視するわけにはいかない。オランダ人デザイナーのポーリーン・バレンジは「これはただの箱です」と題した十字架をつくり、たたむと箱になるしかけを通じて、宗教とはただの覆いで、その内実は空虚である点を指摘した。フランク・チェプケマによる、一見すると派手な装飾が施された十字架である「ブリン・ブリン」は、よく見ると、ネスカフェからAppleにはじまり、PLAYBOYからコカ・コーラに至るまで、何十もの現代企業のロゴを透かしでかたどった薄いスチール板に金メッキを施したもので構成されているのがわかる。この作品には「資本主義世界は、時代を超えた美しさという幻想を隠れみのにしたがる」というメッセージが込められている[23]。

貴重品としてのジュエリー

ジュエリーが持つもうひとつの不変の性質は、使用される素材に由来する貴重性である。だが、おそらく真珠をのぞいて、伝統的なジュエリーの価値を作り上げてきた「素材」の貴重さは、金銭的な価値ですらも天然由来のものではない。なぜなら、それらの素材は、有能な職人の手を経てはじめて貴重品になるからだ。しかし、今は、コンテンポラリージュエリー界のデザイナーの多くが、自らの意志で価値の低い素材を使って作品を作っている。単に制作費の節約でそうしている作り手もいるが、「宝石を留めた貴金属のジュエリーと結びつきが強いと考えられる、富や地位、権力といった価値観が嫌で、あえて無価値な素材を選ぶ」作り手もいる[24] 。たとえば、木やプラスチックといった素材の選択はどれも、最初こそ先鋭的で反骨精神の表れとされたが、今では当たり前の選択であり、ジュエリー産業でも容認されている。今の時代に伝統的なジュエリーの価値を問う批判的な意見表明をし続けるには、さらに過激な素材に走らなければならない。そしていまや、既製品にはじまり、毛髪や皮膚、歯、血液といった人体の一部をも含む多岐にわたる物質が「素材」として扱われるようになったのである。

既製品の使用は、コンテンポラリージュエリーの作り手の間で人気が高い。産業界を経て、いちどは金銭的交換の対象とされた「既存」の素材を作品に取りこむと、作品の文脈を広げてメタな視点を提供し、新しい価値観に対するデザイナーの主張に強度を持たせることができる。既製品も金や宝石と同じ加工品だ。だとしたら、それをジュエリーに使わない手はない。

テッド・ノーテンは2001年に既製品を使って衝撃的なコレクションを発表した。本物のメルセデス・ベンツを切り刻んで大量のブローチを作ったのだ。この作品はミニマルで装着性が高く、高度な技術でしあげられている。それだけでもジュエリーとして立派に通用するが、その素材を知ると、まるで別の次元から作品を解釈できるようになる。ベンツ自体の材質は高価ではないが、社会的に見たこの車の価値の高さは明白であろう。つまり、ノーテンは従来的な価値観と現代の価値観との置換をおこなっているのである。

ある素材が人の手を経て貴重品に変わるのであれば、人からできた素材も貴重品となるのだろうか、そのことで価値は高まるのだろうか――人体を使った作品の背景にあるのはそんな考えである。1995年、モナ・ハトウムは自らの髪でビーズを作りネックレスにした。また、セレーナ・ホルムはHIV陽性の血液を詰めたガラス製のカプセルで「試験管の中の英雄」と題したブローチを作った。だが、もっとも衝撃的な作品はスルーリ・レクトによる指輪、「フォーゲット・ミー・ノット」(※訳注:英語のタイトルは、否定を意味するnotと結び目を意味するknotがかけられている)だろう。これは金の指輪の表面に、作り手自身の腹部の皮膚を張り巡らせたものだ。手術中に録画した映像も作品の一部で、DNA鑑定書込みの販売価格は35万ユーロである[25]。

贅沢品に対する社会の執着を批判するもうひとつの方法は、欲望の対象をその象徴と置きかえることである。このポストモダン的手法は、その特徴的で認識しやすい形ゆえ、ダイヤモンドに対して用いられた時に最大の効果を発揮する。アシュレー・ブキャナンはラミネート加工したダイヤモンドの画像を中石にみたてて指輪をつくった。トゥルディー・ヒルは、ダイヤモンド形が特長の「テイクン」と題した平面的な金属の特大リングを作った。そして、ノルウェイのジュエリーデザイナーのジグード・ブロンガーによる「ダイヤモンド・ネックレス」に至っては、ダイヤモンドのスプレー缶がそのままロープに下げられている。

本物の金は、時として金に対する万人の欲望を批判するために用いられるが、この場合、議論をかもすほどではなくとも、きわめて世俗的な物が金で再現される。ナンナ・メランドの「デカダンス」ネックレス(2003)は、切った後の爪を一年分ため込み、それを14金で鋳造したものだ。また、テッド・ノーテンは1998年「ガムを噛んでブローチをつくろう」という楽しいプロジェクトを立ち上げた。これは、噛んだガムを箱に入れて作家に送ると、そのガムを鋳造して金のブローチにしてくれるという企画だ [26]。

金が珍重される理由のひとつは、ほかの素材に比べて時間の経過による劣化や損傷が少ないという点だ。この特質は、かつてデビアス社が「ダイヤモンドは永遠の輝き」と宣伝文句で謳った通り、ダイヤモンドにもあてはまる。ジュエリーの所有者は、ジュエリー越しに永遠を渇望しているのである。家宝の概念が存在する理由の一部もここにある。コンテンポラリージュエリーの世界には、このテーマを直接扱い、あえて一瞬または短期間で消えてしまう作品を作るデザイナーもいる。ミリー・カリバンの「レースのネックレス」(2004)は、白い粉で肌に直接レースの模様を描いた、写真の形でのみ残せる一過性の作品だ。キャロライン・ブロードヘッドはこの作品を「はかなく女性的で優しい、触覚の記憶、肌に触れた痕跡だけが残る作品である。実体があるかのように錯覚してしまうが、一度その頼りなさに気がつくと、模様を壊さないよう息もほとんど止めてしまう」と評している [27]。

コンテンポラリージュエリーは、必ずしも芸術界から芸術品として認められないかもしれない。だが、独自の制作と流通の基準をもつ商業性の強いジャンルであるという点で、デザインだと定義できることは間違いない。私たちは、コンテンポラリージュエリーというジャンルが主流のジュエリーに至る道は、クリティカル・デザインが商業的な工業デザインに至る道と同じだと想定できる。というのも、コンテンポラリージュエリーもクリティカル・デザインも60年代に登場し、数十年を経てようやく、理論的な研究や分析の対象とされるようになったためだ。このふたつの領域は、「私たちが今いる世界の風潮とはどんなもので、またその風潮はどんな未来をもたらしうるのだろうか?」という共通のテーマを探索している。だが、クリティカル・デザインによるその可能性の模索方法は、インダストリアル・デザイン界とジュエリー界とで異なり、前者では主に電子機器や科学を通じて、後者では儀式やアイデンティティの変容を通じて行われているのである。

参考資料

Astfalck, Jivan, Broadhead, Caroline and Derrez, Paul. New Directions in Jewellery. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2005.

Brun, Ines. Most Excellent: Jewelry Art for Heroes. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2016.

Dorman, Peter and Turner, Ralph. The New Jewelry: Trends+Traditions. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Drutt English, Helen W. and Dormer, Peter. Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession. New York: Rizzoli, 1995.

Dunne, Anthony. Hertzian Tales: Electronic Products, Aesthetic Experience and Critical Design. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Dunne, Anthony and Raby, Fiona. Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects. Boston: Birkhauser, 2001.

Dunne, Anthony and Raby, Fiona. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013.

Fishof, Iris. Jewelry in Israel: Multicultural Diversity 1948 to Present. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2014.

Gaspar, Mònica. Foreign Bodies: Christoph Zellweger. Sheffield: Sheffield Hallam University, 2007.

Goralik, Linor. “Body Deforming Objects and Costume Design as Social Art.” In Theory of Fashion 40 (2016).

Malpass, Matt. “Between Wit and Reason: Defining Associative, Speculative and Critical Design in Practice.” In Design and Culture 5 (2015): 333–356.

Malpass, Matt. “Critical Design Practice: Theoretical Perspectives and Methods of Engagement.” In The Design Journal 19 (2016): 473–489.

Parsons, Glenn. The Philosophy of Design. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016.

Willcox, Donald J. Body Jewelry: International Perspective. Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1975.

[1] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 34.

[2] Dunne and Raby, “Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects,” p. 58.

[3] Crampton Smith, “Foreword to the 1999 Edition,” p. IX.

[4] Dunne and Raby, “Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects,” p. 63.

[5] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 89.

[6] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 5.

[7] Dunne and Raby, “Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction and Social Dreaming,” p. 80.

[8] Goralik, “Body Deforming Objects and Costume Design as Social Art,” http://www.nlobooks.ru/node/7327.

[9] Gaspar, “Foreign Bodies: Christoph Zellweger,” p. 10.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 114.

[12] Goralik, “Body Deforming Objects and Costume Design as Social Art,” http://www.nlobooks.ru/node/7327.

[13] Broadhead, “A Part/Apart,” p. 35.

[14] Cranfeld, http://kristinacranfeld.co.uk/Ownership-of-the-face.html.

[15] Drutt English, “Jewelry of Our Time: Art, Ornament and Obsession,” p. 14.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Gaspar, “Foreign Bodies: Christoph Zellweger,” p. 14.

[18] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 76.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Noten, http://www.tednoten.com/index.php/portfolio-items/mephisto/.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Paley in “Most Excellent: Jewellery Art for Heroes,” p. 50.

[23] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 14.

[24] Dormer, Turner, “The New Jewelry: Trends+Tradition,” p. 11.

[25] Recht, http://srulirecht.com/forget-me-knot.

[26] Noten, http://www.tednoten.com/index.php/portfolio-items/chew-your-own-brooch/.

[27] Asrfalk, Broadhead, Derrez, “New Directions in Jewelry,” p. 27.

カティア・レイビー:2012年、ロシア国立人文科学大学(モスクワ)哲学科を卒業。2017年シェンカー工学デザイン芸術大学(テルアビブ)のジュエリーデザイン科を卒業。イスラエルのコンテンポラリージュエリー界を振興すべくブログ「シャイニーズ、トリンケッツ&クレイジー・シット」を立ち上げ、ロシアメディア向けに複数のレビューを執筆。ジュエリーデザイナーとしても活動しドイツとイタリアでの展覧会に出品。またロシアやイスラエルの雑誌にも作品が取り上げられている。