Each year, Art Jewelry Forum organizes a trip for collectors, curators, and enthusiasts to visit one or two cities to tour jewelry galleries, visit artist studios, and explore museums with jewelry collections. In 2016, the AJF group visited Florence and Padua, Italy, and had an insightful studio visit with Annamaria Zanella. We wanted to share a bit of that encounter with you. Roberta Bernabei’s interview with Annamaria Zanella gives you a taste of the AJF group experience. Enjoy.

Roberta Bernabei: It’s always interesting to know what prompted an artist to study jewelry. You originally wanted to study fashion and subsequently fell in love with jewelry. Could you describe this progression?

Annamaria Zanella: I was a student at the Istituto Pietro Selvatico of Padua in the goldsmithing department. My initial intention was to study textiles and fashion, but there were no spots left. Therefore, I decided to stay in the goldsmith department for one year and then switch to textiles the year after. That year, before Christmas, the whole year-group went with the jewelry design teacher to visit Adelphi—a gallery of fine art in the town center of Padua. I was so fascinated and struck by the pieces of jewelry there that I decided to stay in the goldsmithing department for the whole five-year course. An exhibition can change your life, and this is what happened to me.

You studied under famous Paduan maestros such as Francesco Pavan, Giampaolo Babetto, Graziano Visintin, and Renzo Pasquale. You’ve mentioned Pavan’s encouragement and his particular technical abilities in previous interviews.[1] How did the other teachers inspire you?

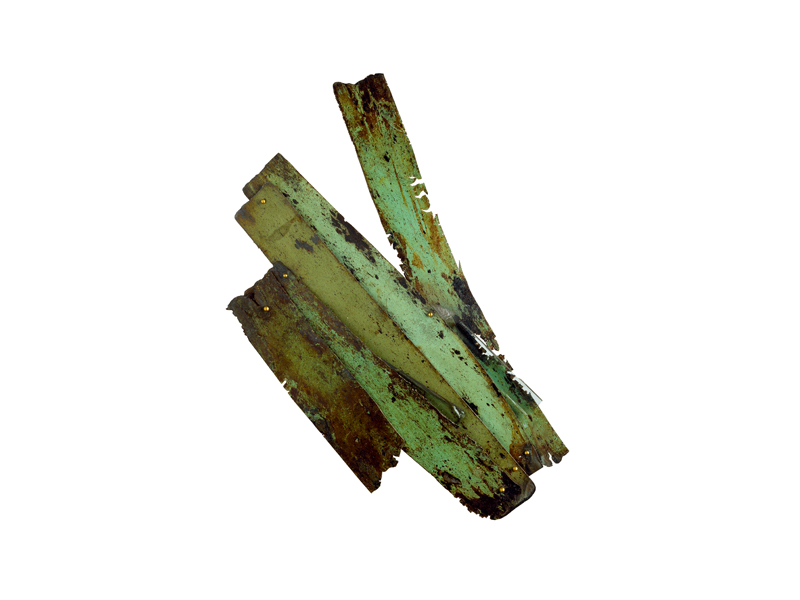

Annamaria Zanella: Pavan was, for every pupil in the school, a special teacher. He understood difficulties and hesitations, he provoked responses when we spoke about a piece of jewelry that was only just finished—emotional reactions that stimulated one to go “beyond.” He saw my first pieces of jewelry on enameled iron and was fascinated. He believed in those rusty metal sheets at once, and I’m very grateful.

He pushed me to advance my own creative place and to create a personal language. This has been an important endorsement for my artistic research. The whole teaching team at the institute had strong personalities and determined a style where the study of forms and geometry was a necessity of expression common for everyone.

Your interest in Arte Povera was initiated by your studies at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, and you have stressed the link between found objects or discarded materials and the creation of jewelry. Could you tell us about the relationship between these materials and making wearable objects?

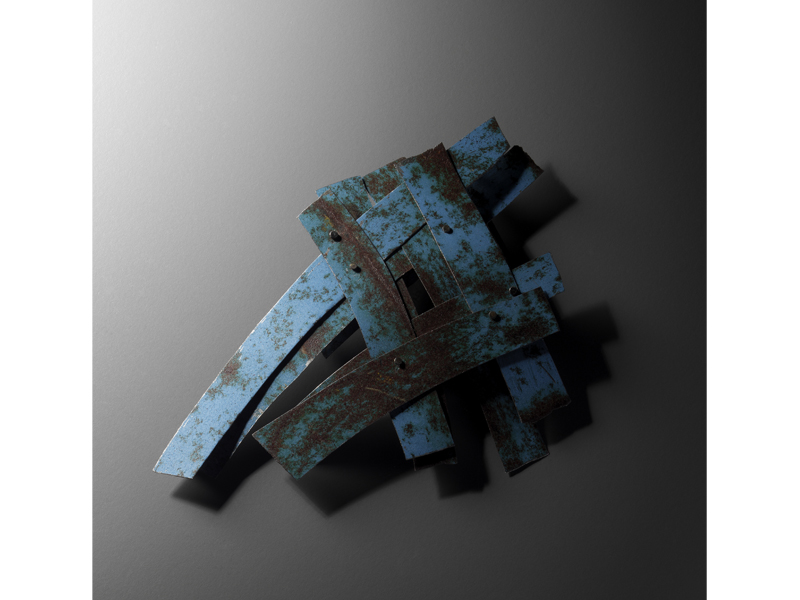

Annamaria Zanella: I studied the Arte Povera Italian movement for an exam at the academy, and this made me view things in a different way, even in regard to art jewelry. I was fascinated by how the artists of this extraordinary movement abandoned canvases, brushes, hammers, and scalpels—revolutionizing the means of expressing themselves by favoring gestures, concepts, and performances. The artists of Arte Povera utilized materials that had never been considered in art before, such as rags, plastics, broken glass, etc.—even live animals in the gallery.

I understood that even in jewelry, it was necessary to consider the thought that has to go beyond form. The title of the piece of work becomes an integral part of the work itself. Ever since the first pieces of work, I have tentatively tried to give new impulses to the jewelry, so that it’s no longer solely a means with which to decorate the body as an end in itself, but rather that the work should express an emotion, provoke and communicate a concept beyond the preciousness of materials. I tried to detach myself from the minimalist and geometric research of my maestros, in order to elevate jewelry to a more conceptual form.

In reference to your latest work, what is the idea or concept behind the body of work and its strong use of colors?

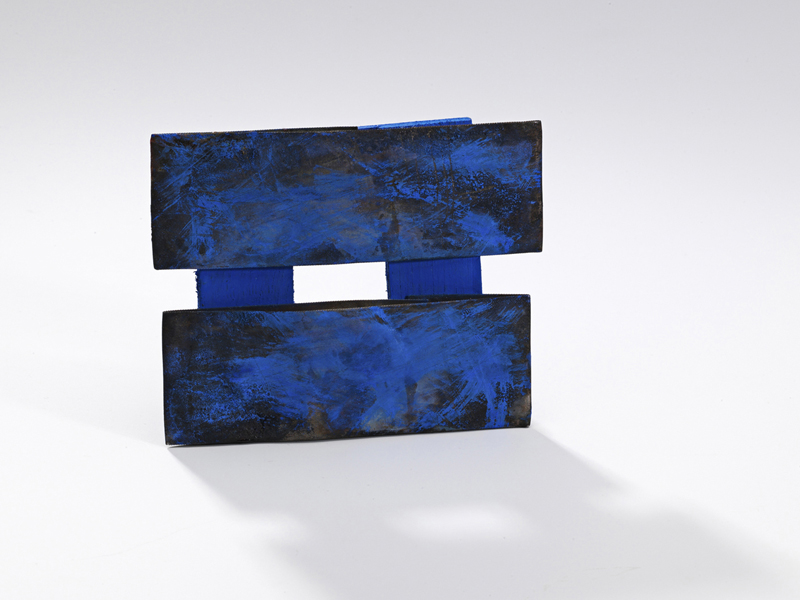

Annamaria Zanella: Color is an emotion. Color is, for me, what stimulates the vision of the piece of work in its entirety. I cannot think of a piece of jewelry without color, without enamel or pigment; sometimes the color of metal is too cold. I love the color of rust … oxidized iron is a chemical reaction that brings a marvellous unity and togetherness of colors, it’s an unpredictable alchemy of oranges and reds. Color is my answer to problems that afflict everyday life. If we wear a red and blue brooch, this might have a mystic meaning.

I’ve been studying the story and history of color. I’ve read all the books by professor Michel Pastoureau, lecturer of medieval history at the Sorbonne in Paris, who is a luminary in this research topic. For about two years now, I’ve been interested in the history of colors, and above all blue.

Blue took on relevance from low medieval times onward. For example, before the year 1200, the Virgin’s mantle was always depicted in white. When the Florentine painter Giotto came to Padua to work on the frescoes of the Scrovegni Chapel (1303–1305), he ordered gold and lapis lazuli in equal quantities, as well as the blue pigment called oltre mare (beyond the ocean), which came from the mountains of far-off Afghanistan, and which was valued as highly as gold. Giotto painted the vault of the chapel as if it were a starry sky, with lapis lazuli pigment (and azurite). He applied the blue pigment to the surface with the fresco technique, together with natural binders.

Blue is the color of transcendence and spirituality, used by many artists through the present day to represent the spiritual (for instance, Wassily Kandinsky), beauty, and the sublime, even in their most abstract forms (Yves Klein and Anish Kapoor).

It was from these thoughts that I created this collection, in which blue becomes the jewel itself. In these six pieces, I prepared the “beyond ocean blue” pigment exactly as painters had until the 18th century, by grinding it very finely in a porcelain mortar and then applying it to the jewel with natural binders (egg yolk, honey, rock alum, etc.), following 14th-century recipes. This is a kind of combined alchemy between contemporary materials (steel fabric, titanium, iron) and a mineral which, as in a painting, recalls the depths of the heavens and of the sea. Blue confers a poetic significance on an object, and we, the observers, are asked to reflect on it, to “go beyond the ocean.”

Could you describe how a piece is conceived and then finalized to be worn?

Annamaria Zanella: The idea of creating a piece of jewelry is born from the need to communicate to others my interpretations of the events that surround me. I attempt to capture moments, much as a photograph does. The emotion, the thinking, is crystallized in the piece of jewelry. It’s difficult to explain how my work emerges, sometimes … the absolute emptiness, and then, while driving around the countryside where I live, I might see a Palladian villa, a wooden door worn out by time, a dilapidated wall, a torn publicity poster consumed by the rain, a colorful fruit basket at the Paduan market, a movie, or a concert. The idea of the piece of work is developed during long periods of reflection and silence, or … suddenly as the result of the saturation of a multitude of inputs stored in my head. It’s difficult to describe what happens to me when I create, I take notes, I draw, I sketch on pieces of papers here and there, a bit untidy. Emotions come from people that I meet, the journeys I make, news I read in the newspaper, books I read … everything is transformed and translated into forms and colors.

There’s nothing scientific in any act of creating—when the light is switched on in the heads of any artist or creative. It’s the sum of a multitude of neural stimuli that will be elaborated by the sensibility of every one of us. When I create a new piece of work or a body of work, I don’t think about wearability and its functional role in the jewel at the beginning. That comes in the second stage—ideating is followed by the design development, which is equally important.

Have you noticed any changes in your recent practice?

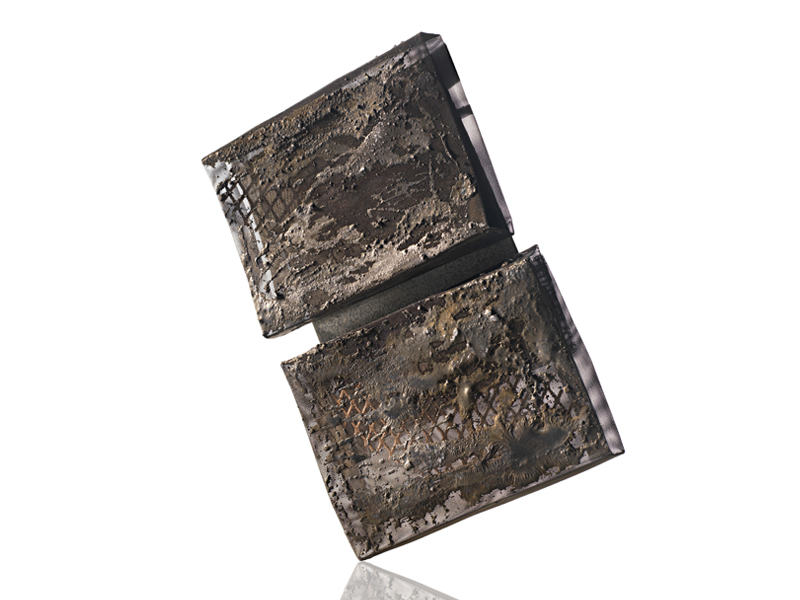

Annamaria Zanella: In recent years I have loved creating pieces of work where the material has an indefinable identity … I love ambiguity and the interplay of materials: True or false? Precious or nonprecious? Iron that looks like gold, paper that looks like lapis lazuli, aluminum that looks like a sea sponge, pieces of broken glass that have the same light and brilliance as a precious stone.

Tell us about the developmental process—its key stages and protagonists.

Annamaria Zanella: Every piece follows a different design process, even if for each one the beginning is always linked with a drawing, a sketch, or a sentence on a piece of white paper. Then I start to consider various materials that might be useful, and at the end I consider the functional part, its movement, I verify the weight, the dimensions, and so on. Sometimes the experimentation with materials makes me proceed backward, that is to say, it is the material itself (burnt wood, rusty iron, broken glass, plastic) with a strong evocative power that takes me “toward” a new collection.

What role do memories play in your work?

Annamaria Zanella: Every work is the result of a set of reflections upon what constitutes part of my own immediate life and my past life. Every work of mine is unique—a one-off piece because it represents a page of my life. My artistic journey is determined by my memories. The material (metals, plastics, pigments, colors, wood, glass, oxides, etc.) is the “ink” with which I write my life story.

Could you tell us how the relationship between you as an artist and the wearer has changed over the course of your career?

Annamaria Zanella: There has been a change over the years, as I now concentrate on the fact that a piece of jewelry, which I feel growing inside me like a poem, should not weigh too much if worn. This is the pretext of my presentation of necklaces in plastic and metal for Schmuck 2015, where the theme is Lightness.

After many years looking for new impressions in poetry, I’ve recently found inspiration on the Lightness theme from the book Six Memos for the Next Millennium, by Italo Calvino. “Lightness” is one of the most important lectures he wrote at Harvard University in 1985, the year of his death. In it, he states that “…literature has an existential function, the search for lightness as a reaction to the weight of living.”

My recent ideas are a tribute to Calvino and his unforgettable work. I was totally fascinated by the project of creating works lightened by the weight of the “matter.” Pieces made with the consistency of a poem. The substance remains, removing the superfluous. In the case of a poet, all the forces are spent on finding a perfect balance with words; a poet translates emotions into words. My intention is to give form, color, and functionality to a jewel by using the lightest materials (wood, plastic, aluminum, enamel, pigment). The “tube” in plastic is the theme that connects all the pieces.

You’ve said that the jewel has to be measured and created in relation to the human body. Do you actually have direct contact with your patrons or clients and create a bespoke piece of jewelry? Or do you have an ideal client for whom you design the object?

Annamaria Zanella: In recent years I never think of who might wear my work or about an ideal client. At a creative level, I would be stuck. There are already thousands of designers and makers in the whole world who do this kind of research with brilliant results.

How have audiences reacted to the provocative pieces in the series Boats from Africa? Do they feel they still want to wear the piece of jewelry?

Annamaria Zanella: They are not really pieces of jewelry to be worn … pieces like Boats from Africa or Burqa or Shoes (a brooch that talks about my disease, MS) are for collections. The provocation also lies in creating nonwearable pieces. For example, if you were to wear Boats from Africa for a minute, you would likely feel so emotional that you might feel the urge to remove the necklace from your body. I’ve seen friends cry just by holding the piece in their hands. There are strong vibrations in these works. Pieces of jewelry that have intense concepts spontaneously induce sensitive people to be moved and to interpret the work without feeling the necessity to wear it.

A provocative piece of jewelry does not need to have any reference to the function of decorating the body as it becomes a “concept” and receives a more respectful approach from the viewer.

How do you see the role of galleries and other agents in the act of disseminating your message?

Annamaria Zanella: The message is perceived when the work is showed with care in a gallery or museum. Or when it’s considered by a specialized magazine which disseminates the image and the critical text. An artist exists between solitude, silence, pain, fears, fragility, insecurity, emptiness, shadows, and contrary states such as joy, music, lights, colors, exuberance, power, passion, onrush, and certainties. This conflict of emotions generates the creation of the piece of jewelry as a work of art.

Jewelry becomes a microcosm of emotions. These microcosms need to be exhibited in appropriate spaces … that might even be inside a house, not only in museums or galleries. Like every work of art, jewelry should have a place of conservation and care. I’m so happy when I read that collectors who have collected contemporary jewelry with a lot of care and love for years then donate their collections to museums. They’re exceptional and generous people who make the artists and their pieces testimonials of jewelry art in our time and in history.

Have you ever considered working collaboratively for a jewelry project?

Annamaria Zanella: No. I’m against this because my intention is to create one-off pieces and make them with my own hands.

What do you wish for the jewelry field in the future?

Annamaria Zanella: More attention from mass media and art magazines in Italy. In Italy, there aren’t many spaces dedicated to contemporary jewelry and its research. It’s a neglected type of artistic expression, or only destined for an elite. I would like it to be understood and loved more, but this is a utopia. Beforehand, we need to educate the audience. Unfortunately, at present, interest from the vast majority of the public is minimal.

What advice would you give to students entering the world of jewelry?

Annamaria Zanella: I advise students to learn to “think” and develop personal research. The goldsmithing technique can be learned at any age and it’s a way to manifest an idea. However, beyond skills there must be a mature personality who knows his or her intellectual capacities and techniques for communicating emotions. There’s the need for a school that teaches to “think,” especially in the first years. In Europe and in other countries, there are schools and academies with jewelry departments of great prestige and very good teachers. Students need to try, try, and try without losing trust in themselves and their ideas. Work and learning always repay.

Could you tell us about you receiving a visit from the AJF group?

Annamaria Zanella: It was deeply emotional for me and my husband, Renzo Pasquale, from a human and artistic point of view. For their visit, I produced a video with images of my pieces of work in relation to images of places, objects, or book covers that inspired the creation of every work. I believe that everyone was struck and fascinated by this video. My photography has a universal language that goes beyond the limits of verbal communication.

To what extent have you been influenced or affected by discussing your work with the AJF group?

Annamaria Zanella: It was interesting to confront myself with various people who belong to the group—answering their intelligent and interesting questions. Those have been moments of considerable inner excitement for me. It’s like being naked in front of strangers, because you need to explain not only the technical aspects of your work, but also the spiritual side to your research. It will remain an indelible memory of joy and positive emotions. In the near future, I would like to create a piece of work dedicated to this visit in order to fix it in my diary of creations—this emotion and page of my life.

Thank you.

[1] Roberta Bernabei, Contemporary Jewellers: Interviews with European Artists (Oxford: Berg, 2011), 220.