Olivia Shih: After earning a BFA and an MFA in the US, you traveled across the ocean to an artist residency at the Estonian Academy of Arts in Tallinn, Estonia. What prompted you to take the leap? How has the experience influenced your work?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: The answer to why I leapt is convoluted and starts with divulging I’ve leapt before using different muscles. In the time between my concept of home became a scattered plural. So, should I pretend that my connection to Estonia is merely professional, as platonically cool as the Läänemeri lapping the shores of Haapsalu in late summer? At one point it may have been so, but simple seldom stays.

I have to snake back to 2011 when I had work included in Talente and traveled to Munich thanks to a crowdfunding project. During the blitzkrieg of “experiencing” work during those mad days I saw much, but little had true lingering power. One such exhibition was Tanel Veenre’s Paradise Regained. Staged within a historic building material shop, the work hung from slumbering wrought iron gates and ornate wooden doors waiting to be reclaimed and live again. And wasn’t that like jewelry too, waiting for the body? Later, Tanel graciously answered some questions on how the exhibition came to be, but I was still curious.

At the time, Estonia was a fuzzy somewhere at best, this placeless place. Now that I had this map pin of an experience, though, it became magnetic. An interrelated pattern emerged as I realized there were many Estonian jewelers whose work I admired but had been ignorantly blind of a shared origin. With a more defined understanding I saw a type of reverence; a way of thinking, feeling, touching, and speaking through consideration that tangibly connected object and maker. This work didn’t look like my work, nor work I would make, but I did identify with it in some way.

That same year I began my master’s studies at Cranbrook Academy of Art, and the work of Estonian jewelers sporadically found its way into conversation or became a point of reference in critique. Studying under Iris Eichenberg, there is an expectation to make the most of the break between years in order to carry and build the momentum into the second year. I had settled into the idea of spending my summer in Munich when very late one night, while I was alone in the studio, I think around one o’clock, the phone rang. On the other end was Iris and in a very succinct manner she told me Munich would be too easy, that I should follow my interest and see Tallinn for myself.

I sought advice from the only Estonian I knew in the slightest way. Tanel put me in contact with the jewelers of studio Gram, who maintain a collective space and are involved in a range of activities. The end result was two months living in Tallinn and a spot in Gram while one member was away. I can’t get into all aspects of the time spent there, the introspective nature of isolation, discovery of new interests, trying to source material, the insatiable appetite for juusturullid, and so on. But halfway through my stay things get complicated; it’s when I meet a stranger that the story turns from a pilgrimage in search of foreign jewels to how I met my husband.

There were loose ends, much of my curiosity laid with the Eesti Kunstiakadeemia (Estonian Academy of Arts) as wellspring of Estonian jewelers. I wanted to get a sense of the culture and pedagogy that was shaping how the jewelers looked out upon the world. I was there, though, during the summer, while classes are on break. So that second bigger leap, I stayed half a year in Estonia, and half of that as artist-in-residence at the academy. Of course, going back was a different creature, having in a sense been married to Estonia. It might seem like I paint a golden picture, but I must mention at this point my husband had moved to a third country for work and this more intense stay went into dark Estonian winter. So the theme of isolation deepens and the sense of searching for identity widens as the need to communicate compounds. There is no border between my studio practice and personal life; the real answer is not in how it influenced my work, but what change it had on life.

Could you describe a day in the studio for you?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: First thing that happens each day in the studio is I wake up. Most likely one of my cats, Elwood, is tracing some ghost of a reflection across the wall. I know they bounce off cars passing four stories below, but I can’t see them. I shush her chatters and swing my legs to the bed’s edge, sitting up. This aligns me perfectly with my worktable, bench pin leaning toward my chest. Thankfully, this early in the morning, there is still a yard’s worth of separation between us.

It’s hard for me to place a boundary on what constitutes my studio. When I look out the window and imagine the lives of the people waiting at the crosswalk and where they’re going … is that still my studio? Or how about when I run to the bodega to get milk for my coffee? My Spanish is just good enough to understand the cashier refuse to let a woman use the bathroom because her baby is asleep in the sink. A minute later I’m home and still imagining this water-basin bassinet and the baby, who I know as this wiggly boy on a hip, always grasping at something. He grabbed me once, too, while my hand was held out anticipating change. Then I remember I still owe her 50 cents from being short on cash buying cat food last week. By the time the milk splashes into my coffee, it feels borrowed. Did I mention my cats also sleep in the bathroom sink?

In many ways I feel the ideation of a creative practice around a physical space is anachronistic. When I create virtual objects on a computer, is the desk my studio, or is it just what is contained in the monitor’s frame, like the four walls of a room? Is it just the tools and limitations of whatever program I happen to be using? To confine a virtual practice to the computer is as irrational as confining a “real” practice to a studio.

Or is it just the place in my head where all my work comes from? Now that’s something I’d like to have a boundary to, to be able to step out of, but it’s not something I know how to do. My husband once asked me in relation to my work: “Is it good for you?” He wasn’t asking if all my efforts gain recognition, nor if it leads to success, but if it is a healthy thing. Not only physically, but also mentally. How much can one call and bleed into darkness, what is returned? So, how do I describe a day in my studio? Troubled.

The title of your exhibition, mirror milk, pulls together two everyday objects into an instantly memorable but unfamiliar phrase. Your work often explores the human need to define the self, a need that can be gratified or be exacerbated by mirrors, but how does milk fit into the equation?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: Mirrors offer a false truth; familiarity is a lie. As for milk, it is a wholesome opaque thing that easily turns sour. In society we are surrounded by “milks,” purported wholesomenesses we suckle from, foregoing culture as nourishment, but must be weaned from to survive. Subsisting on only the past is too rich a diet, we need to seek and consume unrefined solids from the untamed corners of our present to prepare for the future.

Parallels can be drawn to Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalytical concept of the “mirror stage” of development, particularly his later movement away from a specific period of development of the self, to playing a constant role in subjectivity. This further unfolds with Lacan’s orders of the imaginary, symbolic, and real; if it interests you.

The title also references a theoretical quandary within Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. Therein Alice speculates about the world in the mirror, how it differs from reality, and whether things that are safe in the real world could be harmful in the mirror. (Specifically within the text “Looking-glass milk.”) For this work, the mirror world is our self-perception within society. I’m trying to find for myself where the power and control lies, in casting a reflection there or being deceived by it. Norms are fluid, and only once you hold something for yourself do you realize how well you misunderstood the idea of it.

Your studio practice involves manipulating repurposed materials into an original visual language, where all trace of the original material is wiped clean. What draws you to repurposing materials and your specific treatment of these materials?

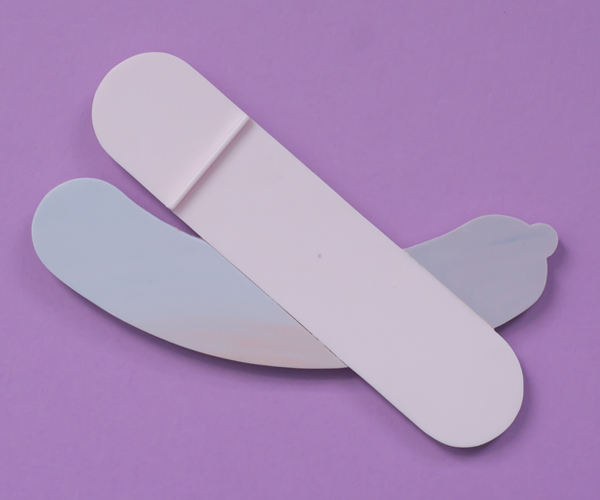

Timothy Veske-McMahon: I don’t view them as completely clean, more that I’ve been very selective about what information they are sullied by. I do think that I’ve in some ways deboned the original objects by removing any defining sense of form or original intended use. The raised lines crossing the surfaces originally channeled the injected plastic throughout the mold and remain authentic artifacts of their slight structure. It is clear to me that not much care was taken in their previous fabrication. This lack of scrutiny is glaringly obvious in the inconsistency of color. Pigments seem haphazardly added, bleeding into one another and creating muted tints that slowly build toward the mildly unpleasant. I find it especially suspect when one considers these were meant to be children’s paint palettes. They appear aged or perhaps sun-worn, but I have no knowledge of their true origin, even if I personally harbor some darkly romantic notions.

In this way I preserve some of the material’s culture for those who look for it: how it came into existence, how it was considered in handling, and that it once served a purpose. Otherwise, it’s just plastic. Alternatively, when I create virtual objects I am in a sense inventing material. As sterile 3D prints they begin blanched of culture. Here I’m not repurposing material, but images, patterns, and techniques in pursuit of authorship.

Many of your pieces in the collection pair together two shapes, two colors, two symbols. Is there significance in the number two?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: It’s the right amount of complication, one that doesn’t curtail possibility by implying too much. I try to balance these glyphs between being symbols and true logograms that one would assume had a “correct” reading. In the instances where I do incorporate more glyphs, it is to an extreme where they compound to a bewildered state. They crackle where the simpler objects buzz. I do regard these pieces as discrete lexicons, a completeness, from which nothing else exists in isolation. The personal “inspirations” come from decisions, possibilities, balances, etc., which we often grasp in binary. The come from very real concrete thoughts, issues, or feelings, but that isn’t important once my eyes leave them. I feel that I have imparted a loudness with even only two glyphs, and I don’t want to be apologetic. There is no linear narrative; I set the tone but meaning comes repeatedly anew in the object’s afterlife. I’m much more interested in how others project meaning from their own life onto them than correctly identifying what anxiety I was suffering that week.

This collection of new work is imbued in a palette of cool pastels, creating an aftertaste of loss. The graphic lexicon, which references hieroglyphs and symbols but is ultimately unreadable, enhances the sense of loss with alienation. How did loss find its way into your work?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: Loss of place, loss of words, loss of understanding, loss of purpose, loss of self. While in Estonia I was at a tangle of life events. Fresh out of master’s studies and trying to reenter and redefine a professional practice. Newly wedded, a proposal that just a year earlier would seem laughable. What was this life around me? Is this adulthood? What is a marriage? How long in lasting? Where should I be? It’s when I most need to clarify what I want in life that I begin to come up short in understanding who I am. In the moment, it is a tremendous loss.

Could you name three emerging artists who have introduced a fresh perspective to art jewelry?

Timothy Veshe-McMahon: I know this is only a dwarf pulpit, but forgive me for co-opting the question nonetheless. I think the use of the word “emerging,” and the stratification it represents, is unethical. We have an oblique system of consideration for objects based on how we conceive artists, which remains true when inversed. At one point the terminology of emergence was more appropriate, when an artist gradually emerged because they earned, through various discerning bodies, opportunities that granted increasing levels of exposure. Here recognition is coupled with worthiness. In today’s hyperconnected world, though, we have a competing mechanism of cognizance-as-relevance where artists use social media to self-emerge whenever they see fit and without discernment. At this time it isn’t uncommon for graduate students to post, tweet, and/or stream every step of their master’s studies.

Are we ok with that? Shouldn’t these objects be saving their performance for critique, and not spending it on likes and shares? Is an investigation that is aware of its own performance actually research? Not only is this a disservice to what we expect from an undertaking of master’s study, but it places work created under mentorship out of context and offers it up to receive recognition as product of a professional practice. In comparison, what happens then to the artist who doesn’t feel that social media has a place in their artistic practice?

So if we want to continue using the terminology of emergence, we need to define what we actually mean, and by extension understand what it means to have a submerged practice.

Are we talking about success, potential, recognition, representation, collections, something as arbitrary as time? We need to stop caring about and rewarding something as anachronistic as a singular emergence, and start commending artists of all ages and levels of success for how much risk they take, rather than for their consistency. Their future potential for expanding the field is much more important than how well they succeed. We need to pinpoint art that is in danger of being unwillfully submerged.

We have this incredible push toward entrepreneurial ideals, which I see as supplanting experimental work. What honor is there as an artist to emerge within a system that favors precious over precocious? I think in most cases what is currently referenced as emerging artist would be much more accurately referred to as “emerging product.” Maybe it’s just that I’m searching in life for meaning, but I want to make and see things that matter. Being well made, aesthetically considered, or popular does not remedy meaninglessness.

Where is the necessary differentiation that allows conceptual jewelry artists to prosper? Why are there so many multi-juror selection processes when all they do is quicken the homogenization of the field? The premise that work must be “good enough” for all jurors, that work that is good to only a minority is not “reliably good,” is flawed. Truly deserving artists are more likely recognized through contention rather than consensus. Our most common systems of recognition only ensure that true revolutionary work is rarely selected. Extraordinary work requires extraordinary perspective to recognize it. It is actually the “good” work that is discerning of a good juror and not the other way around.

Internally, we need to stop tending to objects and start supporting artists. Museums, collectors, curators, jurors, galleries, and organizations have to start allocating their resources where their mouths are in terms of contemporary jewelry having relevance. We need more non-commercial exhibition spaces and opportunities that aren’t tied to traditional craft institutions with the associated agenda. We need work that isn’t so easily packaged, work that isn’t so coyly aware of its salability.

So, who are three artists making important work that should be more widely discussed?

I’ve known Leslie Boyd since her time as an undergrad student at Pratt Institute, but she went on to do her master’s at RISD and created her series My Favorite F-Words; Family, Freedom, Feminism, Fucking. The work explores gender, class, pop culture, feminism, and sexuality through object-making, self-portraiture, and installation. There was no compromise, no middle ground of pleasantness or easily discrete objects. Thinking realistically, where does this type of work currently live outside of academia? Who is invested in supporting the practice of jeweler-artists who push us collectively toward social relevance without capitulating to a preciousness that remains appropriate hung over a mantelpiece? Someone should approach Leslie with an opportunity, or better yet, an offer to bankroll new work.

I don’t know Zachery Lechtenberg personally, but I’ve seen his cartoon- and comic-inspired enamel brooches pop up periodically over the last couple years and have been keeping an eye on them. Here’s the thing, though; what excites me is the potential for his subject matter and style to be social commentary and because of my distance from it, I don’t know the intention. So right now I still see the work forking two ways, as quirky products as an extension of his personally branded world, or as part of an extroverted conceptual practice that assimilates and reflects issues of the real world.

Saving the most seemingly nepotistic for last, Alissa Lamarre and I attended Cranbrook together, but trust me, she deserves recognition. It’s hard to use the word authentic without it seeming somewhat diluted, but it is the best descriptor for the consideration Alissa has for her work and the place it comes from. Alissa is a smooth shifter, moving easily between jewelry and object making as she imparts a strength of being and a self-aware sense of wayfinding in her work that approaches us like a quietly patient outstretched hand.

Have you heard, seen, or read anything of interest lately?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: I picked up a book on sincerity from a used book shop; it has been dutifully filling the role of subway and park bench reading. It’s entertaining. The author is R. Jay Magill, Jr., and the full title summarizes it well: Sincerity: How a moral ideal born five hundred years ago inspired religious wars, modern art, hipster chic, and the curious notion that we all have something to say (no matter how dull).

Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, by David Blazer, is another book I read recently that I would recommend, but especially to those who have toiling thoughts on how work gets shown. It stretched my perspective back much further and rewrote basic principles of how I see a curator. It’s a book that can help give direction and form to those unsatisfactions you may be feeling, if you know what I mean.

If you come to NYC this summer, make sure to visit America Is Hard to See at the Whitney.