Susan Cummins: Did you discover you were a jeweler while you were attending Rhode Island School of Design, or did you know before that? Please tell the story of how you became a jeweler. Did you grow up on the east coast? Where?

Valerie Mitchell: I was born in Hollywood, California, where my dad Victor was shop foreman at the established Allan Adler Silversmiths. At age six, we moved east by train, and I grew up in Bristol, Connecticut. My genetic influence was increased by the curiosity of odd jewelry parts, stones, and hand tools stored in an old workbench in our basement my dad infrequently used. My first jewelry lesson was the summer after receiving my BFA, followed by other area workshops. In 1977, I moved to the Hartford, Connecticut art community, where I developed as an artist, utilizing jewelry as a sculptural, wearable expression while a member of Artworks Gallery. I had a one-person show titled Jewelry from my Environment at the nonprofit downtown space and also a four-person exhibition called City Limits of work inspired by visuals from my urban environ at the Old State House Gallery. My training was minimal but my artistic energy strong. Five years later, I decided to be serious about my training as an artist and craftsperson and chose RISD and Providence for my MFA in light metals.

Susan Cummins: Did you discover you were a jeweler while you were attending Rhode Island School of Design, or did you know before that? Please tell the story of how you became a jeweler. Did you grow up on the east coast? Where?

Valerie Mitchell: I was born in Hollywood, California, where my dad Victor was shop foreman at the established Allan Adler Silversmiths. At age six, we moved east by train, and I grew up in Bristol, Connecticut. My genetic influence was increased by the curiosity of odd jewelry parts, stones, and hand tools stored in an old workbench in our basement my dad infrequently used. My first jewelry lesson was the summer after receiving my BFA, followed by other area workshops. In 1977, I moved to the Hartford, Connecticut art community, where I developed as an artist, utilizing jewelry as a sculptural, wearable expression while a member of Artworks Gallery. I had a one-person show titled Jewelry from my Environment at the nonprofit downtown space and also a four-person exhibition called City Limits of work inspired by visuals from my urban environ at the Old State House Gallery. My training was minimal but my artistic energy strong. Five years later, I decided to be serious about my training as an artist and craftsperson and chose RISD and Providence for my MFA in light metals.

After high school, I attended The Rochester Institute of Technology, and after freshman foundation, decided that I would enter into the metals program. However, after two years, I felt the program lacked conceptual expression and ultimately dropped out. I received an offer to work for a goldsmith in Worcester, Massachusetts. I moved, and in addition to working, I started researching other programs that might be a better fit for me. One year later, I transferred to The Rhode Island School of Design to finish my undergraduate training. In retrospect, I feel the combination of the two schools was highly complimentary and has influenced my work greatly.

I was born in Oil City, Pennsylvania, during my father’s orthodontics residency. My father wanted to settle somewhere where our family would be able to sail in the summer and ski in the winter. When I was two-years- old, my parents and my three brothers moved to Erie, Pennsylvania.

This show is called 30 Years West. I understand that after graduation you both drove to the west coast together. Why?

Sandra Enterline: It’s a little sad to admit, but it involved men for both of us. I was heading to San Francisco to continue a relationship that began at RISD with my husband David Walker. Val was heading out to Los Angeles to reconnect with Tim, her longtime boyfriend. We drove across the country in a borrowed car. Val’s cat Bird Dog was our dashboard ornament. Of course, the car broke down along the way only adding to the adventure.

The most memorable experience on our journey was at the worst hotel EVER in Salt Lake City. The hotel was a men’s hook-up hotel. It was listed in Let’s Go USA! We were too exhausted to switch places. Even the concierge greeted us from behind a “Mr. Ed” door. I don’t think he had much on below, clothing wise. I slept like a board that night for fear of touching ANYTHING. Ultimately, the trip was a tremendous bonding experience.

Valerie Mitchell: (We drove west … ) To test the waters of our potential life partners, who became the loves of our lives. I was rejoining an earlier relationship that moved cross-country on a BMW motorcycle to Los Angeles. I wanted to experience an artistic and creative environment different than the conventional east coast. To reconnect with formative years and memories of a geographic land different than all the explored regions of the east was calling me. Sandra and I shared a studio at RISD together, and after graduation, we did our first ACC craft market in Springfield, Massachusetts. I came back to a burnt-out apartment building and a missing cat, with the Talking Heads record “Burning Down the House” melted on the record player—seriously. Sandra and I shared our first market, a studio, and spent the summer filling orders from the show. I was newly graduated without a home, so my west coast interest Tim thought it was a sign—time to leave and move to Los Angeles.

Although you both attended the same school, your work looks very different. How do you think your RISD education shaped you?

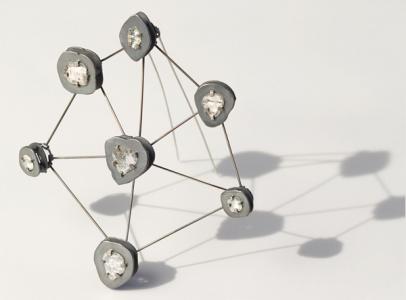

Valerie Mitchell: RISD shaped my aesthetic for the minimal and conceptual, helping me find my own voice and to learn the craft and development of ideas. I went from interpreting my “environment” to personal iconography. Exposure to sculptural form, drawing, and filmmaking was a plus. The study with artist-in-residence Michael Glancey introduced me to electroforming as a unique process for my visual vocabulary. RISD exposed us to another world of jewelry artists, especially focused on European jewelers. Recently, I was granted a large public commission to create 54 medallions on light poles marking our arts district. I think of it as jewelry for the city, which was an interest of mine before attending RISD. As designer and contractor, I found myself relying on the skills I was introduced to in navigating the challenges of material and production. I approach my college design teaching with RISD in mind.

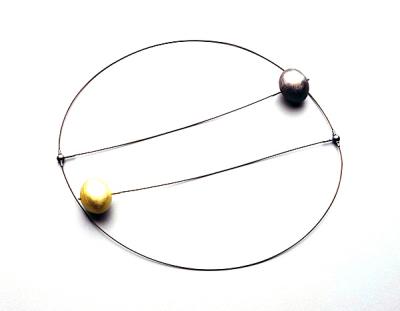

Sandra Enterline: RISD nurtures students to develop their individual voice and aesthetic vocabulary. Val was a graduate student and I was an undergraduate student, so we were involved in very different programs. In the undergrad program, there was a rigorous emphasis on design, concept, and technical mastery. I took as many sculpture courses as possible, which resulted in my senior project focusing on jewelry and sculpture. It included carved plaster objects that were electroformed and patinated. I used the connection that was attached to the anode as the post that could be slid into the wall. They were displayed at varying heights though out the gallery. In addition, I exhibited sculptures made from plaster-covered Styrofoam, plaster-filled balloons, tree branches, and an abundance of nails and spikes. My jewelry work was a hollow construct and minimal, aimed at echoing the other forms I was creating but on a smaller scale.

Valerie, how would you describe Sandra’s work, and Sandra how would you describe Valerie’s work?

Sandra Enterline: Valerie’s work has a strong sense of the hand in it, especially the electroformed work. It is very tactile and sculptural work accentuated in the way you can see her fingerprints hinting how the wax was manipulated. There is a strong connection to the natural world—seedpods, tree branches, and capsules. You can feel life emanating from the work, although not literal translations. There is an ease to the pieces that is not awkward or mannered. Certain works feel as though they were effortless to make.

Valerie Mitchell: Sandra’s work is cool, minimal, deep and reflective, exceptionally crafted, very defined, and emotionally intriguing. Her work is conceptually exquisite and brilliantly executed. It shows a purity of form and secret, special places. It holds space dearly. Her determination on drilling all the holes instead of working with a laser speaks to the concern for applying detail that respects the shape to which it is applied.

Valerie Mitchell: Gravy … with a little stuffing … sides that, being opposites but with aesthetic similarity, and inspiration in form and nature, and a love of each other. A similar trigger in shape and form found in nature inspires us, but we approach and design from opposite corners. This inspires the motivation that occurs between artists and the spark that shows our differences.

For example, we were both inspired by the double cell circle form on new work while not aware of the other’s interest. You can see that in Sandra’s brooch with two circle forms joined in the middle. At the same time, I was working that shape in my cell division work in cement and silver. Our inspiration from organic and geometric structure is mutual, as well as our respect for influential German jeweler Hermann Jünger.

In addition to many memorable holidays together, snow bound in Tahoe or climbing the dunes in Point Reyes, Sandra and I also worked together on projects. We collaborated on a multiple-ring concept for Perimeter Gallery in Chicago, taught workshops at Mendocino Art Center, and roomed together at the major, stressful fine-craft shows, such as Smithsonian, Philadelphia Museum, and ACC Baltimore. We adapted and learned more about each other through the challenges of our work, passion, and private lives.

Many shared holidays and adventures have formed a lasting bond. Meeting up in Joshua Tree, Lake Tahoe, and Mendocino have helped us keep in contact. We have made extensive road trips to Ridgecrest, California, where Val and Tim own 5 acres of magical desert landscape. We cook, talk about our work, walk, ride mountain bikes, and take in the beauty of the Owens Valley.

What have you seen, heard, or read recently that has been stimulating and worth passing along?

Valerie Mitchell: The California Design Museum exhibit at LACMA last year showed historical works of art, craft, and design. I was so inspired by work I had never seen before, from the 1940–60s, and I saw strong relationships to my work. While I watch little TV, I love the new series Cosmos. It opens so many doors and is truly imaginative. The 2013 SNAG Conference in Toronto, with all of the great exhibits, showed the strength of our medium as artistry. Living in the arts district creates exposure to the unexpected. At Southern California Institute of Architecture, or SCI-Arc, lectures and exhibits organized by international groundbreakers in urban form, planning, and architecture are exciting. I also love how the structure found in nature is manifesting itself in the manipulation of contemporary industrial form.

Life has come full circle by embracing what you know to move forward. In the wonderful travelling museum exhibition Craft in America, this thought was illustrated. My Fourth Street Bridge tiara was placed next to Allan Adler’s Tiara for Miss Universe, which was most likely created at the time my dad was shop foreman there and just when I was born.

Sandra Enterline: I am very impressed by the work of Tokyo-born architect Shigeru Ban, who recently won the 2014 Pritzker Prize. For 20 years, he has traveled the world and helped communities rebuild after natural and man-made disasters. He works with students, local citizens, and volunteers to design and construct low-cost shelters made out of recyclable materials.

One of the signature materials he employs is recycled cardboard tubes. He uses them for columns, walls, and beams because they are readily available, inexpensive, lightweight, strong, and easy to transport. His Japanese upbringing accounts for his wish to not waste materials, he says.

Not only is his work interesting to me because of its intelligent use of recycled material, but his work is also sublime, elegant, and extremely inventive. My oldest son is currently studying architecture, and it is my hope that a new generation of architects will be influenced by such work.