To Speak with a Golden Voice

July 16, 2020–April 11, 2021

Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art, Vancouver, Canada

“One basic quality unites all of the works of mankind that speak to us in human, recognizable voices across the barriers to time, culture, and space: the simple quality of being well made.” —Bill Reid

The exhibition To Speak with a Golden Voice, at Bill Reid Gallery, in Vancouver, celebrates the centennial birthday of Bill Reid (1920–1998).

Reid lived among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. He learned from both; he created art in both. He had a life-long dedication to making well-made work, which was highly valued in both communities.

The Bill Reid Gallery doesn’t look like many other galleries. There is no white cube, the now nearly ubiquitous art world style of minimalist white walls with a few art objects carefully positioned around the room. Rather, at Bill Reid Gallery, the walls and room are full of the diverse work and words of Reid and the many people who learned from and worked with him. The space is welcoming. In this non-intimidating environment, visitors feel encouraged to explore and learn. The gallery, like Reid himself, builds bridges between communities, including Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, through the presentation and education of Reid’s life and work, as well as other contemporary Indigenous Northwest Coast Art on which his work has had a significant impact.

Reid carved massive poles from wood and tiny pieces of jewelry from gold. The wide range of his work, including his writings, prints and sketches, and wall hangings and wire sculptures, are part of the exhibit. But Reid started out as a maker by making jewelry, and his love for this art form continued throughout his career. Later in life, looking back and forward, he said, “I have a feeling that I’ve really done enough large wood carving. If I couldn’t do anymore, I wouldn’t regret it very particularly. But if somebody said I couldn’t make any more gold jewelry, I would really feel pretty upset about it.”

As you walk into the gallery, toward the right side stand the cases displaying the jewelry included in the exhibit. The display cases sit mounted within wooden poles that rise from floor to ceiling.

As a jeweler, Reid was trained by traditional Haida carvers and by master European goldsmiths. He made contemporary jewelry and traditional Haida pieces. Eventually, he merged both, creating something new. Reid brought repoussé and hinges to Northwest Coast Indigenous art, and he brought Haida thinking to modernist pieces. As Reid, quoted on cards sitting next to his jewelry in the display cases, explained:

“I started out with the desire to become the great contemporary jeweler, but I got sidetracked, and I’ve done mostly Haida style carving and jewelry making.”

“… my interest in Haida art gained more stimulus, and I began to devote all my creative activities to applying the European techniques I had learned to an expanded application of the old Haida designs in jewelry.”

“One day I did something different, something that didn’t relate to the old design, and I realized that I could do different interpretations of the old forms.”

The variety of jewelry chosen for the exhibit demonstrates the range of Reid’s work coming from the presence and blending of his different communities. One display case includes contemporary pieces of gold and diamonds; the next, traditional Haida designs in large cuffs. At times, these contrasting styles are right next to each other in the same case or even within the same piece. Seeing such disparate styles by one artist in one exhibit is unusual; it almost appears to be the work of many artists rather than one. But this atypical approach shows Reid’s vast and varied knowledge, experience, and talent. It is a powerful way to highlight the key themes of the exhibit: Bill Reid’s voice, process, lineage, and legacy. Below are some examples of the multiple worlds and influences that comprise the jewelry in the exhibit and Reid’s work and life:

Reid made his Milky Way wire and pyramid necklace of white and yellow gold and diamonds, with a removable brooch, during his time at the Central School of Art and Design, in London,[1] when he was in his late 40s. As noted in the exhibit, the piece at first doesn’t appear to have a Haida connection. However, in the piece, Reid was working with the Haida practice of using two concepts in one space, at one time. And the pyramids throughout the piece represent the smoke hole of Haida longhouses, “where souls enter and leave at birth and death” and “how Raven escaped to deliver the moon and stars to humans.”

During a trip to the Louvre while visiting Europe, Reid spent hours closely examining Fabergé’s work, focused on the well-made hinges. Describing what he saw at the museum, Reid half jokingly said that, among the many holdings, he “saw a hinge.” In his Abacus hinged bracelet (with matching earrings and brooch) of sterling silver, ebony inlay, and coral beads, Reid fabricated award-winning wearable art from modernist artist John Koerner’s designs. In the Tschumos Bracelet, Reid adds hinges to Haida bracelets, which traditionally were made in the form of cuffs.

The gold Mythic Messengers bracelet is a replica of a bronze relief that Reid made for a Canadian telephone company, in which he depicted communication through the linked tongues of humans, animals, and mythical figures. Of this work, Reid said, “the power of these old forms, born of a mythological past, reinterpreted through new materials and techniques, in a contemporary setting, can still speak to us across time, space, and enormous cultural differences.” As others have noted, Reid was uniquely skilled in blending traditional stories with the present experience.

A ring of silver and abalone from the late 1940s is one of Reid’s earliest pieces. He likely made it when taking his first jewelry-making courses in Toronto while working nights as a radio broadcaster for the CBC. He had wanted to take a class in jewelry engraving but that class wasn’t offered. At the Institute of Technology, he learned European jewelry-making techniques. Not far away in the exhibit sits another one of his first pieces, the Bear of silver. Reid called the piece, “a very funny-looking bear, who didn’t bear any relationship to anything, Haida or otherwise.”

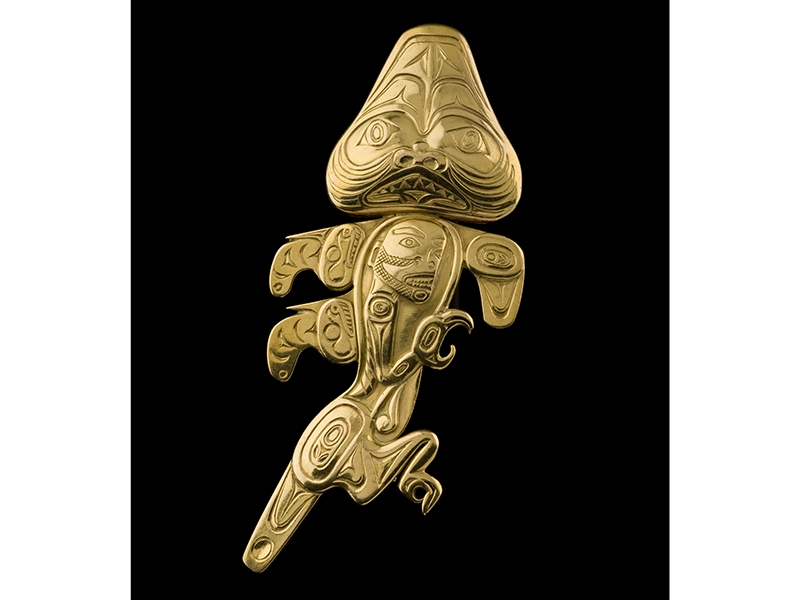

His Dogfish brooch of gold was inspired by the work of his great-uncle Charles Edenshaw. The dogfish design was originally in a drawing Edenshaw made of his wife’s tattoo. It was also carved in a gold bracelet that Reid purchased from an antique store in Toronto when he was in his 20s. He bought it although it was a stretch for him financially at the time, and at that point he and the store owner didn’t know it was Edenshaw’s work. But he knew he had to rescue it after passing the bracelet in the window every day and being reminded of the bracelets his mother wore.

Reid also developed his Killer Whale design, shown here in a brooch made of gold and abalone, from a tattoo drawing by Edenshaw. Some of the first killer whale designs he made were attached to triangle shapes to make earrings, straddling Indigenous and contemporary art. In the exhibit, his killer whale motif is found in a silver brooch (circa 1955), gold earrings (1971), and boxwood (1982). His Killer Whale design was also made into the massive bronze sculpture (executed in 1984) that today sits in front of the Vancouver Aquarium.

The Cavelti-Reid Bracelet is a final symbol of a mutually influential relationship between Swiss-Canadian jeweler Toni Cavelti and Reid. Cavelti finished it after Reid’s death, combining Reid’s gold bear masks with his own diamond and platinum details.

The Beaver bracelet of sterling silver is Reid’s last silver bracelet. As noted in the exhibit, one ovoid, a shape central in Haida design, remains unfinished.

Reid mastered the styles and techniques of different worlds. But for him, as with many members of Indigenous communities, it was not a free choice to know both worlds. Individuals who are not part of the communities who control the art world know their own communities, but they must also know, even if from the outside, the communities that control the opportunities. Reid’s mother, a survivor of the residential school system in Canada that operated to erase Indigenous art, language, and ways of life within Indigenous communities and replace them with European culture, did not openly identify with her Haida heritage. Yet Reid remembers her wearing Haida bracelets layered on her arm, a subtle but powerful way to maintain and pass on a connection to her Haida community. In an interview, Reid explained how his mother’s bracelets inspired him to take his first jewelry-making course: “I thought they might be able to teach me to make jewelry like my grandfather…had made for my mother…”

Reid had the opportunity to learn from traditional Haida artists, including his grandfather, Charles Gladstone, who had learned from his uncle, Charles Edenshaw. Reid inherited the engraving tools that were passed down this lineage. But that connection only happened later in his life, when he was in his 20s. Reid, in turn, passed this knowledge on to the next generation of jewelers after him. Gwaii Edenshaw, Reid’s last apprentice, is the curator of the exhibit, and his gold Stone Ribs pendant sits next to Reid’s Haida Beaver Pole as part of the show. In a talk about the exhibit, Gwaii Edenshaw shared how Reid’s studio always had an open door for him and the many other Haida and non-Haida artists with whom Reid shared his knowledge and talent.

Nonetheless, among the jewelry cases is a mask on one of the poles with gold on its lips that repeatedly plays Reid’s voice saying: “Shows how far I was removed from my Native heritage.” Although Reid was removed from his Haida community for much of his life, being Haida he had a wider, vaster knowledge than the non-Indigenous artists of European descent who operate solely in the dominant position in the art world. These reigning artists are able to, and often do, choose to ignore the work of those in less dominant positions. They can “succeed” by staying with what they know, ignoring and excluding artists in other communities and cultures. But what is often overlooked is that this limits knowledge, talent, and creativity. This limits art and the art world. Diversity, representation of many voices, provides new information and ideas. It brings new viewpoints, experiences, and ways of doing things. It expands the monotonous white walls of galleries. It brings us together, as Reid said, through the “quality of being well made.”

Thank you to all of the sources of information I relied on to learn about Bill Reid’s life and work for this review, including:

Bill Reid Foundation, including talks sponsored by Simon Fraser University

Bill Reid Gallery

Bill Reid, dir. Jack Long (1979, National Film Board of Canada), documentary.[2]

Doris Shadbolt, Bill Reid (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2003).

Maria Tippett, Bill Reid: The Making of an Indian (Toronto: Vintage Books, 2003).

[1] The institution later merged with Saint Martin’s School of Art to form Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design.