ISBN: 9780764353383

Cast: Art and Objects Made Using Humanity’s Most Transformational Process, the book by Jen Townsend and Renée Zettle-Sterling, is an impressive achievement—not only through its sheer physical appearance, big and thick, with more than 400 pages, 800 images, hard cover with embossed title, and a weight of roughly 3 kilos, but also because of all the knowledge that is brought together, all the research that has been done.

Cast: Art and Objects Made Using Humanity’s Most Transformational Process, the book by Jen Townsend and Renée Zettle-Sterling, is an impressive achievement—not only through its sheer physical appearance, big and thick, with more than 400 pages, 800 images, hard cover with embossed title, and a weight of roughly 3 kilos, but also because of all the knowledge that is brought together, all the research that has been done.

Initially the two authors, both with a background in jewelry and metalsmithing, wanted to write a book about casting for jewelry, but as jewelry is not confined to metal alone and uses so many media, they decided to go deeper and extend the subject of the book to all cast media, fine and applied arts alike.

The book is imbued with an infectious love for the subject. Townsend and Zettle-Sterling start by showing the reader that our entire daily environment consists of cast things. As casting hygiene improved over time, food could be kept, traded, and preserved, and cities were built. Most building material is cast, as are our dinnerware, cups, bottles, toilet bowls, tiles, bathroom fixtures, flowerpots, plastic garden furniture, and so forth. These facts introduce the subject of casting as an indispensable endeavor, while at the same time drawing the attention to industry and mass production, which contradict the principles of applied arts. The authors signal an aversion to casting among their fellow craftspeople, and they find it regretful that casting is taught at most academic institutions as a necessary evil.

They see two reasons for this resentment: The first is the association of casting with industry and mass production, i.e. cheap, fast, anonymous, and ugly—industry as the nemesis of craft (costly, slow, individual, and aesthetic). Industrialization caused a protective attitude among craftspeople: the handmade became the ultimate guidepost. As a result, the apparent contradiction of machine made versus handmade still influences art education and practice even today. The book makes a plea for seeing the handmade and machine made as complementary to each other. The numerous examples support the mission of the authors. Of course, we can add that this view is not new. The emergence of new technology some 30 years ago invigorated the discussion about hand versus machine but—at least in jewelry—the struggle seems tough. A book like this has the potential to actually influence the discussion because it shows the astounding richness of applications of the casting process in an artistic practice in any conceivable medium.

The other reason for the low regard of casting is the adagio of the importance of the idea over the object that gained foothold in art in the 1950s and 60s and was soon adopted in the applied arts. As the authors write: “This value system has affected everything from the education of fine art students, art historians, and critics to what is studied, discussed, and written about in fine art journals and books.”[1] Technique has become a footnote, they write, and I would like to add: if only that were true, because generally technique is completely shrouded in mystery. Most artists are not very generous in sharing technical information voluntarily, and most art writers are completely ignorant. The writers of the book conclude: “If process is craft’s pride, it’s fine art’s dirty little secret.”[2] Head over hand, idea over object, the artist as a genius, and the immaculate conception of an artwork—I agree with the authors that it is time we let go of these ideas. For an artist such as Ai Weiwei, the material, history, skills, and division of labor in Jingdezhen porcelain industry was instrumental for conceptualizing and producing Sunflower Seeds (2010–2011). The artist disseminates the story of the conception of the artwork on the Internet.

The authors of Cast wanted to fill a gap in the available literature by making a book that covers all casting processes in any conceivable material—as a phenomenon that fosters cultures and the arts. The reader who is searching for a book about techniques will be disappointed—Cast is not about that. The book focuses on the history of the casting process and how it is applied nowadays, in different realms (metal, ceramics, glass, and jewelry), including “unconventional approaches.” Although this choice is explained in the introduction, the reader nevertheless misses technical information at certain points—luckily, there is a glossary.

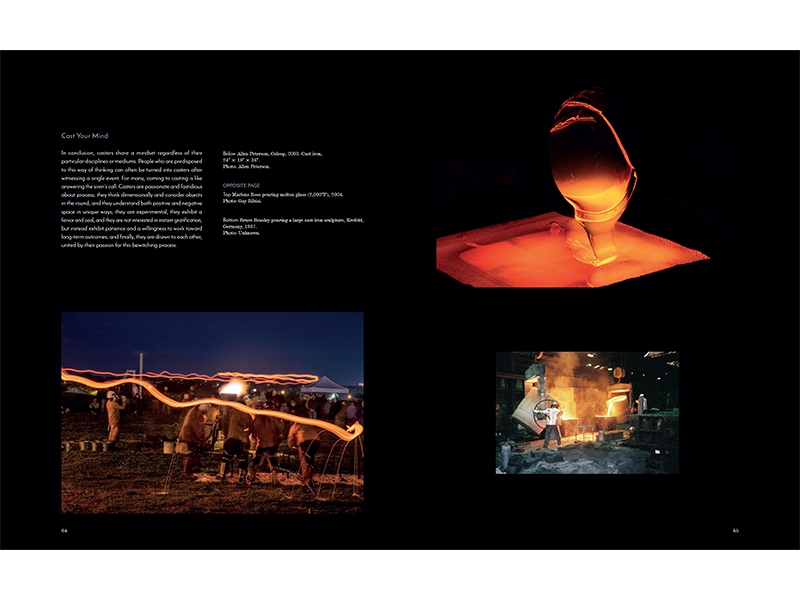

The sub-chapter The Mindset of Casters, part of the chapter Creation, sounds like an appealing subject. But unfortunately, it has been cut up into several short paragraphs lacking an integrated viewpoint. There are interesting starts, such as the notion that “casters think in the round,”[3] a captivating idea that isn’t carried any further. The paragraph with the heading Monomania[4] starts promisingly by telling readers that making molds or casts can become a sort of obsession, but contrary to the nature of the subject it ends abruptly after a few lines. The chapter ends by presenting casting as a group effort with a strange cult-like character, involving magicians who are drawn to the fire and drama of the cast itself. Reading about Allen Peterson’s cheerful midnight casting events and watching some videos of these happenings on the Internet made me aware of something essential not mentioned in the book: the fact that the connection between people and fire is pivotal in the evolution of mankind. And also that the first casters of metal, thousands of years ago, were probably viewed as wizards. The implications of making a fire, building a kiln, and being able to reach such high temperatures that metal would smelt, in conjunction with the symbolism and power of this act of alchemy, are not discussed in the book. To find such information, one has to turn to material culture studies, and research done by archaeologists and anthropologists.

Sometimes dates and knowledge are presented as unwavering truths. The writers introduce the oldest cast beads, made from lead, as being about 8,500 years old and found in graves in a place called Çatalhöyük (in present-day Turkey), without any reservation.[5] An author with a background in art history or archeology would mention the ongoing and fascinating research and academic discussion about these beads and metallurgy. According to the latest insights, the copper (not lead) fragments found in the graves were the result of an accidental fire, not of firing in a kiln, so melting instead of smelting. In conclusion, the history of metal casting began later than the book suggests. And so, obsolete knowledge is reproduced, and that is rather unfortunate for a book like this that wants to set a standard.

By inviting specialists to write about the history of casting in certain fields (metal, ceramics, glass), and about casting practices nowadays, the authors teach the reader a lot about the ups and downs and the meaning of casting in certain realms and time periods. In Suzanne Ramljak’s essay Mold Culture—Casting through Western Art History, we can read how the mold and casted reproductions in a way “molded” our Western understanding of aesthetics and perfection. Copying was instrumental from antiquity until well into the 20th century.

In the chapter Re-Renaissance, Joseph Becherer covers the subject of large-scale casting from Donatello, via Rodin, to modern and contemporary art—a history of alternating flows of sympathy and rejection. Although the writer sees a cohesion in the Western tradition up ’til now, he signals a growing critical impact from Chinese artists today on the world stage.

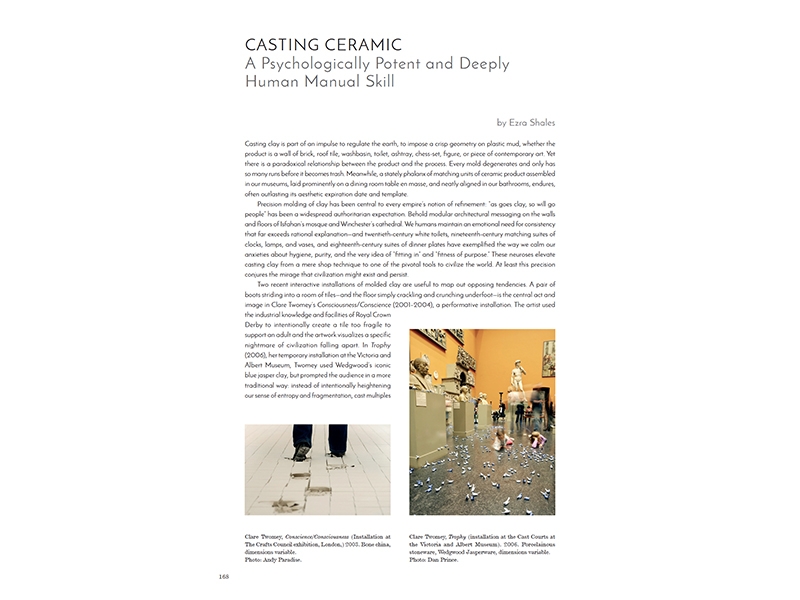

In his essay Casting Ceramic: A Psychologically Patent and Deeply Human Manual Skill, Ezra Shales writes about the importance of molds in industry and in the practice of contemporary ceramic artists. Shales fluently switches from the psychological need to regulate our surroundings, to bring order and “… impose a crisp geometry on plastic mud,”[6] to a novel interpretation of two projects by Clare Twomey which are based on the use of cast clay.

Shales sheds an interesting light on man’s affection for standardization and high finish, exemplified by the fact that most things people have an emotional bond with are machine made. He calls this love for a tactile and material sense of order found in mechanically made objects “technophilic.” The tone of his essay is critical, tackling many clichés by introducing new views: Casting is an age-old way of reproduction; there is an intertwinement of social developments (etiquette) and the implementation of casting in plaster molds to ensure the production of large-scale standardized tableware; Walter Benjamin’s “…and other characterizations of large-scale serial production as novel and inherently psychologically disruptive ought to be read with a grain of salt”[7]; the machine age changed little in the ceramic casting process; and there is still a lot of manual work in the ceramics industry. His excellent essay ends with descriptions of alternative ways of casting, developed in the past decades by artists, undermining the overdetermination of the mold.

Susie J. Silbert surveys the history of glass casting from Mesopotamia through today. Glass casting began some 5,000 years ago in the Middle East, as an art of imitating costly materials by fusing glass in molds—a tradition that continued in the Greek and early Roman cultures. Technical innovation led to improved kilns, resulting in the discovery of glass blowing some 2,000 years ago. Molds were used to create specific shapes. As is the case with metal casting, the technique of glass casting went dormant only to be rediscovered during the rule of King Louis XIV, who ordered the Hall of Mirrors for his palace in Versailles—the huge mirrors were made through hot casting technology.

In her chapter Unbounded in an Expanded Age, Elaine A. King presents an array of contemporary artists who use alternative casting methods that often have a dense metaphorical meaning within the context of a critical theoretical framework.

Thanks to these specialized chapters written by respected authors, Cast gains extra value. In every chapter you can read between the lines that there is so much more to tell about the subject, but nevertheless all the writers succeeded very well, providing interesting views and stories and leaving room for amazement and questions.

Some mysteries remain veiled. Take the question of why the lost wax technique practically went dormant after the Roman empire to be “discovered” again by Renaissance sculptor Donatello around 1440. A fact like this, presented by different authors in different chapters, leads to questions which unfortunately are not even alluded to in the book. Why did the bronze casting process fall into oblivion, and how did an artist such as Donatello succeed in reviving the lost wax process? This can’t be on the merit of one artist only, surely?

A book like this, however comprehensive it is, can never be complete (but well, which book is…?). Townsend and Zettle-Sterling are based in the US and have an obvious American preference in their choice of contemporary artists. Apart from one or two Europeans, and a complete lack of other continents, the reader will search in vain for well-known European jewelry casters such as Karl Fritsch, Gerd Rothmann, Peter Bauhuis, Ted Noten, or Stefan Heuser, or for European industrial designers who have employed ceramic and glass casting, such as Ettore Sottsass, Hella Jongerius, or Aldo Bakker. Industry, by the way, unfortunately comes down badly; there is nothing more than a sub-section that covers two pages with a minimum of text,[8] and interesting but scattered information in the essays. This denies the reality that the ceramic industry has profited a lot in the last decades by collaborating with artists and designers who “broke the mold.” There is an abundance of information in Cast, but the way it is ordered in chapters, sub-chapters and sub-sections, is not really successful, despite recurring topics such as “function,” “site,” “focus on…,” and “gallery.”

No matter my critique, Cast is a wonderful book, a delight to read and a stimulating delving into the subject. It is a rich and inspiring source of information, it will be a joy for art students, and it can become a reference for art teachers, with every page of the book burning with enthusiasm.