A Symposium Review

ThinkingJewellery 10—SchmuckDenken 10

On Our Way to a Theory of Jewellery

Art and good life – Art between leisure and social responsibility

October 18–19, 2014

Trier University of Applied Sciences, Idar-Oberstein

The unexpected German train strike during the weekend of the ThinkingJewellery 10 symposium could almost be interpreted as a response to this year’s theme of “art between leisure and social responsibility.”

The process of globalisation enters all areas of life: accompanied by the culmination of economical and ecological crises, ever-faster coming technical innovations…as well as the feeling of being overwhelmed[,] this process leads to a growing need for leisure and contemplation.[1]

Not to be outdone by the lack of travel options, over a hundred delegates and all but one presenter managed to arrive at the small town of Idar-Oberstein, which is known for its gemstone mining and cutting history and has, over the past 10 years, gained a reputation for developing a “theory of jewelry.”

ThinkingJewellery 10 was the 10th anniversary symposium presented by the Department of Gemstone and Jewelry at the Idar-Oberstein campus of the Trier University of Applied Sciences. The overarching aim of this annual symposium is to develop a theory of jewelry through academic presentations and contemporary jewelry exhibitions. Founded in 1986, the department offers both bachelor’s and master’s of fine arts degrees in gemstones and jewelry. The MFA is taught in English and, as such, attracts a cohort of international jewelry students (current enrollment has students from more than 18 countries around the world.) In the current climate of craft-based, higher-education courses being abolished, it is heartening to see the wide-ranging, traditional facilities for gemstone and jewelry hand manufacture being fully utilized. The department has established an international artist-in-residence program, which is currently occupied by the Australian jeweler Helen Britton, and also has an extensive exhibition program.

The symposium keynote speakers, selected by staff from the department—Wilhelm Lindemann, Professor Ute Eitzenhöfer, and Professor Theo Smeets—presented a range of theories in both German and English. Lindemann introduced the event, explaining that its intention was to open up the discourse on jewelry by considering its philosophical, anthropological, psychological, and sociological aspects. The contributing academics came from disciplines other than jewelry, including literature, psychology, and philosophy, with the latter being the most prevalent.

The first day began with a lengthy lecture in German from Professor Dr. Ursula Brandstätter, musicologist and rector of the Anton Bruckner Private University in Linz, Austria. For the non-German speakers, a version of her lecture was translated into English (it was disappointing, however, that the interesting photos and images shown in her slides were omitted from this.)

Over the course of the weekend, three practitioners presented their contemporary jewelry practice—Ute Eitzenhöfer, David Huycke, and Sarah Rhodes. With The Metaphorical Ornament: Philosophy and Way of Working, Professor Huycke described his exploration of the technique of granulation over the past 10 years, developed though his practice of silversmithing. Huycke, who trained as a jeweler (and teaches jewelry at the MAD-faculty, Hasselt/Genk, Belgium), described how he explores granulation. Granulation is not traditionally used in silversmithing, but rather is a decorative jewelry technique. Through his practice-based PhD research, Huycke explored granulation as a fabrication and structural technique, as well as experimenting with it conceptually. In his conceptual pieces, such as Moon (2005) or Meter (2007), he mostly works with the specific features of granulation, its formal and material qualities, experimenting with pushing the technique in different ways, viewing the resulting objects as sculptural rather than functional. Researching the transformational possibilities of granulation in silversmithing and jewelry, the work balances between sculpture and the domestic object, specifically being neither one nor the other. Huycke is predominantly a maker stating that making, doing things by hand, provides his ideas.

Professor Gisela Dischner and Professor Gernot Böhme delivered philosophical, academic papers. Their work overlapped with discussions centered on aesthetics and both quoted the Frankfurt School philosophers Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse. Böhme discussed an aesthetic capitalism, describing a new type of commodity value, that of staging yourself, which resonated with the current obsession with social media. He spoke about Benjamin’s belief that we all have a human right to be filmed, something that has contradictory connotations in today’s world where, if we live in a city, we are all constantly captured by CCTV, almost every minute of the day. He spoke about the politicization of aesthetics and drew parallels between nationalist and democratic aesthetics, arguing that there is little difference in the staging of political events between the two. He contended that few people are happy in the stressful contemporary world.

In contrast to the traditional philosophic perspectives set out by Dischner and Böhme, The Truth of the Moment: on the relationship between attention and art, presented by Professor Yuka Nakamura (psychologist and lecturer in development and health psychology, Zurich University of Teacher Education), really did give everyone a literal moment to pause and stop thinking when the speaker took us through a short meditative visualization technique. Her talk on mindfulness described the traditional Buddhist technique of being in the present moment. Mindfulness is increasingly being used as a method to combat today’s stressed world, as an antidote to being on automatic pilot where we can have “a serene encounter with reality,” as Nakamura quoted from the Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh. While mindfulness might be seen as a currently fashionable trend, it does have direct parallels with the jeweler’s practice of flow, or being in the zone, when making a piece of work.

Nakamura’s description of “the stillness that creates the space for creativity” was a theme also taken up by Professor Ute Eitzenhöfer, whose talk posed more questions for the symposium than it began with. She described her jewelry practice as a translation of words into forms. Inviting us to consider that translations are always “a bit out of focus,” she recounted inputting the Wittgenstein quote “everything we see could also be otherwise” in German into Google Translate, which became something else entirely when translated into English and changed yet further when translated back into German again.

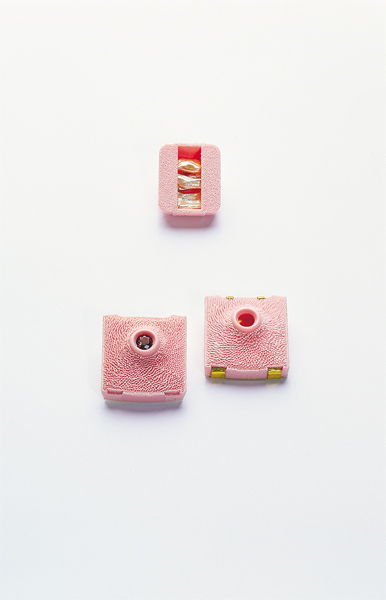

Photographs of Eitzenhöfer’s individual jewelry pieces made over the past 10 years illustrated each question as it was posed, explaining her stance of making to raise a question, and echoing David Huycke’s presentation, where he described learning through making. Engraved plastic bottle tops, set with gemstones and made into brooches, prompted Eitzenhöfer to ask, how are values defined? What is the worth and why?

After beginning the weekend with a train strike, it seemed a fitting end to the stay in Idar-Oberstein that some of the international symposium participants had to overcome a Lufthansa pilots strike to make their way out of Germany, the travel delays providing yet more time for contemplating “art and good life.”

[1] Schmuckdenken 10 online program, http://www.hochschule-trier.de/uploads/media/SD10_download.pdf, as accessed on December 23, 2014