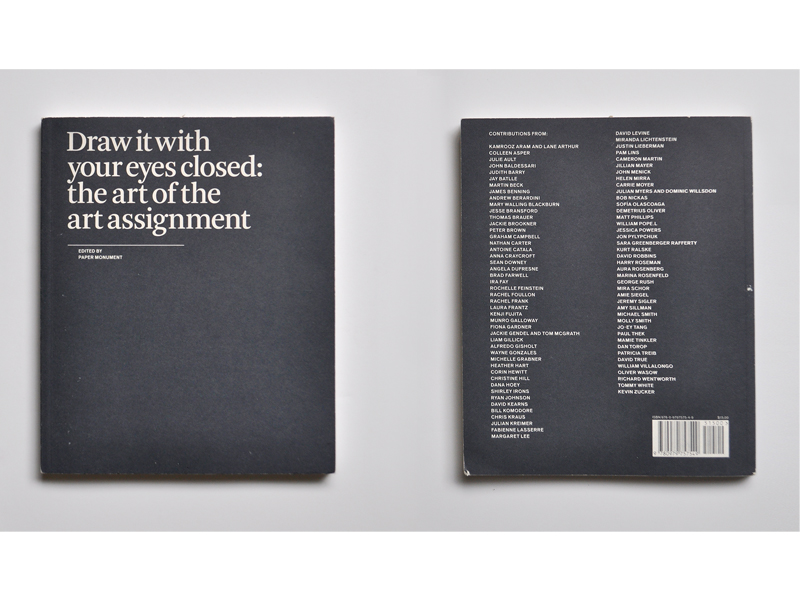

ISBN: 978-0979757549

Draw It with Your Eyes Closed: The Art of the Art Assignment is a multi-authored volume about art assignments, delivering them, experiencing them, and devising them, with many short essays and thoughts on their value and purpose. The anthology is produced by the Brooklyn-based not-for-profit publisher Paper Monument—responsible for a series of journals on contemporary art—and designed by Project Projects. It is a stylish book: slim, printed in charcoal black and creamy white on matte paper, every page divided into two columns, with well-chosen fonts to demarcate headings from prose.

As explained by the editors in the afterword, the publication stemmed from dissatisfaction with the lack of attention to the “nuts and bolts of art teaching,” despite the plethora of material on art pedagogy and the history of the art school (page 122). The editors wanted to produce a practical, hands-on “book of art assignments,” so they asked contacts, friends, and friends of friends to relay their experiences of setting and participating in them.

In the book, there is such a wide range of responses to this call, from clear technique-based tasks—such as David True’s circumvention of still life by asking students to create a pile of boxes each colored a different shade of white as a composition for their painting (page 89)—to more experimental assignments. Kevin Zucker’s “Bring in a song you’re embarrassed you like/bring in images of past work you’re embarrassed by” (page 14) is just one example that challenges the hierarchical notion of proactive teacher passing down knowledge to passive, receptive student.

Despite the huge variety of contributions from “people who teach, people who study, people who teach but didn’t study, people who studied but don’t teach, and people who never set foot in an art school” (page 122), it is possible to group the content into three distinct categories. There are examples of assignments that you could roll out in class next term, almost like a how-to, such as Ira Fay’s “Sports Assignment” (page 28), Julian Kramer’s “Wet-on-wet large still life,” (page 49), or Paul Thek’s comprehensive list of questions “Teaching Notes: 4-Dimensional Design” (pages 78–80). Then there are first-person narratives of particularly memorable, impactful, and funny art assignments like the one issued to Brad Farwell during an undergraduate architecture course that involved Farwell and fellow students building a scale-model façade out of cake, without the assistance of any “mortar” (i.e. icing) (page 69), Jeremy Sigler’s account of his experience at New Haven Institute of Technology (pages 107–110), or Mamie Tinkler’s account of how “a muddy wreck of a canvas” stuck in her mind as an instructive art school humiliation.

The third category comprises entries that offer broader commentary on artistic education, including many that question the value and purpose of the art assignment in the first place. Among these is Jon Pylypchuk’s petulant dismissal of the art assignment and his delight at a strike that kept the professors at arm’s length during his journey of artistic discovery (page 75), and Liam Gillick’s argument that assignments are like homework, creating “an artificial power relationship between student-artist and older ex-student-teacher-artist,” that replaces “the potential for real work and real recognition of power dynamics” (page 119). Paul Thek’s long list of questions that “stimulate a playful but in-depth exploration of the interrelated nature of personal and contextual events, as a part of artistic production” (page 71) looms large in the book: It is reprinted in full, and several teachers and students— Harrell Fletcher, Abraham Cruzvillegas, and Naomi Rincon-Gallardo—recall their responses to it (pages 71–74).

Many of the book’s entries show how a limitation, or setting an unexpected obstacle, is integral to the art assignment. Designed to knock students’ preconceived notions of art off kilter, they seem a popular way of prompting creative thinking and practice. Material constraints feature throughout: Lauren Frantz asks students to make a drawing on a sheet of paper only using a car (page 12), Sara Rafferty’s assignment involves trying to make a device that would protect an egg dropped from three stories using a napkin, string, oyster crackers, and corrugated cardboard (page 31), and Demetrius Oliver recollects a 3-D design brief that involved making something in a forest way off-campus with the “materials available at hand” (page 33), à la Henry Thoreau.

The book contains many tales of radical, unconventional briefs and students’ extreme responses. Jeremy Sigler recalls a video work that involved a female student being punched “in the face hard by her boyfriend” (page 107). Kevin Zucker advises that art instructors should not let 19-year-old students know about Viennese Actionism for fear of unleashing something “genuinely shocking” on impressionable minds (page 15), and Jay Battle remembers a student reenacting Yves Klein’s famous leap into the void, the performance ending in broken legs because a branch meant to provide the means of escape was cut down (pages 105–106).

The collective experience reflected in the book demonstrates how the art assignment often ventures into dicey ethical territory—a number of contributors mention that higher management within the academy would not approve of the things that take place in their class in the name of education. Flicking through the book, it is not hard to see why. The clandestine course in making pornography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (Amie Seigel, pages 100–101), the “Project Class” that John Menick participated in that involved keeping a secret within the class walls (page 61), and Julie Ault’s self-assignment “Don’t be Yourself” (pages 88–89), where she assumed another identity as a Republican supporter in order to fit in with the culture of political science at Hunter College, all test the limits of what is acceptable within institutes of higher education. They also reveal a recurrent theme in the book: the difficulty, or impossibility, of teaching art, where it is debatable that any sort of guidance, syllabus, or structure that determines progress exists in the first place.

The book left me wondering whether my own mantra of learning and teaching in my role as lecturer in design history—the tutor as dispassionate provider of knowledge and experience, or enthusiastic encourager of self-development—is relevant to the instruction of artists. Staff with close contact to the studio, including teaching assistants and technicians, often become embroiled in the lives of students (one particularly extreme example of this is Peter Brown’s tale of teacher-student romance that ends up in marriage and children on pages 66–67). The division between art and life is, of course, a fabrication. Nevertheless, I would insist upon a distinction between “my” life and “their” art when operating in an institutional context, if only to confirm my position (as a lecturer) held to the codes of conduct stipulated in my contract.

There is an American bias in the work. Throughout, there are lots of references to “freshmen,” including a fun illustration, “Freshmen Eyes,” by Pam Lins, that starts the book. The language is not the problem, though, nor are the specific cultural references. It is more the current pedagogic and institutional cultures of the American art school that stress individualism, the expectation that art occupy a counter-cultural position and “rage against the machine,” which might be less relevant to those based in Europe and elsewhere. Richard Wentworth is one of the few contributors from Europe. His gentle reflection on the internationality of art education today, and the myriad responses to a brief that involved charting a journey within London, bring attention to “a complexity” within globalized systems of twenty-first century artistic education he never anticipated (page 115).

There is an American bias in the work. Throughout, there are lots of references to “freshmen,” including a fun illustration, “Freshmen Eyes,” by Pam Lins, that starts the book. The language is not the problem, though, nor are the specific cultural references. It is more the current pedagogic and institutional cultures of the American art school that stress individualism, the expectation that art occupy a counter-cultural position and “rage against the machine,” which might be less relevant to those based in Europe and elsewhere. Richard Wentworth is one of the few contributors from Europe. His gentle reflection on the internationality of art education today, and the myriad responses to a brief that involved charting a journey within London, bring attention to “a complexity” within globalized systems of twenty-first century artistic education he never anticipated (page 115).

It is connections like these—between discrete assignments and wider cultural contexts of artistic education—that are lacking within the anthology. Too many of the assignments are seen within the bubble of the studio, where anything is potentially permissible, without relating much to art’s position within the academy and indeed institutional pressures operating at one level above the tutor-instructor.

Exceptions to the rule include James Benning’s brief reference to the increasing bureaucratization of art departments and how his institution’s current fear of lawsuits has curtailed his ability to run off-site classes (page 120). But it was Mira Schor’s longer reflection (pages 90–91) on the importance of her assignment, “You have permission to fail,” that best illuminated current contexts of artistic education. She brings attention to the “corporate atmosphere of educational institutions” and the pressure to provide students a full program that sets them up for success in later life, which she analogizes as a “military quadrille.” Instead of venturing into the unknown, art students are under significant pressure to reach a defined, intended outcome in their work, succumbing to “self-commodification,” Schor suggests, utilizing languages of formalism, subjective expressionism, and conceptualism that “at least on the surface, seems to reward rationalised concordance between visual appearance and verbal articulation, a to b.” Her point is that packed schedules—“the appearance of instruction and of money’s worth”—result in students unwilling to take risks, relying on expressions of their own intention to justify their work.

The publication is an undeniably useful source book of ideas for artist-educators, even if as an educator you would do it differently or modify some of the ideas to your own demands. Ensuring that the art assignment allows a place to fail, to not be quite sure, to explore and experiment with the material world surrounding us, will lead to unpredictable, but ultimately humane, experiences like those recounted in this book. Today’s approaches to teaching art and design might seem eccentric and marginal when compared to other forms of instruction within the academy. Yet let’s hope the art assignment’s openness, liberal mantra, and insistence on enabling students to think for themselves might yet escape the managerial turn in higher education, providing invaluable and transferable skills for students in the future.