KAФEDRA: Exhibition by the Department of Jewellery and Blacksmithing

April 30–May 29, 2016

Narva Art Residency, Narva, Estonia

KAФEDRA is a multifaceted exhibition showcasing the work of the department of jewelry and blacksmithing at the Estonian Academy of Arts. It was organized by Kadri Mälk, Sofia Hallik, Piret Hirv, Eve Margus-Villems, Nils Hint, and others in the academy, and it is a sprawling affair, made up of five different, smaller exhibitions, and featuring more than 400 objects by 70 makers.

Taking place in Narva, the third largest Estonian city, right on the border with Russia, the exhibition is located in the Narva Art Residency, an old brick villa that was part of the Krenholm Manufacturing Company, a textile mill that was at one point the biggest cotton-spinning and manufacturing mill in the world, and is now a vast industrial ruin. The villa was built for a British engineer, who refused to move to Estonia and take up his new job until his house was finished. What remains are charmingly worn rooms, with lots of exposed brick, old wooden floors, and peeling plaster on the ornate molded ceilings. This is the kind of space that art increasingly inhabits, the ruins of industry transformed into the sites where artistic activity can flourish as part of the post-industrial culture complex.

Too often these old buildings are distracting as a venue for art, because the building itself fights for attention and imposes too much on the objects on display. But with jewelry it works nicely: partly because these rooms are domestic, in however grand a manner (and jewelry usually inhabits domestic, rather than gallery, space); and partly because the scale of jewelry demands display furniture, constructions inside the rooms that create surfaces on which the objects can be placed, therefore distinguishing the jewelry and architecture.

And what smart display furniture this exhibition offers. The gallery dedicated to the main presentation of the student work, mostly Bachelor of Arts students, features constructions of red-painted fiberboard arranged into sloping surfaces that exist somewhere between household tables and factory constructions. The two winners of the 2015 Young Jewellery collection award, Sofia Hallik and Darja Popolitova, have their work displayed on old cast-iron hospital beds that have had one bed end removed and the springs replaced with black-painted fiberboard. Leaned against the wall, the beds also hover between two zones (the home and the hospital; the table and the wall; jewelry and sculpture). The results of the workshop, with Spanish jeweler Gemma Draper, on the theme of “Rituaal” are displayed on black-painted fiberboard platforms with hemisphere legs, rockers that are wedged into place on an angle, making them uncanny tables or uncertain plinths. Somehow it appears much more high-class than the materials should allow. And while you could imagine these display strategies slickly fabricated in laser-cut metal, the everyday and cheap character of the materials and construction methods fits the space perfectly. The wit in responding to the history of the building as a house is matched by an awareness that this is a villa in decline, a wreck that has been arrested in its transformation from elegant domesticity to ruin.

Perhaps you’re wondering why I’m talking so much about the exhibition furniture and the building, and not about the jewelry, which surely is the main point of an exhibition like this. Well, this isn’t going to be a typical review, because I don’t believe it is possible, or appropriate, to review student work—and at heart, and for the most part, this is an exhibition of things made by students of the Estonian Academy of Arts as part of their studies. While there is definitely a place for critique in the learning process, this happens in quasi-private contexts, not in public venues like the Art Jewelry Forum website, and its purposes are different—to encourage students to think differently about what they are doing, to model what robust practice looks like, and always within a framework that acknowledges the context of study and the acceptability of failure.

Critical reviews don’t have the luxury of offering apologies or excuses, including that the makers in question are still learning; and without that framework, this review would become a litany of failure, of descriptions and analyses of things that really aren’t good enough when compared to the best in the field of contemporary jewelry. (The majority of this jewelry is just as you’d expect from any group of BA students anywhere in the world—which is to say, it looks like student work, like the results of people learning how to make objects that belong in the field of contemporary jewelry.) There are also other difficulties. Objects and practices can’t stand out in the context of such a large amount of work, or will only stand out for reasons that may not be a mark of quality or excellence. There is too much to see, and too much I don’t understand because of my language limitations, and the limitations of information that is provided by the gallery model. What I am hitting here is the limits of the review format.

But it does become possible to think about this exhibition as a presentation of the department itself, and of the way it seeks to locate itself as part of the scene of contemporary jewelry. In that sense, I am impressed by the seriousness of the whole endeavor, the care that has been taken to showcase what, in the most part, is student work—and is therefore as uneven and provisional and conventional and incomplete as you’d expect from people still learning their craft. What’s on display here is an ambition about what it means to stage an exhibition, and how committed one should be to the opportunity. Whatever happens to the individual students who graduate from this school—whether they end up making good or indifferent work—the institution itself, based on the evidence of this exhibition, is a dynamic place with big ideas.

An example of this that I am still not certain about, a week after seeing the exhibition, is a room of videos, short … advertisements? … art films? … that activate some of the works on display in the other galleries, and especially the ones made as part of the Rituaal workshop. These videos are strange, partly because they can’t easily be categorized within a genre: they are not straightforward documentations of the objects in use, but poetic or theatrical. Some emphasize the wearer or user while others the object and making process; the visual language is slick, and perhaps closer to advertising than fine art, bringing to mind advertisements for luxury brands. I find them quite enriching to my experience of the exhibition, even as I can’t decide what I think about the videos themselves. Projected onto the wall of a darkened room, away from the individual objects that the viewer encounters elsewhere, these videos become less about the work and more, to my mind, a statement of the overall ambitions of this project, a signifier of intent to move beyond the common or expected devices of a jewelry show.

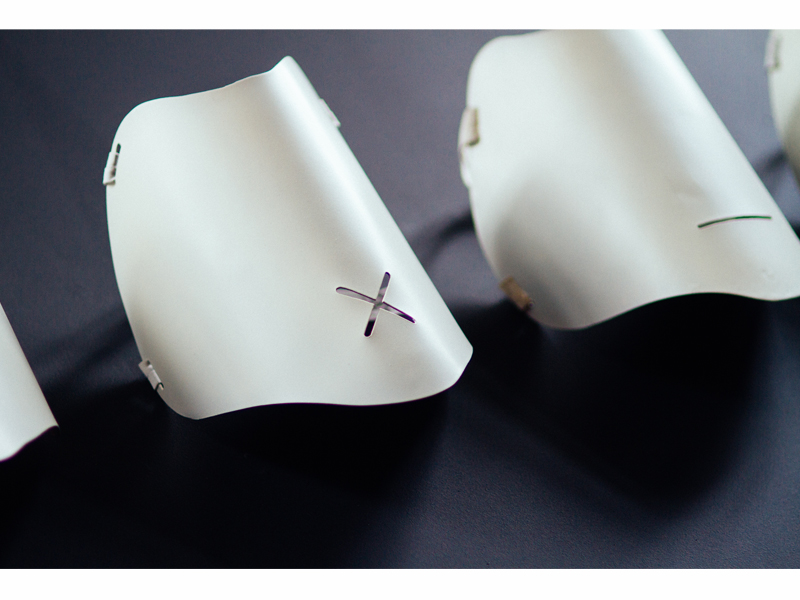

Of all the objects on display in KAФEDRA, the four makers in the room titled “Sümptom” are the ones who might be reviewed seriously, so this is how I’d like to finish. Hanna-Maria Vanaküla has made a series of pendants and brooches, each constructed from the same glossy and dense black substances, as if chunks of petrified wood or obsidian has somehow extruded nipples. Contemporary jewelry’s interest in materiality comes into contact with the body as a subject. They are well done—resolved, visually interesting, wearable, and strange. You can imagine them in a gallery, or a collection. This is what contemporary jewelry looks like.

Sofia Hallik has made neckpieces and brooches with titles like Nymphe and Homeosis, which are smooth geometric ovoid forms of different materials, such as stone, glass, and polyurethane. At work here is symmetry, the attraction of polished surfaces that operate both visually (light reflections playing on strong shapes) and tactilely (objects that the wearer will touch and hold rather than just wear). The titles are suggestive, but not intrusive enough to disrupt the abstraction, and the work is again very resolved.

Merlin Meremaa’s Hingetomme are frosted glass funnels without pins or chains, which makes them objects rather than jewelry. Different shapes and sizes suggest funnels that might be used to pour liquids from one container to another, as well as funnels that might be part of a machine. Unlike the rest of the objects in this room, these are not so gallery ready—which is to say, they fit a bit more oddly into the category of jewelry, and therefore raise questions about what they are, and what you might do with them.

Finally, Darja Popolitova’s brooches and pendants are smooth and curved carved forms of wood, sometimes set with ovoids of glass, and in one case, a faceted stone in a claw setting. Some look like strange fruit, or distorted buds and pods (what I think of as an Estonian effect of twisted nature), while others offer strong geometries and contrasts of materials (satiny wood set against fine-grained stone). Again, this jewelry is resolved and gallery ready.

In the press release for this exhibition, the academy noted that unlike previous exhibitions of the school’s work, this one was being held outside Tallinn, the capital city of Estonia and the location of the school. “This time the exhibition reaches out geographically and showcases the department in Narva—the border town of the European Union and Schengen Zone—from where many talented students have come to study [at] the Estonian Art Academy.” This was my first visit to Estonia, and traveling to Narva was a stark reminder of how little I understand—about the country and its history, but also, by extension, about this jewelry and the school it represents. Right on the border, in a city that is 93% Russian-speaking, some of our Estonian colleagues professed to feeling uneasy, given recent political events between Russia and the European Union.

Such a competent and ambitious exhibition no doubt obscures other border zone activities that inform the work of the school, and shape the students who study there. These remain invisible to me—I found it thrilling to look across the river and see Russia, right there, and not at all threatening. But thinking back on the exhibition, I begin to imagine their effects: the oblique and unusual attitude to nature, the subdued mixing with the ostentatious in material and form, the strangely assertive and yet also tentative appeal that contemporary jewelry makes to the viewer/wearer. What might more properly be ascribed to the condition of being a student becomes suggestive of a larger cultural dynamic. For this viewer, this uncertainty is one of the most memorable things about KAФEDRA.

INDEX IMAGE: Exhibition view, the Sümptom room, KAФEDRA: Exhibition by the Department of Jewellery and Blacksmithing, 2016, Narva Art Residency, Narva, Estonia, photo: Dmitri Leshihin