(IM)PRINT

February 24–28, 2016

easy!upstream, Munich, Germany

Curated by Beatrice Brovia, Nicolas Cheng, Hanna Hedman, and Kajsa Lindberg

They say that money makes the world go round but, really, it is printing that deserves this accolade. In a literal sense the banknotes and coins of our currencies derive from complex processes: The background design of the 5-pound note in front of me now is printed in offset lithography, the Queen’s head in intaglio, and letterpress is used to give the note its unique serial number.[1] Metaphorically, it is the (im)print on the material world that money facilitates that is significant, shaping the exertion of human-technological labor, the mobilization of power, and assertion of identity, whether that be in the form of building a factory, buying a statement brooch from a studio jeweler, or pressing the nib of a Bic pen into the fresh plane of a birthday card message.

Thoughts of banknote printing, impressions of money, and circular flows of labor and capital were bubbling away in my head during my visit to the group exhibition (IM)PRINT on show at the easy!upstream gallery in downtown Munich during Schmuck. For jewelers, stamping, impressing, inscribing, etching, setting, hallmarking—the full range of (im)printing processes—are part of the daily grind. Perhaps this means that jewelers are uniquely placed to critique our relationship with printing, distribution, publication, and money.

As I entered the exhibition, I was drawn down the long, narrow, white-walled space to Yuka Oyama’s video piece, Helmet River.[2] Perhaps it was the attraction to the crisp, moving image on a large flat screen that led me to the end room, or the need to get past the café and small bookshop at the front of the space, which suggested participation.

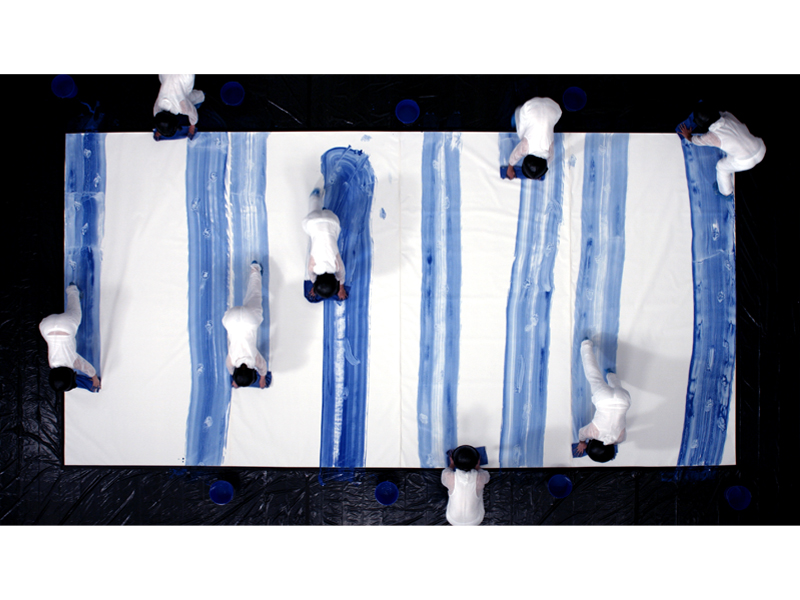

The video showed a tightly controlled choreography of nine people (two lines of four with one leader out front) entering what looked like the hall of a neoclassical rotunda. They wore white outfits with cellophane overcoats and disturbing black snorkel masks, akin to the headgear of Kylo Ren, the aspiring Darth Vader in the recent Star Wars film. To orders barked out by the diminutive leader, the eight participants, each equipped with a cotton towel and watery blue acrylic paint in a blue bucket, crouched at the ready on either side of a large rectangular canvas on the floor and then proceeded to push their charged towels across the canvas, making streaky blue marks. This was not like Pollock’s drip paintings, replete with spontaneity and artistic expression, but a tightly controlled orchestration, painter-workers pushing a towel up and down a floor in a humiliating and self-destructing ritual. The footsteps of each participant immediately marked the just-painted section of floor, and they stuttered and faltered as a result of the slipperiness of the surface they were creating. The video recalls similar ephemeral choreographies of labor, from Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen’s assembly line/dance 75 Watt (2013), shot in the White Horse Electric Factory in Zhingshan, China,[3] to ceramist Simon Carroll’s beach drawings, pattern designs normally seen on pots etched into the sand with a humble rake.[4] Yet Oyama’s video is a depiction of repetitive, controlled, and alienated labor. It is like watching multiple Cinderellas wash the floor for their ugly sisters, impairing the result as they go.

And in the opposite corner of the room, the golden calf, the end goal of the types of industrial work scenarios parodied in Oyama’s video. Money. Profit. Multiple dollar signs of different sizes embroidered in pale pink on the plastic glossy surface of a foam lump in a Beatrice Brovia necklace.

This suggested narrative highlighted the longstanding relationship between jewelry and conspicuous wealth—priceless diamonds and gems in Swiss safety deposit boxes. Around the corner from Brovia’s work was Göran Kling’s kinetic installation that presented 24 gaudy rings within an opened, cheap jewelry box, spinning slowly atop a plinth robed in black velvet. Tampered coins, a dime with a peace sign cut out, for example, were pressed into the settings, and other bands had acid smiley faces or text-speak (things like “4ever”) emblazoned on them. Kling’s marks point to histories of coin debasement, but it is the rotation of these cheap bits of bling, as if in a shop window’s display case, that returns the mind to Oyama’s obedient but doomed painters. The circulation of money and labor made material in critical, ironic works.

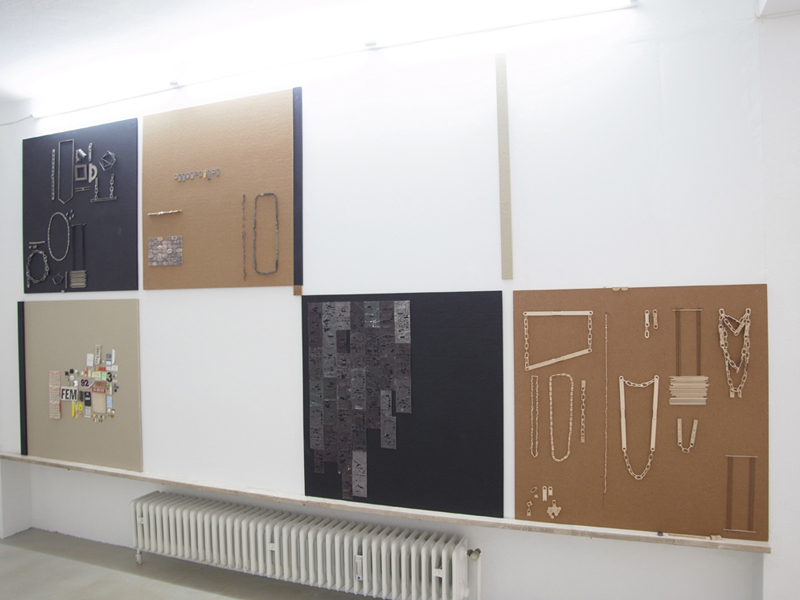

Money goes round and round, as does a ring: Is it a halo or a tag? Presumably the former for those visitors who have bought one of Silke Fleischer’s long line of simple, elegant rings, their colors bleeding from gold to silver to copper, with conspicuous gaps in the series signaling acquisition. Fleischer made the rings one after the other, transforming each one ever so slightly as she went, an allusion to the variation possible within tight structures of serial production, much like the strips of blue paint in Oyama’s piece. Next to this piece, Kajsa Lindberg presents her own investigation of money and number. On one side of the gallery a series of receipts are pinned to fiberboard, with the numbers from these receipts carefully cut out and presented on the opposite wall as a mirror image. The receipts, minus the numbers, have been blackened by the heat and pressure of an iron, giving them the appearance of charred punch cards for a jacquard loom. This fossilizes the receipts, unearthing a range of crystalline surfaces, unexpected splendor contained within the most throwaway of materials that we use as records of our transactions.

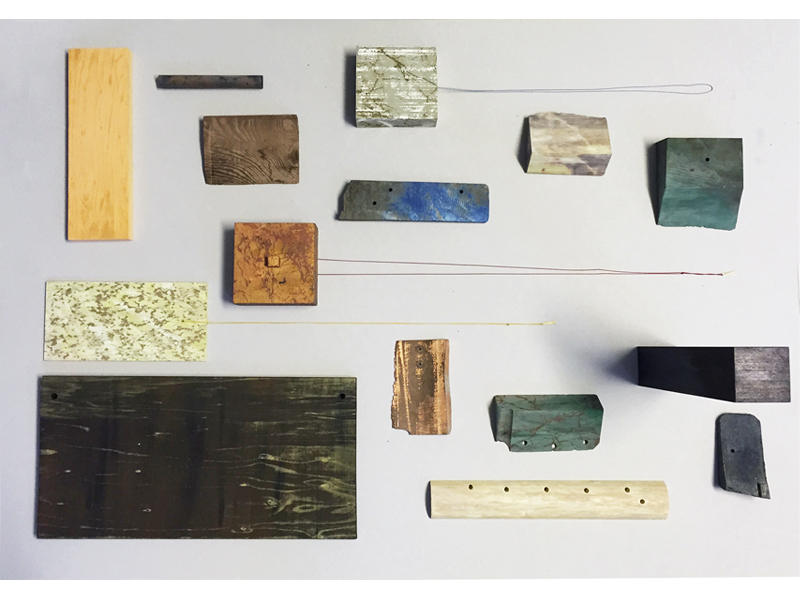

By this stage my own eyes were printed with dollar signs, certain that the materialization of money and its circulation was the main theme of the exhibition. But critical reflection on the materialization of money, consumerism, and repetitive labor was not a theme in all the works. For example, Niels van de Wouwer’s prints of botanical drawings and Nicolas Cheng’s exploration of “future archeology or material frictions,”[5] in what looked like a range of material samples, responded to the techniques and tools of print. Then there was Hanna Hedman’s book, Murmuring (2016), full of spectral, mystical, biological jewelry that had little to do with money. It was an (im)print in a direct sense, a publication. Indeed it was Hedman’s book that initiated the project in the first place: The young collective of artists and curators behind easy!upstream, a temporary gallery/café/bookshop that will run until November 2016, had been in touch with the artist about the launch and offered the whole space for the exhibition during Schmuck to bring contemporary jewelry to their predominately fine art audience. The title (IM)PRINT emerged in early 2016 from conversations between Hedman, Brovia, Lindberg, and Cheng. Their intention was to look at publishing in the broadest possible sense and include works that “allude to the ways objects imprint on us just as much as we think we imprint them; or the connections between jewelry language or jewelry-typography.”[6]

This rationale is quite vague and would actually accommodate most jewelry, even most objects, as imprints between human and object are always reciprocal. In regards to “jewelry language,” there were multiple responses to this idea in the first room. Nils Hint’s screws, cutlery, and tools pounded into brooches by the weight of his Soviet-made 5000-kg hammer are indexical shadows of objects;[7] David Clarke appropriates the language of the silver spoon, presenting a flat-headed spoon in a vintage display box alongside multiple photocopies of his sketches/ideas; and Liesbet Bussche’s posters present simple line diagrams of jewelry typographies on blueprint paper—including “cocktail ring,” “stud,” “statement necklace,” and “strand of pearls.” But I read Bussche’s posters according to the theme already firmly entrenched in my head—money, number, matter. The title of her work 11 Pieces of Jewelry Every Woman Should Own alludes to our quantification culture, the idea that we have not lived until we have been to the 10 places to visit, or gotten through 10 must-read books, before we die. The pressure of these “have-to-do” lists appeal to a number, measurement, and, ultimately, money-obsessed society, rather than one that privileges the quality of any experience.

By giving free reign to artists to investigate ideas of publishing in the broadest possible sense, the (IM)PRINT team opened up many potential interpretative pathways through the exhibition. I found the investigation of money and its materialization the most convincing way to navigate the space, but certain works could not easily be read into this narrative. However, the thematic focus, albeit broad and multifaceted, provided space for the visitor to interpret and work with the artists’ ideas. Individual works did not drain your attention and the viewer was allowed to move away from the object focus so common elsewhere and consider the correspondence between works in the gallery. It was much appreciated in the febrile atmosphere of the international contemporary jewelry fair, a moment of self-reflection on the circulation of money, number, and matter going on all around us.

INDEX IMAGE: Nils Hint, Shadow, 2014, brooch, forged iron, circa 30 mm high, photo: Benjamin Lignel

[1] The Bank of England is responsible for the production of UK banknotes, but the actual production of the notes using these techniques is executed by De La Rue Currency, a subsidiary of De La Rue plc. For information on the printing of UK banknotes, see “Production” on the Bank of England website, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/banknotes/Pages/lifecycle/production.aspx (accessed March 13, 2016). For an overview of the printing process of currency, see “Production of the new 10 Euro banknotes – printing Bills EUR BCE USD Money as Debt” on YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3bFPahz39e0 (accessed March 13, 2016).

[2] Yuka Oyama, Helmet River, 2015, video, http://www.yukaoyama.com/#!film-helmet-river/c10wl (accessed March 13, 2016).

[3] Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen, 75 Watt, 2013, http://www.cohenvanbalen.com/work/75-watt (accessed March 13, 2016).

[4] Simon Carroll, Beach Painting 2 (2007), http://www.simoncarroll.org (accessed March 13, 2016).

[5] (IM)PRINT press release. easy!upstream, Munich (February 25–28, 2016).

[6] Email from (IM)PRINT team (March 8, 2016).

[7] Stephen Knott, “Shadow,” Art Jewelry Forum (April 30, 2015), https://artjewelryforum.org/articles-series/nils-hint-shadow (accessed March 14, 2016) and reprinted in Benjamin Lignel, ed., On and Off: Jewelry in the Wider Cultural Field (Mill Valley, California: Art Jewelry Forum, 2016).