The gallery in which Jewels, Gems, and Treasures is housed is a reasonably small, square space, with freestanding cases lining three walls, and a built-in case on the fourth wall. The cases are lit from within and the carpet, walls and ceilings are colors that recede, so that we are left with the contained areas of the cases and the objects sparking in their shallow cases. The gallery was busy on the Thursday that I visited, a steady stream of people shuffling from case to case, murmuring to their friends about what they were looking at. The atmosphere isn’t somber, but respectful, absorbed and quietly amazed, rewarding attention and a slow pace.

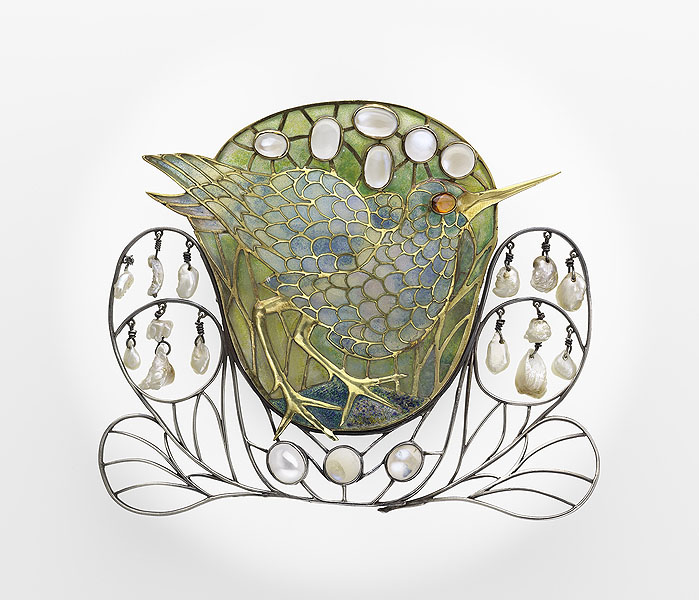

There isn’t a catalog for this exhibition, but many of the objects on display in this gallery are also featured in Markowitz’s Artful Adornments: Jewelry from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which was published to mark the opening of the Rita J and Stanley H Kaplan Family Foundation Gallery in which Jewels, Gems, and Treasures is on show. It is a chance to see old favorites, such as the Egyptian pectoral (1783-1550 BC, possibly from Thebes, of gold, silver, carnelian, glass) or the Hathor-headed crystal pendant (743-712 BC, Nubian, made of gold and rock crystal) or the coral revivalist suite (1840-60, Naples, Italy, of gold and coral) or the feng tien (headdress) (Chinese, c.1900, gilt metal, kingfisher features, jadeite, tourmaline, coral, turquoise, lapis lazuli, bone, pearl, glass, resin, silk) or Charles Robert Ashbee’s Marsh Bird Hair Ornament, now a brooch (1901-2, gold, silver, enamel, ruby, moonstone, freshwater pearl). Again Markowitz displays her talent for condensing a great deal of information in a pithy, informative and accessible text. Here, for example, is what we find out about the coral necklace:

After a general introduction, which provides the history of the MFA’s jewelry collection – what kind of objects entered the museum, when and how – Markowitz divides the book into categories: ‘Magical Jewels,’ ‘Emblems of Wealth & Power,’ ‘Tokens of Affection & Remembrance,’ ‘Dress & Adornment,’ ‘Jewelry & the Avant-Garde.’ These introductory texts are necessarily general, spanning a few pages each and covering hugely diverse geographical regions and time periods, yet this is supplemented by the detailed accounts of each piece that follow, including a very well-written text, plus further readings through footnotes. There is a glossary, further reading section and an index, which make this a useful book for specialists as well as the general public.

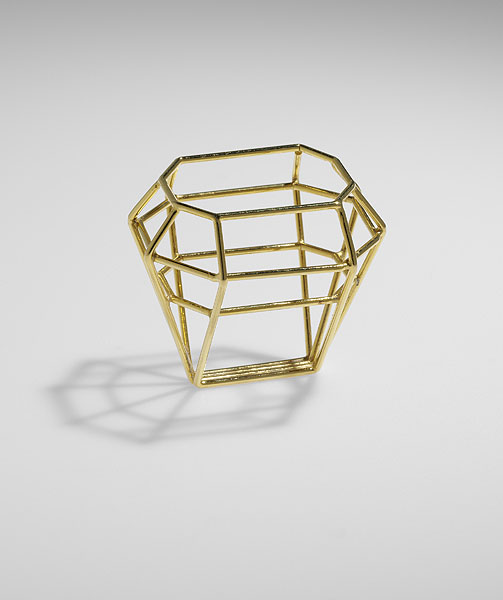

Like the exhibition, Markowitz’s focus on the role of jewelry allows her to pull together a collection of objects that otherwise wouldn’t make sense. Contemporary jewelry, for example, is not only found in ‘Jewelry & the Avant-Garde,’ but turns up in ‘Magical Jewels’ (Kiff Slemmons) and ‘Tokens of Affection & Remembrance’ (Lisa Gralnick and Daniel Jocz). It isn’t even the star of the show in ‘Jewelry & the Avant-Garde,’ which takes in the arts and crafts, and art nouveau movements at the beginning of the twentieth century, before ending up with studio jewelry. Again, what is so nice about this approach is that contemporary jewelry is restored to a larger world of adornment and jewelry, and jewelry is restored to being about more than precious materials. It is, so Markowitz’s exhibition and book seems to suggests, okay to be dazzled – and paying attention to sparkle doesn’t have to mean turning jewelry into objects that are all surface and no depth.