That the art of Southwestern jewelry connects intricately to Native peoples’ contacts with 19th-century visitors to their homelands is a key takeaway of the Jim and Lauris Phillips Center for the Study of Southwestern Jewelry at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Staggering collections of jewelry, hollowware, horse adornment, and plugs of stone carved into animal fetishes represent smithing and lapidary histories spanning 1870 to the present. Nearly 750 objects are exhibited in the center. The museum spent a decade collecting the trove from various sources; the gift of the Phillips collection itself arrived in 2013. That gift precipitated the Wheelwright’s building of a new, 2,000-square-foot wing in which to exhibit it. Behind its selection and presentation are longtime museum director Jonathan Batkin and curator Cheri Falkenstien-Doyle.

Opened in June 2015, the 1,600-square-foot Martha Hopkins Struever Gallery that houses the center is a clean, well-lit space named for a prominent Santa Fe dealer in American Indian jewelry. The Schultz Gallery, a 400-square-foot space next door, is dedicated to changing exhibitions.

Illustrating histories of colonial contact manifest in jewelry is a complex idea from the get-go. So is showing a permanent collection of jewelry as a “study center.” Since its 1937 founding, this museum’s engagement with Native artists and voices is a keystone of the story.

Bostonian Mary Cabot Wheelwright was the Wheelwright Museum’s eponymous founder. Living in Santa Fe, she met and befriended Navajo singer and medicine man Hastiin Klah. Wheelwright recorded Klah’s song of the Navajo creation story, and had the idea that archiving and preserving oral histories and their materialization into objects was essential. [1]

In the case of the Phillips Center, the object lesson imparted by the case-upon-case of eye-dazzling objects persists alongside an elaborate if inefficiently presented narrative reconstruction that wants to lean heavily into anthropological documentary.

That reconstruction attempts to map how jewelry’s material practices among Southwestern tribes evolved. Panels of text are tucked inside of individual vitrines, so that a viewer has to actually work to read and take in very fine points about when techniques were learned, how they passed among pueblos and tribes, and how diverse Native peoples incorporated them with decidedly individualist twists into their own material practices.

The visual flair and drama embodied in the room attest to Native peoples’ indelible creativity. Further, the room writes a map of the instinctive travels of symbols through its objects—like the inverted crescent that is the Navajo pendant, typically on a squash-blossom necklace, called the naja. The naja has DNA as old as the goddess Astarte and the Moors’ multi-century occupation of Spain. It was hung around the necks of camels as an ornament. On the bridles of Spaniards’ horses traveling north through the Americas, the symbol conveyed protection for soldiers and steeds. The Navajo, in turn, took it from the Spaniards.

Entering the Struever gallery, one is instructed by a center kiosk to turn left to start circumnavigating the wall-inset cases in chronological order. On the way to the back, one passes between a pair of cases starring the works of father-and-son Navajo silversmiths, the Peshlikais.

The elder Peshlikai (roughly 1830–1910) went by the name Slender Maker of Silver or “Old Peshlikai.” He was the first known Navajo silversmith. (His Navajo name was Atsidii Sání.) Among his achievements was launching a jewelry business. Slender employed more than 10 silversmiths in a shop, according to what his son, Fred, told photographer-archivist John Adair in 1940s Los Angeles.

Around the corner from Slender Maker of Silver’s vitrine, inside a case with the title “Men’s Adornment,” are the mid-19th-century men’s accessories that a photograph of Slender recorded him wearing—leather leggings studded with silver buttons.

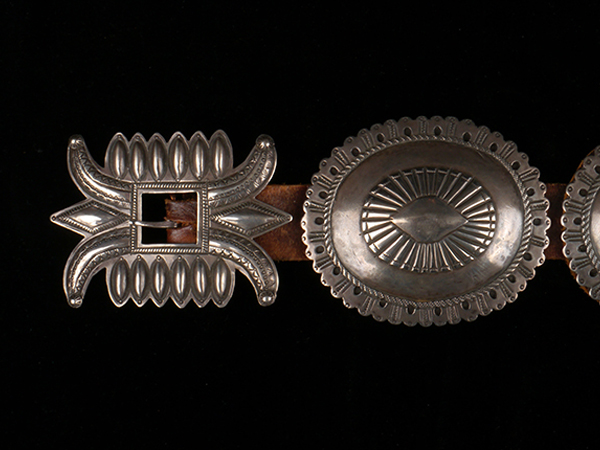

Other of the eldest southwestern smithing traditions of note are Slender’s concha belts and silver-beaded necklaces hung with najas. They have a presence that is hard to underestimate; the oversized “conchas” (seashells) correspond to a radically streamlined, nearly modernist form.

Slender’s son, Fred Peshlikai, became a turquoise specialist in Los Angeles in the 1930s; he bought his stones directly from a mine owner named Doc Wilson. Fred Peshlikai’s work attests to lapidary itself becoming dominant in ways suggestive of pop-culture influences. A matching pair of 1960s rattlesnake arm bracelets is bold enough that one could imagine Elizabeth Taylor wearing them.

Much of what was learned about adaptations of jewelry at Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi sites was the work of 19th-century anthropologists and archivists such as Frank Hamilton Cushing, who traveled to Zuni pueblo in 1879, or John Adair, who conducted oral histories at Navajo Nation and with the Hopi tribe beginning in 1938. Cushing, who had arrived at Zuni with John Wesley Powell of the Bureau of Ethnology, lived among the Zuni from 1879 to 1884 as a “participant observer.” In the 1930s, Adair wrote down the oral history of Lanyade, the first Zuni silversmith, 95 years old when he told Adair how he had learned his trade (from Slender Maker of Silver, the Navajo, in 1872.)

Visually speaking, one of the most palpable arenas of difference in Southwestern jewelry lies in the dominant use of silver, turquoise, and coral among the Navajo, and the stone and shell used by Zuni and Hopi jewelers. Starting as early as 600 AD, the Zuni traded bison hides for shell, coral, and seawater. The spondylus shell that details the naja on a 1900 Zuni necklace surprises a viewer. By 1920 a Zuni conch shell pendant is inlaid with turquoise and jet.

In seven gorgeous examples of Zuni work in the gallery, a panel of text has been included which allows, “Zuni is complicated.” That’s an understatement.

I recently heard a story from an art gallery owner who said that the Zuni’s practice of “petit point”—beginning around 1920, Zuni lapidarists would set tiny, hand-cut stones, often hundreds of them, in a squash-blossom necklace—derived from the Zuni picking up the small chips of turquoise that would fly off Navajo smiths’ benches. The anecdote bespeaks the residual industriousness of jewelry makers.

Many of the cases in the Struever Gallery present objects made 30 to 50 years apart. One, for example, contains handwrought silver typical of 1900 and commercial sheet silver from the 1930s and 1950s. Yet the real stars of the show, and the place where the scholarship falls the most short, lies in the mid-century masters like the Navajo Tom Burnside and Austin Wilson and the Hopi Lewis Lomay and Charles Loloma. Their incredibly masterful intersections of jewelry and fashion took traditions way, way out on a limb, and were the precedents to head-to-toe fashions authored fully by Native designers.

Yet mainstream museums have come late to acknowledge that Native design in fashion merits front-row play, and are still reluctant to exhibit innovators outside of the context of tradition. One exception: The Peabody Essex Museum’s (PEM) bold Native Fashion Now, which opened last October, mixed up Native designers with European ones to manifest the constant intersections between popular culture and material culture in the Southwest.

PEM’s fashion survey claimed to be the first large-scale survey exhibition of Native American fashion in the US. On its heels comes this permanent exhibition of Southwestern jewelry which may be just one of two such museum commitments to jewelry—the other being the collection that Millicent Rogers collected in Taos and wore personally, now housed in the museum named after her.

What is great and what is imperfect about the Phillips Center lie therefore in close proximity as the world itself tends not to permit Native American artisans to emerge fully from the knot of tradition.

It is also a fact that the relationship of tradition to experiment can be an uneasy one in the present-day Southwest, best known for market events like Santa Fe’s annual Indian Market, where presentations both reflect the rule of practical economics—a jewelry maker’s livelihood for the year can be earned in the weekend—and the difficulties of being an exception. The organizers of Indian Market insist on strict definitions of traditional work that can be showcased at their event.

This traditional versus contemporary relationship is also awkward at the Phillips Center. When one reaches the epoch of the 1960s in the exhibit room, one gets an uneasy feeling that the curatorial effort to treat all periods of jewelry making as equivalent has managed to shortchange a huge breakout for Native Americans.

Preston Monongye was raised at Hotevilla at Hopi. His coral and turquoise pendant creates an abstracted naja that curves almost like an early Paloma Picasso design for Tiffany. Navajo Kenneth Begay’s handbag handle and ornament on a red leather purse beg the question of for whom he was working—a private commission, or a fashion collaboration?

There is only a minute amount of cast gold on display in this collection. Tufa-casting turns the use of high-karat golds such as those Charles Loloma used into a surface with a rough appearance that retains a closeness to expressions of earth even alongside the most refined lapidary imaginable. Loloma was to my mind the most brilliant and innovative of jewelers of the 20th century.

When it came to inlay, Loloma had no rival. He carved a coral plug into a badger paw and paved the inside of a 24-karat gold bracelet with lapis. The so-called “height bracelets” include an example here of silver and fossilized ivory, wood, coral, and turquoise. Tufa-cast rings from 1975 wrap metal around silver Pre-Columbian ceramic fragments. His work sizzled with curiosity and a refusal to be constrained. It also, in retrospect, reflects the difficulties of breaking out. When Loloma was flying his own airplanes and having models for Oleg Cassini sport his height bracelets on the Paris runway, being a Native person embraced by white European commerce was exciting, but it was confusing to his identity at home as a Native spiritual leader, according to sources who knew him.

This makes the paucity of explanatory text or historical information about what happened next all the more confusing. By today, one can easily assert that jewelry team Gail Bird and Yazzie Johnson continue what Loloma started—work that employs gold and precious stones for European tastes as well as Southwestern ones. Pat Pruitt brings to his latter-day jewelry a self-selection aspect in that the wearer has to be willing to sport weaponry in a part-Goth, part-Hell’s Angel aesthetic. Yet the fact that this center hosts only one “Designing with Metals” case and just one “Women Masters” case underscores how tough a job the curators may have had leaping from 1870 to now—from preservation and scholarship to “what the heck is going on?” wonderment. Can a study center be both historic and contemporary in heart and mind?

A close friend of mine who is a Navajo artist and brilliant wearer of jewelry compared the Phillips Center, not favorably, to a butterfly collection. I intuited that her fear was that the jewelry is presented as exotic, as lepidoptera, specimens of a lost world.

Could an alternative approach have been taken that would serve to manifest that contradictory things can simultaneously be true—and often are? All mastery relies first on a good teacher. Yet true fluency may be—and often is—throwing out the syntax of what you know.

It should go without saying that as in any tradition, Southwestern jewelry’s manifold influences are embossed and persistent. This gorgeous collection induces awe of the makers and their inventiveness.

Yet the “study” can’t entirely shrug off the strictures of anthropology to allow the heights and depths of innovation to show through. To simply be, as they are, both jewelry that belongs to a history and jewelry that departs from all attempts to give it a date-stamp and pin it down.

INDEX IMAGE: Charles Loloma, ring with badger paw, circa 1960, tufa-cast silver, 51 mm, photo: Jonathan Batkin

[1] Forty years later, in 1977, the Wheelwright became the first US museum to voluntarily repatriate from its collection two medicine bundles, cultural patrimony of the Navajo, back to the Navajo Nation.