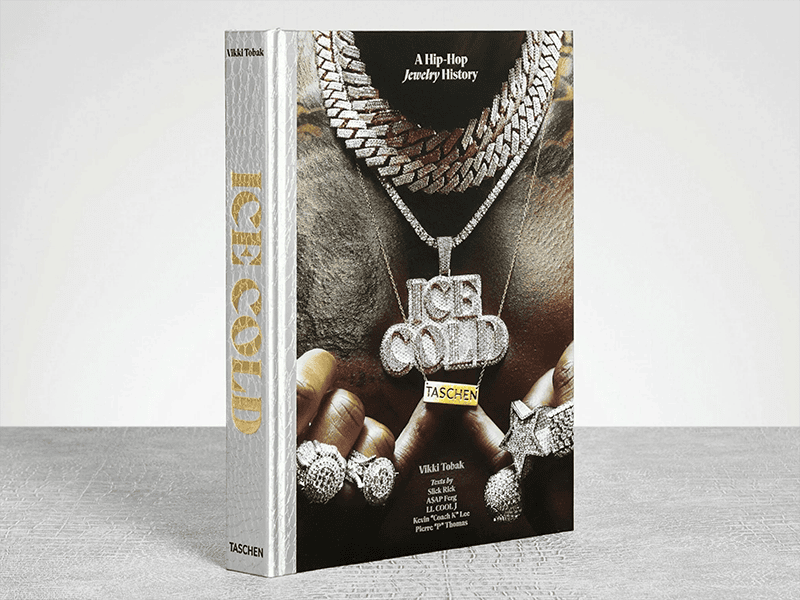

Vikki Tobak, Ice Cold: A Hip-Hop Jewelry History. Cologne: Taschen, 2022.

- This book is an excellent example of how jewelry and identity go hand in hand

- A related show, Ice Cold: An Exhibition Of Hip-Hop Jewelry, guest-curated by the book’s author, opened last week at the American Museum of Natural History, in NYC

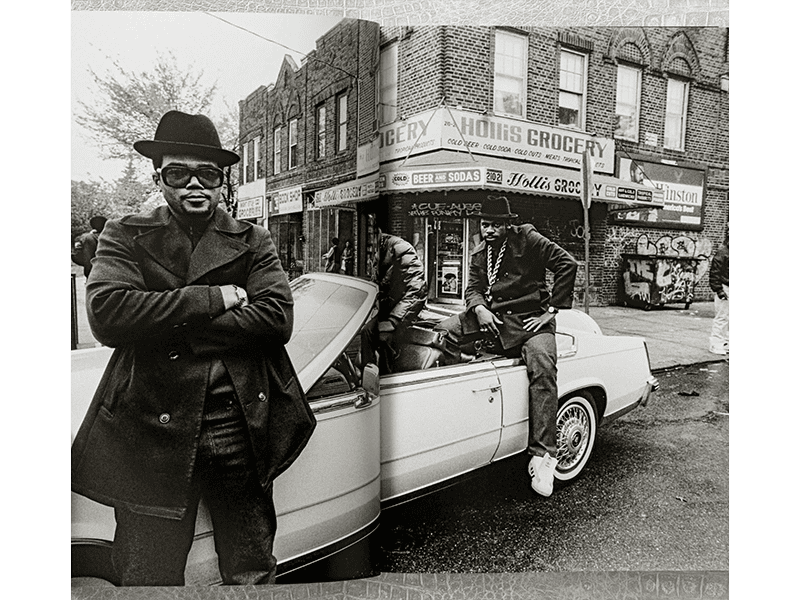

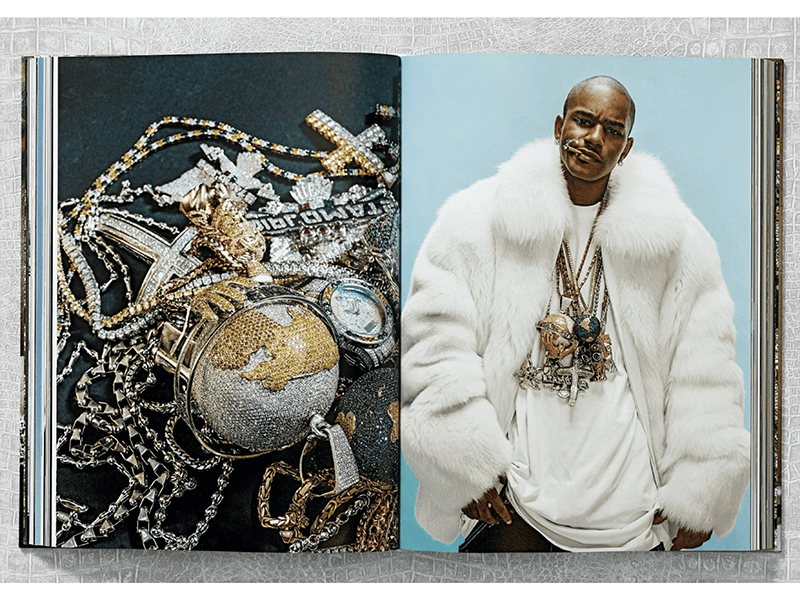

- It’s striking that, compared to other publications about jewelry, all the jewelry in this book is shown worn

The cover features a man’s chest. He wears a necklace with the title of the publication in pink diamonds: ICE COLD. Below that, the little fingers of his two lavishly ringed hands hold up a smaller necklace with a modest name tag bearing the book publisher’s name: TASCHEN. What brilliant graphic treatments!

The spine of the book has the texture of lizard skin, in silver. The endpapers look like images of treasures you’d see in children’s books or comics. So many diamonds and so much gold! It’s all grand, immodest, in your face, and a huge celebration, just like the rest of the book. Andy Disl did a great job with the design.

Everything is generous

Before the essays begin, the reader gets treated to various photo portraits. They are all full-page (the book measures 9.8 x 13.4 inches [24.9 x 34 cm]). The jewelry is clearly visible, whether it’s ear jewelry, rings, necklaces, watches, bracelets, grillz, or nails. This book weighs a few kilos (6.3 pounds) and is full of (historical) photos and information.

Compared to other publications about jewelry, it’s striking that the jewelry depicted is all worn. This is great, because a piece of jewelry is not meant to be viewed in splendid isolation. Jewelry is intended to convey (a message). This book is an excellent example of how jewelry and identity go hand in hand.

Not everything about the book is generous, however. The letters (white on black, and sometimes the other way around) could have been a little larger for ease of reading. But that’s no big deal. This book is more about paging through and looking at, although Vikki Tobak’s texts are well worth reading.

The jewelry regularly depicts Nefertiti. Christ with a crown of thorns, cartoon characters (including Bart Simpson), the Statue of Liberty, pistols, crowns, stars, astronauts, tanks, and the Mercedes Benz logo are also repeatedly portrayed. Mr. T makes an appearance, and Eminem as well: LL Cool J gifted him with a dookie rope (a large gold chain).

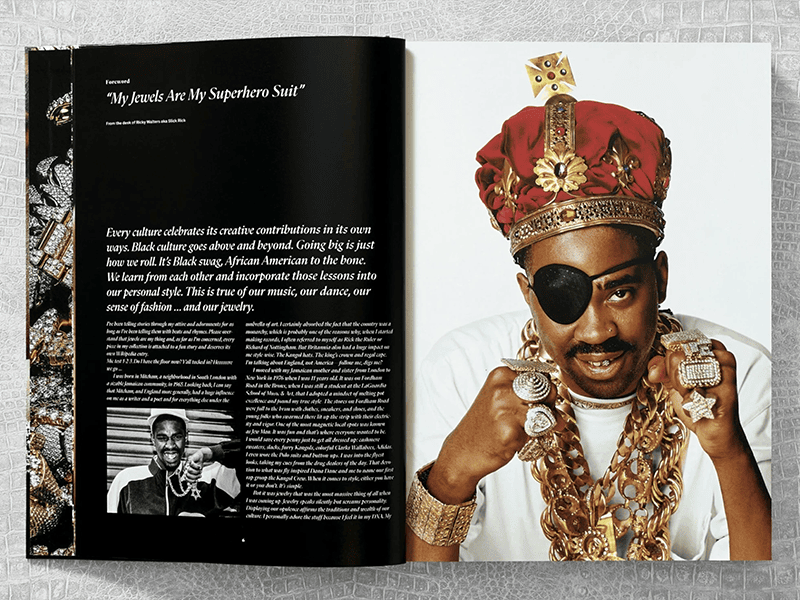

Slick Rick: my jewels are my superhero suit

The British-American rapper Slick Rick wrote the foreword. “I’ve been telling stories through my attire and adornments for as long as I’ve been telling them with beats and rhymes,” he states. “Please overstand [sic] that jewels are my thing and, as far as I’m concerned, every piece in my collection is attached to a fun story and deserves its own Wikipedia entry.” Another quote: “Jewelry speaks silently but screams personality.” Like a piece of jewelry, this speaks for itself.

After Slick Rick, fellow rapper and jewelry designer A$AP Ferg tells his story about his bond with jewelry. Then follows an introduction by journalist and curator Vikki Tobak, who experienced the development of the hip-hop scene from the inside. Originating from Kazakhstan, she ended up in Detroit as a five-year-old in the late 1970s. She was frowned upon by some white classmates—it was the Cold War—but warmly welcomed by the Black community. As a teenager, she moved to New York with her parents. There she went to work for Payday Records and became familiar with the hip-hop scene. She describes parallels between the jewelry of ancient Egypt, Africa, and contemporary America.

Drug dealers, hustlers, pimps, and the war on drugs

The style of jewelry in the hip-hop scene is originally derived from the jewelry worn by drug dealers and pimps. Their adornments lavishly showed their escape from poverty. The bigger the better! Mirroring the competitive nature of street culture, rivals regularly snatched the chains of hip-hop artists. The similarities between hip-hop jewelry and the jewelry of royalty and stars such as Elizabeth Taylor and Liberace are also examined in the book.

Much of the jewelry in the book is custom-made. Examples include the four-finger rings made of gold (and diamonds) with the text Billionaire Boys Club or Louis Eric Barrier. The book also pays attention to the misogynistic and deadly sides of the artists, the dealers, and the pimps. Many of them died of overdoses or drug-related violence.

Simultaneously with the rise of hip-hop culture, new laws were introduced in the US. The war on drugs resulted in mass incarceration. Black communities were disproportionately affected. Civil rights activist and writer Michelle Alexander described these laws as The New Jim Crow.

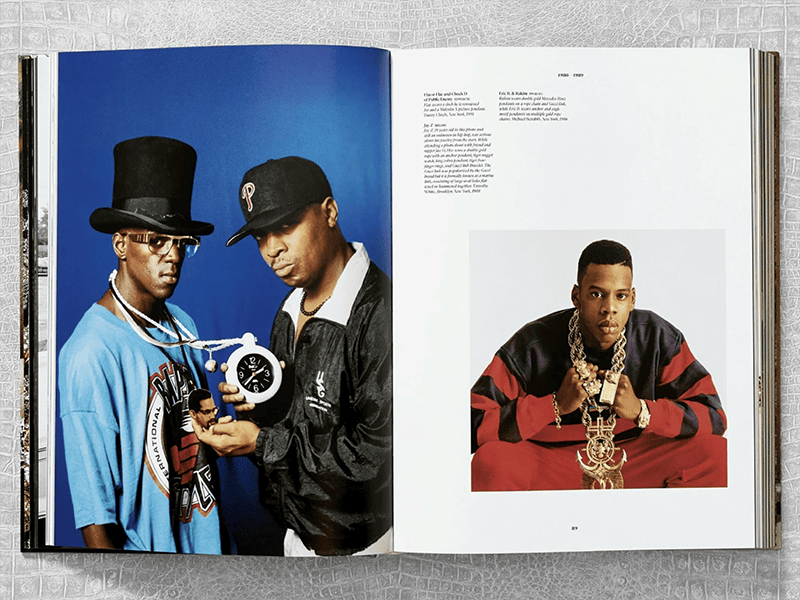

By the way, musicians don’t wear only gold or ice (diamonds). Some distinguish themselves with jewelry made of leather and beads. These include Queen Latifah, Public Enemy, Brand Nubian, A Tribe Called Quest, and De La Soul.

The introduction to the context of hip-hop jewelry is followed by four chapters. From the 1980s to the present, each decade is treated separately. Initially it’s mainly a male affair, but over time the number of women involved increases.

1980s

The chapter about the 80s, like the subsequent chapters, consists of a large number of photos with captions. Nameplates were widely worn in those days, as were stopwatches. The nameplates were not only worn around the neck, but also on the finger(s), on the hand, in the ears, or as belt buckles. They were often made of gold, sometimes iced—set with diamonds. Dookie ropes hung around the necks of many rappers. This jewelry celebrated identity and individuality.

1990s

Tobak describes how hip-hop evolved into a business model in the last decade of the twentieth century. Jewelry businesses evolved to supply the scene. “Ordinary” gold was exchanged for platinum, white gold, and diamonds. Jewelry was a vital part of any artist’s identity and marketing.

The world-famous high end jewelry houses ignored this new group of customers from the music scene. Most of the businesses who did serve the rapidly growing hip-hop market were immigrants from the Caribbean, the Soviet Union, or other parts of Asia. Many diamond traders, on the other hand, had fled from Antwerp, Belgium, as a result of World War II and were of Jewish descent, with networks in Tel Aviv and New York. In the 1990s, more and more people from India—a world center for mining and cutting stones—emerged as merchants.

Bling bling

In 1999, the term Bling Bling was coined from a song title on the Cash Money Millionaires album Chopper City in the Ghetto. It became widely known and ended up in the Oxford English Dictionary four years later (2003). Meanwhile, jewelry became increasingly larger. Record companies bound their artists and producers to loyalty with bling. The Roc-A-Fella chain (worth $100,000), commissioned by record label Roc-a-Fella Records and produced by Jacob the Jeweler (Jacob & Co), was presented with great ceremony to a select group of artists. The label Ruff Ryders gave R-shaped pendants with diamonds, again made by Jacob & Co, to Drag-On and Eve, among others. Death Row Records sported a macabre logo featuring a prisoner in an electric chair.

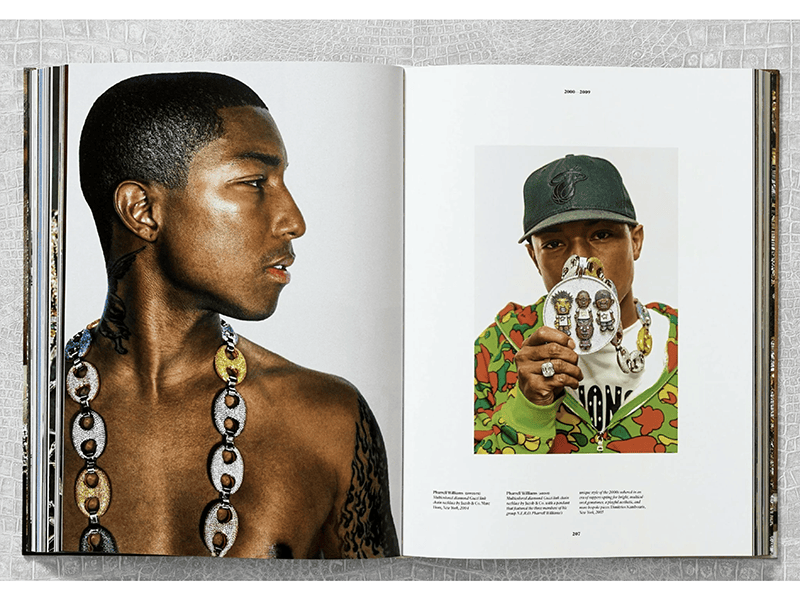

2000s

Hip-hop culture was not limited to New York. The regional differences are huge and get separate attention. The chapter about the first decade of the current century describes these regional diferences. Attention is also paid to the use of richly decorated chalices to drink from, another phenomenon revived by hip-hop artists. Don “Magic” Juan had one by Debbie the Glass Lady, and Snoop Dogg was seen with several specimens. Jacob & Co made a Rubik’s Cube and dice set with diamonds for the legendary Pharrell.

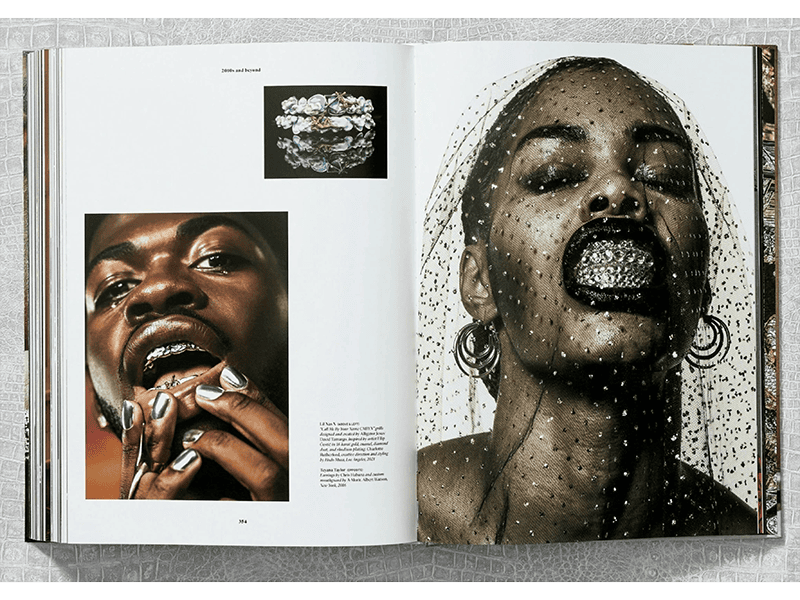

2010s and beyond

Black culture has unmistakably claimed its place in the realms of music, fashion, and bling. The time when gold and diamonds were unattainable for much of the Black community in the US is over. The new opulence has widely disseminated. Black people increasingly work for major luxury brands, those previously impenetrable white strongholds. Pharrell became creative director at Louis Vuitton in 2023.

Jewelry is also used to address social themes. The New York artist Azikiwe Mohammed created the work Unarmed in 2016. In it, a red board, like one in a jewelry store, shows 39 nameplates of unarmed Black people killed by American police in 2016.

By this time, bling is not only worn by rappers, but also by athletes such as Allen Iverson and LeBron James. Coach K, the co-founder and COO of Quality Control Music, says that he is the first in his family to break out of poverty: “… the South, where slavery was born in this country, we went from steel chains to diamond chains.” He also points out a painful difference between rappers and stars such as Liberace and Elizabeth Taylor. Neither Taylor nor Liberace were ever asked where the money for their jewelry came from.

Finally, Black jewelry designers and Black jewelers are also becoming active, and more women are appearing on the jewelry scene, too. Jewelry has become more colorful in the past decade. Previously, mainly colorless diamonds were processed, but now they’re used in all kinds of colors. It’s also striking to see in the photographs in the last chapter that faces are being tattooed more and more often.

One of the last spreads in the final chapter shows Rihanna wearing an ear cuff by jewelry designer Lynn Ban. This is followed by a conversation with two producers about the meaning they attach to jewelry. And there’s an index at the end: another quality feature!

Unlike almost all other literature on jewelry, this book shows the relationship between jewelry and its wearers. There’s some catching up to do when it comes to publishing literature on Black (popular) culture. This volume is a big step in that direction. The book is nowhere modest. Just like the jewelry, the book is grand.

Reviews are the opinions of the authors alone, and do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org