Hand + Made is the catalog for the 2010 exhibition of the same name, curated by Valerie Cassel Oliver at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston. The publication features essays by Oliver, Glenn Adamson, and Namita Gupta Wiggers, along with rigorous catalog entries by Sarah G Cassidy. Both the book and the exhibition seek to explore the critical content and performative potential behind the making process and to delve into the conceptual power of contemporary craft.

In the first essay, ‘Craft Out of Action,’ Valerie Cassel Oliver draws a brief history of the performance in craft, from the Bauhaus to the studio craft movement and beyond. She ends by claiming that craft is a field rife with potential for reinvention; it is ‘no longer relegated to the binary of functionality and autonomy.’ Glen Adamson’s essay, ‘Perpetual Motion,’ focuses on the trouble of conspicuous skill, claiming that oftentimes ‘craft objects do not transcend the skill that went into their making.’ Adamson presents the work in the exhibition as a ‘reimagination of the relation between performance and object,’ freeing craft from its reliance on displays of virtuosity and the necessity to produce functional objects. Elaborating on Adamson’s statements about the future of craft, Namita Gupta Wiggers considers an expansive definition of the scope of craft in her essay ‘Craft Performs,’ suggesting that ‘by focusing on spaces, places, and ways in which visual practitioners perform craft today, we can enhance our understanding of the easily overlooked craftscape.’ Throughout her essay, Wiggers also touches on the moral value of the handmade, specifically in her references to the DIY movement and the work of artist Gabriel Craig.

While the essayists are eager to consider the performative potential in both art and craft, their premise is slightly disingenuous; much of the work seems ill-at-ease in this exhibition, chafing from the friction between the words ‘art’ and ‘craft’ pressed so tightly together in the title. The most salient points of this exhibition are those moments where the future of craft is considered in its own language and history, without any attempt to equate craft with art. There is a vague sense that this catalog was assembled with the hope of mapping out performance in craft on a one-to-one scale with the last century’s development of performance art. This is a mistake and evidence that we are building our future upon an unsteady foundation. How can we continue to work in a field that is constantly disavowing its own claims to an independent existence? Is craft different than art? If it is, then why do we insist on speaking as though it were not? The answer to this question must be that craft is different. There are certain things that craft does better than any other field, such as a close consideration of function.

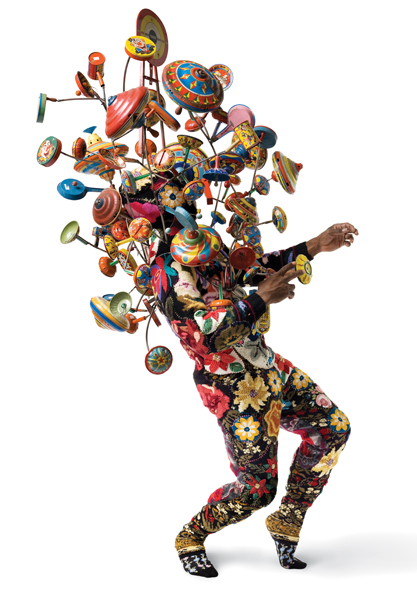

The artists in Hand + Made are not content to let their work hang on a wall or sit on a pedestal; they seek active engagement. Oliver dubs this impulse towards interactivity ‘performativity,’ but a more accurate term would be ‘performed use.’ While the essayists seem eager to unshackle craft from its associations with function and the functional object, this is something that clearly sets craft apart and as such, should be celebrated. The unique purview of craft lies not in the performativity of process, but in the performativity of use. Disappointingly, the essayists seem to center their focus on the process of making rather than on the performative potential of the finished object. Adamson goes so far as to suggest that the object may not hold a central role in the future of craft, remarking that, for the work in Hand + Made, ‘the process is the product.’

Take Yuka Otani’s Sweet Vessels as an example. It is through their use as tableware that these delicate goblets of hand-blown sugar will slowly decompose. Their physical presence and their ability to operate as functional objects is not at all incidental to their performative potential as Adamson seems to suggest. Rather, it is vital to the work’s conceptual success. Sweet Vessels live in their function. The importance of the object can also be seen in work where the object itself is completely destroyed, as in Ryan Gothrup’s Diversion. In this piece, Gothrup took several hand-blown glass basketballs to a neighborhood basketball court to shoot some hoops. The balls were expertly crafted to look identical to their mass-produced rubber counterparts and it is only when they shatter on the pavement or against the hoop that their material is revealed. As in Sweet Vessels, it is this work’s performed use that fully activates its potential.

The essayists in Hand + Made challenge us to imagine craft beyond the object, while the artists invite us to give the object another look. The theory, in this case, does not seem to agree with the practice. And while I applaud Adamson’s assertion that virtuosity is not enough to justify our critical interest in the craft object, the performance of process is not enough to override the importance of the object to the field, either. As a collection of individual essays and works of art, Hand + Made presents a compelling series of possibilities for the future of craft, even if those possibilities are often at odds with one another.