Radiant Pavilion – Melbourne Contemporary Jewellery and Object Trail

September 1-6, 2015

Melbourne, Australia

A new jewelry festival has arrived with great expectations and significant challenges. How can a “Schmuck of the South” emerge from the shadow of the more established original in the north? What is its point of difference? How will it advance the global contemporary jewelry scene?

Organized by Claire McArdle and Chloë Powell, this first Radiant Pavilion (another is being planned) was a festival involving 57 exhibitions, tours, and public installations drawing on Melbourne’s extensive network of jewelry galleries.

The scale itself was testament to the festival’s initial success and one review can’t do justice to all the exhibitions. So I set my critical framework by the title, focusing on elements that relate to the festival concept rather than those exhibitions that could have happened normally.

According to the organizers, the title Radiant Pavilion creates “a point from which contemporary jewelry and object could radiate outwards.” This particular outward momentum has many semantic layers. Jewelry-wise, it refers to a gemstone cut (“radiant”) and the base of a faceted stone (“pavilion”). Art-wise, it evokes art festivals in public spaces, such as the Venice Biennale. And literature-wise, the phrase “radiant pavilion” appears in the Arthurian epic Perceforest as the title for a parade of nobles assembled for a grand feast—“the pavilion was filled with such a light that the images and friezes woven into its side glowed out to the beholders like pictures in stained glass.”[1] As a title for a festival, it sparkles.

Many individual components lived up to expectations of splendor. The People’s Prize winner, Anna Davern’s The Golden Land of the Sunny South, at e.g.etal, was an intricately carved diorama containing a fanciful antipodean history of settlement. While most contemporary accounts depict Europeans as violent invaders of the land, this scene presented noble settlers persecuted by invading kittens—a reference to the tyranny of Facebook?

Many individual components lived up to expectations of splendor. The People’s Prize winner, Anna Davern’s The Golden Land of the Sunny South, at e.g.etal, was an intricately carved diorama containing a fanciful antipodean history of settlement. While most contemporary accounts depict Europeans as violent invaders of the land, this scene presented noble settlers persecuted by invading kittens—a reference to the tyranny of Facebook?

As a narrative, the diorama harkened back to Davern’s iconic Intervention exhibition (2006): the works on show were made of biscuit tin lid from which the tokenistic[2] Aboriginal figures had been cut away, hinting at the erasure of indigenous peoples during colonization. The absence of Aboriginal figures from this latest colonial diorama prompted similar thoughts. What was initially diverting entertainment became, on reflection, oddly disturbing.

The diorama was also notable on a formal level. Since the beginning of her career, Davern has created stands for her jewelry that are sometimes even more elaborate than the rings they hold. In this case, the jewels were attached to characters in the drama. Removing a kitty brooch can reveal the knight hidden behind the mask. Davern opens up a new way of animating jewelry.

The festive theme was continued by the co-coordinator herself, the mercurial Claire McArdle. The works in Oaxaca Experiencia employed hojalata (hammered tin) and embroidery techniques learned in Mexico. The exhibition worked well as an immersive carnival, though McArdle had set the bar high for herself in previous shows where visitors have tried on false beards, worn masks, or even eaten the works on display. We weren’t so challenged in this case.

There were occasional references to politics among the programmed exhibitions. In Penny Jagiello’s Melt, Future Remains, jewelry from plastic flotsam was exhibited in frozen blocks of ice, the baubles gradually revealed under the influence of warm spring breezes. Also notable was Meet Me, by Minna Loft, an impressive series of collaborations with craftspersons from the global south.

But a jewelry festival needs to be more than a feast of exhibitions. Within the framework of a city-wide event, can jewelry tempt a mostly Anglo population to indulge in gratuitous acts of ornament? Melbourne is well suited to realize this potential. The city is distinguished by its capillary system of laneways, which host secretive bars, stencil art, and bespoke galleries. Such spaces lend themselves to the arresting moments of intimacy triggered by jewelry.

There is one lane in particular that epitomizes this promise. Almost all of Crossley Street was taken up with jewelry events. On show at Gallery Funaki were new works by Warwick Freeman: the austerity of PRIME contrasted with the playful nature of the rest of the festival, suggesting an elder confident enough to return to basics. Down the lane, Gray Street Workshop had taken over a space for the impressive group show Theatre of Detail. Jess Dare interpreted the Thai garland using birthday candles that evoked a new East-West hybrid ritual. A more abstract decoration was found in Sue Lorraine’s elemental Models of Light. And Catherine Truman’s video of a plastic glove dissection carried her interest in the anatomy of the hand into new theatrical dimensions.

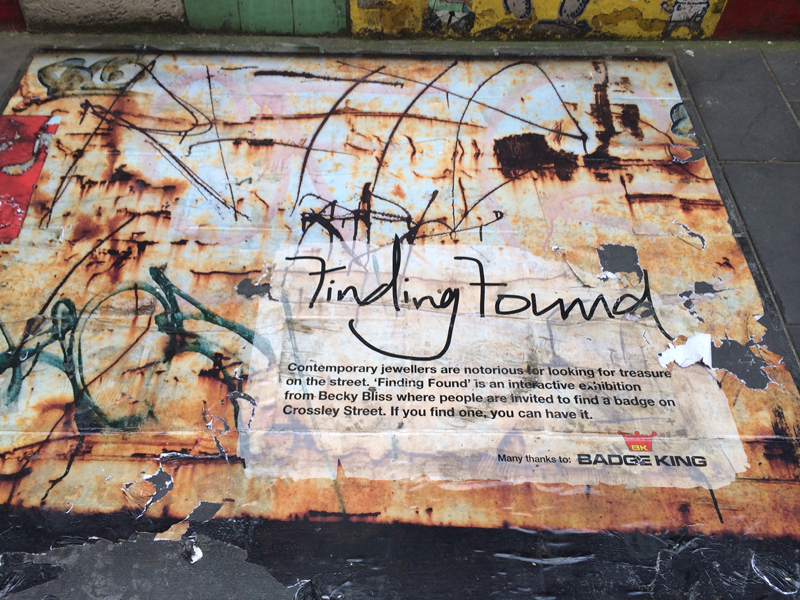

Other shops along Crossley Street were occupied by works from New Zealand artists. I was reminded of the legendary Cuckoo collective, another group of artists from across the Tasman that existed without money by occupying gallery spaces during down time. Becky Bliss created a stir by scattering her works along the street during the day, including some brooches on rubbish bins.

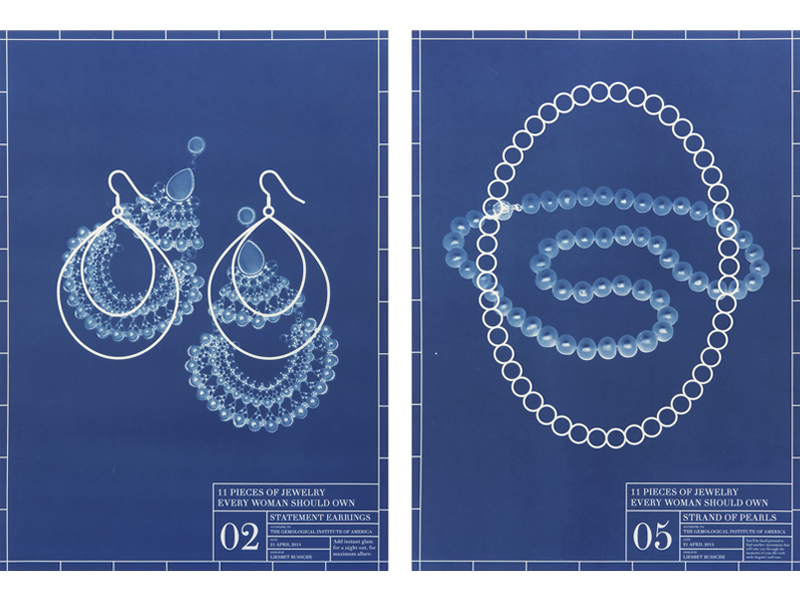

Outdoor installations were activated by walking tours. Site 3065: South-East Corner was installed along a route through lanes and shops in the suburb of Fitzroy. I was particularly struck by the generosity of the participants. Co-curator Manon van Kouswijk distributed a publication documenting jeweled cityscapes, Benjamin Lignel provided posters for public declarations of love, and Susan Cohn handed out badges welcoming alternative genders. This gift economy tested our private ownership of jewelry. At one stage, participants were asked to exchange personal jewelry items. Later, a popular vote was held in response to Liesbet Bussche’s Eleven Pieces of Jewelry Every Woman Should Own (According to the Gemological Institute of America).

The tour ended with co-curator Roseanne Bartley’s My Shadow Wears, an Instagram-based work where participants photograph incidental objects framed by their body. This work builds on her classic Barcelona piece Human Necklace, where she used the camera to create a conceptual work of jewelry. Her 2004 photograph of dancers in a public square appropriated incidental elements like a ball into an ornamental arrangement. The current work adds to this practice a participatory process that she has developed from subsequent projects like Seeding the Cloud.

Inari Kiuru and Nadine Treister also developed an ambulatory exhibition. The Shining was located around a train station aptly named Jewell, in the suburb of Brunswick. Items spray-painted in gold evoked the origins of the suburb as a launching place for the gold fields of Victoria during the 1850s.

Occasionally, the indoor and outdoor elements were combined. One of the most resolved exhibitions was the Taiwanese group show Inner Crease. Achingly delicate works were housed in a public bar associated with rituals of Australian male camaraderie. Ying-Hsiu Chen’s objects evoked sea urchins. Yu-Fang Chi’s Sensory Crease pieces were finely woven in silver wire (from a recent residency at the Australian Tapestry Workshop). Yung-huei Chao’s Rooftop Series rendered architectural cladding in delicate craftsmanship. Though incidental, the video promoting the show poetically located the works in the ramshackle gray Taipei cityscape.

Having been an audience member of the Melbourne scene for more than two decades, I couldn’t help but feel odd moments of déjà vu. Previously, Caz Guiney has not only made jewelry out of ice (1998), but also placed precious works in public spaces as part of City Rings (2003). Groups like Part B have also generated a history of public jewelry art in Melbourne laneways. I felt the need to work harder to record ephemeral jewelry performances on the street. By contrast with exhibition works, they are rarely accompanied by the professional photography and catalog essays that are necessary for entry into jewelry history archives. Without this record, street works can end up being repeated rather than built upon.

Having been an audience member of the Melbourne scene for more than two decades, I couldn’t help but feel odd moments of déjà vu. Previously, Caz Guiney has not only made jewelry out of ice (1998), but also placed precious works in public spaces as part of City Rings (2003). Groups like Part B have also generated a history of public jewelry art in Melbourne laneways. I felt the need to work harder to record ephemeral jewelry performances on the street. By contrast with exhibition works, they are rarely accompanied by the professional photography and catalog essays that are necessary for entry into jewelry history archives. Without this record, street works can end up being repeated rather than built upon.

Given her groundbreaking work in the social dimension of jewelry, I was especially interested in Susan Cohn’s show UNcommon moments at Anna Schwartz Gallery. The exhibition felt unsettling even before catching sight of the works. An aluminum walkway stretched the length of the gallery. But to inspect the works, you had to abandon the boardwalk and walk over a bare concrete floor. This implied act of transgression framed the works with a sense of precariousness.

We moved through three distinct scenes—leaving, arriving, and staying on. The first featured a small pine box containing metal tags. The large video projection showed Susan Cohn and another women washing the body of a corpse. The tags appeared to be messages for the grave, such as “Your secret is safe with me.” It was unclear whose secret it was—the dying or the living. At her artist talk, Cohn spoke about the creative collaboration with a terminally ill colleague, the glass artist Ian Mowbray. In an “uncommon” moment, after confessing that neither of them expected that he would still be alive by the time of the exhibition, she acknowledged his presence in the audience. The odd second of silence that followed demonstrated a jeweler’s courage in dealing with moments of great intimacy.

Arriving consisted of pendants, including memory sticks, hung from an impersonal metal mesh. These faced a sea made from shredded newspapers, hinting at the confusing flow of information that must be navigated by refugees. Finally, Staying On featured objects of persistence, such as a reset button pin, a finely wrought mesh bowl that is testament to Cohn’s own perseverance, and napkins embroidered with “Let’s start again.”

While I was excited to see another chapter unfold in Cohn’s career, its presence in Radiant Pavilion raised some issues. Confined in the gallery, UNcommon moments wasn’t able to fully activate its possibilities—where were the refugees to receive the message sticks? This mirrored the limits of Radiant Pavilion, which could have used the relational potential of jewelry to connect with the public. While the contemporary jewelry world is vibrant enough on its own to support a festival, engaging outsiders has potential to fulfill the work’s implied social ambition.

There is still so much of the festival dimension in jewelry yet to be realized. There was a hint of this at the public workshops in jewelry-making from recycled materials offered by Ethical Makers Movement. It would be amazing to see a project like UNcommon moments extend into the street. Private jewelry tours could evolve into the kinds of public parades covered by Lizzie Atkins in AJF’s Show and Tell.

And given the potential to be the “Schmuck of the South,” it would be stimulating to build lateral connections across the region. Ironically, Radiant Pavilion coincided with the equivalent event for South America, En Construcción in Valparaíso, Chile. But their common ground stretched only as far as New Zealand. While Lisa Walker went east to hold a workshop for the South Americans, others from Wellington flew west to Melbourne. Hopefully next time the two continents will connect up in a trans-Pacific dialogue, adding fresh perspectives on the street, indigeneity, politics, and tradition to the global contemporary jewelry scene.

This first Radiant Pavilion proved that a jewelry festival could gather city-wide support and be enlivened by the generous and fulsome participation of artists. The second, now in planning phase, has potential to build on this and establish itself as an iconic, splendid, and radical fixture in the global jewelry calendar. Something glimmers on the horizon.

[1] Nigel Bryant, Perceforest: The Prehistory of King Arthur’s Britain (Suffolk, UK: DS Brewer, 2011), 417.