Unique by Design: Contemporary Jewelry in the Donna Schneier Collection

May 13–August 31, 2014

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A collection always bears its own narrative. This narrative is usually inspired by a folksy story about the first acquisition, a heralded inaugural object that serves as a kind of synecdoche that characterizes and sets the tone of the collection as a whole—not only in terms of the object’s art-historical significance and provenance, but also through the story itself, which details in some lyrical way the epiphany that sparked the collector’s zeal. Reflexively, the collector often views the gathering of works as a form of self-expression. This Romantic perception of collecting shapes our expectations, such that when we visit an exhibition of a collector’s treasures, along with viewing the individual works we also want to understand something about the collector’s humanity, inspiration, and perhaps also the wealth that allows such passions to be nurtured and indulged.

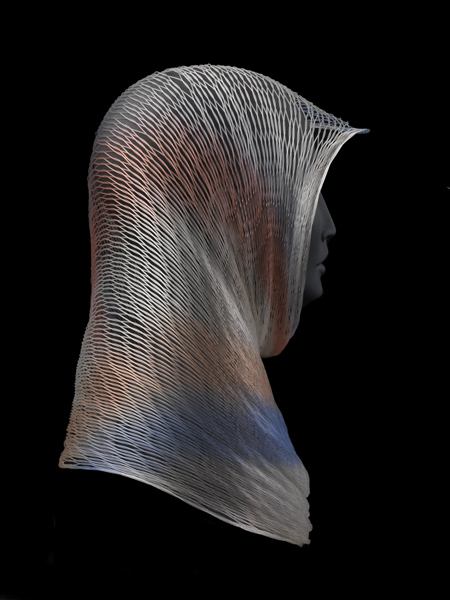

Donna Schneier came to the field of contemporary jewelry in 1985, when—at the British Crafts Centre in London—she chanced upon a work that would become her first purchase: Caroline Broadhead’s Veil Collar, 1983[3] (now in the Museum of Arts & Design’s holdings as part of the 1997 gift of contemporary jewelry in nonprecious materials, exhibited in 2002 under the title Zero Karat: Jewelry from the Donna Schneier Collection). It is well documented that Schneier, educated in art history, ran a business selling commercial jewelry; her encounter with singular jewelry pieces that were wearable yet crossed into the territory of autonomous artworks sparked a passion that eventuated into the collection of some 600 pieces. A selection of this collection, executed exclusively in nonprecious materials, went to the Museum of Arts & Design (as mentioned above). As Schneier added to her collection, broadening her focus to include works in more traditional materials, she made a contribution to the Met beginning in 2007 and continuing to the present day; a third group, consisting of some 50 works in both valuable and nonprecious materials, went to the Racine Art Museum in the same year.

Unique by Design celebrates Schneier’s gift with a presentation of some 80 works, out of the 132[4] gifted by Schneier and her husband, Leonard Goldberg. The collection is a survey of contemporary jewelry from 1960 to the present. The exhibition is installed in the Met’s Gallery 909, which, according to exhibition curator (and caretaker of the collection) Jane Adlin, is host to exhibitions of works from the museum’s collection of modern and contemporary decorative arts and design.[5] The intimate dimensions of the gallery, scaled for the presentation of objects, is proportioned beautifully to the collection of works on view.

Deep gray walls and focused spot lighting heighten the drama of the objects on display, which are housed in seven free-standing glass vitrines, arranged in rows, set atop metal supports at a height of around 90 cm to 2 meters, which facilitates viewing of the works in an ideal way and at a sympathetic height that requires no bending or peering.[6] Inside the vitrines, the works are mounted on white platforms that catch and bounce the light from overhead; whenever possible, they are suspended above rather than set on the platform surfaces. This generates an energy and tension while showing the pieces from every angle and to their best advantage. The number of pieces in each vitrine is limited, creating habitats in which the works are allowed space to breathe, but they also enjoy a close proximity that allows for conversations that generate added context. Certain pieces especially benefit from the installation, which not only offers a 360-degree view but also demands a look at the backs of the pieces. The determined and cheeky placement of labels on the opposite side of the vitrines, contrary to the exhibition’s flow, belabors this point, and most viewers during my visit seemed to find it disingenuous. Whatever your feelings about the placement of the labels, I find it difficult to imagine a situation in which—amid these spacious glass boxes, illuminated in the darkened gallery—a viewer would not bother to view the work from the opposite side, especially given the orientation of a few, select works (among them pieces by Earl Pardon and Eunmi Chin). In any event, the invitation to meaningfully observe the works from the back side allows a deeper understanding of contemporary jewelry, which often incorporates challenges to hierarchies of “front” and “back” in its repertoire of critical and dialectical concerns.

The works on view in Unique by Design, spanning a period of some 50 years, perform in unison to produce a fairly balanced and straightforward account of contemporary jewelry as seen today. The presentation, while not chronological, does allow for the contemplation of the field’s development (or lack thereof); the rejection of precious materials in the 1960s to 1980s; and subsequent return to their use in the 1990s to the present.

Positioned at the entrance of the gallery and thus setting a tone for the exhibition is a small vitrine displaying Eugene Pijanowski and Hiroko Sato-Pijanowski’s luminous Oh I Am Precious #7 (1986). The bipartite neckpiece beckons with the luxuriance of 24-karat gold, yet closer inspection reveals the use of ordinary paper cord applied meticulously to a canvas support, voicing contemporary jewelry’s claims to value without regard to the rare metals that characterize traditional jewelry practice.

In addition to Künzli’s work, the “Minimal” vitrine offers a grouping that represents concerns such as “pure shapes and monochromatic surfaces … lack of narrative or anecdotal content and use of pared-down design elements.” Alyssa Dee Kraus’s silver necklace, titled I Sing the Body Electric (1998); Joan Parcher’s Mica Chain (1994), made from mica and silver; and Giampaolo Babetto’s 18-karat-gold-and-synthetic-resin Anello da Mignolo (Ring for Little Finger) (1983), tell a slightly different story of contemporary jewelry’s relationship with Minimalism, one that has more to do with formalism than concept.

The exhibition’s presentation of works in gold spotlights contemporary jewelers who choose to return to this decidedly traditional material to execute forms that are not always traditional, aligning closely to works in the artist’s oeuvre executed in less valuable materials. Mary Lee Hu and Lisa Gralnick are known for their frequent use of gold, however, and their exquisite manipulations of the material are highlighted to effect here; likewise, Myra Mimlitsch-Gray’s Brass Knuckles (1993) is a tantalizing expression in 24-karat gold of bravado and bling, and Hermann Jünger’s sumptuous brooch, a composition of 18-karat gold and a wealth of gemstones such as emeralds, sapphires, and lapis lazuli (circa 1970–1972), is a radiant piece of eye candy (although the high placement of pieces by Jünger, Gralnick, and Hiramatsu Yazuki seemed a bit too out of reach for this height-challenged viewer).

The vitrine dedicated to “Found and Parodied Objects” presents works by Helen Britton, Bob Ebendorf, Ted Noten, and the late Ramona Solberg, among other artists who consistently work with nonprecious materials and objets trouvés. Noten’s Fashionista necklace (2009) is a wearable chain of nine different stiletto shoes, an homage to the fêted status occupied by the shoe in the realm of women’s fashion. In Fashionista, Noten creates a rarified portrait of the shoe and treats it as a jewel, removing it from the foot, much as works of contemporary jewelry are removed from the body to be shown in the gallery—a critical touch that runs throughout much of Noten’s work.

In addition to (and in no way overshadowed by) the works in the vitrines, cases dedicated to the display of multiple works by three artists—Thomas Gentille, William Harper, and David Watkins—are mounted on the wall as one enters the space. The highlighted presentation of these veterans provides an anchor to an examination of the field overall, while allowing a closer look into the ways these artists engage in lengthy investigations, often producing large numbers of works aimed at honing and perfecting an idea, technique, surface, form, or connection to the body—components that serve contemporary jewelry’s patron disciplines of art, craft, and design. The decision to extend the presentation of select artists’ works is an intelligent one, and contributes to the overall presentation an element of the process that remains so crucial in the discourse of contemporary jewelry and, by extension, contemporary craft.

Because the works in the exhibition (and in Schneier’s collection) are, for the most part, one-of-a-kind, the choice of Unique by Design for the title is on the one hand pithy and oxymoronic, but on the other it does encourage audiences to consider the contemporary jewelry question in a nuanced way that the texts and contextualizations—with their art–historical focus—do not.

But Schneier’s collection does have a balance that lends itself easily to a survey of the field, and as such, the curatorial markers seem to be applied in moderation. Taken as a whole, the works presented in Unique by Design form a collection that stands as an historical presentation of contemporary jewelry from the 1960s on, attesting to the vision and savvy of a focused, systematic collector. The works on view tell a story of 50 years of contemporary jewelry, showing an engagement with materials, creative inspiration, and some challenge to convention, but demonstrating little paradigmatic shift overall. Represented here is a solid and fairly orthodox collection—you won’t find any conceptual or non-wearable pieces here, and as such your thirst for more challenging works will have to be satisfied elsewhere (for example, at the Multiple Exposures exhibition on view now at the Museum of Arts & Design). However, the exhibition serves audiences well, including those already familiar with the tropes and arguments circulating in contemporary jewelry, as well as the uninitiated, who can find much to admire in the myriad works displaying rich content, surprising and beautiful forms, and high levels of craftsmanship.

Index Image: Exhibition view, Unique by Design: Contemporary Jewelry in the Donna Schneier Collection, 2014, foreground work by Myra Mimlitsch-Gray, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, photo: Jennifer Navva Milliken

[1] Jean Baudrillard, “The Non-functional System, or Subjective Discourse,” in The System of Objects, trans. James Benedict (London: Verso Books, 1996), 91–92.

[2] Baudrillard, 94–95.

[3] Toni Greenbaum, “Possessed: Donna Schneier,” Metalsmith, 34, no. 3 (2014): 22.

[4] Suzanne Ramljak, Unique by Design: Contemporary Jewelry in the Donna Schneier Collection, exhibition catalog (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014), 11.

[5] From an email with Jane Adlin, Associate Curator for Design and Architecture in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, received on June 20, 2014.

[6] When displaying works of art, conditions such as placement, scale, spacing, and—perhaps most critical—lighting are carefully considered. Objects are inherently three-dimensional and should be presented with optimal visibility, from all sides. Precious and fragile materials necessitate vitrines—the bane of museum curators concerned with maximizing visitor access to the works—and the question becomes: “How can we present the object in its best light despite its being behind glass?”

[7] Now held by The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

[8] Baudrillard, 105.