Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line

September 19, 2021–January 2, 2022

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, US

A successful retrospective exhibition feels like an immersive experience. The visitor should almost get the impression of traveling in a time machine. There’s a certain magnificence in viewing so much of an artist’s body of work in one place and seeing its evolution over the course of their life. It’s also exciting to gain new understandings of that artist’s process in a unique way that’s only possible by seeing these objects together in person. What characteristics become the defining constants of their work? Which concepts were chosen for iterative exploration? How did echoes of abandoned ideas subconsciously become present in later work? Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line, at the Walters Art Museum, is Cooke’s first comprehensive retrospective. It checks all these boxes, taking visitors on a journey through time that chronicles the career of one of the most respected and prolific American jewelry designers.

Betty Cooke, a lifelong Baltimorean, began her career in the 1940s following her graduation from the Maryland Institute of Art. (It’s now called the Maryland Institute College of Art, or MICA.). She opened her first shop and studio on Tyson Street, just a few blocks away from the Walters. In 1965, Cooke moved her business to the Village at Cross Keys, a boutique shopping center in northern Baltimore. She opened a store there called The Store Ltd. To this day, she continues to sell her jewelry there alongside other craft accessories, apparel, and various high-end gifts.

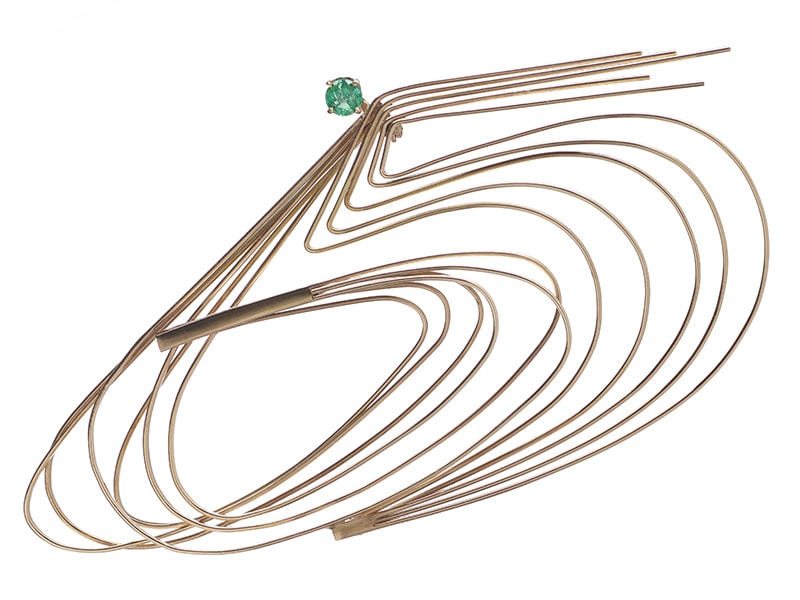

It didn’t take long for Cooke to gain national recognition for her clean, minimalistic designs that made use of simple shapes, most notably circles and lines. While circles and lines themselves are simple, Cooke’s designs are anything but.

The neckpiece selected as the centerpiece of this exhibition is a perfect example. It consists of repeating patterns of three or four circles inlaid between straight lines, arranged asymmetrically and in such a way that the individual circles and lines are not immediately seen. Instead, it appears as an abstract shape resembling a supernova. At the beginning of the exhibition is a quote by Cooke: “When I taught, we used to study what can be done with one straight line. I can spend years with a circle. If you have the ideas and the materials, the results are limitless.” This is not hyperbole. The pieces in this retrospective are evidence that for Cooke, a circle is one of infinite starting points.

Upon entering the exhibition space, visitors are greeted by wall panels that introduce Cooke as a maker. They also describe the Good Design movement within the mid-century modern era. Cooke frequented the Walters Art Museum as a child and later drew inspiration from many objects in the museum’s collection, some of which are on display here as part of this exhibition. Upon my realization that these very pieces directly influenced Cooke’s work, the retrospective took on a new sense of intimacy, as though I were being treated to a behind-the-scenes glimpse into Cooke’s design processes and personal inspiration.

One particular display case contains a German gauntlet (1525–1575) and an Islamic breastplate (1700s) side by side with five of Cooke’s pieces: two rings, two pins, and a neckpiece dating between 1960 to 1993. All feature a marriage of metals. The armor is made from steel, copper alloy, and gold, while Cooke’s jewelry is fabricated from silver, brass, and gold. Each piece of jewelry feels as though it could be a small piece of modern-day armor, giving its wearer a sense of confidence and security. This is especially true of the two pins, as their shapes (one round, one square) call to mind the traditional shapes of shields.

Approximately 160 objects are on display within this exhibition. Indeed, the sheer volume with which visitors are met is impressive in and of itself. Despite the recurring circles and lines, all of Cooke’s pieces are incredibly—almost inexplicably—unique. Where many artists might struggle to repeatedly push their work in a forward direction, Cooke does so with the ease of turning on a faucet. Every piece feels as though it gave birth to the next. Even though they share basic characteristics, they’re exquisitely their own entity.

Each case has been laid out with careful attention to its visual landscape. Objects appear to have been grouped based on theme, materials, and other commonalities. Some cases contain pieces that are clearly part of the same series, while others hold pieces made decades apart. At first I found this strategy confusing, given the exhibition’s emphasis on chronology as demonstrated by its narrative and spatial design. Upon further reflection, however, I recalled Cooke’s quote regarding the infinite possibilities of a circle. Perhaps that is what the exhibition is trying to demonstrate on a microcosmic level. Here is Cooke, continuing her exploration of a specific element over the course of 10, 20, or even 30 years, like a jeweler’s version of the theme and variation motif in classical music.

It’s evident that a lot of thought went into the visual components of this exhibition. The walls have been painted with muted pastels that change from room to room to signal that visitors are entering a new decade of Cooke’s career. Additionally, giant outlines and silhouettes taken directly from Cooke’s jewelry adorn larger wall sections, painted in a solid color a few shades lighter or darker than the wall itself. This could have easily felt heavy-handed and overwhelming. However, maintaining a monochromatic scheme contributes to the ambiance without distracting from the work or story on display. These wall graphics heighten the sense of being immersed into Cooke’s world as an active observer, and are perhaps a testament to the endurance and adaptability of Cooke’s designs. Important text is highlighted by marigold borders, immediately capturing visitors’ eyes and inviting them to read about milestones from Cooke’s career.

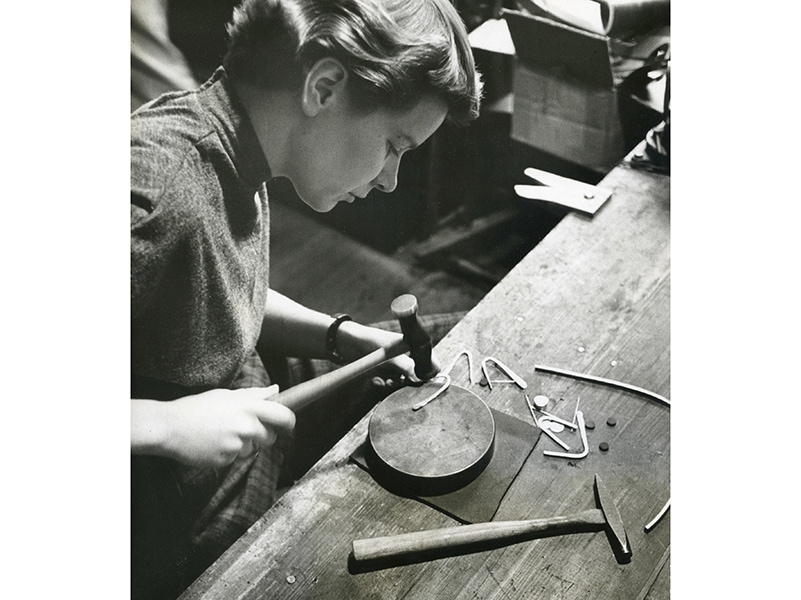

A mock jeweler’s bench has been set up midway through the exhibition to give insight into how Cooke’s pieces are made. Common tools are displayed, with labels explaining how they are used, and the significance of the bench’s shape is mentioned. I’m uncertain whether visitors with no prior knowledge of jewelry making would find this helpful. A short video showing Cooke or another maker in action, or even just a photo of Cooke’s real bench, might have given further context. Nonetheless, this setup is a welcome addition to the exhibition, and the attempt to demystify the fabrication process is noteworthy.

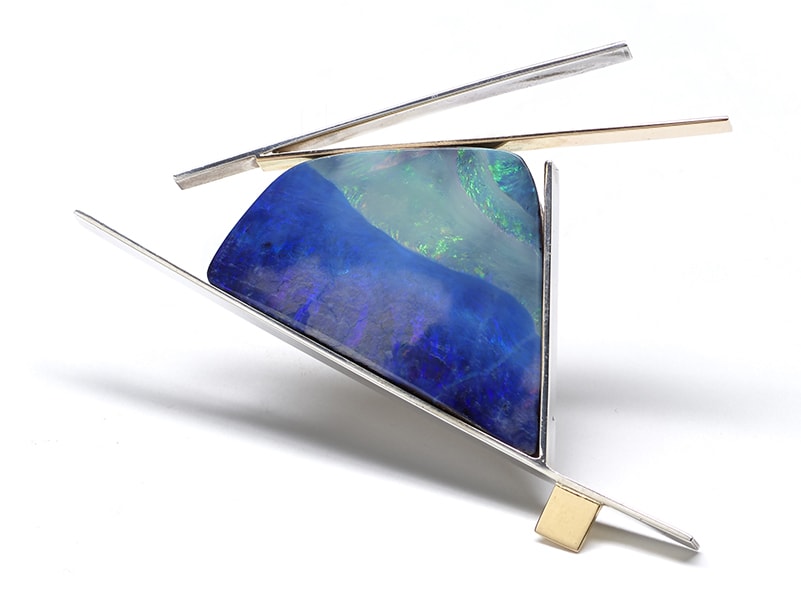

Some of the most striking objects on display were the ones that incorporated color. Color is not found in much of Cooke’s work, so when it’s included it feels like a very specific and deliberate choice. One showcase in particular featured seven pins and rings, all with different sizes and types of stones. What stood out to me is the way that Cooke appeared to have designed her jewelry around the stones in an organic way. Neither the stones nor the metal fabrications demand to be the central focus. Instead, they exist in what I can only describe as a symbiotic relationship in the truest sense.

While Cooke is primarily known for her jewelry, metal isn’t the only medium in which she worked. A series of her sketches and one painting are on display at the beginning of the exhibition. The accompanying wall text explains that Cooke’s father painted landscapes. She began drawing alongside him as a child and continued honing her skills into adulthood. The works shown here date prior to 1957. They’re impressive by themselves, but within the context of this retrospective, they take on new meaning as insightful studies into Cooke’s iterative process. The exhibition notes the similarities of the painting in particular, Water Bird (ca. 1950), to a series of small bird and animal pins that Cooke made between 1950 and 1990, mounted on the opposite wall. The relationship between these objects is incredibly clear. But the depiction of the water as an oblong circle surrounded by an asymmetrical white and yellow border next to the bird is also worth exploring, as it calls to mind so much of the jewelry Cooke would design in the decades to come.

Cooke also designed other types of accessories throughout her career. One of my favorite parts of this exhibition was a small collection of leather handbags she crafted in the 1950s. Even though they differ in size and shape, they are all highly structural and have the same minimalistic, architectural sensibilities as Cooke’s jewelry. They merge form and function in a remarkably timeless way, as if they could be dropped into any period between 1950 to today and fit in effortlessly. Accompanying text informs visitors that these bags are part of a larger, incredibly successful collection that won several design awards. Cooke even published an article in a 1956 issue of Woman’s Day with step-by-step instructions for readers to craft similar bags themselves. A large reproduction of this article appears on the walls surrounding this part of the exhibition.

Commissions are an important part of Cooke’s career. She says she typically enjoys this type of work. She believes her success with it has boiled down to good communication with her clients. A notable example featured within the exhibition is a selection of pieces commissioned by the architect James Rouse for his wife, Patty, to celebrate special occasions such as birthdays and wedding anniversaries. The eight pieces displayed contain many of Cooke’s signature themes. In an added bit of whimsical creativity, numbers are hidden within the designs. These numbers, of course, signify the occasion for which each item was commissioned. The pin pictured here contains the number 65, in honor of Patty’s 65th birthday.

The exhibition concludes with a short off-the-cuff video featuring Cooke along with Fred Lazarus, the former president of MICA, and Ellen Lupton, the current Betty Cooke and William O. Steinmetz Design Chair at MICA. The three discuss some of Cooke’s favorite memories throughout her years. I smiled quite often as she reminisced about things like being mentioned in the local paper because she was caught leaning out the upstairs window of her Tyson Street house in an attempt to paint the exterior. It’s a heartwarming chat that gives visitors a brief sense of who Cooke is as a person, and it serves as the perfect conclusion to this incredible journey through Cooke’s career and legacy.

Editor’s note: The exhibitions was curated by Jeannine Falino, who also wrote the accompanying exhibition catalog.