- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay is an important voice in the postcolonial debate

- Her latest research work is interwoven with her personal history, much of it having to do with jewelry after she discovered that part of her identity had been hidden from her

- The book underscores that identity can be forcibly simplified, officially obliterated. The things that go with that identity can be forgotten, too, when items such as indigenous jewelry are no longer worn

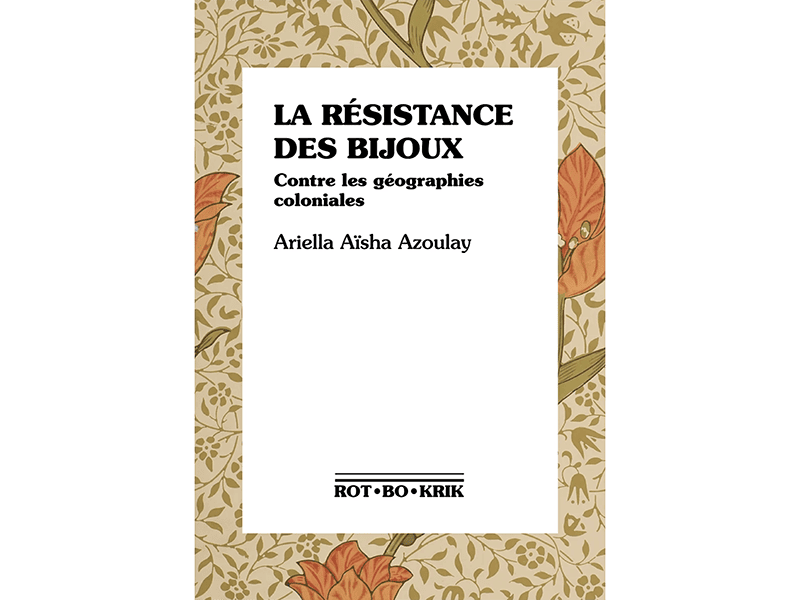

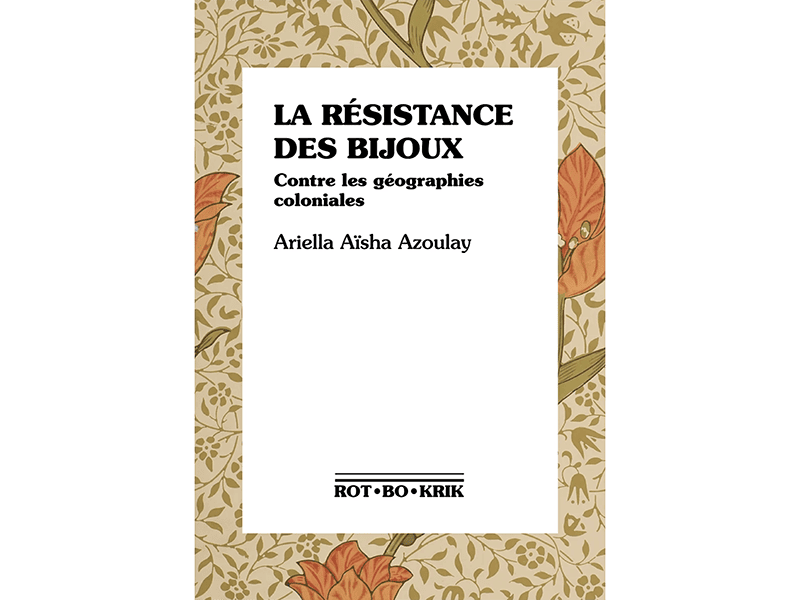

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, La Résistance des Bijoux: Contre les Géographies Coloniales (The Resistance of Jewelry: Against Colonial Geographies). Sète, France: Ròt-Bò-Krik, 2023.

Jewelry can support your identity. This is not breaking news. But how does that work when your identity—Algerian, Jewish, Palestinian—is different from the French, Jewish, Israeli identity you grew up with, as is the case with Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, the author of the book La Résistance des Bijoux: Contre les Géographies Coloniales? How does that work when Arab-Jewish jewelry has been obscured by historic events?

The professor, writer, and filmmaker’s latest research work is interwoven with her personal history. Much of it has to do with jewelry, after Azoulay learned more about her paternal family of “Jewish Muslims” in Algeria. Since before Roman times until 70 years ago, the Jews were present in Arab regions. Their numbers increased after different waves of persecution in medieval Spain and Portugal. By then the Arab world was under Muslim rule, but the Jewish minority was protected. Jews filled occupations such as merchants or craftspeople. As silversmiths they worked in small workshops or traveled from village to village with their tools. Azoulay’s book describes her search for the culture of her ancestors.

Lost Jewish Muslim cultures

The title of this book, which speaks of jewels that can resist, attracted me. But it took me a while to understand this overwhelming and richly illustrated book. Subheadings would have been appreciated. But to be honest, I must blame my poor knowledge of the history of the region.

If Azoulay’s work taught me one thing, it is that identity in North Africa used to be a multilayered thing. One could be Arab or Berber and Muslim or Jewish. Under French rule in countries such as Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, these identities were simplified in the civil registration records. In Algeria, Arab Jews had been registered as French citizens as early as 1870, while the Muslim population had second-class citizenship. This led to friction among these indigenous groups. After independence in the 50s and 60s, the Jews were expelled or sought a better economic future in Europe or the new Israeli State. Azoulay points out that the French imperial system, the promoted Frenchness, and, starting in 1948, the pull of Israel all meant a disruption and eventual erasure of 2,000 years of Jewish presence in North Africa. In her work she presents jewelry as an “invitation to enter the world of destroyed Jewish Muslim cultures.”

An essay, a lament, and many photographs

For a moment it puzzled me that the book cover is a flowery William Morris design. It turns out her small French publishing house uses these designs to honor “an ardent defender of emancipatory art.” La Résistance des Bijoux is not much bigger than a postcard, but still holds 230 pages. It helps to know that the book consists of two reworked ideas articulated earlier.

The first part, translated as The Languages of the Ancestors, is an extended version of an essay first published in the Boston Review. It sketches the moments when the author realized part of her identity had been hidden from her. She grew up in what she now calls the “Zionist colony in Palestine.” She came to see that the Israeli state and Judaism were not a homogeneous people. From her point of view, the state was keen to replace the languages of origin, such as the Arabic and the Judeo-Spanish Ladino in her family, with Hebrew. Many poetic observations color the family’s complicated position. In school, for example, she had to draw a map of Africa, almost indifferent to the fact that she and many of her classmates’ families had just come from North African countries such as Tunisia, which she even accidently forgot to include. Azoulay’s Jewish father came to Israel from Algeria, earning his living as a radio technician and, later, shop owner. He listened to nothing but Radio Monte-Carlo until he died, as if he were a true Gaul. Azoulay’s mother was a third-generation native of Palestine, whose Jewish mother spoke in a heavy Bulgarian accent. In 1948, when Azoulay’s mother was 17 years old, she learned to see Palestine as the enemy. She refused to hear any of her rebellious daughter’s questions.

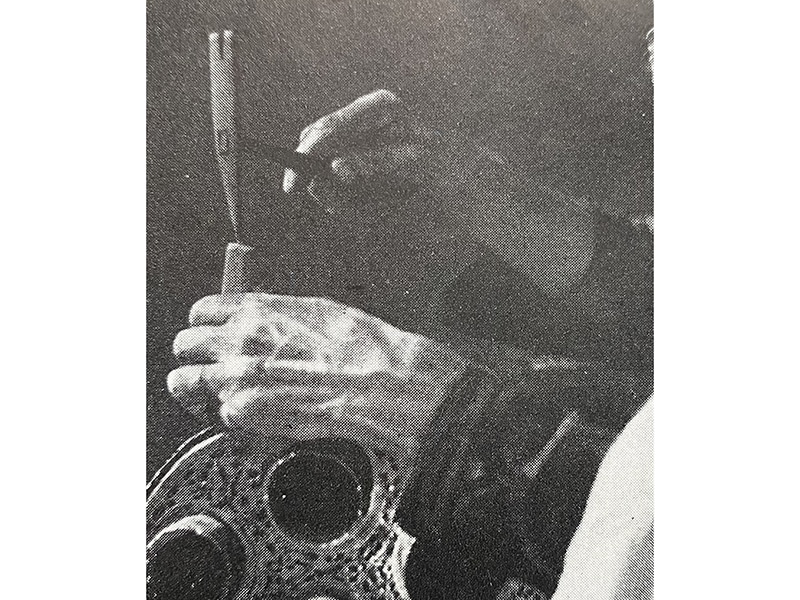

The second part of the book, the title of which translates as The Jews Are Still There, in Every Bracelet, is based on a lecture. She blames the French imperial regime in Algeria for wiping out Jewish communities. She regrets not being able to hold her heritage, the jewelry now in museums in Europe. Here the text is formatted as a poem, its topics viewed from a slightly different angle each time. The musical component of the poem is even clearer in her film essay, The World like a Jewel in the Hand, which addresses the same themes. In it, Azoulay’s documentary voice alternates with a female voice singing the author’s charges.

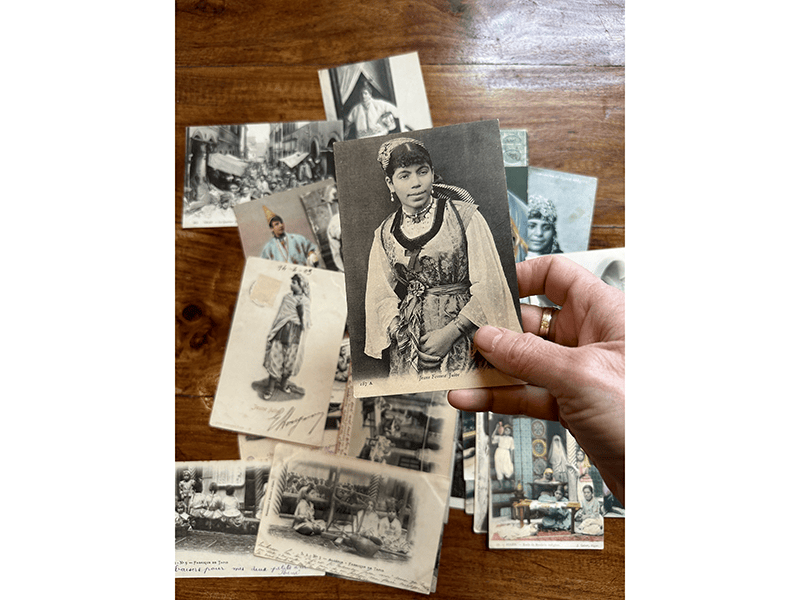

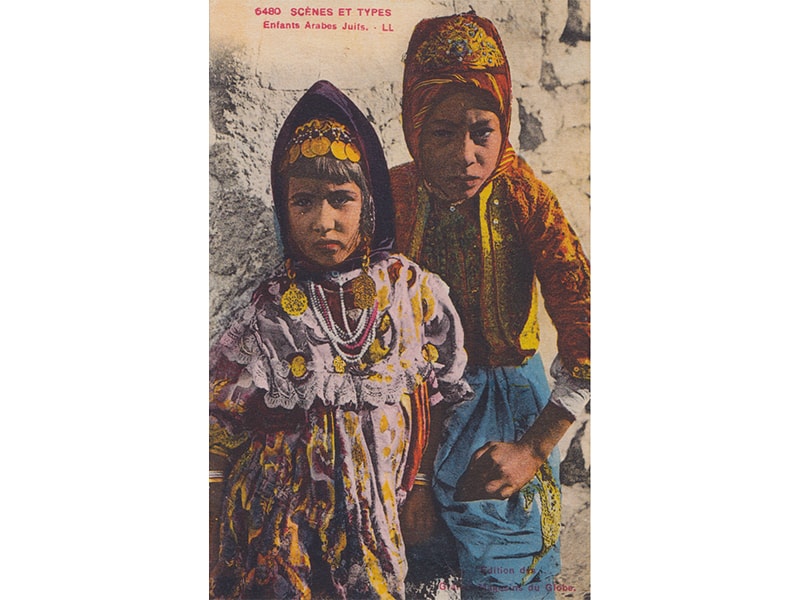

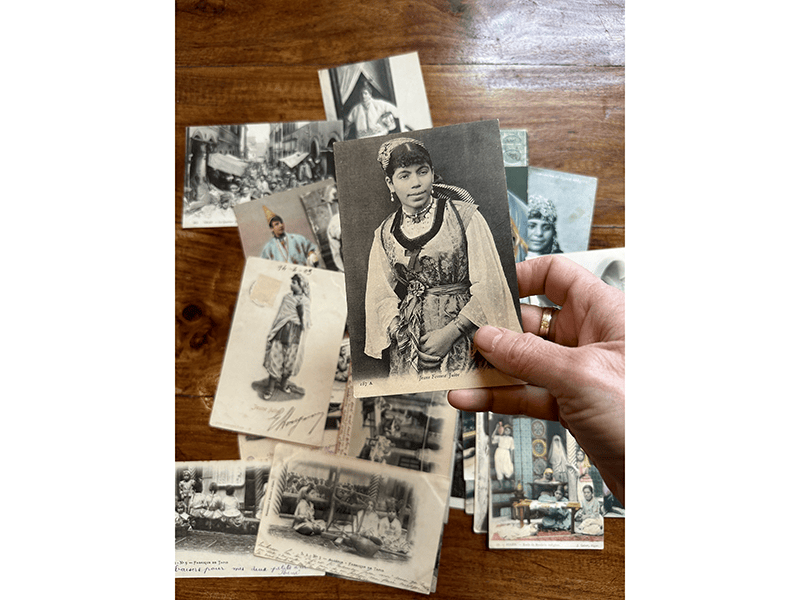

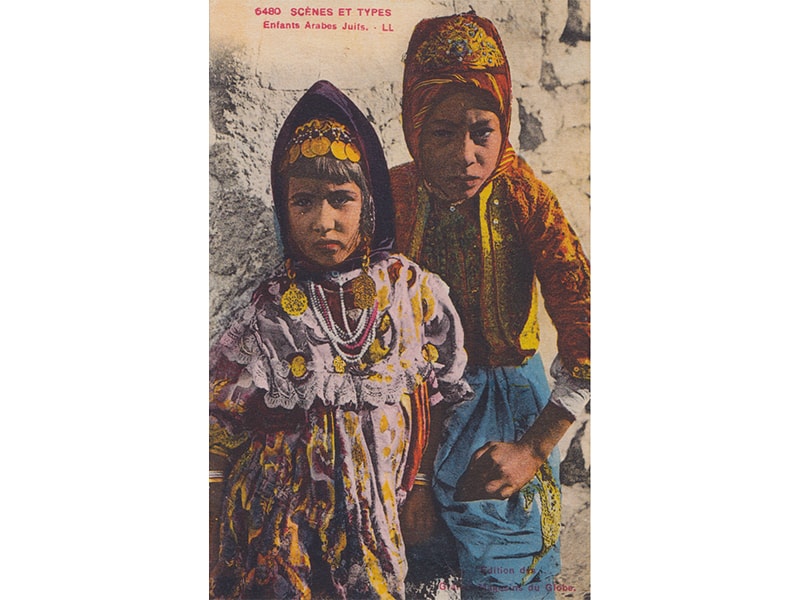

The book contains many full-page images that bring historic Arab jewelry to life. There are images of Jewish jewelry makers and postcards with staged photos of women in local dress. The pages taken from period books on Arab jewelry, written by Europeans, struck me. The art historian in me felt grateful for the documentation. Azoulay, on the other hand, points out that the categorizing itself, often dividing it into either Islamic or Jewish jewelry, is an act of dominance.

A voice on colonial plunder

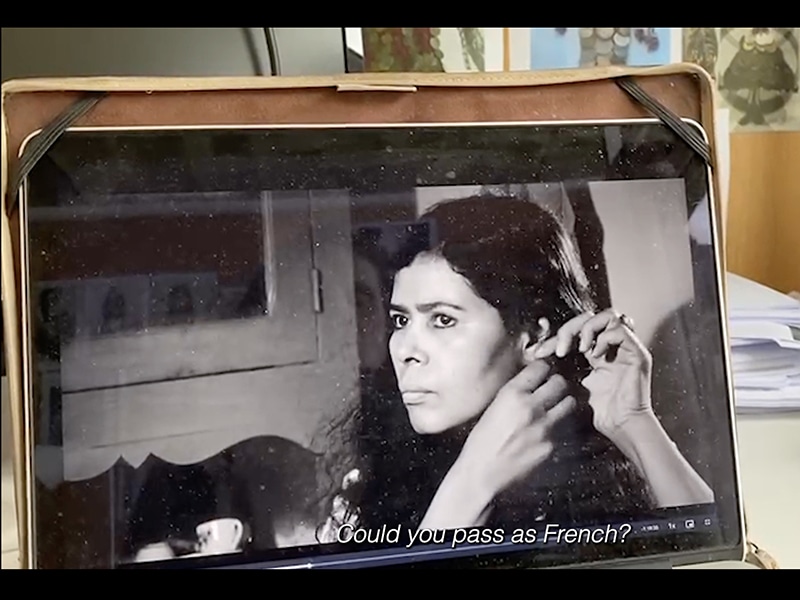

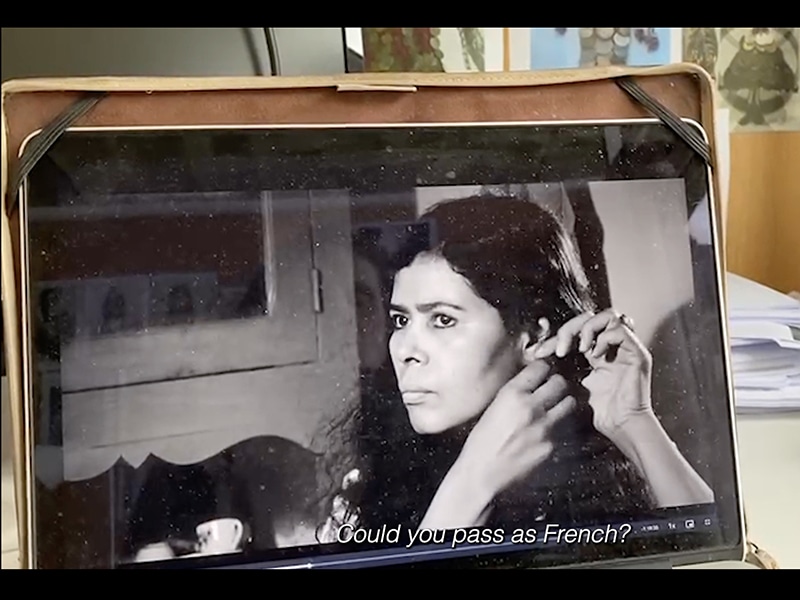

Azoulay is an important voice in the postcolonial debate. She argues that sculptures and jewelry from Africa were seized and placed into European collections. Confined there, they remain unavailable, often misinterpreted, rendered powerless. This, in combination with a higher regard for European-style dress, imposed by the imperial regime, erased Arab cultures. She illustrates this with a scene from the 1966 film The Battle of Algiers. An Algerian mother and her daughters take off their scarves, take the jewelry from their ears and noses, and cut their hair. Their new looks will help them to travel to France. Azoulay is perturbed by how normal it is to see objects separated from their people.

Khamsa

The now “modern”-looking Algerian women in the movie form a sad contrast to life before the French invasion. There are many accounts of people of all backgrounds living as neighbors. Muslims and Jews shared language, beliefs, dishes, and adornment. The khamsa is often mentioned as an example of a symbol beyond religion. This hand-shaped amulet was worn against the evil eye in the entire Arab world. Jewish silversmiths made them for Muslims and Jews alike, in hundreds of varieties.

Azoulay describes her annoyance with encountering contemporary khamsas with a Star of David on them in Morocco. They might be ignorantly meant as a tribute to the Jewish craftspeople who used to make them. But the assignment of the Star of David to Judaism is recent, as is a split into Jewish khamsas and Muslim khamsas. Before, the six-pointed star symbol was owned by all faiths in the region, says Azoulay.

Jewelry that could be Aïsha’s

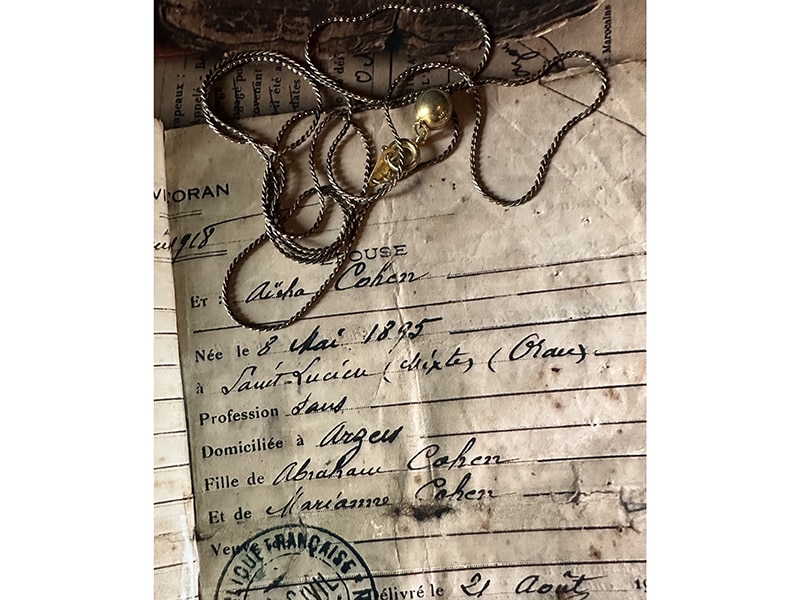

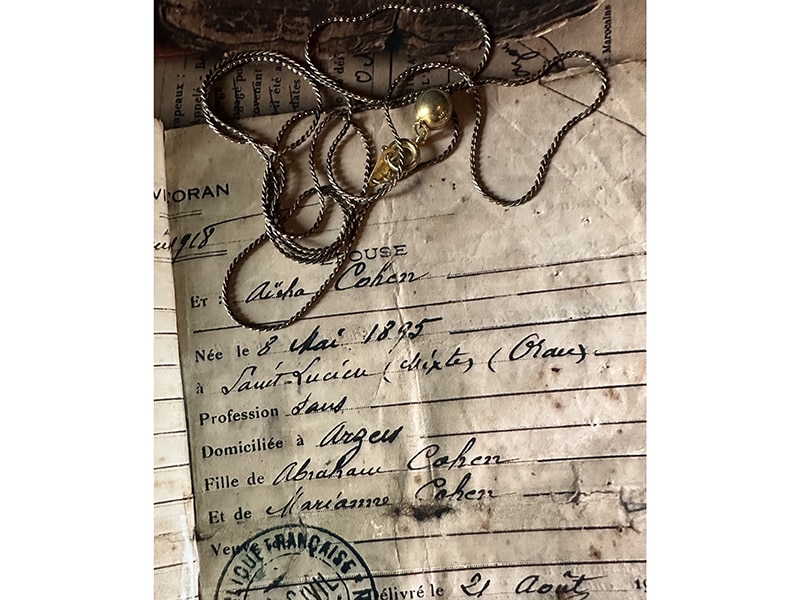

After her father’s death, Azoulay did not find jewelry in his belongings. There were some official documents, however, and on them was written the Muslim first name of her Jewish paternal grandmother, unknown to her until that point: Aïsha. Her grandmother could have been the sister of a woman in one of the postcards, muses Azoulay. She could have been from a family of silversmiths. She could have been wearing a coin pectoral necklace. Raised to be anything but Arab, Ariella Azoulay adopted the name Aïsha, to honor the part of her that is Jewish Algerian Palestinian. And she did something else.

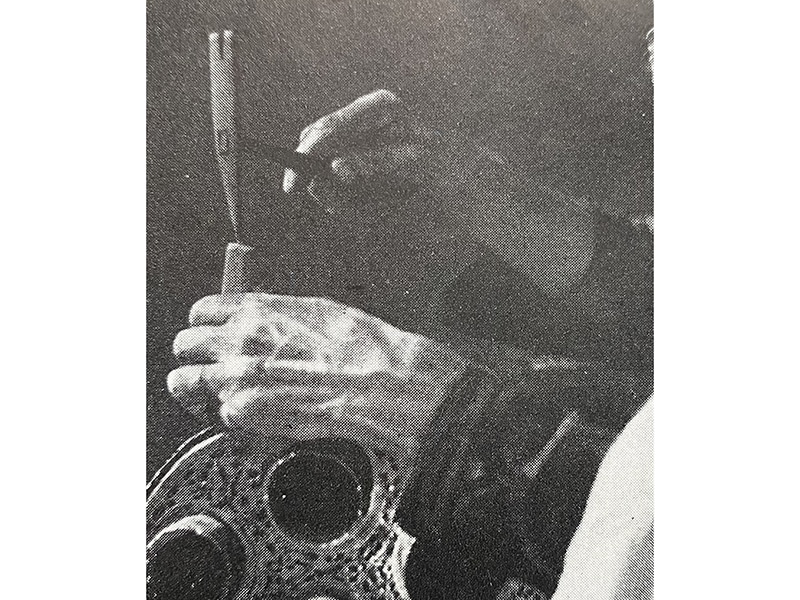

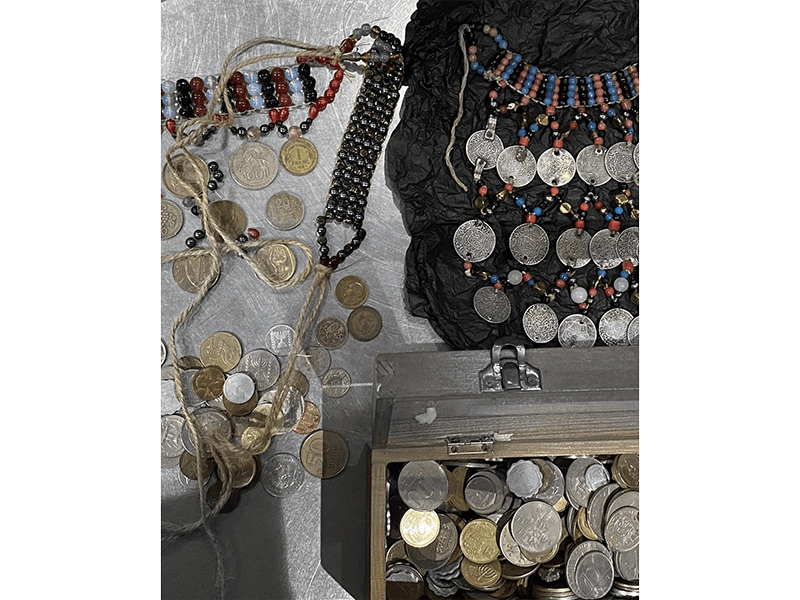

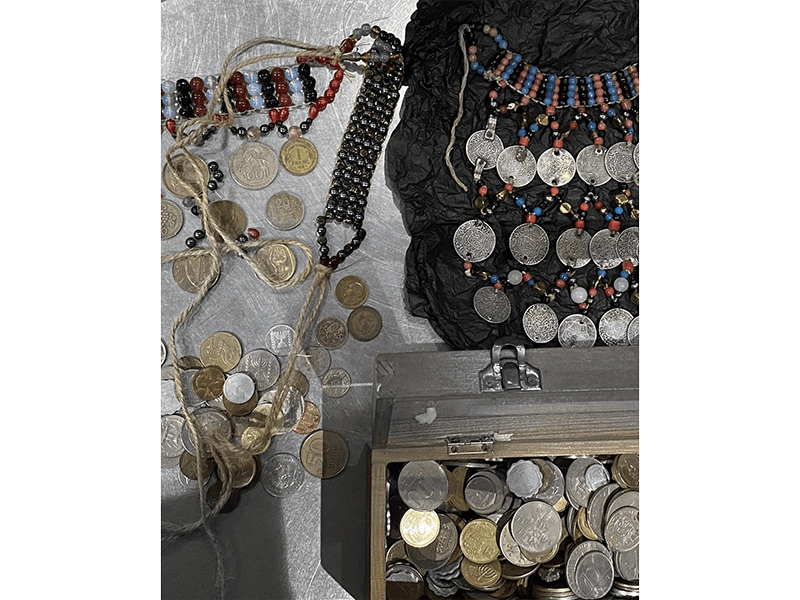

Azoulay’s father’s electronics shop had customers from everywhere. He left a collection of international coins. After drilling holes in them, Azoulay made a couple of coin pectorals similar to pieces from the Mahgreb now in European museums. Not to pretend she had a goldsmith’s skills, but to try to awaken “a muscle memory” she feels she should have from her ancestors who were jewelry makers. It reminded me of jeweler Areta Wilkinson, who painstakingly copied Māori stone tools held in a Cambridge museum. That way, she was able to hold them and feel what her ancestors felt.

Continuity from a world considered lost

La Résistance des Bijoux reminds us that identity can be forcibly simplified, officially obliterated. The things that go with that identity can be forgotten, too, if jewelry is no longer held or worn. In the last 10 years or so, many people have started honoring their denied cultural backgrounds. The insights into Azoulay’s own history could be another of those accounts. The power here is that hers is both touching and linked to a larger social and political picture: I speak of the book’s denseness of information that overwhelmed me at first.

Azoulay’s book, and let’s not forget her film, try to show that there is still a continuity from that world considered “disappeared.” The act of reconstituting Jewish Muslim jewelry that she describes as held captive in museum glass cases is an interesting attempt to make this point tangible.

Sources

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Algeria: The Jews Are Still There, in Every Bracelet. Lisa and Heinrich Arnhold Lecture 2022, the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden in cooperation with The American Academy in Berlin, Dresden, April 27, 2022.

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. “Unlearning Our Settler Colonial Tongues:

On Language and Belonging.” Boston Review (November 30, 2021). https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/unlearning-our-settler-colonial-tongues/

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, dir. The World like a Jewel in the Hand. Un-learning Imperial Plunder II. 2022. Documentary shot during the exhibition Errata (Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona, co-curated with Carles Guerra). Screenings are announced on the events page of Azoulay’s publisher, https://www.rot-bo-krik.com/evenements.

Gross, William, Gabriele Holthuis, and Shimon Stein. Living Khamsa. Die Hand zum Glück. The Hand to Fortune. Schwäbisch Gmünd: Museum und Galerie im Prediger, 2004. Exhibition catalog.

We welcome your comments on our publishing and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

Les Bijoux qui Résistent

Une Revue de La Résistance des Bijoux: Contre les Géographies Coloniales

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, La Résistance des Bijoux: Contre les Géographies Coloniales. Sète, France: Ròt-Bò-Krik, 2023.

Les bijoux peuvent soutenir votre identité. Ce n’est pas une nouvelle d’actualité. Mais comment cela fonctionne-t-il lorsque votre identité—algérienne, juive, palestinienne—est différente de l’identité française, juive, israélienne avec laquelle vous avez grandi, comme c’est le cas d’Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, l’auteur du livre La Résistance des Bijoux: Contre les Géographies Coloniales? Comment cela fonctionne-t-il alors que les bijoux arabo-juifs ont été obscurcis par des événements historiques?

Le dernier travail de recherche de la professeure, écrivaine et cinéaste sont étroitement liés à son histoire personnelle. Cela concerne en grande partie les bijoux, après qu’Azoulay en ait appris davantage sur sa famille paternelle de « juifs musulmans » en Algérie. Avant l’époque romaine et jusqu’il y a 70 ans, les Juifs étaient présents dans les régions arabes. Leur nombre a augmenté après différentes vagues de persécutions dans l’Espagne et le Portugal médiévaux. Le monde arabe était alors sous domination musulmane, mais la minorité juive était protégée. Les Juifs exerçaient des professions telles que marchands ou artisans. En tant qu’orfèvres, ils travaillaient dans de petits ateliers ou se déplaçaient de village en village avec leurs outils. Le livre d’Azoulay décrit sa recherche de la culture de ses ancêtres.

Cultures juives musulmanes perdues

Le titre de ce livre, qui parle de bijoux qui peuvent résister, m’a séduit. Mais il m’a fallu du temps pour comprendre ce livre bouleversant et richement illustré. Des sous-titres auraient été appréciés. Mais pour être honnête, je dois blâmer ma mauvaise connaissance de l’histoire de la région.

Si le travail d’Azoulay m’a appris une chose, c’est que l’identité en Afrique du Nord était autrefois une chose à plusieurs niveaux. On pouvait être arabe ou berbère, et musulman ou juif. Sous la domination française, dans des pays comme le Maroc, l’Algérie, et la Tunisie, ces identités étaient simplifiées dans les actes d’état civil. En Algérie, les Juifs arabes étaient enregistrés comme citoyens français dès 1870, tandis que la population musulmane avait une citoyenneté de seconde zone. Cela a conduit à des frictions entre ces groupes indigènes. Après l’indépendance dans les années 50 et 60, les Juifs ont été expulsés ou ont cherché un avenir économique meilleur en Europe ou dans le nouvel État israélien. Azoulay souligne que le système impérial français, la promotion de la francité et, à partir de 1948, l’attraction d’Israël ont tous signifié une perturbation et finalement l’effacement de 2 000 ans de présence juive en Afrique du Nord. Dans son travail, elle présente les bijoux comme une « invitation à entrer dans le monde des cultures juives musulmanes détruites ».

Un essai, une complainte, et de nombreuses photos

Pendant un moment, j’ai été perplexe par le fait que la couverture du livre soit un dessin fleuri de William Morris. Il s’avère que sa petite maison d’édition française utilise ces dessins pour honorer « un ardent défenseur d’un art émancipateur ». La Résistance des Bijoux est à peine plus grand qu’une carte postale, mais contient tout de même 230 pages. Il est utile de savoir que le livre se compose de deux idées retravaillées et articulées plus tôt.

La première partie, Les Langues des Ancêtres, est une version étendue d’un essai publié pour la première fois dans la Boston Review. Il décrit les moments où l’auteur a réalisé qu’une partie de son identité lui avait été cachée. Elle a grandi dans ce qu’elle appelle aujourd’hui la « colonie sioniste en Palestine ». Elle en est venue à comprendre que l’État israélien et le judaïsme ne formaient pas un peuple homogène. De son point de vue, l’État souhaitait remplacer les langues d’origine, comme l’arabe et le ladino judéo-espagnol de sa famille, par l’hébreu. De nombreuses observations poétiques colorent la situation compliquée de la famille. À l’école, par exemple, elle devait dessiner une carte de l’Afrique, presque indifférente au fait qu’elle et beaucoup de familles de ses camarades de classe venaient tout juste de pays d’Afrique du Nord comme la Tunisie, qu’elle avait même accidentellement oublié d’inclure. Le père juif d’Azoulay est arrivé d’Algérie en Israël, gagnant sa vie comme technicien radio et, par après, propriétaire de magasin. Il n’a écouté que Radio Monte-Carlo jusqu’à sa mort, comme s’il était un vrai Gaulois. La mère d’Azoulay était originaire de Palestine de troisième génération, dont la mère juive parlait avec un fort accent bulgare. En 1948, alors que la mère d’Azoulay avait 17 ans, elle apprit à considérer la Palestine comme un ennemi. Elle a refusé d’entendre les questions de sa fille rebelle.

La deuxième partie du livre, avec le titre Les Juifs Sont Encore Là, dans Chaque Bracelet, est basée sur une conférence. Elle accuse le régime impérial français d’Algérie d’avoir anéanti les communautés juives. Elle regrette de ne pas pouvoir tenir son patrimoine, les bijoux désormais présents dans les musées d’Europe. Ici, le texte est formaté comme un poème, ses sujets étant à chaque fois abordés sous un angle légèrement différent. La composante musicale du poème est encore plus claire dans son essai cinématographique, dont le titre se traduit Le Monde Comme un Joyau dans la Main, qui parle des mêmes thèmes. La voix documentaire d’Azoulay y alterne avec une voix féminine chantant les accusations de l’auteur.

Le livre contient de nombreuses images pleine page qui donnent vie aux bijoux arabes historiques. Il y a des images de créateurs de bijoux juifs et des cartes postales avec des photos mises en scène de femmes en costume local. Les pages tirées d’ouvrages d’époque sur les bijoux arabes, écrits par des Européens, m’ont frappé. L’historien de l’art en moi était reconnaissante pour la documentation. Azoulay, en revanche, souligne que la catégorisation elle-même, en la divisant souvent entre bijoux islamiques ou juifs, est un acte de domination.

Une voix sur le pillage colonial

Azoulay est une voix importante dans le débat postcolonial. Elle affirme que sculptures et bijoux d’Afrique ont été saisis et placés dans des collections européennes. Confinés là, ils restent indisponibles, souvent mal interprétés, rendus impuissants. Ceci, combiné à une plus grande estime pour les vêtements de style européen, imposés par le régime impérial, a effacé les cultures arabes. Elle illustre cela avec une scène du film de 1966 The Battle of Algiers (La Bataille d’Alger). Une mère algérienne et ses filles enlèvent leurs foulards, retirent les bijoux de leurs oreilles et de leur nez et se coupent les cheveux. Leurs nouveaux looks les aideront à voyager en France. Azoulay est perturbée par la normalité de voir des objets séparés de leur peuple.

Khamsa

Les femmes algériennes désormais « modernes » du film contrastent tristement avec la vie d’avant l’invasion française. Il existe de nombreux récits de personnes de tous horizons vivant en voisins. Les musulmans et les juifs partageaient la langue, les croyances, les plats et les ornements. La khamsa est souvent citée comme exemple de symbole au-delà de la religion. Cette amulette en forme de main était portée contre le mauvais œil dans tout le monde arabe. Les orfèvres juifs les fabriquaient aussi bien pour les musulmans que pour les juifs, dans des centaines de variétés.

Azoulay décrit son mécontentement à l’idée de rencontrer des khamsas contemporains portant une étoile de David au Maroc. Ils pourraient être, par ignorance, considérés comme un hommage aux artisans juifs qui les fabriquaient. Mais l’attribution de l’étoile de David au judaïsme est récente, tout comme la scission entre les khamsas juifs et les khamsas musulmans. Avant, l’étoile à six branches appartenait à toutes les confessions de la région, explique Azoulay.

Des bijoux qui pourraient être ceux d’Aïsha

Après la mort de son père, Azoulay n’a pas trouvé de bijoux dans ses affaires. Il existait par contre quelques documents officiels sur lesquels était inscrit le prénom musulman de sa grand-mère paternelle juive, qui lui etait inconnu jusque-là: Aïsha. Sa grand-mère aurait pu être la sœur d’une femme figurant sur l’une des cartes postales, songe Azoulay. Elle pourrait être issue d’une famille d’orfèvres. Elle aurait pu porter un collier pectoral en forme de pièce de monnaie. Élevée pour être tout sauf arabe, Ariella Azoulay a adopté le nom d’Aïsha, pour honorer la partie d’elle qui est juive algérienne palestinienne. Et elle a fait autre chose.

Le magasin d’électronique du père d’Azoulay avait des clients de partout. Il a laissé une collection de pièces de monnaie internationales. Après y avoir percé des trous, Azoulay réalisa quelques pièces pectorales semblables à des pièces du Mahgreb aujourd’hui conservées dans les musées européens. Non pas pour prétendre qu’elle possédait des compétences d’orfèvrerie, mais pour tenter de réveiller « une mémoire musculaire » qu’elle estime devoir tenir de ses ancêtres joailliers. Cela m’a rappelé la joaillière Areta Wilkinson, qui copiait minutieusement les outils en pierre maoris conservés dans un musée de Cambridge. De cette façon, elle pouvait les tenir et ressentir ce que ressentaient ses ancêtres.

Continuité d’un monde considéré perdu

La Résistance des Bijoux nous rappelle que l’identité peut être simplifiée par la force, officiellement oblitérée. Les éléments qui correspondent à cette identité peuvent également être oubliés si les bijoux ne sont plus détenus ou portés. Au cours des dix dernières années, de nombreuses personnes ont commencé à honorer leurs origines culturelles niées. Les aperçus sur la propre histoire d’Azoulay pourraient être un autre de ces récits. Le pouvoir ici est que le sien est à la fois touchant et lié à un tableau social et politique plus large: je parle de la densité d’informations du livre qui m’a d’abord submergé.

Le livre d’Azoulay, et n’oublions pas son film, tentent de montrer qu’il existe encore une continuité avec ce monde considéré comme « disparu ». L’acte de reconstituer des bijoux juifs musulmans qu’elle décrit comme retenus captifs dans des vitrines de musée est une tentative intéressante pour rendre ce point tangible.

Une liste de références est donnée sous la rubrique « Sources », à la fin du texte anglais.

Nous apprécions vos commentaires sur notre publication et publierons vos lettres qui abordent nos articles de manière réfléchie et polie. Veuillez soumettre toutes lettres à l’éditeur par voie électronique ; faites-le ici.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org