Also Known As Jewellery* is a hybrid model, somewhere between a survey exhibition – seventeen of the best French or French-based jewelers who are contributing to the ‘spectacular evolution’ of contemporary jewelry in France – and an argument about what contemporary jewelry is and does. According to the curators/editors, the title ‘underlines the specificity of contemporary jewellery and the ambiguity inherent to a craft-based, boundary-pushing practice,’ resulting in an exhibition of jewellery that is ‘both alien to its tradition and well versed in its history.’ The project dodges the responsibility of representing French jewelry in favour of ‘younger jewellers’ who ‘are making their mark by adopting a critical stance towards the medium itself and fuelling their research with conceptual nuggets originated mostly outside the field of craft. They invite us, in turn, to look at other disciplines (sociology, anthropology, literature, philosophy, as well as architecture, cinema, and photography) to question the accepted definition of jewellery.’

This is not bad as introductions go, but I would have liked to have a bit more in the way of history, context and argument. A text that fits comfortably on the front cover of the smaller than A-4 sized catalog is not necessarily enough of an introduction to a practice that, as the curators/editors write themselves, is a ‘rather under-exposed part of the European contemporary jewellery community.’ We are told briefly about the challenge of France’s strong history in luxury goods and precious materials. A rebel group called EPOC that formed in the 1970s is name-checked but left unexplained. To know the context of this work, to understand why France is an outsider in the European jewelry community, to learn more about how French jewelry relates (however briefly) to a story of twentieth century contemporary jewelry, would be an excellent addition to this publication.

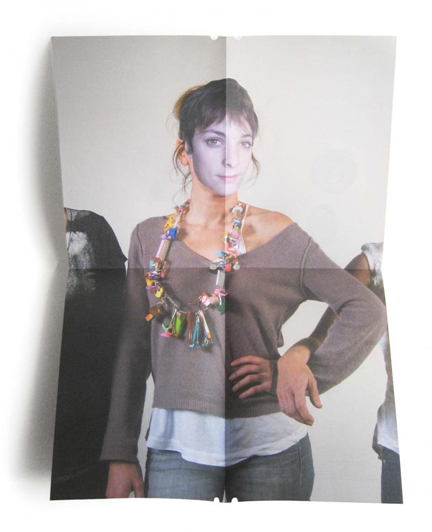

The curatorial/editorial statement on the front cover is joined by contents information on the back cover (jewelers, writers, photographers, etc.) and acknowledgments and various gallery and institutional statements on the inside flaps. All the texts are in French and English, which sends a nice message that this is a publication for a local as well as an international audience. The catalog itself is held together by a rubber band along the spine. When you remove it, the pages with text and images related to each jeweler unfold to reveal a photographic frieze of the jewelers (or their dopplegangers, stand-ins wearing masks) on the other side. I’m not sure what the purpose of this particular design strategy is and I don’t know how many readers will access it, or care. (The photographs reveal the jewels being worn, in action so to speak, but this isn’t enough of a reward to invest the effort involved in dismantling – and more importantly, reassembling – the pages.)

The catalog essays are all about 500 words long and it is quite remarkable what these authors manage to pack into that relatively short space. And as you read through them, the value of choosing writers from various disciplines to analyse the work becomes apparent. Mostly the pairings of jewelers and authors are skilfully done. Sociologist Sofian Beldjerd discusses Claire Bologe’s necklaces in terms of sociological models of the individual, revealing a theorization not only of the form of this jewelry but of its relation to the self. ‘The necklaces engage their wearer in a reflexive mise-en-abîme of the means of taking possession of oneself,’ writes Beldjerd, in an account that is perfectly pitched to the particular nuances of the objects as jewelry. Socio-anthropologist Philippe Liotard writes about Emmanual Lacoste’s golden tongue and silicon entrails as a reversal of usual ‘staging of anatomy that is reassuring in its medical, rational side.’ ‘The intimacy of flesh is less reassuring when it is exposed by an artistic act,’ writes Liotard, who argues that Lacoste makes jewelry (traditionally a practice of permanence) dedicated to the finite and mortal. Poet and translator Jacques Demarcq creates a fairytale-cum-faux anthropology to explain Amandine Meunier’s cut inner-tube necklaces, which sidles up to the objects in an unexpected and quite refreshing manner.

And then there are the well-written, well-argued texts, not necessarily special because of some kind of nifty conceptualised fit between maker and author, but because of the good old-fashioned sharp analysis. This is true of pretty much all the texts, meaning that by the time you have finished reading the catalog you are well-informed about these seventeen practices and the kind of contributions that French jewelers are making to contemporary jewelry discussions.

All of which is really to say that I was disappointed not to find anything about the way French jewelry enriches or challenges our existing notion of contemporary jewelry. It would be nice to think that something strange, even a little nasty, has been brewing away in the French darkness, behind a curtain of invisibility. (A jewelry equivalent to those stinky, unpasteurised cheeses that thrill and horrify the rest of the world.) Without a few more pointers from the curators/editors, it is impossible to know if this might be true and we are left with the assumption that probably it is business as usual, with French jewelry contributing another quantity of high-quality contemporary jewelry that follows the recipe cooked up in the European centres (Amsterdam, Munich) and exported all around the world.

Then again, this might be too much expectation to place upon this particular project. Having brought contemporary jewelry in France to our attention and provided us with an introduction to what we are seeing, the work of integrating these jewelers and their practices into the wider story of contemporary jewelry can now begin.