February 21—December 23, 2020

Thomas E. Cabaniss Historic Residence, Gregg Museum of Art & Design, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina, US

All Is Possible is the first museum retrospective of the work of American metalsmith, educator, and industrial designer Mary Ann Scherr (1921–2016). This is surprising, considering the length and breadth of her career, her many innovations, and her influence on the field of metalsmithing. The title, a slogan that appears on two of Scherr’s bracelets in the exhibition, alludes to her life story; according to curator Ana Estrades, it conveys Scherr’s “zest for life and dedicated mentorship … the many creative possibilities she saw in metal design…the challenges of a woman working in her time.”[1]

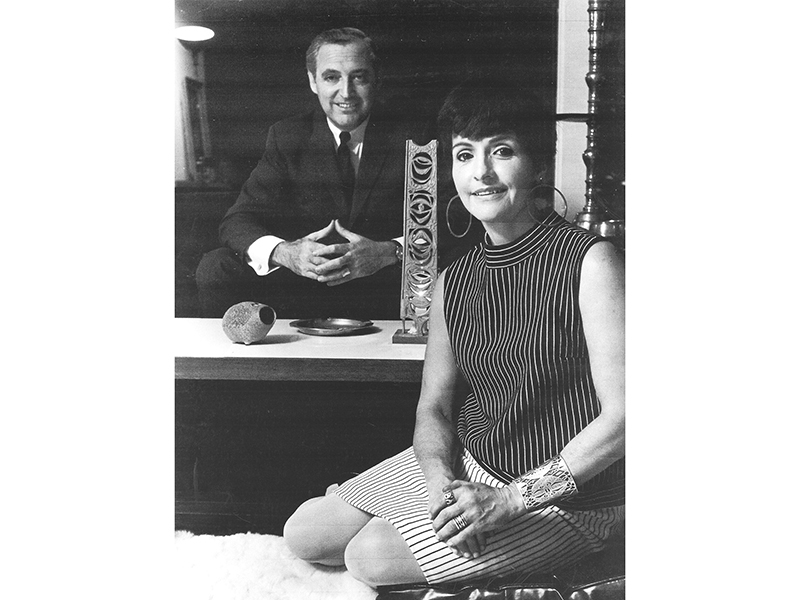

From the 1940s to the 1980s, Scherr and her husband and fellow designer Sam Scherr ran a design firm for which Scherr designed (and sometimes fabricated) clothing, appliances, graphics, murals, and a range of other products for companies large and small.

In 1950, amid her design career and while home with a new baby, she took a night class on metalsmithing at the Akron Art Institute in her home city of Akron, Ohio, US, and was hooked. Within two years, Scherr was teaching all the metals classes at the Institute and went on to teach the subject at Kent State University from 1960 until 1976, when Sam was tapped to head the American Craft Council and the couple moved to New York City. There, she taught jewelry at the Parsons School of Design and chaired its department of product design for six years. All the while, Scherr was working and exhibiting as a metalsmith and jeweler, innovating several techniques for metal surface treatments along the way that she shared through her teaching, publications, and exhibitions. She also taught metals workshops throughout the United States and abroad, some sponsored by USAID. In 1989, the Scherrs moved to Raleigh, NC, where their three adult children lived. Mary Ann continued working as an artist and teaching at local colleges, universities, and the Penland School of Crafts, where she taught every summer from 1968 to 2018.

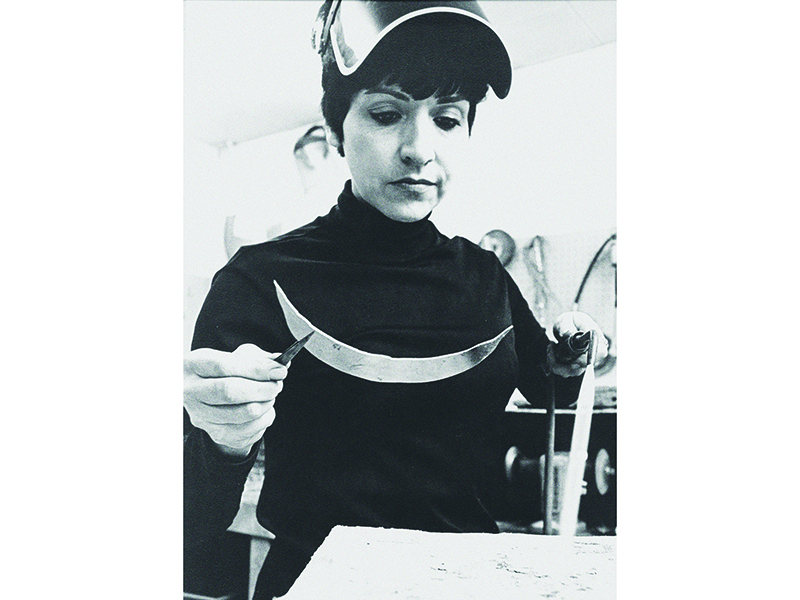

Scherr is perhaps best known for her body monitor jewelry—decades before the Fitbit or Apple Watch, she envisioned wearable devices that would monitor vital signs or air quality using electronics and liquid crystal displays, housed in ornamented metal pendants, bracelets, and other forms of adornment. She conceived the first body monitor in 1969, developed other ideas into prototypes in the 1970s, and continued working on them intermittently into the 2010s. To create functional devices, Scherr collaborated with biomedical researchers, electronics engineers, and other experts; hers was a STEAM-focused[2] project before that acronym was coined. Although none went into production due to the challenges of technology and regulation, they were widely published and praised, and remain relevant to our current era of personal electronics. I first learned of both Scherr and the body monitors in 2010 from the textbook Makers: A History of American Studio Craft[3] and have been wanting to see some in person since then. That opportunity alone made reviewing All Is Possible worthwhile for me, but I was equally pleased to see a broad range of her work.

The presence of Scherr’s retrospective at the Gregg Museum and the contents of the exhibition reflect her longstanding involvement in the arts community in Raleigh and around North Carolina. In addition to teaching at Meredith College, Duke University, and the College of Design and the Crafts Center at NC State, and in her home studio, she cofounded a local artists’ cooperative gallery and served with arts organizations, including on the board of the Friends of the Art Gallery at NC State, later renamed the Gregg Museum, on whose board she also served. Scherr’s retrospective likely would have happened at the Gregg while she was alive except that she and the museum’s director and curator, Roger Manley, agreed it should happen after she rotated off the board. They discussed the project in 2014, but then Scherr became involved with other projects and unfortunately passed away in 2016 before they could pursue the exhibition further.[4] It remained a high priority for Manley as the museum opened its new facility in 2017; then the following year, art historian and independent curator Ana Estrades contacted him to say she was moving to the area and asked if the museum had any projects she might work on. Originally from Spain, Estrades had recently earned an MA from the Bard Graduate Center with a focus on jewelry history. With a background in museum education, teaching, writing, and curating, Estrades seemed the ideal curator for the Scherr retrospective.[5]

Estrades was not familiar with Scherr or her work when she began the project, but as Manley notes in the catalog, that enabled her to “bring fresh eyes and a passionate curiosity to the task.”[6] Her label and catalog text, article on Scherr for Metalsmith magazine, and recorded virtual talk reflect thorough research, not only through published and archival sources but by interviewing Scherr’s two sons who live in the Raleigh area; her daughter, who lives in Santa Fe; and many of her former students and studio assistants in the area.[7] Most of these individuals also lent work to the exhibition. Nearly all of the 140 works included came from the Gregg Museum’s collection, the Scherr family (who gave Estrades access to their archive that included prototypes and an unpublished autobiography), and the other local lenders. Estrades found that these resources covered the breadth of the artist’s work so well that only one institutional loan was needed—the Heart Pulse Sensor bracelet from the Museum of Arts and Design, New York.

All Is Possible surveys Scherr’s full career, beginning with her design work in the 1940s and 1950s, but concentrates on her jewelry and on the latter half of her career, from the 1980s to the 2010s. This choice by Estrades resulted in a cohesive and elegant presentation that makes smart use of the relatively small exhibition space. The exhibition was installed in the Thomas E. Cabaniss Historic Residence, the 1927 Georgian home that housed the chancellor until 2011, where the former dining room, entry hallway, and living room are now outfitted as gallery spaces comprising around 1,000 square feet altogether. Estrades divided Scherr’s design and jewelry work chronologically and thematically among the three rooms. From the Gregg Museum’s entrance in its newer purpose-built wing, visitors entered the former dining room of the historic residence, where they were introduced to Scherr through biographical wall labels and early work. This included framed renderings of 1940s automobiles and 1950s maternity dresses; floor cases of product designs from the 1950s to the 1970s; and a wall case of eight body monitors and related jewelry and drawings dating from 1969 to the 1990s.

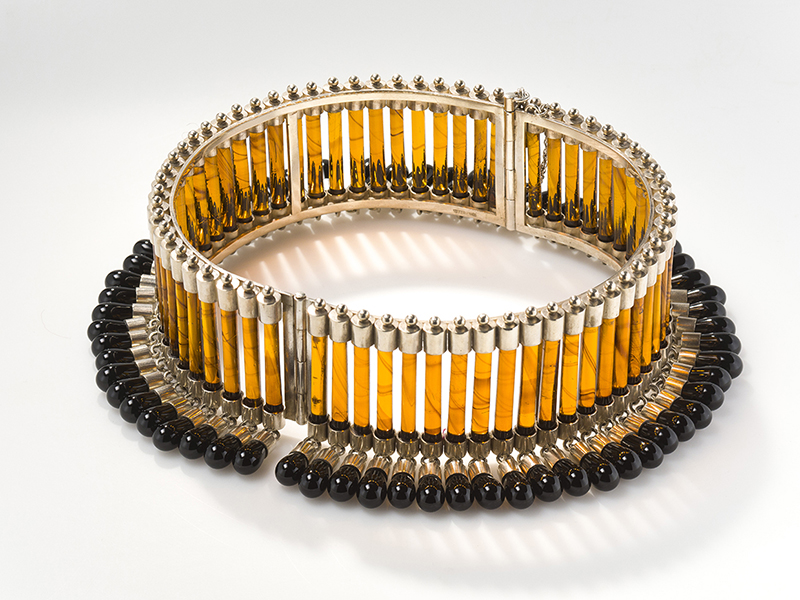

In the adjacent two rooms, Estrades grouped Scherr’s jewelry, mostly dating from the 1970s to the 2010s, in wall cases according to themes and typologies. In the entry hall are Scherr’s major commissions, jewelry sets, and work in anodized titanium, while the final room includes cases that group together earrings, cuff bracelets, necklaces, and rings (and a few brooches). Organizing the exhibition this way, Estrades argues, allows viewers to appreciate the fertility of Scherr’s creative mind—the multitude of ways she approached each form. Like other modernists of her era, she drew inspiration from many cultures and styles, past and present, including ancient Egypt and Rome, West African art, Art Nouveau and Art Deco, minimalism, biomorphism, and more. She continuously explored new techniques for shaping, coloring, texturing, and otherwise decorating various metals, and although her interests shifted among them, Scherr did not work in distinct phases that would lend themselves to a chronological retrospective.

The Cabaniss Residence offered an intriguing setting for the exhibition. It retains references to its previous domestic use, with items such as chandeliers, fireplaces, and a grand piano in the former living room (which the museum presumably has used for concerts), but with the addition of off-white walls, track lights, and no other furnishings it is a semi-neutral gallery space. Scherr’s jewelry, drawings, small metal sculptures, and product designs—which included a ceramic cookie jar, a rubber bouncing toy, and a countertop oven/broiler—felt at home in the modestly scaled rooms of a house that was built and lived in during the time when the works were created, even though the house had no historical connection with the objects.

The space offers both advantages and limitations for any exhibition installed in it. In this era in which exhibitions are expected to be Instagrammable experiences, many of the design elements that museums use to grab visitors’ attention, such as focused lighting, wall paint, vinyl graphics, and photomurals, cannot be used in the Cabaniss Residence, either because they would harm the space or because they don’t work aesthetically. For All Is Possible, this necessitated a minimalist installation of plain, straightforward text panels and cases in which the jewelry either rested on shelves or had inconspicuous mounts. Scherr’s jewelry and objects were the focus of attention and the exhibition avoided the potential problem of overpowering such small works of art. Yet, in some ways the subtle installation downplayed the importance of this, the first comprehensive look at Scherr’s oeuvre.

While flashy colors and graphics certainly were not necessary, I would have liked to see Scherr’s flair for pattern picked up in the graphic design of the text panels. This would have created a visual through-line among the three rooms and branded the exhibition with a bit of her personality. However, I can well imagine that the budget may have precluded this.

Instead, the Gregg allocated resources to elements that contribute to the exhibition’s success by expanding its reach and duration beyond the space and time of the physical installation. These include an introductory video, the aforementioned recorded talk by Estrades, the exhibition catalog, and a virtual tour.[8] All Is Possible opened on February 20, 2020, and the Gregg Museum closed due to the pandemic just weeks later, only reopening again by appointment in the fall, making the catalog and online aspects even more valuable. The popularity of digital offerings across the arts sector during quarantine suggests that audiences will continue to want them even without a pandemic. Virtual tours are an important addition to these offerings because unlike most catalogs, they show viewers how the combination of objects and installation design created meaning. Whereas in the past the public might only see a few published installation photographs, now virtual tours allow more exhibitions to be part of the global discourse around how objects are displayed.

Ironically, despite disrupting the exhibition’s run, the pandemic only underlined the relevance of Scherr’s work, particularly the body monitors. Her foresight was already apparent to those who knew her work when Fitbits became popular, but in 2020 people became even more attuned to their bodies and interested in monitoring their vital signs as we all looked for any possible symptoms of COVID-19 and had our temperatures checked before entering workplaces and stores. As a studio jeweler, Scherr could not take on the demanding task of navigating government regulations and bringing her body monitors to market (although she did secure several patents). It is unfortunate that no other entrepreneurs took up the challenge so consumers could benefit from the combination of function and aesthetics that Scherr’s inventions offered. (I wish Scherr’s Oxygen Supply Pendant had existed when I was a teenager with asthma in the 1990s.)

Many of the body monitors feature sterling silver etched with intricate patterns, another area of technical innovation for Scherr and one of several that All Is Possible highlighted. The many examples of etched work on view showed how she continued to explore the process across her career. In the 1990s, she invented instant etching, a safer and quicker method that used a new type of printer to transfer a photograph or design to metal. She also often etched both sides of a piece of metal to replace sawing and piercing. Scherr even etched stainless steel, a metal she began experimenting with in 1961 when the company U.S. Steel commissioned her to make a collection of jewelry from it. Other innovations emerged from that project, with Scherr using various oils and heat to patinate steel in several colors (making “stainless” a misnomer) and mastering a new set of workshop tools for this obstinate metal. In a similar way, Scherr embraced titanium, a metal that became prominent in postwar science and technology, anodizing it to create a multitude of colors (as seen in the Grapes Necklace) and using resists to create motifs such as the crisp geometric patterns on a cuff bracelet.

Scherr originally studied graphic design and illustration at the Cleveland Institute of Art, then began a career in design that later overlapped with her work in jewelry. Her varied experiences gave her a command of abstract and figural drawing and of formal elements like shape, line, movement, positive/negative space, color, and texture, as the jewelry included in this retrospective attests. Her training also shaped Scherr’s attitude toward jewelry; rather than using this format to express concepts and making the wearer a vehicle for them, she sought to make beautiful, flattering jewelry that worked with the body rather than challenging it. Her many experiments with techniques and materials were always in pursuit of this goal; while she kept up with international developments in her field, she was apparently not interested in the more conceptual or iconoclastic movements in either American or European jewelry. Perhaps this is why Scherr’s work has not been widely published in contemporary scholarship on jewelry, even though her career spans the entire period of studio jewelry. All Is Possible, as an exhibition and book, correct this lack and show that her work is worth our attention.

[1] Ana Estrades, introductory text panel for exhibition and quote in Kelly McCall Branson, “Endless Possibilities: The Fearless Creativity of Mary Ann Scherr,” #creativestate, The Official Magazine of Arts NC State, Spring 2020, 34–41.

[2] STEAM is an acronym for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math, plus the Arts.

[3] Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, Makers: A History of American Studio Craft (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2009): 335–336. Scherr’s body monitors are also discussed in the new book by Susan Cummins, Damian Skinner, and Cindi Strauss, In Flux: American Jewelry and the Counterculture (Stuttgart, Germany: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2020).

[4] Evelyn McCauley, Marketing and Communications Coordinator for the Gregg Museum of Art & Design, in an e-mail to the author, January 13, 2021.

[5] Roger Manley, “Force of Nature,” in the exhibition catalog All Is Possible: Mary Ann Scherr’s Legacy in Metal (Raleigh, NC: The Gregg Museum of Art & Design, 2020): 1.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ana Estrades, “All Is Possible: Mary Ann Scherr’s Legacy in Metal,” Metalsmith vol. 40 issue 1, 2020, 46-54. Estrades’s recorded talk can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9VADzJxBcus&t=306s. Exhibition text panels can be downloaded at https://gregg.arts.ncsu.edu/exhibitions/all-is-possible/virtual-tour/.

[8] The introductory video can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yf9meTfkRbg. View the virtual tour at https://gregg.arts.ncsu.edu/exhibitions/all-is-possible/virtual-tour/. There is also a behind-the-scenes video about the mount-making at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=loC3o6xFjy4.