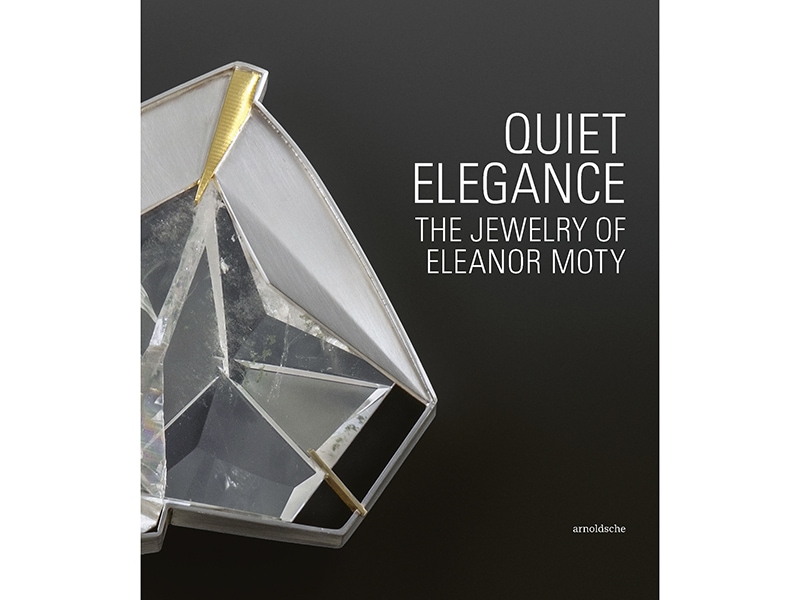

Quiet Elegance: The Jewelry of Eleanor Moty, ed. Matthew Drutt, with contributions by Bruce W. Pepich, Matthew Drutt, and Helen W. Drutt English. Stuttgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2020.

It is a well-established fact that European contemporary jewelers are better represented with beautifully designed, fully illustrated, scholarly monographs than their American counterparts, regardless of the latters’ contributions to the field. Whether or not the noted American metalsmith, author, educator, and specialist in jewelry from India and Nepal Oppi Untracht recognized this inequity, he bequeathed funds to his longtime friend and colleague, jewelry artist Eleanor Moty, so that her career could be properly documented. Quiet Elegance sets the paradigm for a monograph.[1]

This comprehensive, well-organized volume presents the voice of the pioneering Moty, whose career spans more than 50 years, with those of three illustrious curators and scholars: Bruce W. Pepich, executive director of the Racine Art Museum, who has been the force behind his institution’s significant holdings of art jewelry; Helen W. Drutt English, former gallery dealer, curatorial consultant, educator, and now grande dame of contemporary craft; and curator, scholar, and writer Matthew Drutt, acclaimed for his thoughtful, cross-disciplinary writings. In their respective chapters, the authors apply their characteristic scholarly approaches to Moty’s story.

Pepich’s essay, which appears first, traces the key moments within the development of Moty’s aesthetic. He provides in-depth stylistic analysis of works seminal to each phase of the artist’s career. Starting with a brief statement of how Moty’s formative years on a Midwestern farm established her lifelong affinity for nature and its forms, Pepich goes on to describe her groundbreaking work in photoetching and electroforming, which resulted in narrative statements composed of unfaceted stones, agates, crystals, photographic imagery, and raised, highly decorated surfaces. Moty began these wearable and nonwearable objects as an undergraduate at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, then continued during graduate studies at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, in Philadelphia, and in her early years of teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[2]

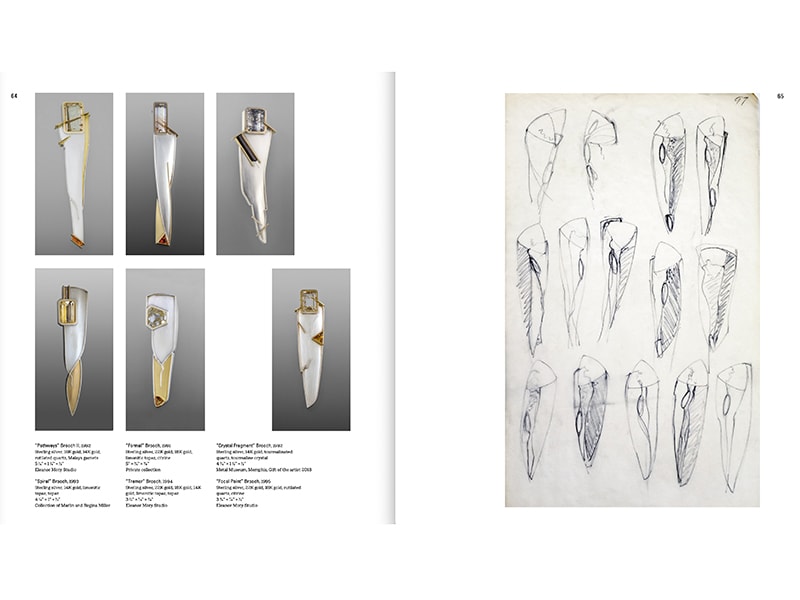

After seeing the posthumous 1976 retrospective of the work of midcentury American jewelry designer and educator Margaret DePatta, however, Moty commenced a multiyear study that led to her radically different, mature aesthetic. She moved from the earlier focus on storytelling and adopted a more formalistic approach, gradually deciding to focus on the brooch format. Inspired by DePatta’s passion for unique and unusual gems, Moty adopted her practice of using stones pre-cut by lapidary artists. After 2004, Moty used only stones cut by masters Tom Munsteiner and Dieter Lorenz.

64 x 48 x 10 mm, quartz by Tom Munsteiner, Idar Oberstein, Germany, photo courtesy of the artist

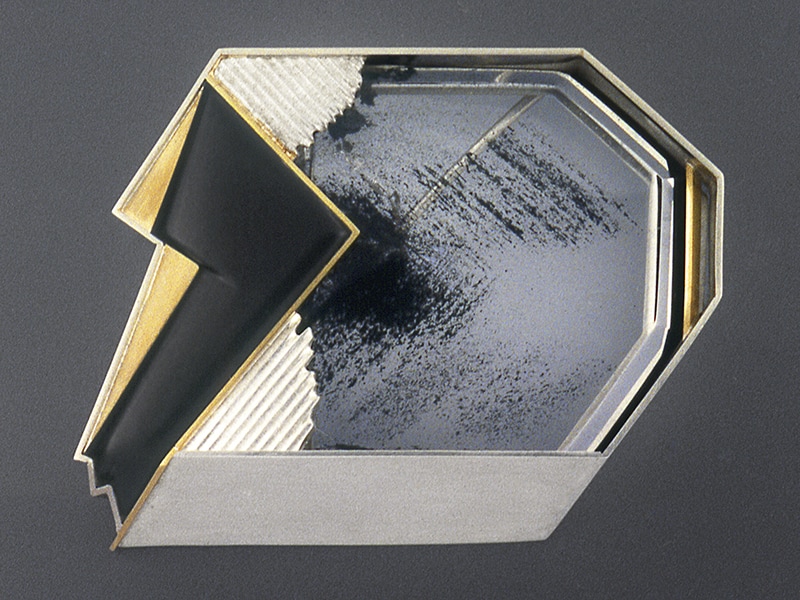

In these mature compositions, Moty juxtaposes silver and gold with carefully considered, sizable stones of rutilated (imperfect) quartz, carved agate, or other figured gemstones, so that metal and stone exert equal importance. At times, in order to enhance the attributes of the stone, she also introduces Micarta, a laminate made primarily from layers of paper adhered together by resin. Some of Moty’s most acclaimed brooches, however, are those in which the stone and metal are arranged so that light interacts with these elements to create, says Pepich, spatial effects unintentionally mimicking architectural elements such as stairs. Pepich’s careful narrative nonetheless leaves some questions unanswered. For example, the reader is perplexed by Moty’s rather abrupt decision to stop her groundbreaking work with photoetching and electroforming, since some of her best-known, innovative work employs those techniques. Only upon reading the other essays does it become clear that she was forced to do so because of their detrimental effects upon her health.

Matthew Drutt is known for his ability to contextualize contemporary craft and design within the art of the 20th and 21st centuries. His essay, “The Road Less Traveled,” examines and evaluates Moty’s contribution in multiple domains. Within the metalsmithing world, he provides important insight into the artist’s role in the formative years of the Studio Jewelry movement. In particular, he offers critical perspective on the early university metalwork programs where Moty studied and later taught, as well as on her colleagues and mentors J. Fred Woell, Fred Fenster, Stanley Lechtzin, and Albert Paley.

From the perspective of all the arts, Drutt examines Moty’s isolated efforts to incorporate photographic, hence realistic, imagery in her early work, within the context of the period’s overriding concern with image and object. He draws parallels between these solitary investigations during her student days in the late 1960s, the work of Pop artists such as Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns, and contemporary ceramicists, such as Howard Kottler, who decorated clay forms with decals of icons of popular culture, such as Blue Boy, by British painter Thomas Gainsborough.

In Drutt’s opinion, Moty distinguishes herself from her contemporaries because they are concerned with materiality or social and political commentary while she looks to the history of art for inspiration. He attributes her interest in the play of light in interior and exterior spaces to German Expressionist architects and filmmakers of the first half of the 20th century and finds that her work aligns better with that of the Hungarian-born Bauhaus instructor László Moholy-Nagy than with DePatta’s. Like Moholy-Nagy, Moty deals with the fundamentals: color, light, texture, and symmetry. Drutt concludes his thought-provoking essay by reaffirming Pepich’s contention that Moty is an “American original.”[3]

Helen W. Drutt English’s narratives often combine biographical and aesthetic descriptions with her own personal reminiscences. Her approach humanizes the artist and makes the work more accessible. In Quiet Elegance, she publishes from her extensive archive carefully chosen correspondence between herself and Moty, often annotating these materials; she also provides copious explanatory endnotes. The letters and emails provide primary-source substantiation of the observations in the two preceding essays as well as welcome insight into Moty’s personality, daily life, and enduring friendships.

It is here, in correspondence between Drutt English and Moty, for example, that the reader fully comprehends the toxicity of the materials Moty was using in her photo-etching and electroplating that led to her new aesthetic in the late 1970s and early 80s. More importantly, the posts provide windows into Moty the person: the reader begins to understand the total commitment she makes to whatever she undertakes—be it selecting cut gemstones or making sure that no lemon from the tree that she and her life partner, metalsmith Michael Croft, planted go to waste. But most telling, the reader sees the depth of Moty’s loyalty to those who have befriended and mentored her, for example her ongoing efforts to ensure that colleagues such as Woell and Fenster, who counseled and guided so many in the field, receive recognition for their labors.

Moty’s beautifully written chronology includes archival photographs and brings the publication full circle. She talks about her family and early years and then discusses her education and teaching, describing her positions and colleagues; her primary patrons; subsequent travels that impacted her aesthetic; and in more recent years, the key exhibitions in which she participated and awards she received. Although both Pepich and Drutt laud her for taking part in the early, small, regional art museum- and university-based survey shows that helped foster and promote Studio Craft, none of the authors calls out those that specifically furthered Moty’s career. Such information would have been invaluable as there is now a groundswell, as part of revisionist craft history, to recognize and celebrate regionalism.

An extensive bibliography and exhibition history round out the book. The sole disruptive element of Quiet Elegance: The Jewelry of Eleanor Moty lies in a design detail: for a reader accustomed to publications where texts are indented to indicate lengthy quotations, the indentations of alternating paragraphs may prove confusing.

The monograph is sumptuously illustrated with stunning, full-page color plates. Multiple images are arranged to show the evolution of a particular concept. One of the most laudatory features of this publication, however, is the juxtaposition of color plates of preliminary sketches with the corresponding realized designs. Pepich explains that these sketches are integral to Moty’s creative process. She would first scan a stone, then place a sheet of tracing paper over the printed scanned image and draw a design for a brooch using the scanned stone as focal point. By moving the tracing paper and repeating the process, she fills all or most of the sheet with sketches for brooches. Finally, Mary Beth Kreiner, art librarian, Cranbrook Academy of Art Library, Bloomfield Hills, MI, US, deserves special commendation for procuring the comparative literature used as the basis for this review.

Overall, Quiet Elegance: The Jewelry of Eleanor Moty is an extremely sensitive testament to the refined, sophisticated aesthetic of a kind and gracious artist.

[1] The author wishes to thank Mary Beth Kreiner, art librarian, Cranbrook Academy of Art Library, Bloomfield Hills, MI, US, for procuring the comparative literature used as the jumping off point for this review.

[2] Moty’s tenure at the University of Wisconsin–Madison lasted from 1972 until her retirement in 2001.

[3] Bruce W. Pepich, “Quiet Elegance: The Jewelry of Eleanor Moty,” in Quiet Elegance: The Jewelry of Eleanor Moty, 7.