The Fascination of Jewellery: 7000 Years of Jewellery Art at the MAKK

New permanent exhibition

Museum für Angewandte Kunst Köln, Cologne, Germany

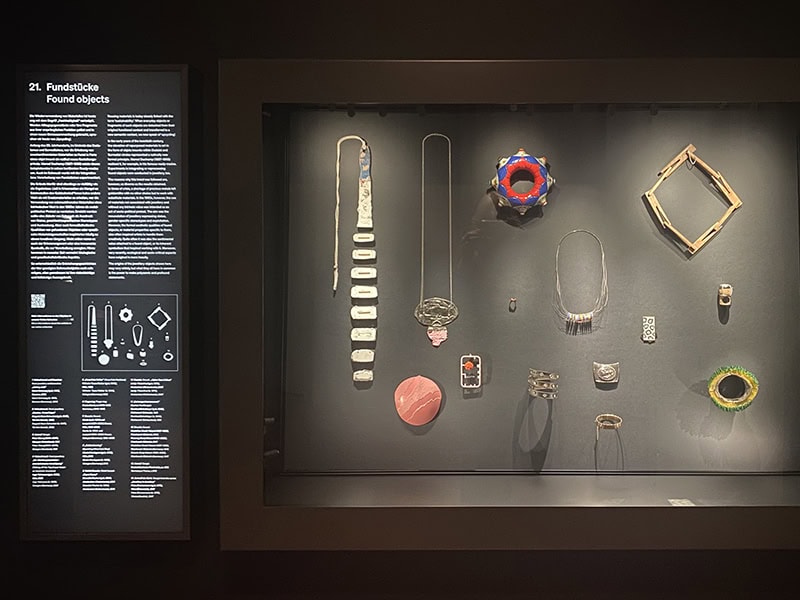

A man at a display case is laughing out loud. There’s no one else around. I probably look puzzled, so he points at a bangle made of a curtain rail and moonstones. His delight in Bernard Schobinger’s clever use of a found object makes me laugh, too. We are in The Fascination of Jewelry, the new collection presentation at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAKK) in Cologne, Germany.

![Pendant amulet, Persia?, 9th–6th century BC, in bronze, 1 ⅛ x 1 ⅛ x ⅞ inches (28.2 x 30 x 21.5 mm), donation Elisabeth Treskow, photo: MAKK / DetlefSchumacher.com. “The eyes and nostrils as well as the furrows on the [bull’s] forehead are suggested by notches,” states Lena Hoppe’s description in the catalog and online collection.](https://artjewelryforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/1_amulettanhaenger-28108-075703-800x600-1.jpg)

The show covers all the jewelry topics

Entering the jewelry room from the museum’s spacious central hall, I leave daylight behind. It takes a few seconds before I can distinguish the rows of matte-black display cases. The curators, museum director Petra Hesse and researcher Lena Hoppe, have organized this exhibition as a mix of chronological displays and subject matter that span epochs. Almost all the jewelry topics are covered, including memento, nature, identity, gender, and luxury for the masses.

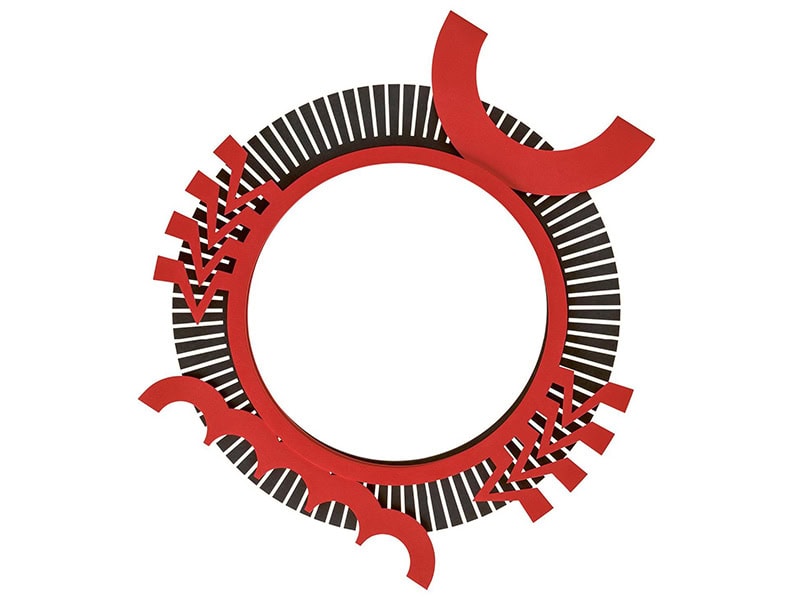

The 28 different themes make for the perfect lesson in jewelry history. A display about functionality holds an ancient belt buckle, a strap end,[2] and a pomander. Another, about dimensions, shows two very rigid torques by David Watkins and Wendy Ramshaw. All 370 pieces are presented as in a treasure trove, shimmering in small puddles of light. Even Watkins’s large, machine-cut plastic piece from the 1980s.

In the textbook list of topics, the interests of some local personalities bring in extra color. There are, for example, the antique carved gemstones donated by the artist and first female art teacher in Cologne, Elisabeth Treskow. We owe a display case with old and new granulation work to her study of Etruscan techniques. And the remarkable 19th-century parures, or sets of matching jewelry, were the personal obsession of another big museum benefactor.

Piecing together the information

Each of the thematic displays has an introductory text. I wish they were less general and mentioned the examples on view. The works themselves are labeled only with a year, the maker, and—very important somehow—always the place of creation. But even the display about material experiments doesn’t mention materials.

A tiny amulet catches my eye. It comes from Persia, but what is this unfamiliar shape? Pointing the phone at the QR code on the glass case not only resolves the question (it is a stylized bull’s head cast in bronze) but also opens a wealth of online descriptions by curators Hesse and Hoppe that are well worth reading!

At the display case about “Jewellery & identity,” for example, the introduction warms the visitor to the idea that jewelry can give nonverbal clues about one’s cultural identity. But how? Following the QR code for Nhật-Vũ Dang’s neckpiece from the series Where the Hell Are My Keys? reveals that the engraved pottery shards underline how the artist is torn between two countries that happen to have a ceramics tradition, the Netherlands and Vietnam.

Was I going to unlock these treasures 370 times? No. Then I found the accompanying catalog[3] in the room and saw that all those texts were in it! I used the book instead of my phone.

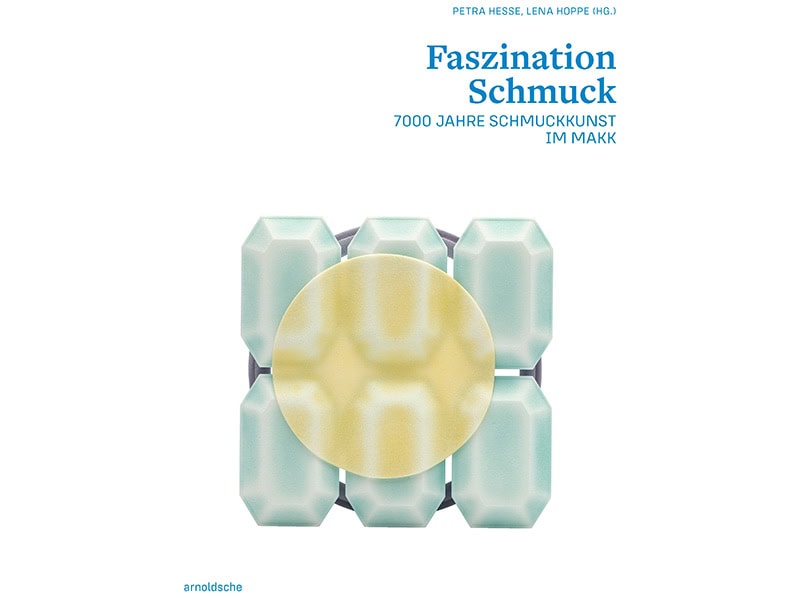

A bright book

The catalog documents the exhibition exactly. The texts are identical, including the somewhat stiff choices in the English translation, with words such as polysemic, conjecture, and concomitantly (AJF’s editor, a native English speaker, is herself unfamiliar with some of this vocabulary). Every one of the 370 pieces in the exhibition is pictured in the book, grouped under the same themes. The knowledge that I won’t miss anything gives me a sense of serenity. Unlike the dimly lit museum gallery, this book is clear and bright. I can now see the mini mosaic in a larger-than-life image of a neoclassical brooch.

This book is also one of the official catalogs of the museum’s collection, as the catalogs Schmuck I and II were in 1985.[4] Hesse and Hoppe invited one of the authors of those books, Beatriz Chadour-Sampson, to contribute to the new tome. First, she outlines the history of the collection based on a couple of major donations. But she wastes no time in taking the reader on a lightning-fast flight through European jewelry history. She uses the pieces she knew so well as stepping stones, but doesn’t discuss the more recent additions very much. In the last part, Chadour-Sampson compares several museums with jewelry of this caliber. Some concentrate on an era, others on a type, such as rings. Her conclusion is that the MAKK is exceptional in showing an entire history of jewelry at once, something that can only be seen at the V&A, in London, the Schmuckmuseum, in Pforzheim, and the MFA, Boston.

Strategic collecting

Leafing through this catalog, I learn about the “profile” of the MAKK collection and its focus on Europe. The museum has the intention to represent more women makers. Another aim is to show how modern and contemporary jewelry reflects concerns about sustainability and harmfully sourced materials. In the exhibition itself, this theme is not overly present. But there is a 1977 necklace by Peter Skubic in stainless steel instead of gold. It serves as an early example of social and political critique expressed in jewelry that protests Apartheid in gold-producing South Africa.

Big crowds

I often find that museum jewelry rooms don’t draw many visitors. In Cologne there were lots of people when I visited, two months after the opening, both on a night with reduced ticket prices but also on a regular weekday. From their conversations, these were not jewelry insiders. The museum hasn’t yet determined what’s the draw: the historic jewelry or the contemporary pieces.

Although Cologne no longer has an art school with a jewelry department, quite a few people remember the days when Elisabeth Treskow and her contemporaries were active in the city, so the local history could be what’s bringing in attendees. What can be measured, says curator Hoppe, is that since the opening, in December 2024, the museum has seen visitor numbers rise. Mission accomplished! Hesse and Hoppe have plans to keep interest in the jewelry collection keen by creating small, themed exhibitions in the main room. After all, only a small portion of their 1,700-piece collection is now on view. Temporary exhibitions in another part of the building complement this ambition. Already, From Louise Bourgeois to Yoko Ono, a show about female artists who also designed jewelry, is scheduled for fall 2025, with loans from Paris.[5]

DetlefSchumacher.com

I am happy to see a new place on the jewelry map. The MAKK has taken the leap to make jewelry a focal point. The Fascination of Jewellery is solid and reliable, and a perfect exhibition to take students to.

More information

See the jewelry that the MAKK has online here.

Reviews are the opinions of the authors alone, and do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] See them here. The museum’s page for this exhibition is here.

[2] A protective and often decorative metal casing at the free end of belts, etc.

[3] It’s published by Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

[4] The MAKK published thematic catalogs of their collection, beginning in 1963 with a volume on glass, then stoneware, majolica, porcelain, and so on. The tenth volume, on jewelry (Schmuck), was too large and was split into Schmuck I, with 600 pages on neck, ear, arm, and garment jewelry, and the 350-page Schmuck II, on finger rings. The authors were Anna Beatriz Chadour and Rüdiger Joppien. Schmuck I and Schmuck II were the first books on jewelry from antiquity to the present in the German language. The double volume was published in 1985, parallel to the last exhibition at the museum’s former location, the Overstolzenhaus.