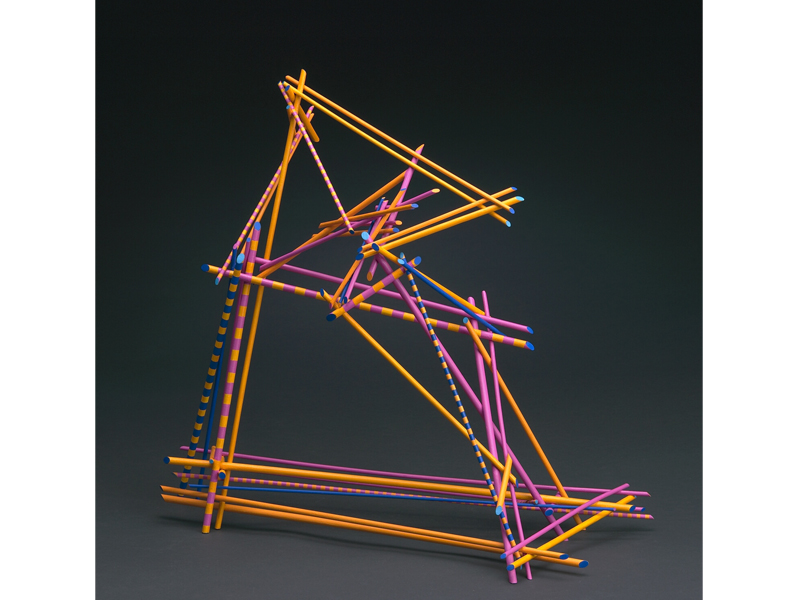

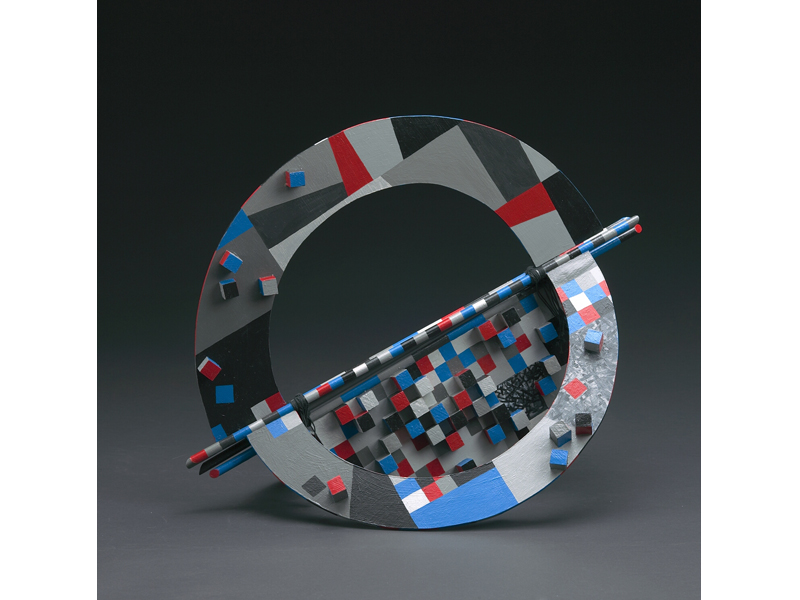

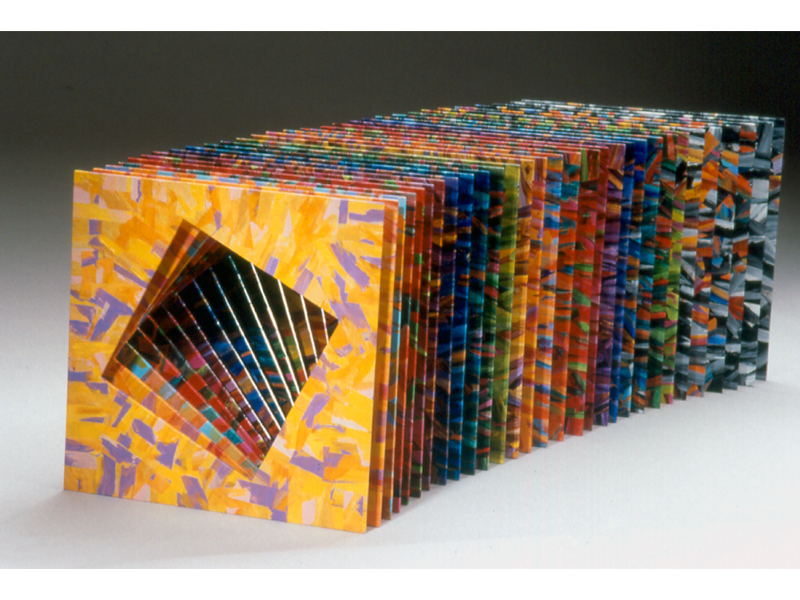

Gaudy. Oversized. Humorous. “So American.” Marjorie Schick has been making louder work than anyone else in the field for the last 55 years. She also worked with performance as early as 1977, and tested the idea of integrating wearable elements into static, sculptural objects before everyone else, while also flirting with the vernacular of fashion. Today, she stands as a model of fearlessness for a younger generation of jewelers interested in the radical scale and colors of her work. Matt Lambert, another maker with a penchant for the extra-large and the bold, asked her about boundaries, her interest in art, and her future plans.

Matt Lambert: Let’s begin this interview with how you got started. When and how did you discover jewelry?

Marjorie Schick: Having grown up dreaming of becoming a Hollywood costume designer, I filled boxes full of paper doll clothes for Brenda Starr and other career women in the funny pages, and imagined myself wearing the rings I saw in the local jewelry store. I loved jewelry and still have jewelry pieces from childhood. As a teenager I enjoyed the fashion design and illustration classes for high school students at the Chicago Art Institute.

By college I had cast these dreams aside, instead wanting to be an art teacher like my mother. At the University of Wisconsin I took several jewelry classes with Arthur Vierthaler. I met James Schick at UW and we planned to marry after he completed his master’s in history and I got my bachelor’s in art education. Jim applied for the doctoral program at Indiana University (in-state tuition), and I decided to go for an advanced degree. But in what area of concentration? I had no idea. Having watched me for four years at UW, Jim thought I liked jewelry best, so I put the checkmark there. He chose my future!

IU accepted me. Barely. “Your work is very ordinary but we will accept you anyway.” Looking back, I’ve spent my career proving they made the right decision. Obviously I needed further study. The incredible Alma Eikerman, IU’s peerless jewelry and silversmithing professor, was my mentor and teacher. She gave me direction, focus, and freedom. Her sculptural approach was as new to me as was forging metal. In fact, just about everything she taught me was new. She inspired me as a person and as an artist, imparting aesthetics, design skills, self-discipline, and life lessons, while asking nothing of her students that she did not require of herself. She provided the foundation for what I became. Two decades after her death, I still work for Alma.

When I first approached you about doing this interview, you responded by saying that the topic of large bodywork is timely. Could you explain why you think it’s an important topic in jewelry at this time?

Marjorie Schick: You can see an intense and lively interest in all forms of body decoration everywhere, from tattoos and body painting to sculptural clothing. Jewelry exhibitions, including SNAG’s Jewelry in Motion, now include large bodyworks. The ever-growing Australian Body Art Festival in Queensland has significant Internet coverage. Two of the many museum shows recently featuring art for the body are the Mint Museum’s Body Embellishment and the High Museum showcasing Dutch artist Iris Van Herpen: Transforming Fashion. Among other exciting bodyworks are Nick Cave’s Sound Suits and Jum Nakao’s paper couture. Sculptural body pieces and large-scale work are now getting their respect. Red carpets and award shows and fashion magazines document this influence. Jewelry, sculpture, and fashion are bound together in the way I understand what I’m doing, and increasingly how others approach their work.

You are often cited as being inspired by the sculptor David Smith. What is it about his work that inspires you?

Marjorie Schick: In David Smith’s forms, I experience boldness, definitions of space, surfaces, and structures. I admire his work ethic and his questions for students. In 1966, while preparing for my final IU graduate review, I pored over a publication featuring his work and thought how exciting it would be to extend your arm or head through a hole in the sculpture. By becoming part of it, you could experience the sculpture and space in a new way. Greater intimacy occurs when wearing the sculpture than viewing it on a pedestal. That was when I knew that I wanted to create sculptures to wear.

I’ve been designing pieces that will stand alone or devising mountings for my work to exhibit them when not being worn. They exist as sculptures, completing my circle.

Your work is strikingly colorful and has many parallels to the vernacular of costume as well as carnival and cultural dress. Are any of these relations conscious for you when you are approaching your work?

Marjorie Schick: Only cultural forms of body adornment, especially African because of the forms, their size, and the choice to wear multiple pieces.

In the early 1950s, my art-teacher mother’s colleague, Cay Wells, gave me two things: a totally hand-stitched jacket and an article about Bernard Rudofsky from a 1946 issue of Life Magazine. I was amazed that so much could be done by hand; the jacket showed me that one could do anything one set one’s mind to do. The Rudofsky article, “The Human Look: A Designer Finds Fashions Ruin It,” had an even more profound effect on me by initiating my deeper fascination with body decoration. Rudofsky illustrated parallels between cultural and historical fashion, such as bound Chinese feet next to contemporary high heels and African stacked brass neck rings beside a contemporary choker. I have always been inspired by the ways we can connect with other cultures and how we can discover inspiration in the creativity of societies and times quite different from our own.

In 1955, as a freshman in high school, I saw a Design Quarterly issue (# 33) from the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis covering its 3rd Annual Exhibition of Contemporary Jewelry, including work by Harry Bertoia, Margaret De Patta, Sam Kramer, Philip Fike, and others. I think that had an influence greater than I knew then. Inspiration may work immediately or take years to bubble up to impact your art.

Your work is aggressive and bold. Does scale explain that? Toward what or where is this aggression directed?

Marjorie Schick: Large bodywork isn’t necessarily aggressive by virtue of its scale. Arline Fisch and Flora Book have both built forms that cover a large part of the body yet flow gracefully and elegantly when it moves. Aggression in one’s work comes more from the nature of the shapes, possibly the colors, and even the materials, as well as the intent.

I want my work to affect both the wearer and the viewer. This boldness requires the wearer of a large piece to relearn how to move and experience space. Making my work aggressive is about jarring someone in terms of ideas about wearing large-scaled art, or giving an aesthetic jolt of how the work appears on the body and works with or against it. If there is aggression in my work, it is manifested in providing an awakening about wearable art.

Perception may influence this assumption of aggression. Several jewelers have commented that they assumed a man was responsible for my work because it is difficult to wear. As one man said, my work was so “powerful” he imagined only a man could do it. These people interpreted my work as aggressive and then translated that into how a man would approach art that decorates the body. But, you see, I do not classify what I do as decorative art for the body. Yes, it may decorate and the body is where it belongs, but that isn’t what I’m trying to do when I make a piece. It is art that can and should be worn but can also function independently of the body. My work isn’t supposed to be stored in a jewelry box or in a drawer but out in the open, on the wall, somewhere that it exists 24/7/365, not just when it’s worn.

How does making work for the body and the wall affect your choices?

Marjorie Schick: I most often start with an idea and then work directly with the material, making decisions throughout the building and painting processes but not usually making sketches before starting to work. As the form grows, I assess it on myself or ask someone to model it. I also view the form off the body from all angles on a table or the wall, and study it at a distance as well as up close. Occasionally I make sketches during the creation of a piece to help solve specific problems I may have with it and to figure out a variety of solutions on paper. With Vierthaler, I drew to design the finished piece. Eikerman stressed drawing for artistic skills and idea development, but I don’t recall making detailed drawings of what I would make, only idea sketches after the drawing assignments.

I had a colleague who once remarked that I expect too much from my pieces because I want them to work aesthetically from the front, the back, upside down, and sideways, plus on the body, off the body, on the wall, and/or on the pedestal, and even to stand up by themselves. I do. This comes directly from Alma and continues to drive me today. As sculpture, it’s got to be viewable from every angle.

Eikerman insisted we make the backs of our pieces as finished and as considered as the fronts. Further, the thickness or thinness of our hammered metal edges was equally important, and the piece had to have the correct weight physically for its appearance. Today, even though I use wood or papier-mâché, I spend much time working the edges, sometimes building them up and always filing and sanding them to what I hope are the correct angles. It’s exciting to make a piece both wearable and a sculpture that works from all points of view.

Do you want to install your own work? Does the display become part of the piece? Does this display remain constant, or do you change it in different settings?

Marjorie Schick: I want to be there for the hanging. And at the dismounting, to ensure its preservation.

I like the challenges of installation. I learn new approaches from the gallery staff. The dancers who in the 70s used my pieces as props taught me much about my own work I hadn’t previously recognized, and I think it’s the same about putting pieces into different spaces. It is sometimes necessary to explain which way a piece goes, and how I envision it being worn. Display matters to me aesthetically, for the drama it can create, and for the manner in which it is able to draw viewers into my work.

If I cannot be present and the installation of the work is complicated or can be done just one way, I include photos or written suggestions with the artwork to illustrate how I would prefer it to be displayed; otherwise I leave it to the discretion of the gallery preparators, knowing that the work will appear differently in each new setting. As it should.

You intend your work “to question the traditional boundaries of jewelry.” Which ones?

Marjorie Schick: My work not only brings the wearer and the viewer to question what constitutes jewelry, but also how the wearer navigates life’s spaces and what adornment truly means. I am encouraging a reconsideration of what materials are suitable for jewelry, as well. In the past, of course, precious metals and stones were prevalent—though societies have defined precious variously—but I use materials that aren’t precious: paper, wood, wire, canvas, and paint.

To me, alternative or nontraditional materials can be elevated through intent, form, and craftsmanship.

What boundaries do you see in jewelry today? Are these boundaries created by an outside market pushing in, or are these limits determined by the maker?

Marjorie Schick: Because I have been a salaried college professor, I haven’t had the financial burden of earning my living by pleasing customers. I make art that pleases me. If it sells to someone who will value it as art, or it goes to a museum, I am content.

In my early work, I had to break through working with papier-mâché and working large, but also had to break through my own boundaries.

When I began making papier-mâché in the late 1960s, I continued making metal pieces. The latter was my “serious” art; the other I felt compelled to do but wasn’t sure that it was as important. It took years before I stopped making that distinction and considered my “other” work of nontraditional materials as equally serious.

I cannot imagine any artist self-consciously producing art who doesn’t think of the work surpassing boundaries.

Let me add another dimension. Years ago, European jeweler friends remarked that my work was “so American” or I was “so American” as an artist. What I believe they meant is that I felt free—or considered myself free—to do whatever I set my mind to doing. In materials. In choosing my market. In scale. In purpose. They seemed to feel constraints far more than I have, or at least that’s the impression they conveyed. These limits are not only needing to satisfy a market, but also in terms of getting a professional degree, the tests they must undergo, the classes they must take, and the standard they must achieve to function as a recognized artist. So I would add cultural boundaries I have not felt, but that others might see me breaking.

What do you tell someone who isn’t familiar with your art what you do?

Marjorie Schick: I build body sculptures and large-scaled jewelry of painted wood and papier-mâché. The questions usually stop then. I should carry pictures of my work to help explain it. Not long ago, Jim and I met with a business professional who asked what I do, so Jim suggested that he look me up on the Internet. When we saw him the next day, he said he was very surprised by my art, that it was not what he expected. Because my voice is soft and my manner mild, only my multicolored hair hints that I might be an artist. Then they see what I’ve done and goggle! Perhaps this also goes back to that aggression question. I am not aggressive. For whatever reason, not just as I create it but as others perceive it, my work can be very aggressive. I am not unhappy about that!

As jewelry blurs the lines between art, fashion, and design, where do you see large avant-garde work finding its place? Does larger work have a stronger potential to break outside of the jewelry gallery and further challenge what jewelry is or can be in other settings?

Marjorie Schick: Though there may not have been a niche for these works in the past, the current state of flux and change and boundlessness may be creating one. Consider Coiled Corset, the collaborative work of Alexander McQueen and jeweler Shaun Leane that straddles fashion, jewelry, and art. Look at Iris Van Herpen’s “dress” made of the ribs of hundreds of children’s umbrella frames. Is it a dress, a sculpture, body jewelry? Definitely it is art and wearable. This is an enormously exciting time right now because there are so many imaginative and creative forms being made. It is harder that there is not a special area just for large-scaled work but, on the other hand, it is exciting that it is included in jewelry shows, in art shows, and is being more and more accepted.

What do you tell students and beginning makers who express a desire to make large work but fear finding a market or niche for their work?

Marjorie Schick: I remember a year when I was rejected from eight shows and had maybe just three acceptances. For years my work failed to make it into some regional art shows, even after I had begun to exhibit internationally. Rejection seems to come with the territory no matter the form of the art, painting, sculpture, or jewelry. Perhaps it’s a matter of those boundaries discussed earlier, for the boundaries are not always of your own making.

The best advice is to have confidence in what you are doing, believe in it, and keep doing it. No matter what obstacles are put in your path. Of course it’s easy to lose confidence. This is so in professional sports and, I imagine, in most fields of endeavor. Don’t lose heart. Rededicate yourself to your vision. Persist. Resist the naysayers you meet and the ones inside your head.

It may not be easy to find a market or a niche but keep searching, because they do exist.

My work has caused me storage problems and also shipping difficulties, so I usually laugh and tell myself to “keep it small” (and seldom follow that advice!), but the serious part of the answer is that students must follow their hearts, do what they believe in, and not get discouraged if they are bucking the trends. Have confidence in your work and do what you feel is right.

What is now inspiring or fueling you as a maker? What are your current sources of inspiration?

Marjorie Schick: It is a crazy answer, but my new inspiration is aluminum armature wire. It is soft enough to form with my hands (perhaps too soft) but it can outline, thicken an edge, and add strength.

I am working on a pair of huge spiral canvas armlets (457 mm in diameter) on which I have stitched armature wire around the edges. The wire is soft enough to allow for the opening of the spirals to run up the arms from the wrists to the shoulders but can be collapsed to be flat again. I want to do a spiral canvas collar in the same manner so it will open in various ways down around the shoulders and arms when worn, but go back flat for display or shipping.

Presently, my favorite jewelry book is Norman Cherry’s Jewellery Design and Development from Concept to Object. It focuses on the development of ideas of 17 jewelry artists and follows their concepts through to finished pieces. The differences in the approaches of each of the artists covered is thoroughly fascinating and inspiring.

What is currently on your work table? What new projects on the horizon?

Marjorie Schick: I am currently working on bracelets that are studies in curving planes and edges for the forthcoming group color show curated by Gail M. Brown at the Tansey Contemporary art gallery in Santa Fe.

I want to get back to work on the series of wood shirts I have started—each with a detachable, wearable part such as a necktie. One, for Calder, will make reference to a pullover sweater over a shirt and perhaps have a detachable mobile brooch. The Jim Dine one references a robe instead of a sweater, with a detachable handkerchief in the pocket, and the Max Bill one will have a geometrical, clean-cut shirt with a tie. Antoni Gaudí and Niki de Saint Phalle are two others in the series.

The multiple wood parts for these are cut but not assembled nor painted. Because I have had smart and talented assistants helping me with my work, I now have enough pieces started to keep me going for years.

I have also been painting a large wearable that is made of wood with canvas between the sections that allows for movement. In fact, the piece can be collapsed and can stand up or be opened out to be flat. It is to be worn diagonally across the body as a bandolier.

For Munich’s 2016 Schmuck, I sent three recent pieces and another three for Galerie Ra’s presentations at Frame.

My only problem now is finding time. Among other things, I must divert myself for teaching (I teach online now, and 2016–2017 will be my last year of teaching, my 50th as a college professor at Pittsburg State University in Kansas—after a year at the University of Kansas); for answering questions from students (often from the UK, as my work has appeared in the Design Studies section of the Scottish N5 National Qualifications exam, the Victorian Certificate of Education exam, and the WFH Art and Design exam); and for the day-to-day business of living.

Thank you!